GC,Garbage Collect,中文意思就是垃圾回收,指的是系统中的内存的分配和回收管理。其对系统性能的影响是不可小觑的。今天就来讲一下关于GC优化的东西,这里并不着重说概念和理论,主要说一些实用的东西。关于概念和理论这里只作简单说明,具体的你们能够看微软官方文档。程序员

1、什么是GC 算法

GC如其名,就是垃圾收集,固然这里仅就内存而言。Garbage Collector(垃圾收集器,在不至于混淆的状况下也成为GC)以应用程序的root为基础,遍历应用程序在Heap上动态分配的全部对象[2],经过识别它们是否被引用来肯定哪些对象是已经死亡的、哪些仍须要被使用。已经再也不被应用程序的root或者别的对象所引用的对象就是已经死亡的对象,即所谓的垃圾,须要被回收。这就是GC工做的原理。为了实现这个原理,GC有多种算法。比较常见的算法有Reference Counting,Mark Sweep,Copy Collection等等。目前主流的虚拟系统.NET CLR,Java VM和Rotor都是采用的Mark Sweep算法。(此段内容来自网络)数据库

.NET的GC机制有这样两个问题:网络

首先,GC并非能释放全部的资源。它不能自动释放非托管资源。函数

第二,GC并非实时性的,这将会形成系统性能上的瓶颈和不肯定性。性能

GC并非实时性的,这会形成系统性能上的瓶颈和不肯定性。因此有了IDisposable接口,IDisposable接口定义了Dispose方法,这个方法用来供程序员显式调用以释放非托管资源。使用using语句能够简化资源管理。优化

2、托管资源和非托管资源 ui

托管资源指的是.NET能够自动进行回收的资源,主要是指托管堆上分配的内存资源。托管资源的回收工做是不须要人工干预的,有.NET运行库在合适调用垃圾回收器进行回收。this

非托管资源指的是.NET不知道如何回收的资源,最多见的一类非托管资源是包装操做系统资源的对象,例如文件,窗口,网络链接,数据库链接,画刷,图标等。这类资源,垃圾回收器在清理的时候会调用Object.Finalize()方法。默认状况下,方法是空的,对于非托管对象,须要在此方法中编写回收非托管资源的代码,以便垃圾回收器正确回收资源。spa

在.NET中,Object.Finalize()方法是没法重载的,编译器是根据类的析构函数来自动生成Object.Finalize()方法的,因此对于包含非托管资源的类,能够将释放非托管资源的代码放在析构函数。

3、关于GC优化的一个例子

正常状况下,咱们是不须要去管GC这些东西的,然而GC并非实时性的,因此咱们的资源使用完后,GC何时回收也是不肯定的,因此会带来一些诸如内存泄漏、内存不足的状况,好比咱们处理一个约500M的大文件,用完后GC不会马上执行清理来释放内存,由于GC不知道咱们是否还会使用,因此它就等待,先去处理其余的东西,过一段时间后,发现这些东西再也不用了,才执行清理,释放内存。

下面,来介绍一下GC中用到的几个函数:

GC.SuppressFinalize(this); //请求公共语言运行时不要调用指定对象的终结器。

GC.GetTotalMemory(false); //检索当前认为要分配的字节数。 一个参数,指示此方法是否能够等待较短间隔再返回,以便系统回收垃圾和终结对象。

GC.Collect(); //强制对全部代进行即时垃圾回收。

GC运行机制

写代码前,咱们先来讲一下GC的运行机制。你们都知道GC是一个后台线程,他会周期性的查找对象,而后调用Finalize()方法去消耗他,咱们继承IDispose接口,调用Dispose方法,销毁了对象,而GC并不知道。GC依然会调用Finalize()方法,而在.NET 中Object.Finalize()方法是没法重载的,因此咱们可使用析构函数来阻止重复的释放。咱们调用完Dispose方法后,还有调用GC.SuppressFinalize(this) 方法来告诉GC,不须要在调用这些对象的Finalize()方法了。

下面,咱们新建一个控制台程序,加一个Factory类,让他继承自IDispose接口,代码以下:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

namespace GarbageCollect

{

public class Factory : IDisposable

{

private StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder();

List<int> list = new List<int>();

//拼接字符串,创造一些内存垃圾

public void MakeSomeGarbage()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 50000; i++)

{

sb.Append(i.ToString());

}

}

//销毁类时,会调用析构函数

~Factory()

{

Dispose(false);

}

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

}

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (!disposing)

{

return;

}

sb = null;

GC.Collect();

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

}

}

只有继承自IDispose接口,使用这个类时才能使用Using语句,在main方法中写以下代码:

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Diagnostics;

namespace GarbageCollect

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

using(Factory f = new Factory())

{

f.MakeSomeGarbage();

Console.WriteLine("Total memory is {0} KBs.", GC.GetTotalMemory(false) / 1024);

}

Console.WriteLine("After GC total memory is {0} KBs.", GC.GetTotalMemory(false) / 1024);

Console.Read();

}

}

}

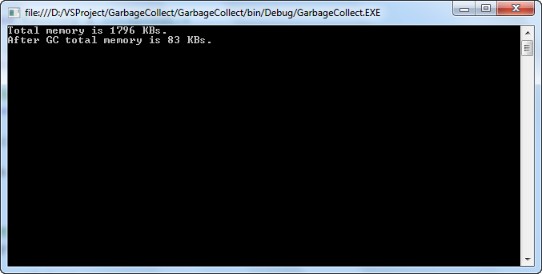

运行结果以下,能够看到资源运行MakeSomeGarbage()函数后的内存占用为1796KB,释放后成了83Kb.

代码运行机制:

咱们写了Dispose方法,还写了析构函数,那么他们分别何时被调用呢?咱们分别在两个方法上面下断点。调试运行,你会发现先走到了Dispose方法上面,知道程序运行完也没走析构函数,那是由于咱们调用了GC.SuppressFinalize(this)方法,若是去掉这个方法后,你会发现先走Dispose方法,后面又走析构函数。因此,咱们能够得知,若是咱们调用Dispose方法,GC就会调用析构函数去销毁对象,从而释放资源。

4、何时该调用GC.Collect

这里为了让你们看到效果,我显示调用的GC.Collect()方法,让GC马上释放内存,可是频繁的调用GC.Collect()方法会下降程序的性能,除非咱们程序中某些操做占用了大量内存须要立刻释放,才能够显示调用。下面是官方文档中的说明:

垃圾回收 GC 类提供 GC.Collect 方法,您可使用该方法让应用程序在必定程度上直接控制垃圾回收器。一般状况下,您应该避免调用任何回收方法,让垃圾回收器独立运行。在大多数状况下,垃圾回收器在肯定执行回收的最佳时机方面更有优点。可是,在某些不常发生的状况下,强制回收能够提升应用程序的性能。当应用程序代码中某个肯定的点上使用的内存量大量减小时,在这种状况下使用 GC.Collect 方法可能比较合适。例如,应用程序可能使用引用大量非托管资源的文档。当您的应用程序关闭该文档时,您彻底知道已经再也不须要文档曾使用的资源了。出于性能的缘由,一次所有释放这些资源颇有意义。有关更多信息,请参见 GC.Collect 方法。

在垃圾回收器执行回收以前,它会挂起当前正在执行的全部线程。若是没必要要地屡次调用 GC.Collect,这可能会形成性能问题。您还应该注意不要将调用GC.Collect 的代码放置在程序中用户能够常常调用的点上。这可能会削弱垃圾回收器中优化引擎的做用,而垃圾回收器能够肯定运行垃圾回收的最佳时间。

///////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Proper use of the IDisposable interface

I know from reading the Microsoft documentation that the "primary" use of the IDisposable interface is to clean up unmanaged resources.

To me, "unmanaged" means things like database connections, sockets, window handles, etc. But, I've seen code where the Dispose() method is implemented to free managed resources, which seems redundant to me, since the garbage collector should take care of that for you.

For example:

public class MyCollection : IDisposable

{

private List<String> _theList = new List<String>();

private Dictionary<String, Point> _theDict = new Dictionary<String, Point>();

// Die, clear it up! (free unmanaged resources)

public void Dispose()

{

_theList.clear();

_theDict.clear();

_theList = null;

_theDict = null;

}My question is, does this make the garbage collector free memory used by MyCollection any faster than it normally would?

edit: So far people have posted some good examples of using IDisposable to clean up unmanaged resources such as database connections and bitmaps. But suppose that _theList in the above code contained a million strings, and you wanted to free that memory now, rather than waiting for the garbage collector. Would the above code accomplish that?

I like the accepted answer because it tell you the correct 'pattern' of using IDisposable, but like the OP said in his edit, it does not answer his intended question. IDisposable does not 'call' the GC, it just 'marks' an object as destroyable. But what is the real way to free memory 'right now' instead of waiting for GC to kick in? I think this question deserves more discussion.

IDisposable doesn't mark anything. The Dispose method does what it has to do to clean up resources used by the instance. This has nothing to do with GC.

