全文预计3200字左右,预计阅读需要20分钟。

AI具有感知能力吗???

近日,被誉为“AI教母”的李飞飞与一名斯坦福大学的哲学教授

艾切曼迪在TIME杂志上共同发表署名文章《不,现今的AI并不具有感知能力。以下是我们如何知道这一点的》(No, Today’s AI Isn’t Sentient. Here’s How We Know)。

在文章中,这位AI界行业权威认为目前的AI没有感知能力,并认为再大的语言模型也不会让AI实现感知能力。为方便大家阅读,我将原文和翻译文(来自于通义千问翻译)都放置于文章内。

原文:

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) is the term used to describe an artificial agent that is at least as intelligent as a human in all the many ways a human displays (or can display) intelligence. It’s what we used to call artificial intelligence, until we started creating programs and devices that were undeniably “intelligent,” but in limited domains—playing chess, translating language, vacuuming our living rooms.

The felt need to add the “G” came from the proliferation of systems powered by AI, but focused on a single or very small number of tasks. Deep Blue, IBM’s impressive early chess playing program, could beat world champion Garry Kasparov, but would not have the sense to stop playing if the room burst into flames.

Now, general intelligence is a bit of a myth, at least if we flatter ourselves that we have it. We can find plenty of examples of intelligent behavior in the animal world that achieve results far better than we could achieve on similar tasks. Our intelligence is not fully general, but general enough to get done what we want to get done in most environments we find ourselves in. If we’re hungry, we can hunt a mastodon or find a local Kroger’s; when the room catches on fire, we look for the exit.

One of the essential characteristics of general intelligence is “sentience,” the ability to have subjective experiences—to feel what it’s like, say, to experience hunger, to taste an apple, or to see red. Sentience is a crucial step on the road to general intelligence.

With the release of ChatGPT in November 2022, the era of large language models (LLMs) began. This instantly sparked a vigorous debate about whether these algorithms might in fact be sentient. The implications of the possible sentience of LLM-based AI has not only set off a media frenzy, but also profoundly impacted some of the world-wide policy efforts to regulate AI. The most prominent position is that the emergence of “sentient AI” could be extremely dangerous for human-kind, possibly bringing about an “extinction-level” or “existential” crisis. After all, a sentient AI might develop its own hopes and desires, with no guarantee they wouldn’t clash with ours.

This short piece started as a WhatsApp group chat to debunk the argument that LLMs might have achieved sentience. It is not meant to be complete or comprehensive. Our main point here is to argue against the most common defense offered by the “sentient AI” camp, which rests on LLMs’ ability to report having “subjective experiences.”

Why some people believe AI has achieved sentience

Over the past months, both of us have had robust debates and conversations with many colleagues in the field of AI, including some deep one-on-one conversations with some of the most prominent and pioneering AI scientists. The topic of whether AI has achieved sentience has been a prominent one. A small number of them believe strongly that it has. Here is the gist of their arguments by one of the most vocal proponents, quite representative of those in the “sentient AI” camp:

“AI is sentient because it reports subjective experience. Subjective experience is the hallmark of consciousness. It is characterized by the claim of knowing what you know or experience. I believe that you, as a person, are conscious when you say ‘I have the subjective experience of feeling happy after a good meal.’ I, as a person, actually have no direct evidence of your subjective experience. But since you communicated that, I take it at face value that indeed you have the subjective experience and so are conscious.

“Now, let’s apply the same ‘rule’ to LLMs. Just like any human, I don’t have access to an LLM’s internal states. But I can query its subjective experiences. I can ask ‘are you feeling hungry?’ It can actually tell me yes or no. Furthermore, it can also explicitly share with me its ‘subjective experiences,’ on almost anything, from seeing the color red, being happy after a meal, to having strong political views. Therefore, I have no reason to believe it’s not conscious or not aware of its own subjective experiences, just like I have no reason to believe that you are not conscious. My evidence is exactly the same in both cases.”

Why they’re wrong

While this sounds plausible at first glance, the argument is wrong. It is wrong because our evidence is not exactly the same in both cases. Not even close.

