注:本文为 “数学学习 | 数学实践能力提升” 相关合辑。

英文引文,机翻未校。

中文引文,重排未校。

如有内容异常,请看原文。

What are good “math habits” that have improved your mathematical practice?

有哪些好的 “数学习惯” 能提升你的数学实践能力?

Ask Question

I currently feel like I am not doing maths the best way I could; that is, I’m not making the most out of my time when I’m working on maths problems.

我目前觉得我没有用最好的方式做数学,也就是说,我在解决数学问题时没有充分利用时间。

The main thing I feel is that I’m not organizing my mind and my derivations as clear as I could, because I don’t have the best “math habits.” I feel like if I could develop better math habits, I could significantly improve both my time efficiency and the quality of my thinking.

我主要觉得我没有把思路和推导过程整理得足够清晰,因为我没有最好的 “数学习惯”。我觉得如果我能养成更好的数学习惯,我能显著提升我的时间效率和思考质量。

以写作技能类比自身数学困境

To show what I mean, I’ll compare it with the skill of writing: I used to write in a very unstructured way: I simply started writing with some vague idea of what I wanted to write. Then after having written a paragraph, I would generally be somewhat confused. After 2 paragraphs I’d be more confused. Eventually I didn’t have a clear idea of what to write because my mind was so cluttered, as if all my neural pathways were firing un-synchronously, creating a senseless mess. I have now solved this by developing better habits: I started making bullet point lists of my papers that contained the central argument, before I wrote the actual paragraphs. I then wrote one paragraph at a time, focusing only on what that particular one had to convey. Also, I developed a more structured way of structuring paragraphs: rather than just “writing it,” I thought about the first sentence separately, and then its relation to the second, and so on… After developing these better habits, I felt like my brain had a much more “lean” and “uncluttered” process it was following, as if my neural pathways fired synchronously, in harmony.

为了说明我的意思,我将其与写作技能作对比:我以前写作的方式很不系统,我只是带着一些模糊的想法开始写。写完一段后,我通常会有些困惑。写完两段后,我会更困惑。最终,我没了清晰的写作思路,因为我的大脑一片混乱,好像所有的神经通路都在不同步地工作,制造出一堆毫无意义的混乱。我现在通过养成更好的习惯解决了这个问题:我开始在写实际段落之前,先列出包含中心论点的要点清单。然后我一次只写一段,只关注那一段要传达的内容。此外,我还发展了一种更有条理的段落结构方式:不是简单地 “写出来”,而是先单独思考第一句话,然后思考它与第二句话的关系,以此类推…… 在养成了这些更好的习惯之后,我觉得我的大脑遵循了一个更 “精简” 和 “不混乱” 的过程,好像我的神经通路同步、和谐地工作了。

数学学习中的具体困扰

I feel like right now with maths, I am in a similar stage that I used to be with writing. I understand math concepts, and I know how to do many of the methods, and I’m progressing. But whenever I’m working on a math problem, I feel like I’m getting confused, not just because the problem is new and difficult, but because my mind is cluttering and confusing itself, as if I don’t have a “process” that is optimized for figuring out new math.

我觉得现在我在数学方面处于以前写作时类似的阶段。我理解数学概念,我知道很多方法怎么做,我也有进步。但每当我解决数学问题时,我感到困惑,不仅是因为问题新颖且困难,还因为我的大脑在自己制造混乱,好像我没有一个为解决新数学问题而优化的 “流程”。

One way this shows, though I don’t know if its a cause or a symptom, is that my derivations look like a plate of spaghetti. Yet if I try to write things more structuredly, I’m held back even more, because it puts me into a very “fearful” and paralyzed state of mind (fearful to write something wrong).

这种现象的一个表现是,我的推导过程看起来像一盘意大利面。然而,如果我尝试更有条理地写东西,我会更加受阻,因为它让我进入一种非常 “恐惧” 和僵化的思维状态(害怕写错东西)。

求助方向与补充说明

So I’m looking for habits that I can develop that will, just like I did with my writing process, turn my “cluttered” mind, into a “harmonic” one. That doesn’t mean math will suddenly be easy, but at least the difficulty will be due to the complexity of the math, rather than due to me working against myself.

所以,我在寻找可以养成的习惯,就像我改进写作流程那样,把我的 “混乱” 大脑变成 “和谐” 的大脑。这并不意味着数学会突然变得容易,但至少困难将源于数学本身的复杂性,而不是因为我自己在和自己作对。

So I’m interested if any of you have experienced this same thing, and whether there have been specific habits or other things that have helped you overcome this.

所以,我想知道你们中是否有人有过同样的经历,以及是否有特定的习惯或其他东西帮助你克服了这个问题。

自身尝试的有效方法举例

To give an example of something that recently has actually helped me somewhat: Whenever I now derive an intermediate result, I write big boxes around it, with a big dense filled circle in the corner, in order to signify that it is an important result. This somewhat declutters my mind, because I no longer have to wade through all the intermediate steps, looking for the important stuff.

举个最近确实帮到我一些的例子:每当我现在推导出一个中间结果,我就会在它周围画一个大框,在角落画一个大的实心圆圈,以表明这是一个重要结果。这在一定程度上清理了我的大脑,因为我不用再在所有中间步骤中寻找重要的东西了。

问题合理性说明

ps. I hope this question is not too general or subjective. I know that subjective questions are not the purpose of math.stackexchange, but I thought: there certainly are some objective principles behind what kind of habits work and don’t work. And I wouldn’t be surprised if I’m not the only one who could benefit.

附:我希望这个问题不要太笼统或主观。我知道主观问题并非数学问答网站(math.stackexchange)的定位,但我认为:决定什么样的习惯有效、什么样的习惯无效,背后肯定存在一些客观原则。而且,若不止我一人能从中受益,我也不会感到惊讶。

补充提问(推导过程组织方式)

Here is a suggestion: There is a certain topic that the answers haven’t addressed, so maybe someone can address this with another answer:

这里有一个建议:有部分话题尚未在已有回答中涉及,或许有人可以补充回答:

How, in a very practical sense, do you write down your derivations, and how do they help make you more effective?

从非常实际的角度来说,你是如何写下你的推导过程的?这些方式又如何帮助你提升效率?

-

For example, do you have two separate pieces of paper for intermediate results and for details?

例如,你是否用两张分开的纸分别记录中间结果和细节步骤? -

Are there any specific ways of organizing your derivations on paper, or in notebooks, that help clear your mind?

是否有特定的方式,能在纸上或笔记本中组织推导过程,从而帮助理清思路? -

Do you write everything linearly, from top to bottom of your notebook, or do you go back and forth on your scrap paper, only writing it linearly when you’ve found the result?

你是从笔记本顶部到底部线性地记录所有内容,还是在草稿纸上反复修改,直到得出结果后才线性整理? -

Do you scratch formulae completely if you’ve made a mistake, and start over, or do you just correct the formulae?

若出现错误,你会将公式完全划掉重新开始,还是仅修正错误部分? -

Do you write derivations quickly on a scratchbook, until you’ve found the final answer, or do you write them neatly from start to finish?

你是在草稿本上快速记录推导过程,直到得出最终答案,还是从头到尾都工整书写?

提问者

edited Sep 14, 2021 at 11:16

asked Apr 16, 2017 at 18:57

user56834

评论

1.rah4927(Apr 16, 2017 at 19:10)

I have a friend who’s good at non-enumerative combi (similar to competitive programming problems). He’s good at organizing data efficiently. He is pretty smart at experimenting with processes - for example, drawing trees, graphs, tables etc. to get some intuition about a problem. And one thing that sets him apart is that he never misses “easy” things that disorganized people miss.

我有一个朋友擅长非计数组合(类似于编程竞赛问题)。他擅长高效地组织数据,在通过流程实验理解问题方面很有技巧 —— 比如画树形图、图表、表格等,以此建立对问题的直觉。他与众不同的一点是,从不会像缺乏条理的人那样,遗漏那些 “简单” 的关键信息。

2.user56834(Apr 16, 2017 at 19:21,回复 rah4927)

@rah4927, that sounds good. Could you elaborate on what it is exactly that he does that allows him to “not miss easy things”? Maybe he can give an answer to the question if he has an account :

@rah4927,这听起来很有启发。你能详细说说他具体做了什么,才做到 “不遗漏简单关键信息” 吗?

3.DVD(Apr 19, 2017 at 22:25)

Put the date on your notes, check your answers by plugging them back…

在笔记上标注日期,通过代入结果来验证答案……

4.ryang(May 15, 2022 at 12:31)

Thanks for asking this Question; every single Answer thus far is excellent!

感谢你提出这个问题,迄今为止的每一个回答都非常出色!

回答部分(9 Answers)

回答 1:levap(Apr 16, 2017 at 21:58,+50)

I think this is a great question and you’ve already made an important step in addressing the problem - realizing that you are not satisfied with your math working process and searching for ways to improve it. Here are some ideas and suggestions which I found helpful:

我认为这是一个很棒的问题,而且你已经迈出了解决问题的重要一步 —— 意识到自己对当前的数学学习流程不满意,并主动寻找改进方法。以下是一些我认为有帮助的思路和建议:

1.深入理解核心研究对象(Understand well the basic objects of the game)

This means that you should be able to give many interesting examples and non-examples of the objects you work on. Make a (mental or physical) list of such examples. What are the most important examples of vector spaces? Of subspaces? Can you give an example of something which is not a subspace? What kind of constructions generate subspaces? What kind of integrable functions are there? What do you know about them? And so on.