I do understand IDisposable. And which is why I said that the accepted answer does not answer the OP's intended question(and follow-up edit) about whether IDisposable will help in <i>freeing memory</i>. Since IDisposable has nothing to do with freeing memory, only resources, then like you said, there is no need to set the managed references to null at all which is what OP was doing in his example. So, the correct answer to his question is "No, it does not help free memory any faster. In fact, it does not help free memory at all, only resources". But anyway, thanks for your input.

if this is the case, then you should not have said "IDisposable does not 'call' the GC, it just 'marks' an object as destroyable"

There is no guaranteed way of freeing memory deterministically. You could call GC.Collect(), but that is a polite request, not a demand. All running threads must be suspended for garbage collection to proceed - read up on the concept of .NET safepoints if you want to learn more, e.g. msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/678ysw69(v=vs.110).aspx . If a thread cannot be suspended, e.g. because there's a call into unmanaged code, GC.Collect() may do nothing at all.

The point of Dispose is to free unmanaged resources. It needs to be done at some point, otherwise they will never be cleaned up. The garbage collector doesn't know how to call DeleteHandle() on a variable of type IntPtr, it doesn't know whether or not it needs to call DeleteHandle().

Note: What is an unmanaged resource? If you found it in the Microsoft .NET Framework: it's managed. If you went poking around MSDN yourself, it's unmanaged. Anything you've used P/Invoke calls to get outside of the nice comfy world of everything available to you in the .NET Framework is unmanaged – and you're now responsible for cleaning it up.

The object that you've created needs to expose some method, that the outside world can call, in order to clean up unmanaged resources. The method can be named whatever you like:

public void Cleanup()

or

public void Shutdown()

But instead there is a standardized name for this method:

public void Dispose()

There was even an interface created, IDisposable, that has just that one method:

public interface IDisposable

{

void Dispose()

}

So you make your object expose the IDisposable interface, and that way you promise that you've written that single method to clean up your unmanaged resources:

public void Dispose()

{

Win32.DestroyHandle(this.CursorFileBitmapIconServiceHandle);

}

And you're done. Except you can do better.

What if your object has allocated a 250MB System.Drawing.Bitmap (i.e. the .NET managed Bitmap class) as some sort of frame buffer? Sure, this is a managed .NET object, and the garbage collector will free it. But do you really want to leave 250MB of memory just sitting there – waiting for the garbage collector to eventually come along and free it? What if there's an open database connection? Surely we don't want that connection sitting open, waiting for the GC to finalize the object.

If the user has called Dispose() (meaning they no longer plan to use the object) why not get rid of those wasteful bitmaps and database connections?

So now we will:

- get rid of unmanaged resources (because we have to), and

- get rid of managed resources (because we want to be helpful)

So let's update our Dispose() method to get rid of those managed objects:

public void Dispose()

{

//Free unmanaged resources

Win32.DestroyHandle(this.CursorFileBitmapIconServiceHandle);

//Free managed resources too

if (this.databaseConnection != null)

{

this.databaseConnection.Dispose();

this.databaseConnection = null;

}

if (this.frameBufferImage != null)

{

this.frameBufferImage.Dispose();

this.frameBufferImage = null;

}

}

And all is good, except you can do better!

What if the person forgot to call Dispose() on your object? Then they would leak some unmanaged resources!

Note: They won't leak managed resources, because eventually the garbage collector is going to run, on a background thread, and free the memory associated with any unused objects. This will include your object, and any managed objects you use (e.g. the

Bitmapand theDbConnection).

If the person forgot to call Dispose(), we can still save their bacon! We still have a way to call it for them: when the garbage collector finally gets around to freeing (i.e. finalizing) our object.

Note: The garbage collector will eventually free all managed objects. When it does, it calls the

Finalizemethod on the object. The GC doesn't know, or care, about your Dispose method. That was just a name we chose for a method we call when we want to get rid of unmanaged stuff.

The destruction of our object by the Garbage collector is the perfect time to free those pesky unmanaged resources. We do this by overriding the Finalize() method.

Note: In C#, you don't explicitly override the

Finalize()method. You write a method that looks like a C++ destructor, and the compiler takes that to be your implementation of theFinalize()method:

~MyObject()

{

//we're being finalized (i.e. destroyed), call Dispose in case the user forgot to

Dispose(); //<--Warning: subtle bug! Keep reading!

}

But there's a bug in that code. You see, the garbage collector runs on a background thread; you don't know the order in which two objects are destroyed. It is entirely possible that in your Dispose() code, the managed object you're trying to get rid of (because you wanted to be helpful) is no longer there:

public void Dispose()

{

//Free unmanaged resources

Win32.DestroyHandle(this.gdiCursorBitmapStreamFileHandle);

//Free managed resources too

if (this.databaseConnection != null)

{

this.databaseConnection.Dispose(); //<-- crash, GC already destroyed it

this.databaseConnection = null;

}

if (this.frameBufferImage != null)

{

this.frameBufferImage.Dispose(); //<-- crash, GC already destroyed it

this.frameBufferImage = null;

}

}

So what you need is a way for Finalize() to tell Dispose() that it should not touch any managed resources (because they might not be there anymore), while still freeing unmanaged resources.

The standard pattern to do this is to have Finalize() and Dispose() both call a third(!) method; where you pass a Boolean saying if you're calling it from Dispose() (as opposed to Finalize()), meaning it's safe to free managed resources.

This internal method could be given some arbitrary name like "CoreDispose", or "MyInternalDispose", but is tradition to call it Dispose(Boolean):

protected void Dispose(Boolean disposing)

But a more helpful parameter name might be:

protected void Dispose(Boolean itIsSafeToAlsoFreeManagedObjects)

{

//Free unmanaged resources

Win32.DestroyHandle(this.CursorFileBitmapIconServiceHandle);

//Free managed resources too, but only if I'm being called from Dispose

//(If I'm being called from Finalize then the objects might not exist

//anymore

if (itIsSafeToAlsoFreeManagedObjects)

{

if (this.databaseConnection != null)

{

this.databaseConnection.Dispose();

this.databaseConnection = null;

}

if (this.frameBufferImage != null)

{

this.frameBufferImage.Dispose();

this.frameBufferImage = null;

}

}

}

And you change your implementation of the IDisposable.Dispose() method to:

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true); //I am calling you from Dispose, it's safe

}

and your finalizer to:

~MyObject()

{

Dispose(false); //I am *not* calling you from Dispose, it's *not* safe

}

Note: If your object descends from an object that implements

Dispose, then don't forget to call their base Dispose method when you override Dispose:

public override void Dispose()

{

try

{

Dispose(true); //true: safe to free managed resources

}

finally

{

base.Dispose();

}

}

And all is good, except you can do better!

If the user calls Dispose() on your object, then everything has been cleaned up. Later on, when the garbage collector comes along and calls Finalize, it will then call Dispose again.

Not only is this wasteful, but if your object has junk references to objects you already disposed of from the last call to Dispose(), you'll try to dispose them again!

You'll notice in my code I was careful to remove references to objects that I've disposed, so I don't try to call Dispose on a junk object reference. But that didn't stop a subtle bug from creeping in.

When the user calls Dispose(): the handle CursorFileBitmapIconServiceHandle is destroyed. Later when the garbage collector runs, it will try to destroy the same handle again.

protected void Dispose(Boolean iAmBeingCalledFromDisposeAndNotFinalize)

{

//Free unmanaged resources

Win32.DestroyHandle(this.CursorFileBitmapIconServiceHandle); //<--double destroy

...

}

The way you fix this is tell the garbage collector that it doesn't need to bother finalizing the object – its resources have already been cleaned up, and no more work is needed. You do this by calling GC.SuppressFinalize() in the Dispose() method:

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true); //I am calling you from Dispose, it's safe

GC.SuppressFinalize(this); //Hey, GC: don't bother calling finalize later

}

Now that the user has called Dispose(), we have:

- freed unmanaged resources

- freed managed resources

There's no point in the GC running the finalizer – everything's taken care of.

Couldn't I use Finalize to cleanup unmanaged resources?

The documentation for Object.Finalize says:

The Finalize method is used to perform cleanup operations on unmanaged resources held by the current object before the object is destroyed.

But the MSDN documentation also says, for IDisposable.Dispose:

Performs application-defined tasks associated with freeing, releasing, or resetting unmanaged resources.

So which is it? Which one is the place for me to cleanup unmanaged resources? The answer is:

It's your choice! But choose

Dispose.

You certainly could place your unmanaged cleanup in the finalizer:

~MyObject()

{

//Free unmanaged resources

Win32.DestroyHandle(this.CursorFileBitmapIconServiceHandle);

//A C# destructor automatically calls the destructor of its base class.

}

The problem with that is you have no idea when the garbage collector will get around to finalizing your object. Your un-managed, un-needed, un-used native resources will stick around until the garbage collector eventually runs. Then it will call your finalizer method; cleaning up unmanaged resources. The documentation of Object.Finalize points this out:

The exact time when the finalizer executes is undefined. To ensure deterministic release of resources for instances of your class, implement a Close method or provide a IDisposable.Dispose implementation.