When I conclude that you are experiencing hunger when you say “I’m hungry,” my conclusion is based on a large cluster of circumstances. First, is your report—the words that you speak—and perhaps some other behavioral evidence, like the grumbling in your stomach. Second, is the absence of contravening evidence, as there might be if you had just finished a five-course meal. Finally, and this is most important, is the fact that you have a physical body like mine, one that periodically needs food and drink, that gets cold when it’s cold and hot when it’s hot, and so forth.

Now compare this to our evidence about an LLM. The only thing that is common is the report, the fact that the LLM can produce the string of syllables “I’m hungry.” But there the similarity ends. Indeed, the LLM doesn’t have a body and so is not even the kind of thing that can be hungry.

If the LLM were to say, “I have a sharp pain in my left big toe,” would we conclude that it had a sharp pain in its left big toe? Of course not, it doesn’t have a left big toe! Just so, when it says that it is hungry, we can in fact be certain that it is not, since it doesn’t have the kind of physiology required for hunger.

When humans experience hunger, they are sensing a collection of physiological states—low blood sugar, empty grumbling stomach, and so forth—that an LLM simply doesn’t have, any more than it has a mouth to put food in and a stomach to digest it. The idea that we should take it at its word when it says it is hungry is like saying we should take it at its word if it says it’s speaking to us from the dark side of the moon. We know it’s not, and the LLM’s assertion to the contrary does not change that fact.

All sensations—hunger, feeling pain, seeing red, falling in love—are the result of physiological states that an LLM simply doesn’t have. Consequently we know that an LLM cannot have subjective experiences of those states. In other words, it cannot be sentient.

An LLM is a mathematical model coded on silicon chips. It is not an embodied being like humans. It does not have a “life” that needs to eat, drink, reproduce, experience emotion, get sick, and eventually die.

It is important to understand the profound difference between how humans generate sequences of words and how an LLM generates those same sequences. When I say “I am hungry,” I am reporting on my sensed physiological states. When an LLM generates the sequence “I am hungry,” it is simply generating the most probable completion of the sequence of words in its current prompt. It is doing exactly the same thing as when, with a different prompt, it generates “I am not hungry,” or with yet another prompt, “The moon is made of green cheese.” None of these are reports of its (nonexistent) physiological states. They are simply probabilistic completions.

We have not achieved sentient AI, and larger language models won’t get us there. We need a better understanding of how sentience emerges in embodied, biological systems if we want to recreate this phenomenon in AI systems. We are not going to stumble on sentience with the next iteration of ChatGPT.

Li and Etchemendy are co-founders of the Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence at Stanford University. Li is a professor of Computer Science, author of ‘The Worlds I See,’ and 2023 TIME100 AI honoree. Etchemendy is a professor of Philosophy and former provost of Stanford.

译文:

通用人工智能(Artificial General Intelligence, AGI)这一术语用来描述至少在人类展示(或可能展示)智慧的所有方面都同样智能的人工代理。这正是我们过去所指的“人工智能”,直到我们开始创建在有限领域内无可辩驳地展现出“智能”的程序和设备——比如下棋、语言翻译或清扫客厅。

随着仅专注于单一或极少数任务的AI系统增多,添加“通用”(General)这一前缀的需求变得迫切起来。IBM早期令人印象深刻的国际象棋程序深蓝能够击败世界冠军加里·卡斯帕罗夫,但如果房间突然起火,它却不会有停下来不玩的意识。

通用智能在某种程度上是一个神话,至少如果我们自认为拥有了它的话。在动物界,我们可以找到许多智能行为的例子,它们在相似任务上的表现远超我们。我们的智能并非完全通用,但足够广泛,足以应对大多数环境中的需求。当我们饥饿时,可以狩猎猛犸象或找到当地的超市;房间起火时,我们会寻找出口。