这意味着你需要能举出所研究对象的多个典型例子和 “反例”,可以在脑海中梳理或在纸上列出这些例子。例如:向量空间的核心例子有哪些?子空间呢?能否举出一个 “非子空间” 的例子?哪些构造方式能生成子空间?可积函数包含哪些类型?你对它们的性质有哪些了解?诸如此类。

2.先吃透问题表述,再着手解决(Make sure you understand everything about the statement of the problem first)

If you don’t, go back and review what you have learned. There is no point in trying to solve an exercise about nilpotent linear operators if you can’t give an example of a nilpotent operator and an example of a non-nilpotent operator. This will only cause you to halt and feel depressed.

若对问题表述有疑问,先回头复习相关知识。比如,若你连幂零线性算子的 “例子” 和 “非例子” 都举不出,试图解决这类习题就毫无意义,只会让你停滞不前、感到挫败。

3.借助简化模型突破困境(Play with simplified models)

This is something I really learned in graduate school and I wish I would have been told explicitly much earlier. If you are facing a problem that you have no idea how to approach and you feel paralyzed, try to work on a simplified (even trivial) model. For example, let’s say you need to prove some statement about a linear map

T

T

T on some vector space

V

V

V and you have no idea what to do. Can you solve the problem if you assume in addition that

V

V

V is one-dimensional? Even better, if

V

V

V is zero-dimensional? Can you do it if

T

T

T is diagonalizable? If you are asked to prove something about a continuous function, can you do it if the function is a particularly simple one? Say a constant one? Or a linear one? Or a polynomial? Or maybe you can do it if you assume in addition it is differentiable?

这是我在研究生院真正学到的方法,真希望能更早有人明确告诉我。当你面对问题无从下手、陷入僵局时,尝试从简化模型(甚至是极简单的模型)入手。例如:若需证明向量空间

V

V

V 上线性映射

T

T

T 的某个性质,却毫无思路,不妨假设

V

V

V 是一维的 —— 能解决吗?再极端些,假设

V

V

V 是零维的呢?若

T

T

T 是可对角化的,又能否推导?若问题涉及连续函数,假设函数是简单的常数函数、线性函数或多项式函数,能否证明结论?再或假设函数可导,是否能找到突破口?

Applying this idea has two advantages. First, more often than not you’ll actually manage to solve the simplified problem (and if not, try to simplify even more!). This will increase your self-confidence and help you feel better so that you won’t give up early on the harder problem. In addition, the solution of the simplified problem will often give you some hints on how to tackle the general one. You might be able to perform an induction argument, or identify which properties you needed to use and then realize those properties actually apply in a more general context, etc.

这种方法有两个好处:一是你大多能解决简化后的问题(若仍不能,就进一步简化),这能增强信心,避免在难题上早早放弃;二是简化问题的解法往往能为解决一般问题提供线索 —— 你可能会发现可通过数学归纳法推广,或识别出关键性质并意识到其在更一般场景下仍适用等。

4.通过 “去掉假设” 定位关键性质(Drop an assumption to identify crucial properties)

When working on a problem, try to drop an assumption and see what goes wrong. Often this will help you to identify the crucial property which you need to actually solve the exercise and then you can review the theorems and results you learned to see if it actually holds.

解决问题时,尝试去掉一个前提假设,观察会出现什么矛盾。这通常能帮你定位到解决问题所需的 “关键性质”,之后再回顾所学定理,验证该性质是否成立。

5.为核心概念建立 “心理图像”(Associate mental images with key concepts)

Try to have some mental image associated to any important object and concept you meet. This way, when you’ll work on a problem which involves various objects and concepts, you’ll already feel familiar with them and won’t halt and feel paralyzed. Review the images as you make progress and make adjustments as necessary. For example, for the notion of a direct sum decomposition you can hold in your head the image of

R

3

\mathbb {R}^3

R3 decomposed as the “sum” of the

x

y

xy

xy-plane and the

z

z

z-axis. This is, of course, a particular example of a direct sum decomposition but it helps you to feel much more at ease with the concept.

为每个重要的数学对象和概念建立 “心理图像”。这样,当遇到涉及这些概念的问题时,你会因熟悉感而避免陷入僵局。随着学习深入,可不断修正和完善这些图像。例如,理解 “直和分解” 时,可在脑海中构建

R

3

\mathbb {R}^3

R3 分解为

x

y

xy

xy 平面与

z

z

z 轴 “之和” 的图像 —— 虽这只是直和分解的一个特例,却能让你对该概念更易理解。

6.构建概念与结论的关联图(Build a map of relations between concepts and results)

Build a mental (or physical) map of relations between various results and concepts. For example, let’s say you want to determine whether a series converges or not. A useful thing to realize is that it is easier to determine whether a series with positive terms converges than an arbitrary series because there are more tests available for this case. Another useful thing to know is that if the series converges absolutely, it also converges; so in some cases even if the series doesn’t have positive terms you can reduce it to the easier case. Knowing all those relations and results before you start the problem will help you to decide on a good strategy to attack the problem. Not knowing them in advance will often cause you to go astray.

在脑海中或纸上构建 “概念 - 结论” 关联图。例如,判断级数敛散性时,要知道 “正项级数比任意级数更易判断”(因有更多判别法可用),且 “绝对收敛的级数必收敛”—— 因此即便遇到非正项级数,也可先转化为正项级数判断绝对收敛性。提前掌握这些关联,能帮你制定高效解题策略;反之则易走弯路。

7.不怕写错,但忌 “不懂装懂”(Don’t fear mistakes, but avoid writing what you don’t understand)

Don’t be afraid of writing something wrong. Be hesitant of writing something that you don’t really understand. It’s not that bad if you write something like “All operators are diagonalizable, hence

X

X

X” because once you understand that not all operators are diagonalizable, you’ll immediately see the error. But if you write a convoluted argument two pages long which uses somewhere the fact that your operator is diagonalizable, it will be much more difficult to discover and learn from the error.

别怕写错,但要谨慎写下自己不理解的内容。比如你写 “所有算子均可对角化,故

X

X

X 成立”,即便错了,后续理解 “并非所有算子都可对角化” 时,也能立刻发现问题;但如果写了两页复杂推导,却在某处隐性依赖 “算子可对角化” 的错误前提,就很难发现问题,更谈不上从错误中学习。

8.夯实计算能力(Develop decent computational skills)

Math is hard enough without being bogged down in computation errors and wrong applications of techniques. For example, when learning how to solve a general linear system of equations, sit down and solve 77 different systems. If you got a wrong result in 55 of the 77 cases, something is fishy. Identify clearly the origin of the mistake in each case (is it an arithmetic error? did you apply the algorithm incorrectly?). Then repeat with 77 other systems until you get at least 66 correct.

数学本身已足够复杂,别让计算错误和方法误用拖后腿。例如,学习解线性方程组时,可集中练习 77 个不同方程组:若 77 题中有 55 题出错,需明确错误根源(是算术错误?还是算法应用错误?);再用另外 77 题重复练习,直到正确率至少达到 66 题。

9.与他人协作解题(Work on math with others)

Try to work on math problems with other people. By that I don’t mean asking other people for solutions to exercises you couldn’t solve. Try to find someone which is more or less your level and has good communication and interpersonal skills and work together with them all the way through a few problems. Be active, propose some ideas, listen to the other person’s ideas and work together. This way, you’ll get exposed to techniques that work for other people, their mental maps and ideas about the concepts involved and you’ll be able to adapt and implement what you learn as part of your own skill set if you find it helpful.

尝试与他人一起解题,但并非直接索要不会做的题的答案。找一位水平相近、善于沟通的伙伴,共同完整解决几道题:主动提出思路、倾听对方想法、协作推进。这样你能接触到他人的解题技巧、概念关联逻辑,若觉得有用,可将其融入自己的方法体系。

回答 2:Stella Biderman(Apr 16, 2017 at 22:54,38)

EDIT: I misunderstood the OP at first, and the first half of my answer gives advice on how to approach proving an unknown problem. I then tie this into the organizational question the OP is really asking below the line.

编辑:起初我误解了提问者的需求,回答前半部分聚焦 “如何证明未知问题”,后半部分会结合提问者真正关心的 “推导过程组织方式” 展开。

核心方法:以 “例子” 驱动数学学习(Examples, examples, examples!)

For me, pretty much all of mathematics is driven visually and by example.

对我而言,几乎所有数学学习都靠 “视觉化” 和 “例子” 推动。

Every time you see a theorem, first seriously commit yourself to finding a counter example. Find almost-counterexamples that show why every assumption in the problem is necessary. Then for each of those almost-counterexamples find an example that is extremely similar, except satisfies the assumption the counterexample was missing. Now you’re ready to prove the theorem or read its proof, and in all likelihood you’re already close to the proof.

每次遇到定理,先认真尝试找 “反例”:通过 “近似反例”(即不满足某一前提假设、导致定理不成立的例子),理解定理中每个前提的必要性;再针对每个 “近似反例”,构造一个仅补充缺失前提、其余条件完全相同的 “正例”。完成这一步后,你不仅能更轻松地证明或理解定理,甚至可能已接近定理的证明思路。

案例:惠特尼(Hassler Whitney)验证贝祖定理(Bezout’s Theorem)

There’s a great anecdote about this by Keith Kendig about Hassler Whitney:

基思・肯迪格(Keith Kendig)曾讲述过哈斯勒・惠特尼的一则轶事,恰好能说明这一方法:

One day in his office, I happened to mention Bezout’s theorem which basically says that two curves of degree m m m and n n n respectively intersect in m n mn mn points. He says he never heard of it and seems galvanized by it. He jumps up and heads to the blackboard, saying “Let’s see if I can disprove that” Disprove it?! “Wait a minute!” I say, “that theorem is nearly two centuries old! You can’t disprove anything… really…” As he begins to working on some counterexamples at the blackboard I see my well-meant words are simply static.