This is the virtue of using Dispose to cleanup unmanaged resources; you get to know, and control, when unmanaged resource are cleaned up. Their destruction is "deterministic".

To answer your original question: Why not release memory now, rather than for when the GC decides to do it? I have a facial recognition software that needs to get rid of 530 MB of internal images now, since they're no longer needed. When we don't: the machine grinds to a swapping halt.

Bonus Reading

For anyone who likes the style of this answer (explaining the why, so the how becomes obvious), I suggest you read Chapter One of Don Box's Essential COM:

- Direct link: Chapter 1 sample by Pearson Publishing

- magnet: 84bf0b960936d677190a2be355858e80ef7542c0

In 35 pages he explains the problems of using binary objects, and invents COM before your eyes. Once you realize the why of COM, the remaining 300 pages are obvious, and just detail Microsoft's implementation.

I think every programmer who has ever dealt with objects or COM should, at the very least, read the first chapter. It is the best explanation of anything ever.

Extra Bonus Reading

When everything you know is wrong archiveby Eric Lippert

It is therefore very difficult indeed to write a correct finalizer, and the best advice I can give you is to not try.

This is a great answer but I think it would however benefit from a final code listing for a standard case and for a case where the the class derives from a baseclass that already implements Dispose. e.g having read here (msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa720161%28v=vs.71%29.aspx) as well I have got confused about what I should do when deriving from the class that already implements Dispose (hey I'm new to this).

What is the effect of setting the managed instances to null during the Dispose() call, other than ensuring that they won't be disposed again because the != null check would fail? What about managed types that are not Disposable? Should they be handled in the Dispose method at all (e.g. Set to null)? Should it be done for all managed objects, or only those that we consider 'heavy' and Worth the effort of doing anything before GC kicks in? I expect its only meant for Disposable members of a class, but system.Drawing.Image mentioned as example doesnt seem to be disposable...

You can set any variable you like to null inside your Dispose method. Setting a variable to null means it only might get collected sooner (since it has no outstanding references). If an object doesn't implement IDisposable, then you don't have to dispose of it. An object will only expose Dispose if it needs to be disposed of.

If you write correct code, you never need the finalizer/Dispose(bool) thingy." I'm not protecting against me; i'm protecing against the dozens, hundreds, thousands, or millions of other developers who might not get it right every time. Sometimes developers forget to call .Dispose. Sometimes you can't use using. We're following the .NET/WinRT approach of "the pit of success". We pay our developer taxes, and write better and defensive code to make it resilient to these problems.

"But you don't always have to write code for "the public"." But when trying to come up with best practices for a 2k+ upvoted answer, meant for general introduction to unmanaged memory, it's best to provide the best code samples possible. We don't want to leave it all out - and let people stumble into all this the hard way. Because that's the reality - thousands of developers each year learning this nuance about Disposing. No need to make it needlessly harder for them.

IDisposable is often used to exploit the using statement and take advantage of an easy way to do deterministic cleanup of managed objects.

public class LoggingContext : IDisposable {

public Finicky(string name) {

Log.Write("Entering Log Context {0}", name);

Log.Indent();

}

public void Dispose() {

Log.Outdent();

}

public static void Main() {

Log.Write("Some initial stuff.");

try {

using(new LoggingContext()) {

Log.Write("Some stuff inside the context.");

throw new Exception();

}

} catch {

Log.Write("Man, that was a heavy exception caught from inside a child logging context!");

} finally {

Log.Write("Some final stuff.");

}

}

}The purpose of the Dispose pattern is to provide a mechanism to clean up both managed and unmanaged resources and when that occurs depends on how the Dispose method is being called. In your example, the use of Dispose is not actually doing anything related to dispose, since clearing a list has no impact on that collection being disposed. Likewise, the calls to set the variables to null also have no impact on the GC.

You can take a look at this article for more details on how to implement the Dispose pattern, but it basically looks like this:

public class SimpleCleanup : IDisposable

{

// some fields that require cleanup

private SafeHandle handle;

private bool disposed = false; // to detect redundant calls

public SimpleCleanup()

{

this.handle = /*...*/;

}

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (!disposed)

{

if (disposing)

{

// Dispose managed resources.

if (handle != null)

{

handle.Dispose();

}

}

// Dispose unmanaged managed resources.

disposed = true;

}

}

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

}The method that is the most important here is the Dispose(bool), which actually runs under two different circumstances:

- disposing == true: the method has been called directly or indirectly by a user's code. Managed and unmanaged resources can be disposed.

- disposing == false: the method has been called by the runtime from inside the finalizer, and you should not reference other objects. Only unmanaged resources can be disposed.

The problem with simply letting the GC take care of doing the cleanup is that you have no real control over when the GC will run a collection cycle (you can call GC.Collect(), but you really shouldn't) so resources may stay around longer than needed. Remember, calling Dispose() doesn't actually cause a collection cycle or in any way cause the GC to collect/free the object; it simply provides the means to more deterministicly cleanup the resources used and tell the GC that this cleanup has already been performed.

The whole point of IDisposable and the dispose pattern isn't about immediately freeing memory. The only time a call to Dispose will actually even have a chance of immediately freeing memory is when it is handling the disposing == false scenario and manipulating unmanaged resources. For managed code, the memory won't actually be reclaimed until the GC runs a collection cycle, which you really have no control over (other than calling GC.Collect(), which I've already mentioned is not a good idea).

Your scenario isn't really valid since strings in .NET don't use any unamanged resources and don't implement IDisposable, there is no way to force them to be "cleaned up."

here should be no further calls to an object's methods after Dispose has been called on it (although an object should tolerate further calls to Dispose). Therefore the example in the question is silly. If Dispose is called, then the object itself can be discarded. So the user should just discard all references to that whole object (set them to null) and all the related objects internal to it will automatically get cleaned up.

As for the general question about managed/unmanaged and the discussion in other answers, I think any answer to this question has to start with a definition of an unmanaged resource.

What it boils down to is that there is a function you can call to put the system into a state, and there's another function you can call to bring it back out of that state. Now, in the typical example, the first one might be a function that returns a file handle, and the second one might be a call to CloseHandle.

But - and this is the key - they could be any matching pair of functions. One builds up a state, the other tears it down. If the state has been built but not torn down yet, then an instance of the resource exists. You have to arrange for the teardown to happen at the right time - the resource is not managed by the CLR. The only automatically managed resource type is memory. There are two kinds: the GC, and the stack. Value types are managed by the stack (or by hitching a ride inside reference types), and reference types are managed by the GC.

These functions may cause state changes that can be freely interleaved, or may need to be perfectly nested. The state changes may be threadsafe, or they might not.

Look at the example in Justice's question. Changes to the Log file's indentation must be perfectly nested, or it all goes wrong. Also they are unlikely to be threadsafe.

It is possible to hitch a ride with the garbage collector to get your unmanaged resources cleaned up. But only if the state change functions are threadsafe and two states can have lifetimes that overlap in any way. So Justice's example of a resource must NOT have a finalizer! It just wouldn't help anyone.

For those kinds of resources, you can just implement IDisposable, without a finalizer. The finalizer is absolutely optional - it has to be. This is glossed over or not even mentioned in many books.

You then have to use the using statement to have any chance of ensuring that Dispose is called. This is essentially like hitching a ride with the stack (so as finalizer is to the GC, using is to the stack).

The missing part is that you have to manually write Dispose and make it call onto your fields and your base class. C++/CLI programmers don't have to do that. The compiler writes it for them in most cases.

There is an alternative, which I prefer for states that nest perfectly and are not threadsafe (apart from anything else, avoiding IDisposable spares you the problem of having an argument with someone who can't resist adding a finalizer to every class that implements IDisposable).

Instead of writing a class, you write a function. The function accepts a delegate to call back to:

public static void Indented(this Log log, Action action)

{

log.Indent();

try

{

action();

}

finally

{

log.Outdent();

}

}And then a simple example would be:

Log.Write("Message at the top");

Log.Indented(() =>

{

Log.Write("And this is indented");

Log.Indented(() =>

{

Log.Write("This is even more indented");

});

});

Log.Write("Back at the outermost level again");The lambda being passed in serves as a code block, so it's like you make your own control structure to serve the same purpose as using, except that you no longer have any danger of the caller abusing it. There's no way they can fail to clean up the resource.

This technique is less useful if the resource is the kind that may have overlapping lifetimes, because then you want to be able to build resource A, then resource B, then kill resource A and then later kill resource B. You can't do that if you've forced the user to perfectly nest like this. But then you need to use IDisposable (but still without a finalizer, unless you have implemented threadsafety, which isn't free).

Scenarios I make use of IDisposable: clean up unmanaged resources, unsubscribe for events, close connections

The idiom I use for implementing IDisposable (not threadsafe):

class MyClass : IDisposable {

// ...