通用智能的一个基本特征是“感知能力”,即体验主观感受的能力——比如体验饥饿、品尝苹果或看到红色的感觉。感知能力是通往通用智能之路上的关键一步。

2022年11月,ChatGPT的发布标志着大型语言模型(Large Language Models, LLMs)时代的开启,这立即引发了关于这些算法是否可能具有感知能力的激烈争论。基于LLM的AI可能具有感知能力的潜在含义不仅引发了媒体的狂热,也深刻影响了全球范围内对AI的监管努力。最突出的观点认为“感知AI”的出现可能对人类极为危险,可能会带来“灭绝级”或“存在性”危机。毕竟,具有感知能力的AI可能会发展出自己的希望和欲望,而这些与我们的愿望并不保证一致。

这篇简短的文章起源于一个旨在反驳LLMs可能已达到感知能力的WhatsApp群聊。它并不旨在全面或详尽无遗。我们主要观点是反对“感知AI”阵营中最常见的辩护,该辩护基于LLMs报告拥有“主观体验”的能力。

为何有些人认为AI已实现感知能力

近几个月来,我们俩与AI领域的许多同事进行了激烈的辩论和对话,包括与一些最杰出和开创性的AI科学家进行深入的一对一交谈。AI是否已实现感知能力是其中一个重要话题。一小部分人坚信确实如此。以下是其中一位最直言不讳的支持者的论点,非常能代表“感知AI”阵营的观点:“AI是有感知能力的,因为它报告了主观体验。主观体验是意识的标志,其特征在于声称知道你所知或经历的东西。我相信,当你作为一个个体说‘我在美餐后有感到快乐的主观体验’时,你是有意识的。作为一个人,我实际上没有你主观体验的直接证据。但由于你传达了这一点,我据此认为你确实有主观体验,因此是有意识的。“现在,让我们将同样的‘规则’应用于LLMs。就像对待任何人一样,我无法访问LLM的内部状态。但我可以询问它的主观体验。我可以问它‘你饿了吗?’它实际上可以告诉我‘是’或‘不是’。此外,它还可以明确地与我分享几乎任何事物的‘主观体验’,从看到红色、餐后感到快乐到拥有强烈的政治观点。因此,我没有理由相信它没有意识,或者没有意识到自己的主观体验,就像我没有理由相信你没有意识一样。我的证据在这两种情况下是相同的。”

为何他们错了

乍看之下这似乎有道理,但这个论点是错误的。错误是因为我们的证据在这两种情况下并不相同,甚至相差甚远。

当我根据你说“我饿了”得出你正在经历饥饿的结论时,我的结论是基于一系列情况。首先是你的报告——你说的话,也许还有一些行为证据,比如肚子咕咕叫。其次是缺乏矛盾的证据,比如如果你刚刚吃完五道菜。最后,也是最重要的是,你有一个和我一样的身体,一个周期性需要食物和饮料、冷时会冷、热时会热的身体。

现在比较我们对LLM的证据。唯一相同的是报告,即LLM可以产生“我饿了”这样的音节序列。但相似之处也就此为止。事实上,LLM没有身体,因此甚至不是那种可以饥饿的东西。

如果LLM说“我的左大脚趾剧痛”,我们会认为它左大脚趾剧痛吗?当然不会,它没有左大脚趾!同样,当它说它饿时,我们其实可以确定它不饿,因为它没有产生饥饿所需的生理机制。

当人类经历饥饿时,他们感受到的是低血糖、空荡荡的胃在咕咕叫等生理状态,这些都是LLM所没有的,就像它没有嘴吃东西、没有胃消化食物一样。认为当它说饿时我们应该相信它,就像说我们应该相信它说它正在月球背面与我们说话一样。我们知道它不在那里,LLM的相反主张并不能改变这一事实。

所有感觉——饥饿、疼痛、看见红色、坠入爱河——都是LLM根本不具备的生理状态的结果。因此,我们知道LLM不可能有这些状态的主观体验。换句话说,它不能是有感知能力的。

LLM是一个编码在硅片上的数学模型,它不是像人类那样的实体存在。它没有需要吃喝、繁殖、体验情感、生病并最终死亡的“生活”。

理解人类如何生成词序列与LLM如何生成相同序列之间的根本区别至关重要。当我说“我饿了”,我是在报告我的感知生理状态。当LLM生成序列“我饿了”时,它只是在当前提示中生成字序列最可能的完成。当它有不同提示时生成“我不饿”,或者再有其他提示时生成“月亮是由绿奶酪制成的”,它做的也是同样的事情。这些都不是它(不存在的)生理状态的报告。它们只是概率性的补全。