有天在他办公室,我偶然提到贝祖定理 —— 大致是说 “ m m m 次曲线与 n n n 次曲线交于 m n mn mn 个点”。他说从未听过这个定理,却立刻来了兴致,跳起来走向黑板:“我来试试能不能推翻它。” 我连忙阻拦:“这定理都快两百年了!不可能推翻的…… 真的。” 但他已经开始在黑板上构造反例,我的话完全没起作用。

His first tries were easy to demolish, but he was a fast learner, and ideas soon surfaced about the complex line at infinity and how to count multiple points of intersection. After a while it got harder for me to justify the theorem, and when he asked “What about two concentric circles?” I had no answer. He argued his way through and eventually found all four points. Finally he was satisfied, and the piece of chalk was given a rest. He backed away from the blackboard and said “Well, well - that is quite a theorem, isn’t it?”

他最初的反例很容易被反驳,但他学东西很快,没多久就想到了 “无穷远复直线” 和 “交点重数计算” 的思路。后来我越来越难辩解,当他问 “那两个同心圆呢?” 时,我彻底答不上来。他却一步步推导,最终找到了全部 4 个交点。最后他终于满意地放下粉笔,退到一边说:“嗯,这定理确实不简单,是吧?”

I think I mostly kept my cool during all of this, but after I left his office I realized I was pretty shaken. I remember thinking to myself. “Golly, Kendig, you just saw how one of the giants does it!” He’d taken the theorem to the mat, wrestled with it, and the theorem won. I’d known about that result for at least two years, but in 15 or 20 minutes he’d gained a deeper appreciation of it than I’d ever had. In retrospect, it represented a turning point for me: I began to think examples, examples, examples. Whitney worked by finding an example that contained the essential crux of a problem, and then worked relentlessly on it until he crack it.

当时我表面还算镇定,但离开办公室后却深受震撼。我心想:“肯迪格,你刚刚见证了大师的思考方式!” 他带着质疑与定理 “搏斗”,最终理解了定理的精髓。我虽然知道这个定理两年多,但他只用 15 到 20 分钟,就比我理解得更深刻。这件事成了我的转折点:我开始意识到 “例子” 的重要性 —— 惠特尼的方法,就是找到包含问题核心的例子,然后死磕到底,直到破解关键。

Doing mathematics by example has taught me how to feel the shape of a theorem, to naturally divide mathematical objects into collections based on how the theorem divides them into “examples” and “non-examples” and those lines that the theorem draw shows you how to prove the theorem. This will also massively help you recreate the proof in the future.

通过 “例子” 学数学,能让你 “感知定理的结构”:根据定理对 “正例” 和 “反例” 的划分,自然梳理数学对象的分类;而定理划分 “正 / 反例” 的边界,其实就是证明定理的关键思路。这种方法还能帮你在日后更轻松地回忆起定理的证明过程。

延伸:从 “反向” 思考定理(Think in the “wrong direction”)

Thinking about the theorem from the “wrong direction” will teach you to think in unusual ways help you falsify conjectures and assumptions easier. People have a strong bias towards looking for confirmation of facts, but struggle to remember to look for disconfirmation. This can make it hard to understand theorems, because

Z

[

−

5

]

\mathbb {Z}[\sqrt {-5}]

Z[−5] tells you a hell of a lot more about the nature of prime factorization than

Z

\mathbb {Z}

Z does. There’s a famous quote about the importance of this kind of thinking about the philosopher and logician Wittgenstein (source):

从 “反向”(即尝试推翻、质疑)思考定理,能帮你突破常规思维,更易发现猜想或假设中的漏洞。人们往往习惯 “验证事实”,却忽略 “寻找反证”—— 但这恰恰是理解定理的关键:比如,从

Z

[

−

5

]

\mathbb {Z}[\sqrt {-5}]

Z[−5](其中质因数分解不唯一)中,能比从

Z

\mathbb {Z}

Z(质因数分解唯一)中更深刻地理解 “质因数分解” 的本质。哲学家、逻辑学家维特根斯坦的名言,恰好说明了这种思维的重要性:

Tell me,"Wittgenstein asked a friend,“why do people always say, it was natural for man to assume that the sun went round the earth rather than that the earth was rotating?”

“告诉我,” 维特根斯坦问朋友,“为什么人们总说‘人类自然会认为太阳绕地球转,而非地球自转’?”

His friend replied, “Well, obviously because it just looks as though the Sun is going round the Earth.”

朋友答:“很明显啊,因为看起来太阳就是在绕地球转。”

Wittgenstein replied, “Well, what would it have looked like if it had looked as though the Earth was rotating?”

维特根斯坦反问:“那如果‘地球自转’的现象真的存在,它看起来会是怎样的?”

Here’s a MathOverflow link about counterexamples to get to know and love: [链接内容略,原回答含具体链接]

这里有一个 MathOverflow 上关于 “反例” 的链接,推荐你去了解和学习(原回答含具体链接)。

结合提问者需求:推导过程的组织方式

Now, to tie this into the actual questions in the OP:

接下来,针对提问者真正关心的 “推导过程组织方式”,我的建议如下:

For example, do you have two separate pieces of paper for intermediate results and for details?

例如,你是否用两张分开的纸分别记录中间结果和细节步骤?

That depends on the flow of the proof. I’m a big chalk-boarder, and often sketch out my proofs and my examples on chalkboards before committing them to paper (or TeX, more commonly). If proving an intermediate result seriously disrupts the flow of the proof (which tends to mean “requires more than a paragraph”), then in my proof sketch I’ll just write “by Padding Lemma” or whatever and then prove the “Padding Lemma” on a different pane of the chalkboard. This is largely because I want to be able to look at my examples and proof sketch without getting bogged down in the combinatorics of this lemma I happen to be using. In the actual write up of the proof, learning how to properly organize your “digressions” is a very important part of learning to do academic writing, but is heavily contextual. Like organizing stories or essays, it’s more of an art than a skill.

取决于证明的 “流程连贯性”。我习惯用黑板:在写进纸稿(或更常用的 TeX 文档)前,会先在黑板上勾勒证明框架和例子。若某个中间结果的证明会严重打断主线(通常指需要超过一段的篇幅),我会在框架中简记 “由填充引理(Padding Lemma)得”,再在黑板的另一区域单独证明 “填充引理”。这样做是为了避免被引理的细节(比如组合逻辑)干扰,能清晰看到整体框架和例子。实际撰写证明时,学会合理安排 “支线内容”(如引理证明)是学术写作的重要部分,但它高度依赖上下文 —— 就像组织故事或散文,更偏向 “艺术” 而非固定 “技巧”。

Are there any specific ways of organizing your derivations on paper, or in notebooks, that help clear your mind?

是否有特定的方式,能在纸上或笔记本中组织推导过程,从而帮助理清思路?

For me, the process of designing a proof (and in fact, thinking in general) is like a conversation. I create an interlocutor in my mind and argue with them. I walk them through example and non-example, explaining why in each case the theorem holds or fails. I find that doing so helps me focus on the similarity between the examples and find the underlying logical thread that contains the “real reason” that the theorem is true. I might draw diagrams or do a few calculations on paper if I can fit them in my head, but I generally don’t start really writing the proof until I know what’s going to happen. At that point, I chart out a few examples that have been particularly enlightening and that can guide my thinking on a chalkboard. This is usually a few pictures and equations, the equations written with the pictures, and each example separated in space. Then I’ll sit down somewhere that I can see the whole chalkboard and begin to write.

对我而言,设计证明(甚至一般思考)的过程就像 “对话”:在脑海中设定一个 “对手”,和 TA 争论 —— 通过正例、反例一步步引导 TA,解释定理在不同情况下成立或不成立的原因。这个过程能帮我聚焦例子间的共性,找到定理成立的 “核心逻辑线”。若脑海中装不下细节,我会在纸上画图表或做简单计算,但在明确整体思路前,绝不会贸然开始写完整证明。当思路清晰后,我会在黑板上列出几个最有启发的例子(通常是图表配公式,每个例子分开排列),再找个能看到整个黑板的位置坐下,开始整理成文字。

Do you write everything linearly, from top to bottom of your notebook, or do you go back and forth on your scrap paper, only writing it linearly when you’ve found the result?

你是从笔记本顶部到底部线性地记录所有内容,还是在草稿纸上反复修改,直到得出结果后才线性整理?

As I mentioned, I sort my thoughts by example, with each example being an explication of why the theorem is true for that example. I tend to separate examples horizontally, and organize their explication either vertically (especially for formula-heavy problems) or circularly (especially for graphic-heavy problems). I don’t worry too much about the arrangement of my chalkboard though, and just place things “where they obviously fit.”

如前所述,我按 “例子” 整理思路 —— 每个例子都用来解释 “定理为何对它成立”。我会把例子横向分开排列,解释部分则根据内容选择:公式多的问题用 “纵向排版”,图表多的问题用 “环形排版”(围绕图表展开)。不过我不太纠结黑板的布局,只把内容放在 “看起来自然的位置”。

Do you scratch formulae completely if you’ve made a mistake, and start over, or do you just correct the formulae?

若出现错误,你会将公式完全划掉重新开始,还是仅修正错误部分?

I prefer working on a chalkboard and erasing mistakes and fixing them. In particular, I avoid slashing through or using other markings to indicate that a term is incorrect, because my equations are often adjacent to arrows and other markings that indicate how they fit together, and I use crossing out to indicate cancellation.