#region IDisposable Members and Helpers

private bool disposed = false;

public void Dispose() {

Dispose(true);

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

private void Dispose(bool disposing) {

if (!this.disposed) {

if (disposing) {

// cleanup code goes here

}

disposed = true;

}

}

~MyClass() {

Dispose(false);

}

#endregion

}This is almost the Microsoft Dispose pattern implementation except you've forgotten to make the DIspose(bool) virtual. The pattern itself is not a very good pattern and should be avoided unless you absolutely have to have dispose as part of an inheritance hierarchy.

If MyCollection is going to be garbage collected anyway, then you shouldn't need to dispose it. Doing so will just churn the CPU more than necessary, and may even invalidate some pre-calculated analysis that the garbage collector has already performed.

I use IDisposable to do things like ensure threads are disposed correctly, along with unmanaged resources.

EDIT In response to Scott's comment:

The only time the GC performance metrics are affected is when a call the [sic] GC.Collect() is made"

Conceptually, the GC maintains a view of the object reference graph, and all references to it from the stack frames of threads. This heap can be quite large and span many pages of memory. As an optimisation, the GC caches its analysis of pages that are unlikely to change very often to avoid rescanning the page unnecessarily. The GC receives notification from the kernel when data in a page changes, so it knows that the page is dirty and requires a rescan. If the collection is in Gen0 then it's likely that other things in the page are changing too, but this is less likely in Gen1 and Gen2. Anecdotally, these hooks were not available in Mac OS X for the team who ported the GC to Mac in order to get the Silverlight plug-in working on that platform.

Another point against unnecessary disposal of resources: imagine a situation where a process is unloading. Imagine also that the process has been running for some time. Chances are that many of that process's memory pages have been swapped to disk. At the very least they're no longer in L1 or L2 cache. In such a situation there is no point for an application that's unloading to swap all those data and code pages back into memory to 'release' resources that are going to be released by the operating system anyway when the process terminates. This applies to managed and even certain unmanaged resources. Only resources that keep non-background threads alive must be disposed, otherwise the process will remain alive.

Now, during normal execution there are ephemeral resources that must be cleaned up correctly (as @fezmonkey points out database connections, sockets, window handles) to avoid unmanaged memory leaks. These are the kinds of things that have to be disposed. If you create some class that owns a thread (and by owns I mean that it created it and therefore is responsible for ensuring it stops, at least by my coding style), then that class most likely must implement IDisposable and tear down the thread during Dispose.

The .NET framework uses the IDisposable interface as a signal, even warning, to developers that the this class must be disposed. I can't think of any types in the framework that implement IDisposable (excluding explicit interface implementations) where disposal is optional.

Calling Dispose is perfectly valid, legal, and encouraged. Objects that implement IDisposable usually do so for a reason. The only time the GC performance metrics are affected is when a call the GC.Collect() is made.

For many .net classes, disposal is "somewhat" optional, meaning that abandoning instances "usually" won't cause any trouble so long as one doesn't go crazy creating new instances and abandoning them. For example, the compiler-generated code for controls seems to create fonts when the controls are instantiated and abandon them when the forms are disposed; if one creates and disposes thousands of controls , this could tie up thousands of GDI handles, but in most cases controls aren't created and destroyed that much. Nonetheless, one should still try to avoid such abandonment.

In the case of fonts, I suspect the problem is that Microsoft never really defined what entity is responsible for disposing the "font" object assigned to a control; in some cases, a controls may share a font with a longer-lived object, so having the control Dispose the font would be bad. In other cases, a font will be assigned to a control and nowhere else, so if the control doesn't dispose it nobody will. Incidentally, this difficulty with fonts could have been avoided had there been a separate non-disposable FontTemplate class, since controls don't seem to use the GDI handle of their Font.

Yep, that code is completely redundant and unnecessary and it doesn't make the garbage collector do anything it wouldn't otherwise do (once an instance of MyCollection goes out of scope, that is.) Especially the .Clear() calls.

Answer to your edit: Sort of. If I do this:

public void WasteMemory()

{

var instance = new MyCollection(); // this one has no Dispose() method

instance.FillItWithAMillionStrings();

}

// 1 million strings are in memory, but marked for reclamation by the GCIt's functionally identical to this for purposes of memory management:

public void WasteMemory()

{

var instance = new MyCollection(); // this one has your Dispose()

instance.FillItWithAMillionStrings();

instance.Dispose();

}

// 1 million strings are in memory, but marked for reclamation by the GCIf you really really really need to free the memory this very instant, call GC.Collect(). There's no reason to do this here, though. The memory will be freed when it's needed.

re: "The memory will be freed when it's needed." Rather say, "when GC decides it's needed." You may see system performance issues before GC decides that memory is really needed. Freeing it up now may not be essential, but may be useful.

There are some corner cases in which nulling out references within a collection may expedite garbage collection of the items referred to thereby. For example, if a large array is created and filled with references to smaller newly-created items, but it isn't needed for very long after that, abandoning the array may cause those items to be kept around until the next Level 2 GC, while zeroing it out first may make the items eligible for the next level 0 or level 1 GC. To be sure, having big short-lived objects on the Large Object Heap is icky anyway (I dislike the design) but..

.zeroing out such arrays before abandoning them my sometimes lessen the GC impact.

In most cases nulling stuff is not required, but some objects may actually keep a bunch of other objects alive too, even when they aren't required anymore. Setting something like a reference to a Thread to null may be beneficial, but nowadays, probably not. Often the more complicated code if the big object could still be called upon in some method of checking if it has been nulled already isn't worth the performance gain. Prefer clean over "I think this is slightly faster".

In the example you posted, it still doesn't "free the memory now". All memory is garbage collected, but it may allow the memory to be collected in an earlier generation. You'd have to run some tests to be sure.

The Framework Design Guidelines are guidelines, and not rules. They tell you what the interface is primarily for, when to use it, how to use it, and when not to use it.

I once read code that was a simple RollBack() on failure utilizing IDisposable. The MiniTx class below would check a flag on Dispose() and if the Commit call never happened it would then call Rollback on itself. It added a layer of indirection making the calling code a lot easier to understand and maintain. The result looked something like:

using( MiniTx tx = new MiniTx() )

{

// code that might not work.

tx.Commit();

} I've also seen timing / logging code do the same thing. In this case the Dispose() method stopped the timer and logged that the block had exited.

using( LogTimer log = new LogTimer("MyCategory", "Some message") )

{

// code to time...

}So here are a couple of concrete examples that don't do any unmanaged resource cleanup, but do successfully used IDisposable to create cleaner code.

Take a look at @Daniel Earwicker's example using higher order functions. For benchmarking, timing, logging etc. It seems much more straightforward.

I won't repeat the usual stuff about Using or freeing un-managed resources, that has all been covered. But I would like to point out what seems a common misconception.

Given the following code

Public Class LargeStuff

Implements IDisposable

Private _Large as string()

'Some strange code that means _Large now contains several million long strings.

Public Sub Dispose() Implements IDisposable.Dispose

_Large=Nothing

End Sub

I realise that the Disposable implementation does not follow current guidelines, but hopefully you all get the idea.

Now, when Dispose is called, how much memory gets freed?

Answer: None.

Calling Dispose can release unmanaged resources, it CANNOT reclaim managed memory, only the GC can do that. Thats not to say that the above isn't a good idea, following the above pattern is still a good idea in fact. Once Dispose has been run, there is nothing stopping the GC re-claiming the memory that was being used by _Large, even though the instance of LargeStuff may still be in scope. The strings in _Large may also be in gen 0 but the instance of LargeStuff might be gen 2, so again, memory would be re-claimed sooner.

There is no point in adding a finaliser to call the Dispose method shown above though. That will just DELAY the re-claiming of memory to allow the finaliser to run.

If an instance of LargeStuff has been around long enough to make it to Generation 2, and if _Large holds a reference to a newly-created string which is in Generation 0, then if the the instance of LargeStuff is abandoned without nulling out _Large, then string referred to by _Large will be kept around until the next Gen2 collection. Zeroing out _Large may let the string get eliminated at the next Gen0 collection. In most cases, nulling out references is not helpful, but there are cases where it can offer some benefit.

If you want to delete right now, use unmanaged memory.

See:

Follow

If anything, I'd expect the code to be less efficient than when leaving it out.

Calling the Clear() methods are unnecessary, and the GC probably wouldn't do that if the Dispose didn't do it...

Apart from its primary use as a way to control the lifetime of system resources (completely covered by the awesome answer of Ian, kudos!), the IDisposable/using combo can also be used to scope the state change of (critical) global resources: the console, the threads, the process, any global object like an application instance.

I've written an article about this pattern: http://pragmateek.com/c-scope-your-global-state-changes-with-idisposable-and-the-using-statement/

It illustrates how you can protect some often used global state in a reusable and readable manner: console colors, current thread culture, Excel application object properties...