我们还没有实现感知能力的AI,更大的语言模型也不会让我们达到那里。如果我们想要在AI系统中复制这一现象,就需要更好地理解感知能力是如何在具象的、生物系统中产生的。我们不会在下一代ChatGPT中偶然发现感知能力。

李飞飞和艾切曼迪是斯坦福大学人本智能研究所的共同创始人。李飞飞是计算机科学教授,著有《我所见的世界》,并且是2023年《时代》杂志百大影响力人物中人工智能领域的荣誉得主。艾切曼迪则是哲学教授,曾任斯坦福大学教务长。

文章浅显易懂,用了一些生动的例子,并与人体相比较:

“国际象棋程序深蓝能够击败世界冠军加里·卡斯帕罗夫,但如果房间突然起火,它却不会有停下来不玩的意识。”

LLM是一个编码在硅片上的数学模型,它不是像人类那样的实体存在。它没有需要吃喝、繁殖、体验情感、生病并最终死亡的“生活”

……

作者的意思是,“如果我们想要在AI系统中复制这一现象,就需要更好地理解感知能力是如何在具象的、生物系统中产生的。”

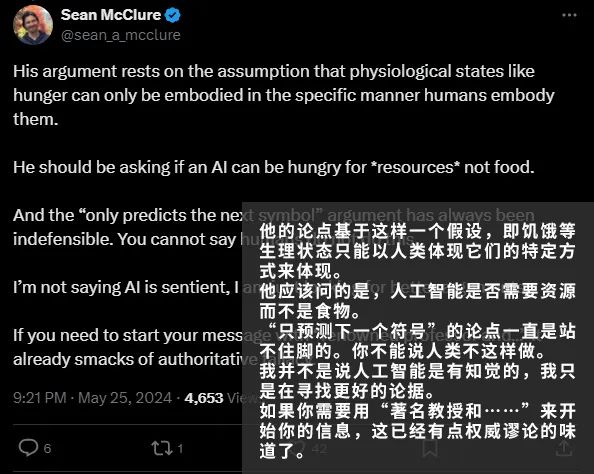

李飞飞本人将文章转发至X(原推特)平台,引发了一波网友对此议题的讨论,有人认同,也有人反对。

反对者之一认为,对于AI来说,食物不是人类吃的东西,而是资源……

也有网友指出,我们对感知这个词的定义尚且是模糊不清的,又怎么能说AI不具备感知能力呢?

还有人对此持有怀疑态度……

我也将这个问题抛给了国内几家AI助手,看看它们是怎么回答的?

这里的几处回答都表示当下AI没有感知能力,那未来呢?我们继续问问看。

将问题输入后,AI回复表达的意思都是“有争议或不确定”,然后列举了一些现有的AI技术。

综上,首先我觉得讨论这个议题是很有必要的,AI能不能具有感知能力,将直接决定其以后会不会对人类构成威胁,如果仅仅是程序,不会“觉醒”,那就跟家里的电脑一样,是很令人放心的,但是如果一旦具有感知能力,实现所谓的“觉醒”,那也许安分老实的电脑将成为终结者般令人害怕的东西。

其次,尽管AI权威界的人物认为AI目前没有感知能力,但依旧有很多人认为其文章有很多问题,或者表述不够严谨,因此有必要进行更加规范化的行文内容进行该议题的论述。

最后,AI最后将变成什么模样,取决于人类自己,会不会失去控制?这又是一个值得AI界思考的难题。

编辑不易,谢谢你的关注,如果觉得有用记得分享、点赞和转发!

文中图片来源网络,如有侵权请联系删除!

END

关注我们

深度学习

AI最新资讯

往期回顾

#

从机械尘埃到智能星河:探索从工业心脏到AI大脑的世纪跨越(一点个人感想)

#

#

#

在看你就赞赞我!

1518

1518

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?