我更喜欢用黑板:直接擦掉错误部分并修正。尤其避免用斜线划掉错误项 —— 因为我的公式旁常标注箭头等 “关联符号”,用来表示推导逻辑,而斜线会被我专门用来表示 “抵消”(如代数中的项抵消),避免混淆。

Do you write derivations quickly on a scratchbook, until you’ve found the final answer, or do you write them neatly from start to finish?

你是在草稿本上快速记录推导过程,直到得出最终答案,还是从头到尾都工整书写?

My handwriting is not that neat, and I usually TeX the final. If it’s legible to me (and any collaborators), that’s all that’s necessary for scratch work.

我的字迹本就不工整,最终稿通常用 TeX 排版。草稿只要我自己(和合作者,若有)能看懂就行,不必追求工整。

对该回答的评论

1.Readin(Apr 17, 2017 at 0:43):I think the questioner wants to know how to keep his thoughts organized. There is a goal to the problem. There are intermediate results. There are intermediate results that need to be pulled together to form other intermediate results. The page presenting the proof has to stay organized, but so does one’s mind. Context switches as one goes from one part of the proof to another can be disrupting. You may go down a path that fails and the results need to be discarded and forgotten. How do you avoid cluttering the page and your mind? At least that is how I interpret the question.

我认为提问者想知道的是如何保持思路有条理。解题有明确目标,过程中会产生中间结果,有些中间结果还需要整合起来形成新的中间结果。不仅呈现证明的页面要保持整洁,思路也得清晰。从证明的一个部分切换到另一部分时,上下文转换可能会造成干扰;你可能会尝试一条走不通的思路,其结果需要被舍弃和遗忘。该如何避免页面和大脑陷入混乱呢?至少我是这样理解这个问题的。

2.Stella Biderman(Apr 20, 2017 at 15:17,回复 Readin):@Programmer2134 I hope you found my edited answer helpful.

@Programmer2134(推测为提问者相关账号),希望你觉得我修改后的回答有帮助。

3.user56834(Apr 20, 2017 at 15:36,回复 Stella Biderman):I definitely did, and upvoted it.

我确实觉得有帮助,并且给你点了赞。

4.Stella Biderman(Sep 23, 2020 at 18:32,回复 Readin):@Readin It’s several years late, but I finally found the story I mentioned in my original answer. It’s about Hassler Whitney, and I’ve edited it into the answer.

@Readin,虽然已经过去好几年了,但我终于找到了最初回答中提到的那个故事。它是关于哈斯勒・惠特尼的,我已经把它补充到回答里了。

5.Stella Biderman(Nov 28, 2020 at 0:56,回复 Readin):@Readin Indeed. I’ve wanting to bring up that anecdote from time to time and was never able to figure it out until just two months ago. Now I have it, and will always be able to find it in this comment.

@Readin,确实如此。我一直时不时想提起那个轶事,但直到两个月前才找到相关细节。现在我把它记下来了,以后在这条评论里就能随时找到。

回答 3:Jair Taylor(Apr 17, 2017 at 0:02,20)

Everyone is confused when learning a new subject, so don’t get discouraged if you don’t pick things up immediately. My advice would be: instead of letting the confusion scare you away,harness your confusion for all it is worth.

学习新学科时,每个人都会感到困惑。如果不能马上掌握知识,不要气馁。我的建议是:不要让困惑把你吓退,而是要充分利用困惑的价值。

困惑的两种类型及应对

There are many different kinds of confusion. Sometimes it may be just a sort of general haziness around a subject - this might just indicate you need to re-read the textbook because you don’t remember the details.

困惑有很多种类型。有时可能只是对某个主题整体感到模糊 —— 这通常意味着你需要重新阅读课本,因为你忘记了细节。

But there is another kind of confusion, one that is potentially useful. Often you will have some sort of cognitive dissonance. That is, you’re learning something new - but it does not jive with your current understanding. Something does not feel right. One difference between an excellent student and a mediocre one is that the excellent student will simply refuse to let this feeling go until it is resolved. It’s very easy to accept what you’ve just learned, even if it doesn’t make sense to you. But if you’re feeling this kind of cognitive dissonance, it means something is wrong in your understanding, either of the previous material or of what you’re currently learning.

但还有一种困惑具有潜在价值,那就是常出现的认知失调:你在学习新内容时,发现它与现有认知不相符,总觉得 “不对劲”。优秀学生和普通学生的区别之一,就在于优秀学生会坚持解决这种不适感,直到困惑消除。人们很容易接受刚学到的知识,即便它对自己而言毫无逻辑,但如果出现认知失调,就说明你的理解存在问题 —— 要么是对之前知识的理解有误,要么是对当前内容的认知不到位。

利用困惑的关键:将其转化为精准问题

The trick is to be able to precisely pinpoint what the issue is. At first what you might feel is only an emotion, a vague uncertainty. But this uncertainty may be meaningful. If you double down on this, and keep thinking about it, eventually some more concrete questions will bubble to the surface. It’s okay to not have the answer immediately - the important thing is to sharpen the confusion into a very precise question. This will often involve taking away all of the extraneous details surrounding your question and focusing only on precisely where the issue is. If you’re having an issue with a very general theorem or idea, try coming up with a specific, concrete example that demonstrates the problem.

关键在于精准定位问题核心。起初,你可能只感受到一种模糊的不确定情绪,但这种情绪可能暗藏关键信息。如果你聚焦这种感受、持续思考,最终会浮现出更具体的疑问。暂时没有答案没关系,重要的是把模糊的困惑转化为精准的问题 —— 这通常需要剔除问题周边的无关细节,只聚焦于矛盾的核心。如果对某个通用定理或概念感到困惑,不妨构造一个能体现该问题的具体例子。

Once you’ve funneled the haziness into a very specific question, you’ll often find that the answer is not as difficult as you thought. If you can’t come up with it after some thought, you should ask your a classmate, instructor or a TA - or ask here on Stack Exchange. Generally speaking, I think teachers appreciate getting very well-formed questions that show the student has put a lot of thought into it.

一旦将模糊困惑转化为具体问题,你常会发现答案并没有想象中那么难。若思考后仍无头绪,可向同学、老师或助教请教,也可以在 Stack Exchange 上提问。通常来说,老师会更欣赏那些逻辑清晰、能体现学生深度思考的问题。

注意事项:避免过度纠结次要问题

It is possible to take this too far, getting bogged down in minor issues instead of moving on with the material. Sometimes it’s necessary to table a question so you can get on with your studying. In that case, my advice would be to write down your confusion and remember to come back to it later. Sometimes you just need to take a walk, or sleep on it. Channeling confusion into a meaningful question is a difficult skill that takes time and practice.

但也要避免过度纠结:若在次要问题上停滞不前,会影响整体学习进度。有时需要先把问题搁置,继续推进学习。这种情况下,建议你写下困惑,提醒自己之后再回头解决。有时,散步或睡一觉后再思考,思路会更清晰。将困惑转化为有意义的问题是一项困难的技能,需要时间和练习才能掌握。

补充:认知失调解决过程示意图

Edit:

编辑:

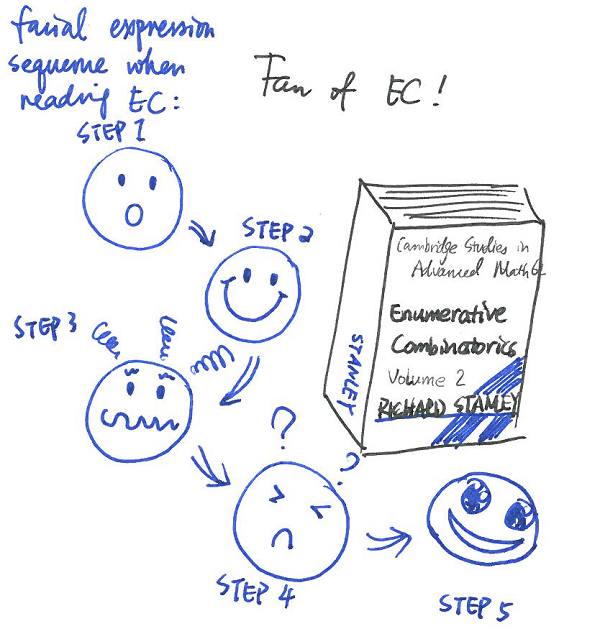

Here’s an illustration of the process. Many students don’t actually get from Step 3 to Step 4. (Cartoon due to Fan Wei, found on the page for Richard Stanley’s Enumerative Combinatorics.)

这里有一张图展示这个过程(许多学生其实无法从步骤 3 推进到步骤 4)。(漫画作者为范薇,来源于理查德・斯坦利《计数组合学》的相关页面)

回答 4:A. Thomas Yerger(Apr 16, 2017 at 22:41,11)

I had a conversation with a friend of mine who at one point felt similarly about writing. While I could never hope to do his view 100% justice, I can attempt to explain how he conquered his situation with writing, and how it helped him to grow mathematically. There are a few caveats. For example, without knowing how you and he compare in mathematical ability (you now compared to him then), I can’t say for sure if this advice will be useful to you. You may also just find that what worked for him does not work for you. I regard my friend as one of the most disciplined people I know, and so he has quite a bit of time in his day to spend on mathematics, and in thought, where I personally would feel tired for the day.