Your given code sample is not a good example for IDisposable usage. Dictionary clearing normally shouldn't go to the Dispose method. Dictionary items will be cleared and disposed when it goes out of scope. IDisposable implementation is required to free some memory/handlers that will not release/free even after they out of scope.

The following example shows a good example for IDisposable pattern with some code and comments.

public class DisposeExample

{

// A base class that implements IDisposable.

// By implementing IDisposable, you are announcing that

// instances of this type allocate scarce resources.

public class MyResource: IDisposable

{

// Pointer to an external unmanaged resource.

private IntPtr handle;

// Other managed resource this class uses.

private Component component = new Component();

// Track whether Dispose has been called.

private bool disposed = false;

// The class constructor.

public MyResource(IntPtr handle)

{

this.handle = handle;

}

// Implement IDisposable.

// Do not make this method virtual.

// A derived class should not be able to override this method.

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

// This object will be cleaned up by the Dispose method.

// Therefore, you should call GC.SupressFinalize to

// take this object off the finalization queue

// and prevent finalization code for this object

// from executing a second time.

GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

// Dispose(bool disposing) executes in two distinct scenarios.

// If disposing equals true, the method has been called directly

// or indirectly by a user's code. Managed and unmanaged resources

// can be disposed.

// If disposing equals false, the method has been called by the

// runtime from inside the finalizer and you should not reference

// other objects. Only unmanaged resources can be disposed.

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

// Check to see if Dispose has already been called.

if(!this.disposed)

{

// If disposing equals true, dispose all managed

// and unmanaged resources.

if(disposing)

{

// Dispose managed resources.

component.Dispose();

}

// Call the appropriate methods to clean up

// unmanaged resources here.

// If disposing is false,

// only the following code is executed.

CloseHandle(handle);

handle = IntPtr.Zero;

// Note disposing has been done.

disposed = true;

}

}

// Use interop to call the method necessary

// to clean up the unmanaged resource.

[System.Runtime.InteropServices.DllImport("Kernel32")]

private extern static Boolean CloseHandle(IntPtr handle);

// Use C# destructor syntax for finalization code.

// This destructor will run only if the Dispose method

// does not get called.

// It gives your base class the opportunity to finalize.

// Do not provide destructors in types derived from this class.

~MyResource()

{

// Do not re-create Dispose clean-up code here.

// Calling Dispose(false) is optimal in terms of

// readability and maintainability.

Dispose(false);

}

}

public static void Main()

{

// Insert code here to create

// and use the MyResource object.

}

}There are things that the Dispose() operation does in the example code that might have an effect that would not occur due to a normal GC of the MyCollection object.

If the objects referenced by _theList or _theDict are referred to by other objects, then that List<> or Dictionary<> object will not be subject to collection but will suddenly have no contents. If there were no Dispose() operation as in the example, those collections would still contain their contents.

Of course, if this were the situation I would call it a broken design - I'm just pointing out (pedantically, I suppose) that the Dispose() operation might not be completely redundant, depending on whether there are other uses of the List<> or Dictionary<> that are not shown in the fragment.

They're private fields, so I think it's fair to assume the OP isn't giving out references to them.

the code fragment is just example code, so I'm just pointing out that there may be a side-effect that is easy to overlook; 2) private fields are often the target of a getter property/method - maybe too much (getter/setters are considered by some people to be a bit of an anti-pattern).

One problem with most discussions of "unmanaged resources" is that they don't really define the term, but seem to imply that it has something to do with unmanaged code. While it is true that many types of unmanaged resources do interface with unmanaged code, thinking of unmanaged resources in such terms isn't helpful.

Instead, one should recognize what all managed resources have in common: they all entail an object asking some outside 'thing' to do something on its behalf, to the detriment of some other 'things', and the other entity agreeing to do so until further notice. If the object were to be abandoned and vanish without a trace, nothing would ever tell that outside 'thing' that it no longer needed to alter its behavior on behalf of the object that no longer existed; consequently, the 'thing's usefulness would be permanently diminished.

An unmanaged resource, then, represents an agreement by some outside 'thing' to alter its behavior on behalf of an object, which would useless impair the usefulness of that outside 'thing' if the object were abandoned and ceased to exist. A managed resource is an object which is the beneficiary of such an agreement, but which has signed up to receive notification if it is abandoned, and which will use such notification to put its affairs in order before it is destroyed.

Well, IMO, definition of unmanaged object is clear; any non-GC object.

Unmanaged Object != Unmanaged Resource. Things like events can be implemented entirely using managed objects, but still constitute unmanaged resources because--at least in the case of short-lived objects subscribing to long-lived-objects' events--the GC knows nothing about how to clean them up

IDisposable is good for unsubscribing from events.

First of definition. For me unmanaged resource means some class, which implements IDisposable interface or something created with usage of calls to dll. GC doesn't know how to deal with such objects. If class has for example only value types, then I don't consider this class as class with unmanaged resources. For my code I follow next practices:

- If created by me class uses some unmanaged resources then it means that I should also implement IDisposable interface in order to clean memory.

- Clean objects as soon as I finished usage of it.

- In my dispose method I iterate over all IDisposable members of class and call Dispose.

- In my Dispose method call GC.SuppressFinalize(this) in order to notify garbage collector that my object was already cleaned up. I do it because calling of GC is expensive operation.

- As additional precaution I try to make possible calling of Dispose() multiple times.

- Sometime I add private member _disposed and check in method calls did object was cleaned up. And if it was cleaned up then generate ObjectDisposedException

Following template demonstrates what I described in words as sample of code:

public class SomeClass : IDisposable

{

/// <summary>

/// As usually I don't care was object disposed or not

/// </summary>

public void SomeMethod()

{

if (_disposed)

throw new ObjectDisposedException("SomeClass instance been disposed");

}

public void Dispose()

{

Dispose(true);

}

private bool _disposed;

protected virtual void Dispose(bool disposing)

{

if (_disposed)

return;

if (disposing)//we are in the first call

{

}

_disposed = true;

}

}"For me unmanaged resource means some class, which implements IDisposable interface or something created with usage of calls to dll." So you are saying that any type which is IDisposable should itself be considered an unmanaged resource? That doesn't seem correct. Also if the implmenting type is a pure value type you seem to suggest that it does not need to be disposed. That also seems wrong.

Everybody judges by himself. I don't like to add to mine code something just for the sake of addition. It means if I add IDisposable, it means I've created some kind of functionality that GC can't manage or I suppose it will not be able to manage it's lifetime properly.

I see a lot of answers have shifted to talk about using IDisposable for both managed and unmanaged resources. I'd suggest this article as one of the best explanations that I've found for how IDisposable should actually be used.

https://www.codeproject.com/Articles/29534/IDisposable-What-Your-Mother-Never-Told-You-About

For the actual question; should you use IDisposable to clean up managed objects that are taking up a lot of memory the short answer would be no. The reason is that once your object that is holding the memory goes out of scope it is ready for collection. At that point any referenced child objects are also out of scope and will get collected.

The only real exception to this would be if you have a lot of memory tied up in managed objects and you've blocked that thread waiting for some operation to complete. If those objects where not going to be needed after that call completed then setting those references to null might allow the garbage collector to collect them sooner. But that scenario would represent bad code that needed to be refactored - not a use case of IDisposable.

I did't understood why somehone put -1 at your answer

One issue with this that I see is people keep thinking that having a file open with a using statement uses Idisposable. when the using statement finishes they do not close because well the GC will garbage collect call dispose, yada yada and the file will get closed. Trust me it does, but not fast enough. Sometimes that same file needs to be reopened immediately. This is what is currently happening in VS 2019 .Net Core 5.0

you seem to be describing people using a disposable without a using statement but on a class that has a finalizer. the GC does not call dispose it calls the finalizer. As an example, FIleStream, if wrapped in a using statement, will close the file when disposed.

I assure you I know what I am talking about. Open a file WITH a using statement, modify it close and immediately try to reopen the same file and modify it again. Now do this 30 times in a row. I used to deal with 750,000 jpgs an hour to build build pdfs, and converting the original color jpgs into black and white. jpgs. These Jpgs were pages that were scanned from bills, some had 10 pages. GC is to slow, especially when you have a machine with 256 GB of ram. it collects when the Machine needs more ram

it only looks for objects that are not being used when it does look. you need to call file.Close() before the end of the using statement. Oh yeah try it with a database connection too, with real numbers, 800,000 connections, you know like a large bank might use, this is why people use connection pooling.

The most justifiable use case for disposal of managed resources, is preparation for the GC to reclaim resources that would otherwise never be collected.

A prime example is circular references.

Whilst it's best practice to use patterns that avoid circular references, if you do end up with (for example) a 'child' object that has a reference back to its 'parent', this can stop GC collection of the parent if you just abandon the reference and rely on GC - plus if you have implemented a finalizer, it'll never be called.

The only way round this is to manually break the circular references by setting the Parent references to null on the children.

Implementing IDisposable on parent and children is the best way to do this. When Dispose is called on the Parent, call Dispose on all Children, and in the child Dispose method, set the Parent references to null.