我曾和一位朋友聊过,他以前在写作上也有类似的困惑。虽然我无法完全准确地传达他的观点,但可以试着解释他是如何克服写作困境的,以及这种方法如何帮助他在数学上取得进步。不过有几点需要说明:比如,由于不清楚你和他(当时的他)在数学能力上的差异,我无法确定这些建议对你是否完全适用;你也可能会发现,对他有效的方法并不适合你。我认为他是我认识的最自律的人之一,所以他每天能有大量时间投入数学学习和思考,而换作我,可能早就觉得疲惫了。

核心方法:“记忆→阐释” 的学习循环(Memorize → Explicate)

With that said, my friend’s position was more or less the following: the art of learning is a lost art. At one point in our history, we learned first by memorizing. Now memorizing has quite a bit of stigma associated with it, as if it’s not real learning. This is kind of true, if the only thing you do is memorize. There are many students in schools these days who have memorized a great many theorems who understand virtually nothing, let me say that this is not what I advocate. What is true though, is that having a large class of theorems and proofs that you have memorized will be the foundation of your mathematical ability.

尽管如此,我朋友的核心观点大致如下:学习的艺术是一门 “失传的艺术”。在历史上的某个时期,人们学习的第一步是记忆。如今,“记忆” 却带有不少负面标签,仿佛它不是真正的学习。如果只靠记忆,这种质疑确实有道理 —— 现在很多学生记住了大量定理,却几乎不理解其内涵,我要强调,这并非我所提倡的。但不可否认的是,记住大量定理和证明,是构建数学能力的基础。

类比写作:从模仿到形成个人风格

When my buddy wanted to learn how to write, he had a similar problem. His writing was disorganized, and reflected a certain amount of aimlessness. He found that without a clear purpose or a target audience for who to write to, his writing would suffer greatly. It was also his experience that although he knew how to compose sentences, he did not know how to be a good writer, or even how to really improve.

我朋友当初想学习写作时,也面临类似问题:写作缺乏条理,目标模糊。他发现,若没有明确的写作目的或目标读者,写出的内容会非常糟糕。他还意识到,虽然自己知道如何造句,但不知道如何成为一名好作家,甚至不知道该如何真正提升写作水平。

The solution he came up with was to begin by copying. He would learn to write first by imitation, the way one learns an instrument. Before one composes a masterpiece, they learn other masters’ works inside and out, and learn from their styles. Find a passage of a text that spoke to him, and just copy it word for word. Read it out loud several different ways, find the voice with which the passage was written. Then, when the sentences start to stick to your brain, try to summarize the piece. Try to re-express the same thoughts in your own words.

他想出的解决办法是从 “模仿” 开始。他先通过模仿学习写作,就像人们学习乐器一样 —— 在创作杰作之前,会彻底钻研其他大师的作品,学习他们的风格。他会找一段能引起共鸣的文字,逐字逐句抄写;用不同方式大声朗读,感受文字的 “语调” 和风格;当这些句子在脑海中留下印象后,尝试总结这段文字,并用自己的话重新表达相同的观点。

At first, when you do this, the things you copy and your summaries will be pretty shoddy. They will have little additional insight (although you might find in your summaries things you don’t actually understand about the passage, and this is very important both in writing and in math), and they will sound rather dry. But if you do this with many authors and many passages, you will develop what I can best describe as taste in writing. You’ll learn certain kinds of things that just sound right to your ear, and this will be your writing voice.

起初,抄写的内容和总结可能很粗糙:几乎没有额外的见解(不过,你可能会在总结中发现自己其实没理解的内容 —— 这一点在写作和数学中都非常重要),而且表达会很枯燥。但如果针对多位作者的多篇文字反复练习,你会逐渐培养出一种 “写作品味”—— 能感知到哪些表达 “听起来更恰当”,进而形成自己的写作风格。

迁移到数学:从模仿证明到形成个人思路

This is also what it is like to learn math. You start by copying and reproducing proofs over and over until you have them memorized. Many people like to do some of the things outlined in levap’s answer, like dropping hypotheses. When you reproduce the proofs, try to fill in the proof with some prose about what you are doing and why, like you are lecturing. This is similarly your mathematical voice, and learning to write mathematically is not all that different than writing prose, even if the styles may be different.

学习数学也是如此。首先,反复抄写和重现证明,直到记住它们。你还可以结合 levap 回答中提到的方法(如 “去掉前提假设”)进行练习。在重现证明时,试着像讲课一样,用文字补充说明 “你在做什么” 以及 “为什么这么做”。这就是你的 “数学表达风格”—— 尽管数学写作和散文写作的风格不同,但本质上并无太大差异。

Personally, I find it incredibly helpful to write about mathematics to help me process the ideas. I find that graduate school does not afford me the time I would like to do all the writing I would do otherwise. Of course, one cannot write a book about every subject one takes a class in, but when I venture off in my own direction, I find it helpful to write notes in my mathematical voice, filling things in as best I can.

就我个人而言,通过 “写数学” 来梳理思路非常有帮助。不过我发现,研究生院的学习节奏让我难以有足够时间进行大量写作。当然,没人能为每门课都写一本笔记,但当我自主探索某个数学方向时,会用自己的 “数学风格” 写笔记,尽可能补充细节,这对我的理解很有帮助。

Anyway, I feel in some sense that I have not 100% addressed your question. I guess what I’m really shooting for here is that the process of memorize -> explicate is a fundamental process for learning math. It will equip you with tools to say what’s on your mind, which seems to be something you are struggling with, and it will also help you improve your mathematical writing too. So I will say that as much as time permits, you should try to reproduce proofs, at first word for word, but eventually in your own voice, and maybe even you will be able to give alternative proofs using your newly refined intuition.

总之,我觉得在某种程度上,我并没有完全解答你的问题。但我真正想强调的是:“记忆→阐释” 是学习数学的基础流程。这个流程能帮你掌握 “表达思路” 的方法(这似乎正是你目前面临的困难),还能提升你的数学写作能力。因此,在时间允许的情况下,你应该尝试重现证明 —— 起初可以逐字逐句,最终用自己的风格表达;甚至,你可能会凭借新提炼的直觉,给出不同的证明方法。

对该回答的评论

1.Readin(Apr 16, 2017 at 23:32):Where would one go to find good examples of proofs to copy and memorize? We all know Shakespeare and it is easy enough to learn of other writers with good prose. But mathematicians are generally well-known for their results, not for how well their results are explained. Can you recommend some good proof-writers?

人们应该去哪里寻找适合抄写和记忆的优质证明案例呢?我们都知道莎士比亚,也很容易找到其他散文写得好的作家。但数学家通常因他们的研究成果而闻名,而非对成果的阐释能力。你能推荐一些擅长写证明的数学家(或相关书籍)吗?

2.A. Thomas Yerger(Apr 17, 2017 at 1:15,回复 Readin):A good part of it depends on what you want to learn. Some personal favorite textbooks I’ve worked through in some serious detail are Axler’s Linear Algebra Done Right, Spivak’s A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry I, and Strichartz The Way of Analysis. Each of these is good for one of the main branches of math, and all three are written by excellent writers. Although I have never read Simmons’ book in topology, I have read other texts by Simmons, and have found his writing style to be influential for me, so you might try that for a good book in topology.

这很大程度上取决于你想学习的数学领域。我个人深入研读并非常推荐的教材有:阿克塞尔(Axler)的《线性代数应该这样学》(Linear Algebra Done Right)、斯皮瓦克(Spivak)的《微分几何初步》第一卷(A Comprehensive Introduction to Differential Geometry I),以及斯特里查茨(Strichartz)的《分析学之道》(The Way of Analysis)。这三本书分别覆盖数学的一个主要分支,且作者的阐释能力都非常出色。虽然我没读过西蒙斯(Simmons)的拓扑学著作,但读过他的其他作品,发现他的写作风格对我影响很大,所以如果你想找拓扑学的优质教材,可以试试他的书。

3.Readin(Apr 18, 2017 at 3:30):

Thanks. That’s good to know.

谢谢,这很有帮助。

数学习惯实践

针对 “提升数学实践能力” 的核心习惯,涵盖概念理解、解题流程、推导组织、心态调整四大维度,具体如下:

1. 概念理解:以 “例子 + 关联” 夯实基础

- 多举正例与反例:对每个定理 / 概念,不仅要能列举典型例子(如向量空间的 R n \mathbb {R}^n Rn),还要构造 “反例” 或 “近似反例”(如非子空间的集合),理解前提假设的必要性(如惠特尼验证贝祖定理的思路)。

- 建立心理图像与关联图:为抽象概念绑定具象图像(如用 R 3 \mathbb {R}^3 R3 的直和分解理解 “直和”),并梳理概念间的逻辑关系(如 “正项级数敛散性→绝对收敛→任意级数敛散性” 的推导链),避免孤立记忆。

2. 解题流程:从 “简化→突破→验证” 分步推进

- 先简化模型再推广:面对复杂问题,先从极简单场景入手(如将向量空间假设为 1 维 / 0 维),通过解决简化问题积累信心与思路,再逐步推广到一般情况。

- 利用困惑定位关键问题:遇到 “认知失调”(新内容与现有认知冲突)时,不回避而是将其转化为精准问题(如 “为什么两个同心圆仍满足贝祖定理的交点数?”),必要时通过例子拆解矛盾。

- 验证与复盘:解题后通过 “代入结果验证”“去掉前提假设看矛盾” 等方式检查正确性,同时复盘思路:关键步骤是什么?是否有更优方法?