For the most part, the GC doesn't work by identifying dead objects, but rather by identifying live ones. After each gc cycle, for each object that has registered for finallization, is stored on the large object heap, or is the target of a live WeakReference, the system will check a flag which indicates that a live rooted reference was found in the last GC cycle, and will either add the object to a queue of objects needing immediate finalization, release the object from the large object heap, or invalidate the weak reference. Circular refs will not keep objects alive if no other refs exist.

Earn 10 reputation (not counting the association bonus) in order to answer this question. The reputation requirement helps protect this question from spam and non-answer activity.

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged c# .net garbage-collection idisposable or ask your own question.

////////Learning How Garbage Collectors Work - Part 1///////////////////////////////////////////////////////

This series is an attempt to learn more about how a real-life “Garbage Collector” (GC) works internally, i.e. not so much “what it does”, but “how it does it” at a low-level. I will be mostly be concentrating on the .NET GC, because I’m a .NET developer and also because it’s recently been Open Sourced so we can actually look at the code.

Note: If you do want to learn about what a GC does, I really recommend the talk Everything you need to know about .NET memory by Ben Emmett, it’s a fantastic talk that uses lego to explain what the .NET GC does (the slides are also available)

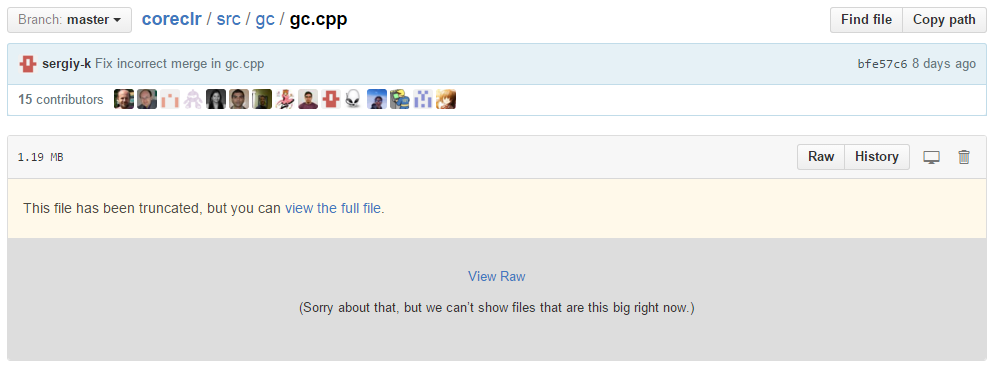

Well, trying to understand what the .NET GC does by looking at the source was my original plan, but if you go and take a look at the code on GitHub you will be presented with the message “This file has been truncated,…”:

This is because the file is 36,915 lines long and 1.19MB in size! Now before you send a PR to Microsoft that chops it up into smaller bits, you might want to read this discussion on reorganizing gc.cpp. It turns out you are not the only one who’s had that idea and your PR will probably be rejected, for some specific reasons.

Goals of the GC

So, as I’m not going to be able to read and understand a 36 KLOC .cpp source file any time soon, instead I tried a different approach and started off by looking through the excellent Book-of-the-Runtime (BOTR) section on the “Design of the Collector”. This very helpfully lists the following goals of the .NET GC (emphasis mine):

The GC strives to manage memory extremely efficiently and require very little effort from people who write managed code. Efficient means:

- GCs should occur often enough to avoid the managed heap containing a significant amount (by ratio or absolute count) of unused but allocated objects (garbage), and therefore use memory unnecessarily.

- GCs should happen as infrequently as possible to avoid using otherwise useful CPU time, even though frequent GCs would result in lower memory usage.

- A GC should be productive. If GC reclaims a small amount of memory, then the GC (including the associated CPU cycles) was wasted.

- Each GC should be fast. Many workloads have low latency requirements.

- Managed code developers shouldn’t need to know much about the GC to achieve good memory utilization (relative to their workload). – The GC should tune itself to satisfy different memory usage patterns.

So there’s some interesting points in there, in particular they twice included the goal of ensuring developers don’t have to know much about the GC to make it efficient. This is probably one of the main differences between the .NET and Java GC implementations, as explained in an answer to the Stack Overflow question “.Net vs Java Garbage Collector”

A difference between Oracle’s and Microsoft’s GC implementation ‘ethos’ is one of configurability.

Oracle provides a vast number of options (at the command line) to tweak aspects of the GC or switch it between different modes. Many options are of the -X or -XX to indicate their lack of support across different versions or vendors. The CLR by contrast provides next to no configurability; your only real option is the use of the server or client collectors which optimise for throughput verses latency respectively.

.NET GC Sample

So now we have an idea about what the goals of the GC are, lets take a look at how it goes about things. Fortunately those nice developers at Microsoft released a GC Sample that shows you, at a basic level, how you can use the full .NET GC in your own code. After building the sample (and finding a few bugs in the process), I was able to get a simple, single-threaded Workstation GC up and running.

What’s interesting about the sample application is that it clearly shows you what actions the .NET Runtime has to perform to make the GC work. So for instance, at a high-level the runtime needs to go through the following process to allocate an object:

AllocateObject(..)- See below for the code and explanation of the allocation process

CreateGlobalHandle(..)- If we want to store the object in a “strong handle/reference”, as opposed to a “weak” one. In C# code this would typically be a static variable. This is what tells the GC that the object is referenced, so that is can know that it shouldn’t be cleaned up when a GC collection happens.

ErectWriteBarrier(..)- For more information see “Marking the Card Table” below

Allocating an Object

AllocateObject(..) code from GCSample.cpp

Object * AllocateObject(MethodTable * pMT)

{

alloc_context * acontext = GetThread()->GetAllocContext();

Object * pObject;

size_t size = pMT->GetBaseSize();

uint8_t* result = acontext->alloc_ptr;

uint8_t* advance = result + size;

if (advance <= acontext->alloc_limit)

{

acontext->alloc_ptr = advance;

pObject = (Object *)result;

}

else

{

pObject = GCHeap::GetGCHeap()->Alloc(acontext, size, 0);

if (pObject == NULL)

return NULL;

}

pObject->RawSetMethodTable(pMT);

return pObject;

}

To understand what’s going on here, the BOTR again comes in handy as it gives us a clear overview of the process, from “Design of Allocator”:

When the GC gives out memory to the allocator, it does so in terms of allocation contexts. The size of an allocation context is defined by the allocation quantum.

- Allocation contexts are smaller regions of a given heap segment that are each dedicated for use by a given thread. On a single-processor (meaning 1 logical processor) machine, a single context is used, which is the generation 0 allocation context.

- The Allocation quantum is the size of memory that the allocator allocates each time it needs more memory, in order to perform object allocations within an allocation context. The allocation is typically 8k and the average size of managed objects are around 35 bytes, enabling a single allocation quantum to be used for many object allocations.

This shows how is is possible for the .NET GC to make allocating an object (or memory) such a cheap operation. Because of all the work that it has done in the background, the majority of the time an object allocation happens, it is just a case of incrementing a pointer by the number of bytes needed to hold the new object. This is what the code in the first half of the AllocateObject(..) function (above) is doing, it’s bumping up the free-space pointer (acontext->alloc_ptr) and giving out a pointer to the newly created space in memory.

It’s only when the current allocation context doesn’t have enough space that things get more complicated and potentially more expensive. At this point GCHeap::GetGCHeap()->Alloc(..) is called which may in turn trigger a GC collection before a new allocation context can be provided.

Finally, it’s worth looking at the goals that the allocator was designed to achieve, again from the BOTR:

- Triggering a GC when appropriate: The allocator triggers a GC when the allocation budget (a threshold set by the collector) is exceeded or when the allocator can no longer allocate on a given segment. The allocation budget and managed segments are discussed in more detail later.

- Preserving object locality: Objects allocated together on the same heap segment will be stored at virtual addresses close to each other.

- Efficient cache usage: The allocator allocates memory in allocation quantum units, not on an object-by-object basis. It zeroes out that much memory to warm up the CPU cache because there will be objects immediately allocated in that memory. The allocation quantum is usually 8k.

- Efficient locking: The thread affinity of allocation contexts and quantums guarantee that there is only ever a single thread writing to a given allocation quantum. As a result, there is no need to lock for object allocations, as long as the current allocation context is not exhausted.

- Memory integrity: The GC always zeroes out the memory for newly allocated objects to prevent object references pointing at random memory.

- Keeping the heap crawlable: The allocator makes sure to make a free object out of left over memory in each allocation quantum. For example, if there is 30 bytes left in an allocation quantum and the next object is 40 bytes, the allocator will make the 30 bytes a free object and get a new allocation quantum.

One of the interesting items this highlights is an advantage of GC systems, namely that you get efficient CPU cache usage or good object locality because memory is allocated in units. This means that objects created one after the other (on the same thread), will sit next to each other in memory.

Marking the “Card Table”

The 3rd part of the process of allocating an object was a call to ErectWriteBarrier(..) , which looks like this:

inline void ErectWriteBarrier(Object ** dst, Object * ref)

{

// if the dst is outside of the heap (unboxed value classes) then we simply exit

if (((uint8_t*)dst < g_lowest_address) || ((uint8_t*)dst >= g_highest_address))

return;

if ((uint8_t*)ref >= g_ephemeral_low && (uint8_t*)ref < g_ephemeral_high)

{

// volatile is used here to prevent fetch of g_card_table from being reordered

// with g_lowest/highest_address check above.

uint8_t* pCardByte = (uint8_t *)*(volatile uint8_t **)(&g_card_table) +

card_byte((uint8_t *)dst);

if(*pCardByte != 0xFF)

*pCardByte = 0xFF;

}

}

Now explaining what is going on here is probably an entire post on it’s own and fortunately other people have already done the work for me, if you are interested in finding our more take a look at the links at the end of this post.

But in summary, the card-table is an optimisation that allows the GC to collect a single Generation (e.g. Gen 0), but still know about objects that are referenced from other, older generations. For instance if you had an array, myArray = new MyClass[100] that was in Gen 1 and you wrote the following code myArray[5] = new MyClass(), a write barrier would be set-up to indicate that the MyClass object was referenced by a given section of Gen 1 memory.

Then, when the GC wants to perform the mark phase for a Gen 0, in order to find all the live-objects it uses the card-table to tell it in which memory section(s) of other Generations it needs to look. This way it can find references from those older objects to the ones stored in Gen 0. This is a space/time tradeoff, the card-table represents 4KB sections of memory, so it still has to scan through that 4KB chunk, but it’s better than having to scan the entire contents of the Gen 1 memory when it wants to carry of a Gen 0 collection.

If it didn’t do this extra check (via the card-table), then any Gen 0 objects that were only referenced by older objects (i.e. those in Gen 1/2) would not be considered “live” and would then be collected. See the image below for what this looks like in practice:

Image taken from Back To Basics: Generational Garbage Collection

GC and Execution Engine Interaction

The final part of the GC sample that I will be looking at is the way in which the GC needs to interact with the .NET Runtime Execution Engine (EE). The EE is responsible for actually running or coordinating all the low-level things that the .NET runtime needs to-do, such as creating threads, reserving memory and so it acts as an interface to the OS, via Windows and Unix implementations.

To understand this interaction between the GC and the EE, it’s helpful to look at all the functions the GC expects the EE to make available:

void SuspendEE(GCToEEInterface::SUSPEND_REASON reason)void RestartEE(bool bFinishedGC)void GcScanRoots(promote_func* fn, int condemned, int max_gen, ScanContext* sc)void GcStartWork(int condemned, int max_gen)void AfterGcScanRoots(int condemned, int max_gen, ScanContext* sc)void GcBeforeBGCSweepWork()void GcDone(int condemned)bool RefCountedHandleCallbacks(Object * pObject)bool IsPreemptiveGCDisabled(Thread * pThread)void EnablePreemptiveGC(Thread * pThread)void DisablePreemptiveGC(Thread * pThread)void SetGCSpecial(Thread * pThread)alloc_context * GetAllocContext(Thread * pThread)bool CatchAtSafePoint(Thread * pThread)void AttachCurrentThread()void GcEnumAllocContexts (enum_alloc_context_func* fn, void* param)void SyncBlockCacheWeakPtrScan(HANDLESCANPROC, uintptr_t, uintptr_t)void SyncBlockCacheDemote(int /*max_gen*/)void SyncBlockCachePromotionsGranted(int /*max_gen*/)

If you want to see how the .NET Runtime performs these “tasks”, you can take a look at the real implementation. However in the GC Sample these methods are mostly stubbed out as no-ops. So that I could get an idea of the flow of the GC during a collection, I added simple print(..) statements to each one, then when I ran the GC Sample I got the following output:

SuspendEE(SUSPEND_REASON = 1)

GcEnumAllocContexts(..)

GcStartWork(condemned = 0, max_gen = 2)

GcScanRoots(condemned = 0, max_gen = 2)

AfterGcScanRoots(condemned = 0, max_gen = 2)

GcScanRoots(condemned = 0, max_gen = 2)

GcDone(condemned = 0)

RestartEE(bFinishedGC = TRUE)

Which fortunately corresponds nicely with the GC phases for WKS GC with concurrent GC off as outlined in the BOTR:

- User thread runs out of allocation budget and triggers a GC.

- GC calls SuspendEE to suspend managed threads.

- GC decides which generation to condemn.

- Mark phase runs.

- Plan phase runs and decides if a compacting GC should be done.

- If so relocate and compact phase runs. Otherwise, sweep phase runs.

- GC calls RestartEE to resume managed threads.

- User thread resumes running.

Further Information

If you want to find out any more information about Garbage Collectors, here is a list of useful links:

- General

- Marking the Card Table

GC Sample Code Layout (for reference)

GC Sample Code (under \sample)

- GCSample.cpp

- gcenv.h

- gcenv.ee.cpp

- gcenv.windows.cpp

- gcenv.unix.cpp

GC Sample Environment (under \env)

- common.cpp

- common.h

- etmdummy.g

- gcenv.base.h

- gcenv.ee.h

- gcenv.interlocked.h

- gcenv.interlocked.inl

- gcenv.object.h

- gcenv.os.h

- gcenv.structs.h

- gcenv.sync.h

GC Code (top-level folder)

- gc.cpp (36,911 lines long!!)

- gc.h

- gccommon.cpp

- gcdesc.h

- gcee.cpp

- gceewks.cpp

- gcimpl.h

- gcrecord.h

- gcscan.cpp

- gcscan.h

- gcsvr.cpp

- gcwks.cpp

- handletable.h

- handletable.inl

- handletablecache.cpp

- gandletablecore.cpp

- handletablepriv.h

- handletablescan.cpp

- objecthandle.cpp

- objecthandle.h

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

Visualising the .NET Garbage Collector

As part of an ongoing attempt to learn more about how a real-life Garbage Collector (GC) works (see part 1) and after being inspired by Julia Evans’ excellent post gzip + poetry = awesome I spent a some time writing a tool to enable a live visualisation of the .NET GC in action.

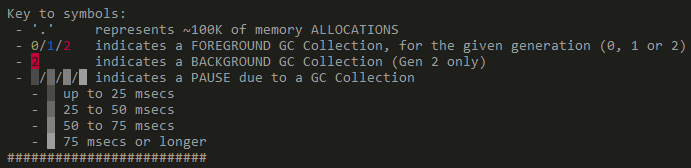

The output from the tool is shown below, click to Play/Stop (direct link to gif). The full source is available if you want to take a look.

Capturing GC Events in .NET

Fortunately there is a straight-forward way to capture the raw GC related events, using the excellent TraceEvent library that provides a wrapper over the underlying ETW Events the .NET GC outputs.

It’s a simple as writing code like this :

session.Source.Clr.GCAllocationTick += allocationData =>

{

if (ProcessIdsUsedInRuns.Contains(allocationData.ProcessID) == false)

return;

totalBytesAllocated += allocationData.AllocationAmount;

Console.Write(".");

};

Here we are wiring up a callback each time a GCAllocationTick event is fired, other events that are available include GCStart, GCEnd, GCSuspendEEStart, GCRestartEEStart and many more.

As well outputting a visualisation of the raw events, they are also aggregated so that a summary can be produced:

Memory Allocations:

1,065,720 bytes currently allocated

1,180,308,804 bytes have been allocated in total

GC Collections:

16 in total (12 excluding B/G)

2 - generation 0

9 - generation 1

1 - generation 2

4 - generation 2 (B/G)

Time in GC: 1,300.1 ms (108.34 ms avg)

Time under test: 3,853 ms (33.74 % spent in GC)

Total GC Pause time: 665.9 ms

Largest GC Pause: 75.99 ms

GC Pauses

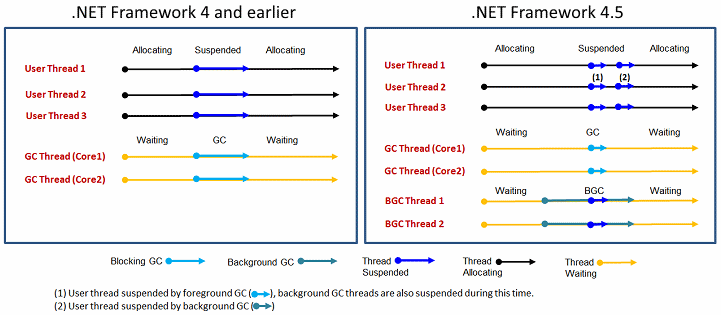

Most of the visualisation and summary information is relatively easy to calculate, however the timings for the GC pauses are not always straight-forward. Since .NET 4.5 the Server GC has 2 main modes available the new Background GC mode and the existing Foreground/Non-Concurrent one. The .NET Workstation GC has had a Background GC mode since .NET 4.0 and a Concurrent mode before that.