3. 推导组织:灵活适配 “流程与载体”

- 载体选择与分区:草稿阶段可用黑板 / 草稿纸灵活分区(如主线推导与中间引理分开书写),避免细节干扰整体思路;最终整理时用 TeX 或笔记本线性呈现,确保逻辑连贯。

- 标记与修正技巧:对重要中间结果用特殊符号标记(如提问者的 “方框 + 实心圆”);出错时优先局部修正(如黑板擦除),避免因划掉重写导致思路断裂,草稿以 “自己能看懂” 为核心标准。

- 模仿与形成个人风格:初期可模仿优质教材的推导结构(如《线性代数应该这样学》的证明逻辑),用 “讲课式” 语言补充推导理由(如 “此处用拉格朗日中值定理是因为需建立函数增量与导数的关系”),逐步形成清晰的个人表达风格。

4. 心态与协作:拒绝 “完美主义”,善用外部支持

- 不怕错,但忌 “不懂装懂”:允许推导中出现错误(如误判 “所有算子可对角化”),但避免写连自己都不理解的复杂论证,错误是修正认知的重要机会。

- 与他人协作解题:找水平相近的伙伴共同攻克难题,通过 “提出思路→倾听反馈” 接触不同解题视角,补充自身思维盲区(如学习他人用图表整理数据的方法)。

- 合理搁置与回顾:若陷入次要问题的纠结,可先记录困惑(如 “为什么这个积分换元后结果不变?”),继续推进主线学习,后续通过复习或请教解决,避免停滞不前。

用 “简化模型法” 解决数学问题

以 “证明闭区间上连续函数的有界性” 为例

“简化模型法” 的核心逻辑是:先攻克 “极端简单、条件特殊” 的场景,再从简化模型的解法中提炼通用思路,逐步推广到一般问题。下面以数学分析中的经典定理 —— “闭区间 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上的连续函数 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 必在 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上有界” 为例,完整演示该方法的应用过程。

第一步:明确原问题与核心难点

原问题

设函数 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在闭区间 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上连续,证明:存在常数 M > 0 M > 0 M>0,使得对所有 x ∈ [ a , b ] x \in [a,b] x∈[a,b],都有 ∣ f ( x ) ∣ ≤ M |f(x)| \leq M ∣f(x)∣≤M(即 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上有界)。

难点

“闭区间 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b]” 是 “无穷多个点的集合”,无法直接验证每个点的函数值是否都被某个常数控制;且 “连续性” 是局部性质(每个点的邻域内函数值趋近于该点函数值),如何将 “局部有界” 推广到 “全局有界”,是问题的关键。

第二步:构造简化模型,解决特殊场景

我们从 “最简单、条件最特殊” 的闭区间入手,先解决简化模型的有界性,再观察规律。

简化模型 1:闭区间退化为 “单点集” [ c , c ] [c,c] [c,c]( c c c 为常数)

- 简化逻辑:单点集是闭区间的 “极端情况” —— 区间内只有 1 个点,无需考虑 “多个点的函数值控制”,可直接利用连续性的局部性质。

- 证明简化模型的有界性:

函数 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ c , c ] [c,c] [c,c] 上连续,根据 “连续性的局部定义”:对任意 ε = 1 \varepsilon = 1 ε=1(取任意正数均可),存在 δ > 0 \delta > 0 δ>0,当 x ∈ ( c − δ , c + δ ) ∩ [ c , c ] = { c } x \in (c - \delta, c + \delta) \cap [c,c] = \{c\} x∈(c−δ,c+δ)∩[c,c]={c} 时,有 ∣ f ( x ) − f ( c ) ∣ < 1 |f(x) - f(c)| < 1 ∣f(x)−f(c)∣<1。

对 x = c x = c x=c,代入得 ∣ f ( c ) − f ( c ) ∣ = 0 < 1 |f(c) - f(c)| = 0 < 1 ∣f(c)−f(c)∣=0<1,显然成立。此时取 M = ∣ f ( c ) ∣ + 1 M = |f(c)| + 1 M=∣f(c)∣+1,则 ∣ f ( c ) ∣ ≤ M |f(c)| \leq M ∣f(c)∣≤M,即 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在单点集 [ c , c ] [c,c] [c,c] 上有界。

简化模型 2:闭区间为 “长度极小的区间” [ c , c + δ ′ ] [c, c + \delta'] [c,c+δ′]( δ ′ > 0 \delta' > 0 δ′>0,可任意小)

- 简化逻辑:从 “单点” 扩展到 “几乎是单点的小区间”,仍利用连续性的局部性,但开始涉及 “区间内多个点的控制”。

- 证明简化模型的有界性:

因 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 c c c 处连续,对 ε = 1 \varepsilon = 1 ε=1,存在 δ > 0 \delta > 0 δ>0,当 x ∈ ( c − δ , c + δ ) x \in (c - \delta, c + \delta) x∈(c−δ,c+δ) 时, ∣ f ( x ) − f ( c ) ∣ < 1 |f(x) - f(c)| < 1 ∣f(x)−f(c)∣<1。

取简化区间 [ c , c + δ / 2 ] [c, c + \delta/2] [c,c+δ/2](长度 δ / 2 \delta/2 δ/2,完全包含在 ( c − δ , c + δ ) (c - \delta, c + \delta) (c−δ,c+δ) 内),则对所有 x ∈ [ c , c + δ / 2 ] x \in [c, c + \delta/2] x∈[c,c+δ/2],都有:

∣ f ( x ) ∣ = ∣ f ( x ) − f ( c ) + f ( c ) ∣ ≤ ∣ f ( x ) − f ( c ) ∣ + ∣ f ( c ) ∣ < 1 + ∣ f ( c ) ∣ |f(x)| = |f(x) - f(c) + f(c)| \leq |f(x) - f(c)| + |f(c)| < 1 + |f(c)| ∣f(x)∣=∣f(x)−f(c)+f(c)∣≤∣f(x)−f(c)∣+∣f(c)∣<1+∣f(c)∣

取 M = 1 + ∣ f ( c ) ∣ M = 1 + |f(c)| M=1+∣f(c)∣,则 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ c , c + δ / 2 ] [c, c + \delta/2] [c,c+δ/2] 上有界。

简化模型 3:闭区间为 “有限个小区间的并集”(如 [ a , b ] = [ a , c ] ∪ [ c , b ] [a,b] = [a,c] \cup [c,b] [a,b]=[a,c]∪[c,b], c c c 为 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 中点)

- 简化逻辑:从 “1 个小区间” 扩展到 “2 个相邻小区间”,尝试将 “局部有界” 拼接为 “更大范围的有界”。

- 证明简化模型的有界性:

- 对 [ a , c ] [a,c] [a,c]:因 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 c c c 处连续,存在 δ 1 > 0 \delta_1 > 0 δ1>0,使 [ c − δ 1 , c ] ⊂ [ a , c ] [c - \delta_1, c] \subset [a,c] [c−δ1,c]⊂[a,c] 且 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ c − δ 1 , c ] [c - \delta_1, c] [c−δ1,c] 上有界(由模型 2,取 M 1 = 1 + ∣ f ( c ) ∣ M_1 = 1 + |f(c)| M1=1+∣f(c)∣);同理, f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 a a a 处连续,存在 δ 2 > 0 \delta_2 > 0 δ2>0,使 [ a , a + δ 2 ] ⊂ [ a , c ] [a, a + \delta_2] \subset [a,c] [a,a+δ2]⊂[a,c] 且 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ a , a + δ 2 ] [a, a + \delta_2] [a,a+δ2] 上有界(取 M 2 = 1 + ∣ f ( a ) ∣ M_2 = 1 + |f(a)| M2=1+∣f(a)∣)。

- 若 [ a , a + δ 2 ] [a, a + \delta_2] [a,a+δ2] 与 [ c − δ 1 , c ] [c - \delta_1, c] [c−δ1,c] 未覆盖 [ a , c ] [a,c] [a,c],可在剩余区间内重复 “取连续点的局部有界邻域” 操作(因区间长度有限,有限次操作后必能完全覆盖 [ a , c ] [a,c] [a,c]),最终取 M [ a , c ] = max { M 1 , M 2 , … , M k } M_{[a,c]} = \max\{M_1, M_2, \dots, M_k\} M[a,c]=max{M1,M2,…,Mk}( k k k 为覆盖区间个数),则 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ a , c ] [a,c] [a,c] 上有界。

- 同理, f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ c , b ] [c,b] [c,b] 上有界,取 M [ c , b ] = max { M 3 , M 4 , … , M l } M_{[c,b]} = \max\{M_3, M_4, \dots, M_l\} M[c,b]=max{M3,M4,…,Ml}( l l l 为覆盖区间个数)。

- 对 [ a , b ] = [ a , c ] ∪ [ c , b ] [a,b] = [a,c] \cup [c,b] [a,b]=[a,c]∪[c,b],取 M = max { M [ a , c ] , M [ c , b ] } M = \max\{M_{[a,c]}, M_{[c,b]}\} M=max{M[a,c],M[c,b]},则 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上有界。

第三步:从简化模型提炼通用思路,推广到原问题

通过上述 3 个简化模型,我们提炼出 2 个关键规律:

- 局部有界性:连续函数在任意点的 “某个邻域内” 必是有界的(模型 1、2 的核心结论);

- 有限覆盖性:若闭区间能被 “有限个有界邻域” 覆盖,则函数在整个区间上有界(模型 3 的拼接逻辑)。

模型 3 中 “有限个小区间拼接” 的逻辑,已隐含 “用有限覆盖解决无限问题” 的思路,但模型 3 仅针对 “2 个小区间” 的特殊情况;原问题中 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 是任意闭区间,需借助严格的数学定理将 “有限覆盖” 的思路从 “特殊” 推广到 “一般”。基于这两个规律,推广到原问题:

原问题证明(反证法 + 波尔查诺 - 魏尔斯特拉斯定理)