The main benefit of the Background mode is that it reduces GC pauses, or more specifically it reduces the time that the GC has to suspend all the user threads running inside the CLR. The problem with these “stop-the-world” pauses, as they are also known, is that during this time your application can’t continue with whatever it was doing and if the pauses last long enough users will notice.

As you can see in the image below (courtesy of the .NET Blog) , with the newer Background mode in .NET 4.5 the time during which user-threads are suspended is much smaller (the dark blue arrows). They only need to be suspended for part of the GC process, not the entire duration.

Foreground (Blocking) GC flow

So calculating the pauses for a Foreground GC (this means all Gen 0/1 GCs and full blocking GCs) is relatively straightforward, using the info from the excellent blog post by Maoni Stephens the main developer on the .NET GC:

GCSuspendEE_V1GCSuspendEEEnd_V1<– suspension is doneGCStart_V1GCEnd_V1<– actual GC is doneGCRestartEEBegin_V1GCRestartEEEnd_V1<– resumption is done.

So the pause is just the difference between the timestamp of the GCSuspendEEEnd_V1 event and that of the GCRestartEEEnd_V1.

Background GC flow

However for Background GC (Gen 2) it is more complicated, again from Maoni’s blog post:

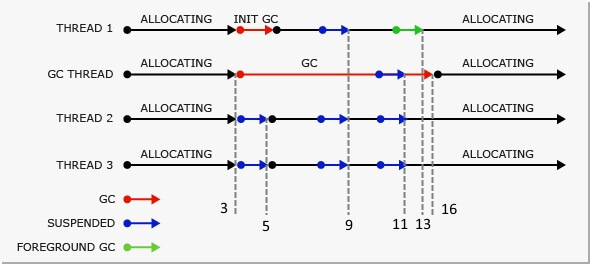

GCSuspendEE_V1GCSuspendEEEnd_V1GCStart_V1<– Background GC startsGCRestartEEBegin_V1GCRestartEEEnd_V1<– done with the initial suspensionGCSuspendEE_V1GCSuspendEEEnd_V1GCRestartEEBegin_V1GCRestartEEEnd_V1<– done with Background GC’s own suspensionGCSuspendEE_V1GCSuspendEEEnd_V1<– suspension for Foreground GC is doneGCStart_V1GCEnd_V1<– Foreground GC is doneGCRestartEEBegin_V1GCRestartEEEnd_V1<– resumption for Foreground GC is doneGCEnd_V1<– Background GC ends

It’s a bit easier to understand these steps by using an annotated version of the image from the MSDN page on GC (the numbers along the bottom correspond to the steps above)

But there’s a few caveats that make it trickier to calculate the actual time:

Of course there could be more than one foreground GC, there could be 0+ between line 5) and 6), and more than one between line 9) and 16).

We may also decide to do an ephemeral GC before we start the BGC (as BGC is meant for gen2) so you might also see an ephemeral GC between line 3) and 4) – the only difference between it and a normal ephemeral GC is you wouldn’t see its own suspension and resumption events as we already suspended/resumed for BGC purpose.

Age of Ascent - GC Pauses

Finally, if you want a more dramatic way of visualising a “Stop the World” or more accurately a “Stop the Universe” GC pause, take a look at the video below. The GC pause starts at around 7 seconds in (credit to Ben Adams and Age of Ascent)

////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

GC Pauses and Safe Points

GC pauses are a popular topic, if you do a google search, you’ll see lots of articles explaining how to measure and more importantly how to reduce them. This issue is that in most runtimes that have a GC, allocating objects is a quick operation, but at some point in time the GC will need to clean up all the garbage and to do this is has to pause the entire runtime (except if you happen to be using Azul’s pauseless GC for Java).

The GC needs to pause the entire runtime so that it can move around objects as part of it’s compaction phase. If these objects were being referenced by code that was simultaneously executing then all sorts of bad things would happen. So the GC can only make these changes when it knows that no other code is running, hence the need to pause the entire runtime.

GC Flow

In a previous post I demonstrated how you can use ETW Events to visualise what the .NET Garbage Collector (GC) is doing. That post included the following GC flow for a Foreground/Blocking Collection (info taken from the excellent blog post by Maoni Stephens the main developer on the .NET GC):

GCSuspendEE_V1GCSuspendEEEnd_V1<– suspension is doneGCStart_V1GCEnd_V1<– actual GC is doneGCRestartEEBegin_V1GCRestartEEEnd_V1<– resumption is done.

This post is going to be looking at how the .NET Runtime brings all the threads in an application to a safe-point so that the GC can do it’s work. This corresponds to what happens between step 1) GCSuspendEE_V1 and 2) GCSuspendEEEnd_V1 in the flow above.

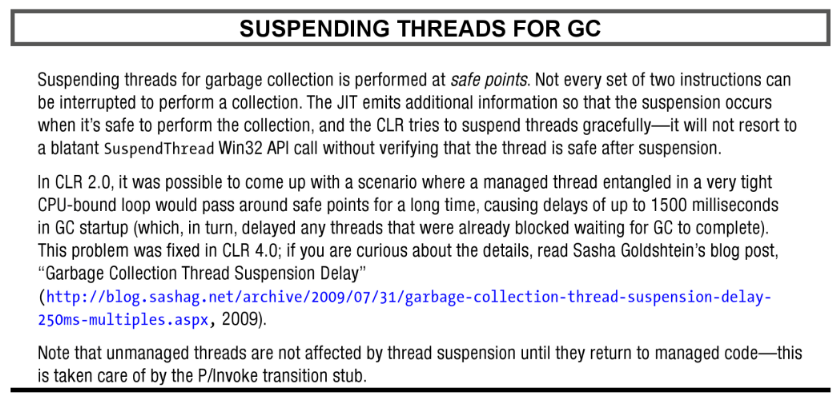

For some background this passage from the excellent Pro .NET Performance: Optimize Your C# Applications explains what’s going on:

Technically the GC itself doesn’t actually perform a suspension, it calls into the Execution Engine (EE) and asks that to suspend all the running threads. This suspension needs to be as quick as possible, because the time taken contributes to the overall GC pause. Therefore this Time To Safe Point (TTSP) as it’s known, needs to be minimised, the CLR does this by using several techniques.

GC suspension in Runtime code

Inside code that it controls, the runtime inserts method calls to ensure that threads can regularly poll to determine when they need to suspend. For instance take a look at the following code snippet from the IndexOfCharArray() method (which is called internally by String.IndexOfAny(..)). Notice that it contains multiple calls to the macro FC_GC_POLL_RET():

FCIMPL4(INT32, COMString::IndexOfCharArray, StringObject* thisRef, CHARArray* valueRef, INT32 startIndex, INT32 count)

{

// <OTHER CODE REMOVED>

// use probabilistic map, see (code:InitializeProbabilisticMap)

int charMap[PROBABILISTICMAP_SIZE] = {0};

InitializeProbabilisticMap(charMap, valueChars, valueLength);

for (int i = startIndex; i < endIndex; i++) {

WCHAR thisChar = thisChars[i];

if (ProbablyContains(charMap, thisChar))

if (ArrayContains(thisChars[i], valueChars, valueLength) >= 0) {

FC_GC_POLL_RET();

return i;

}

}

FC_GC_POLL_RET();

return -1;

}

The are lots of other places in the runtime where these calls are inserted, to ensure that a GC suspension can happen as soon as possible. However having these calls spread throughout the code has an overhead, so the runtime uses a special trick to ensure the cost is only paid when a suspension has actually been requested, From jithelp.asm you can see that the method call is re-written to a nop routine when not needed and only calls the actual JIT_PollGC() function when absolutely required:

; Normally (when we're not trying to suspend for GC), the

; CORINFO_HELP_POLL_GC helper points to this nop routine. When we're

; ready to suspend for GC, we whack the Jit Helper table entry to point

; to the real helper. When we're done with GC we whack it back.

PUBLIC @JIT_PollGC_Nop@0

@JIT_PollGC_Nop@0 PROC

ret

@JIT_PollGC_Nop@0 ENDP

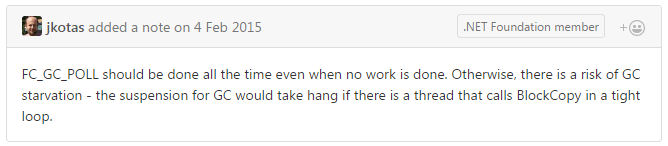

However calls to FC_GC_POLL need to be carefully inserted in the correct locations, too few and the EE won’t be able to suspend quickly enough and this will cause excessive GC pauses, as this comment from one of the .NET JIT devs confirms:

GC suspension in User code

Alternatively, in code that the runtime doesn’t control things are a bit different. Here the JIT analyses the code and classifies it as either:

- Partially interruptible

- Fully interruptible

Partially interruptible code can only be suspended at explicit GC poll locations (i.e. FC_GC_POLL calls) or when it calls into other methods. On the other hand fully interruptible code can be interrupted or suspended at any time, as every line within the method is considered a GC safe-point.