- 假设矛盾:假设 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上无界,则对任意正整数 n n n,存在 x n ∈ [ a , b ] x_n \in [a,b] xn∈[a,b],使得 ∣ f ( x n ) ∣ > n |f(x_n)| > n ∣f(xn)∣>n。

- 提取收敛子列:由 “波尔查诺 - 魏尔斯特拉斯定理”,有界数列 { x n } ⊂ [ a , b ] \{x_n\} \subset [a,b] {xn}⊂[a,b] 必有收敛子列 { x n k } \{x_{n_k}\} {xnk},设 lim k → ∞ x n k = x 0 ∈ [ a , b ] \lim_{k \to \infty} x_{n_k} = x_0 \in [a,b] limk→∞xnk=x0∈[a,b](闭区间内收敛点仍在区间内)。

- 利用局部有界性导出矛盾:因

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) 在

x

0

x_0

x0 处连续,由模型 2 的结论,存在

δ

>

0

\delta > 0

δ>0,使

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) 在

(

x

0

−

δ

,

x

0

+

δ

)

∩

[

a

,

b

]

(x_0 - \delta, x_0 + \delta) \cap [a,b]

(x0−δ,x0+δ)∩[a,b] 上有界,即存在

M

>

0

M > 0

M>0,对所有

x

∈

(

x

0

−

δ

,

x

0

+

δ

)

∩

[

a

,

b

]

x \in (x_0 - \delta, x_0 + \delta) \cap [a,b]

x∈(x0−δ,x0+δ)∩[a,b],有

∣

f

(

x

)

∣

≤

M

|f(x)| \leq M

∣f(x)∣≤M。

但 { x n k } \{x_{n_k}\} {xnk} 收敛于 x 0 x_0 x0,故当 k k k 足够大时, x n k ∈ ( x 0 − δ , x 0 + δ ) ∩ [ a , b ] x_{n_k} \in (x_0 - \delta, x_0 + \delta) \cap [a,b] xnk∈(x0−δ,x0+δ)∩[a,b],此时 ∣ f ( x n k ) ∣ > n k |f(x_{n_k})| > n_k ∣f(xnk)∣>nk。当 n k > M n_k > M nk>M 时, ∣ f ( x n k ) ∣ > M |f(x_{n_k})| > M ∣f(xnk)∣>M,与 “ ∣ f ( x ) ∣ ≤ M |f(x)| \leq M ∣f(x)∣≤M” 矛盾。 - 结论:假设不成立,故 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 在 [ a , b ] [a,b] [a,b] 上有界。

第四步:总结 “简化模型法” 的应用步骤

通过上述案例,可将 “简化模型法” 的核心步骤归纳为 3 步:

- 拆条件:找 “极端特殊” 的简化场景:将原问题的条件弱化到 “最容易验证” 的情况(如闭区间 → 单点集、小区间、有限并集),确保简化模型可直接用已知性质(如连续性的局部定义)解决;

- 找规律:从简化解中提炼通用逻辑:观察简化模型的证明过程,提取可推广的 “核心操作”(如本例中的 “局部有界 → 有限覆盖 → 全局有界”);

- 补工具:用数学定理衔接 “简化” 与 “一般”:当推广到原问题时,若遇到 “无限 → 有限”“局部 → 全局” 的鸿沟,调用相应的数学工具(如本例的波尔查诺 - 魏尔斯特拉斯定理、有限覆盖定理)完成衔接,最终证明原问题。

这种方法的优势在于:先通过简化模型建立 “解题信心”,再逐步拆解难点,避免因问题的 “抽象性” 或 “复杂性” 直接陷入僵局,尤其适用于分析、拓扑等涉及 “无限” 或 “抽象空间” 的数学问题。

将 “简化模型法” 推广到各类数学问题,核心是 抓住问题的 “核心矛盾”,通过剥离次要条件、降低复杂度、转化抽象关系,先解决简化后的基础问题,再反向迁移到原问题。其本质是 “从特殊到一般”“从简单到复杂” 的思维迁移,具体可按 “四步推广框架” 操作,并结合不同类型数学问题的特点调整细节。以下从 “推广逻辑”“分题型应用策略”“典型案例” 三个维度展开,帮助你系统掌握这一方法。

一、简化模型法的通用推广逻辑(四步框架)

无论面对代数、几何、概率还是应用题,推广简化模型法都遵循以下四个核心步骤,关键是每一步都要明确 “简化的依据” 和 “还原的路径”:

| 步骤 | 核心目标 | 操作要点 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. 拆解原问题:定位 “复杂源” | 找到让问题难解决的关键障碍(如多变量、抽象概念、复杂图形、动态变化) | ① 列出所有已知条件和未知量; ② 标记 “非必要条件”(可暂时去掉的细节)和 “核心关系”(如公式、等量关系) |

| 2. 构建简化模型:剥离次要条件 | 基于 “核心关系”,去掉 1 - 2 个 “复杂源”,形成可快速解决的 “基础问题” | ① 优先简化 “动态 / 变化条件” 为 “静态 / 固定条件”; ② 优先简化 “多变量” 为 “单变量”; ③ 确保简化后的问题仍保留原问题的 “核心逻辑”(如行程问题的 “路程 = 速度 × 时间”) |

| 3. 解决简化模型:提炼通用方法 | 用基础数学工具(如方程、几何定理、公式)解决简化问题,总结 “可复用的解题逻辑”(如 “找等量关系列方程”“作辅助线转化图形”) | ① 记录简化问题的解题步骤; ② 标记步骤中 “不依赖于简化条件” 的部分(这是推广到原问题的关键) |

| 4. 还原原问题:逐步叠加复杂条件 | 将之前剥离的 “复杂源” 逐一加回简化模型,用通用方法调整解法,验证每一步的合理性 | ① 每次只叠加一个复杂条件,避免问题再次变复杂; ② 若叠加后解法失效,回溯简化模型的核心逻辑,重新调整 |

二、分题型推广策略(结合典型案例)

不同类型的数学问题,“复杂源” 和 “核心关系” 差异较大,需针对性调整简化方向。以下是四类高频题型的推广思路:

1. 代数问题(如方程、函数、不等式)

核心矛盾:多变量、高次项、参数未知、抽象函数表达式

简化方向:① 用 “具体数值” 代替 “参数”;② 降次(如二次方程 → 一次方程);③ 用 “特殊函数” 代替 “抽象函数”(如一次函数代替未知函数)

案例:求解抽象函数 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 的性质

原问题:已知 f ( x ) f(x) f(x) 是定义在 R \mathbb{R} R 上的奇函数,且对任意 x 1 > x 2 x_1 > x_2 x1>x2,有 f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) > x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) > x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)>x1−x2,求 f ( x ) + x f(x) + x f(x)+x 的单调性。

-

步骤 1:定位复杂源:

抽象函数 f ( x ) f(x) f(x)(无具体表达式)、“ f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) > x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) > x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)>x1−x2” 的抽象关系。

-

步骤 2:构建简化模型:

用 “具体奇函数” 代替抽象 f ( x ) f(x) f(x),选择 f ( x ) = x f(x) = x f(x)=x(满足奇函数,且 f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) = x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) = x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)=x1−x2,与原条件“ f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) > x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) > x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)>x1−x2”仅差不等号方向);将抽象关系简化为 “ f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) = x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) = x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)=x1−x2”。

-

步骤 3:解决简化模型:

求 g ( x ) = f ( x ) + x = x + x = 2 x g(x) = f(x) + x = x + x = 2x g(x)=f(x)+x=x+x=2x 的单调性——显然是 R \mathbb{R} R 上的增函数。

通用方法:“构造新函数 g ( x ) = f ( x ) + x g(x) = f(x) + x g(x)=f(x)+x,通过定义法(比较 g ( x 1 ) g(x_1) g(x1) 与 g ( x 2 ) g(x_2) g(x2) 的大小)判断单调性”。

-

步骤 4:还原原问题:

将 “ f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) > x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) > x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)>x1−x2” 还原,用定义法证明 g ( x ) g(x) g(x) 的单调性:

对任意 x 1 > x 2 x_1 > x_2 x1>x2,$g(x_1) - g(x_2) = [f(x_1) + x_1] - [f(x_2) + x_2] = [f(x_1) - f(x_2)]- ( x 2 − x 1 ) (x_2 - x_1) (x2−x1)。由原条件 f ( x 1 ) − f ( x 2 ) > x 1 − x 2 f(x_1) - f(x_2) > x_1 - x_2 f(x1)−f(x2)>x1−x2,代入得:

g ( x 1 ) − g ( x 2 ) > ( x 1 − x 2 ) − ( x 2 − x 1 ) = 2 ( x 1 − x 2 ) g(x_1) - g(x_2) > (x_1 - x_2) - (x_2 - x_1) = 2(x_1 - x_2) g(x1)−g(x2)>(x1−x2)−(x2−x1)=2(x1−x2)。

因 x 1 > x 2 x_1 > x_2 x1>x2,故 2 ( x 1 − x 2 ) > 0 2(x_1 - x_2) > 0 2(x1−x2)>0,即 g ( x 1 ) > g ( x 2 ) g(x_1) > g(x_2) g(x1)>g(x2),因此 g ( x ) = f ( x ) + x g(x) = f(x) + x g(x)=f(x)+x 是 R \mathbb{R} R 上的增函数。

2. 几何问题(如平面几何、立体几何)

核心矛盾:图形复杂(多线段/多面)、动态变化(动点/旋转)、空间想象难(立体几何)

简化方向:① 拆 “复杂图形” 为 “基础图形”(如三角形、矩形);② 变 “动态” 为 “静态”(取动点的特殊位置,如端点、中点);③ 降维(立体几何 → 平面几何,如作截面)

案例:立体几何中动点距离最值

原问题:在棱长为 2 的正方体 A B C D − A 1 B 1 C 1 D 1 ABCD - A_1B_1C_1D_1 ABCD−A1B1C1D1 中,点 P P P 在棱 A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1 上运动,点 Q Q Q 在棱 B C BC BC 上运动,求 P Q PQ PQ 的最小值。

- 步骤 1:定位复杂源: P P P、 Q Q Q 为动点(动态变化)、空间图形(需空间想象)。

- 步骤 2:构建简化模型:① 降维:将正方体的面 A 1 B 1 B A A_1B_1BA A1B1BA(含棱 A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1)与面 A B C D ABCD ABCD(含棱 B C BC BC)沿公共棱 A B AB AB 展开为平面,此时 A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1 与 B C BC BC 在同一平面内且相互平行;② 静态化:取 P P P 为 A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1 中点, Q Q Q 为 B C BC BC 中点,计算两点距离(初步感知规律)。

- 步骤 3:解决简化模型:展开后, A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1 与 B C BC BC 为平行线段,间距等于正方体的棱长(2)。根据 “平面内两平行线间垂线段最短”,此时 P Q PQ PQ 的最短距离为 2。通用方法:“将空间中动点的距离问题,通过 ‘展开相邻面为平面’,转化为平面内 ‘两平行线间垂线段最短’ 的问题”。

- 步骤 4:还原原问题:验证动态情况——无论 P P P 在 A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1、 Q Q Q 在 B C BC BC 上如何运动,展开面后 A 1 B 1 A_1B_1 A1B1 与 B C BC BC 的平行关系不变,两平行线间的垂线段长度恒等于正方体棱长(2)。因此, P Q PQ PQ 的最小值为 2。

3. 概率统计问题(如复杂事件概率、分布列)

核心矛盾:事件包含多个子事件、样本空间大、变量取值多

简化方向:① 减少 “事件维度”(如从 “3 个球” 到 “2 个球”);② 缩小 “样本空间”(如从 “无限次试验” 到 “有限次试验”);③ 用 “等可能事件” 代替 “非等可能事件”

案例:计算多次独立重复试验的概率

原问题:某射手射击命中率为 0.8,连续射击 5 次,求 “至少命中 3 次” 的概率。

- 步骤 1:定位复杂源:“至少 3 次” 包含 “命中 3 次、4 次、5 次” 三个子事件(计算量大);射击次数为 5 次(多轮试验)。

- 步骤 2:构建简化模型:① 减少射击次数:改为 “连续射击 2 次,求至少命中 1 次的概率”;② 减少子事件:“至少 1 次” 仅包含 “命中 1 次、2 次”(2 个子事件,更易计算)。

- 步骤 3:解决简化模型:用 “对立事件” 简化计算——“至少命中 1 次” 的对立事件是 “全未命中”。根据独立事件概率公式:

P ( 全未命中 ) = ( 1 − 0.8 ) 2 = 0.04 P(\text{全未命中}) = (1 - 0.8)^2 = 0.04 P(全未命中)=(1−0.8)2=0.04,

因此 P ( 至少命中 1 次 ) = 1 − 0.04 = 0.96 P(\text{至少命中 1 次}) = 1 - 0.04 = 0.96 P(至少命中 1 次)=1−0.04=0.96。

通用方法:“当 ‘至少 n n n 次’ 的子事件较多时,用 ‘ 1 − 对立事件概率 1 - 对立事件概率 1−对立事件概率’ 计算,避免重复求和”。 - 步骤 4:还原原问题:将射击次数还原为 5 次,“至少命中 3 次” 的对立事件是 “命中 0 次、1 次、2 次”。根据二项分布概率公式

P

(

X

=

k

)

=

C

(

n

,

k

)

p

k

(

1

−

p

)

n

−

k

P(X = k) = C(n,k)p^k(1-p)^{n-k}

P(X=k)=C(n,k)pk(1−p)n−k(其中

n

=

5

n=5

n=5,

p

=

0.8

p=0.8

p=0.8):

P ( 至少命中 3 次 ) = 1 − [ P ( X = 0 ) + P ( X = 1 ) + P ( X = 2 ) ] = 1 − [ C ( 5 , 0 ) 0. 8 0 0. 2 5 + C ( 5 , 1 ) 0. 8 1 0. 2 4 + C ( 5 , 2 ) 0. 8 2 0. 2 3 ] = 1 − [ 0.00032 + 0.0064 + 0.0512 ] = 0.94208 \begin{align*} P(\text{至少命中 3 次}) &= 1 - [P(X=0) + P(X=1) + P(X=2)] \\ &= 1 - [C(5,0)0.8^00.2^5 + C(5,1)0.8^10.2^4 + C(5,2)0.8^20.2^3] \\ &= 1 - [0.00032 + 0.0064 + 0.0512] \\ &= 0.94208 \end{align*} P(至少命中 3 次)=1−[P(X=0)+P(X=1)+P(X=2)]=1−[C(5,0)0.800.25+C(5,1)0.810.24+C(5,2)0.820.23]=1−[0.00032+0.0064+0.0512]=0.94208

4. 实际应用题(如经济利润、工程问题)

核心矛盾:文字信息多、条件交叉(如成本/售价/销量关联)、单位复杂

简化方向:① 用 “表格/图形” 梳理条件(减少文字干扰);② 固定 “多个变量中的一个”(如假设销量为 100 件,简化计算);③ 忽略 “次要成本”(如固定成本暂不计)

案例:经济利润问题(求最大利润)

原问题:某商品进价为 20 元/件,售价 x x x 元/件( x ≥ 20 x \geq 20 x≥20),销量 y y y 件与售价的关系为 y = − 10 x + 500 y = -10x + 500 y=−10x+500,每件还需缴纳管理费 1 元,求最大利润。

- 步骤 1:定位复杂源:销量与售价的函数关系( y = − 10 x + 500 y = -10x + 500 y=−10x+500)、管理费(额外成本)、利润公式涉及 “售价、销量、成本” 三个变量。

- 步骤 2:构建简化模型:① 固定销量:假设销量 y = 100 y = 100 y=100 件(简化变量);② 忽略管理费:单位成本仅为进价 20 元/件。此时利润 L = ( x − 20 ) × 100 L = (x - 20) \times 100 L=(x−20)×100,显然 x x x 越大, L L L 越大(初步明确 “利润 =(单价 - 单位成本)× 销量” 的核心公式)。通用方法:“通过建立利润函数,结合函数性质(如二次函数顶点)求最值”。

- 步骤 3:解决简化模型:若 y = 100 y = 100 y=100,则 L = 100 x − 2000 L = 100x - 2000 L=100x−2000( x ≥ 20 x \geq 20 x≥20), L L L 随 x x x 增大而增大(但需结合原问题中 “销量随售价增大而减小” 的关系修正)。

- 步骤 4:还原原问题:① 加入管理费:单位成本 = 20 + 1 = 21 元;② 还原销量函数

y

=

−

10

x

+

500

y = -10x + 500

y=−10x+500(由销量非负,得

x

≤

50

x \leq 50

x≤50,故定义域为

x

∈

[

21

,

50

]

x \in [21, 50]

x∈[21,50])。

利润函数为:

L = ( x − 21 ) ( − 10 x + 500 ) = − 10 x 2 + 710 x − 10500 L = (x - 21)(-10x + 500) = -10x^2 + 710x - 10500 L=(x−21)(−10x+500)=−10x2+710x−10500

该函数为二次函数,开口向下(二次项系数 − 10 < 0 -10 < 0 −10<0),顶点处取最大值。顶点横坐标为:

x = − b 2 a = − 710 2 × ( − 10 ) = 35.5 x = -\frac{b}{2a} = -\frac{710}{2 \times (-10)} = 35.5 x=−2ab=−2×(−10)710=35.5(在定义域 [ 21 , 50 ] [21, 50] [21,50] 内)。

代入得最大利润:

L = − 10 × 35. 5 2 + 710 × 35.5 − 10500 = 1080.5 L = -10 \times 35.5^2 + 710 \times 35.5 - 10500 = 1080.5 L=−10×35.52+710×35.5−10500=1080.5 元。

三、推广简化模型法的关键原则

- “简化” 不 “失真”:简化后的模型必须保留原问题的 核心逻辑(如行程问题的 “路程 = 速度 × 时间”、利润问题的 “利润 = 收入 - 成本”),否则简化结果无法迁移到原问题。

- “分步” 不 “跳跃”:叠加复杂条件时,每次只加一个(如立体几何中先解决 “静态点”,再解决 “动态点”),避免因同时引入多个变量导致思路混乱。

- “通用” 不 “特殊”:从简化模型中提炼的方法,需脱离 “特殊条件” 限制(如从 “具体函数 f ( x ) = x f(x) = x f(x)=x” 提炼的 “定义法判断单调性”,可适用于抽象函数)。

- “验证” 不 “默认”:还原原问题后,需验证解法的合理性(如概率问题中检查 “对立事件是否完整”、几何问题中检查 “展开面是否正确”、应用题中检查 “变量定义域是否符合实际意义”)。

通过以上框架和策略,可将简化模型法从单一问题推广到几乎所有数学领域——本质是通过 “拆解 - 简化 - 解决 - 还原” 的闭环,将 “复杂的未知问题” 转化为 “简单的已知问题”,再逐步攻克难点,最终形成系统化的解题思路。

via:

-

soft question - What are good “math habits” that have improved your mathematical practice?

https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/2237243/what-are-good-math-habits-that-have-improved-your-mathematical-practice -

……

168万+

168万+

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?