注:本文为 “数学符号” 相关合辑。

英文引文,机翻未校。

略作重排,未整理去重。

如有内容异常,请看原文。

The Wild and Contentious History of Mathematical Symbols

数学符号鲜为人知且充满争议的历史

2025-02-07 00:00:00

A mathematician has uncovered the stories behind the symbols used in math

一位数学家揭开了数学所用符号背后的故事

Shideh Ghandeharizadeh

希德・甘德哈里扎德

May 2025 Issue

2025 年 5 月期

War in Europe is a staple topic in the study of history, but there’s one major conflict most history books won’t teach you: the battle of the equal sign,

=

=

=. These two parallel lines were, in fact, the source of serious dispute among European mathematicians in the mid-1500s. This dispute is just one of many such little-known events; for example, another debate has been raging for centuries over who invented the symbol for zero,

0

0

0. In The Language of Mathematics: The Stories behind the Symbols (Princeton University Press, 2025), author and mathematician Raúl Rojas explores these and other examples of the complex, and sometimes uncertain, history of mathematical symbolism.

欧洲战争是历史研究中的常见主题,但有一场重大 “冲突” 是大多数历史书不会提及的:等号

=

=

= 之争。事实上,这两条平行线在 16 世纪中期曾引发欧洲数学家之间的激烈争议。这类鲜为人知的事件还有很多,比如 “谁发明了零符号

0

0

0” 的争论就已持续了数个世纪。在《数学语言:符号背后的故事》(普林斯顿大学出版社,2025 年)一书中,作者兼数学家劳尔・罗哈斯(Raúl Rojas)探讨了这些案例及其他实例,展现了数学符号体系复杂且有时模糊不清的历史。

Over the years competing camps have considered adopting one or another notation for many different aspects of mathematics. Rojas guides us along the historical arc of mathematics, intertwining its evolution with the cultural, philosophical and practical needs of the societies that shaped and relied on it.

多年来,在数学的多个领域,相互竞争的阵营都曾考虑采用不同的记法。罗哈斯带领我们梳理数学的历史脉络,将数学的演变与塑造并依赖它的社会所存在的文化、哲学及实际需求交织在一起。

Scientific American spoke to Rojas about this chronology, the deeply engaging humanity of mathematics, and the egos at play in defining the mathematical language we take for granted today.

《科学美国人》就这一时间线、数学极具吸引力的人文内涵,以及在定义我们如今习以为常的数学语言时背后起作用的个人野心,对罗哈斯进行了采访。

An edited transcript of the interview follows.

以下是经编辑后的采访实录。

What inspired you to write this book about the stories behind these symbols?

是什么启发你撰写这本关于这些符号背后故事的书?

I started teaching in 1977, and across my nearly 50 years I noticed that students were always interested in the history of mathematics. When you teach linear algebra or calculus, it’s important to tell students about the people who developed the concepts and how those concepts came to be. I started doing seminars on the history of mathematical notation, and I had every student study one symbol and explain its origin. I found that those students who are falling asleep in class suddenly wake up when you add a human story behind the abstract symbols.

我从 1977 年开始教书,在近 50 年的教学生涯中,我发现学生们一直对数学史很感兴趣。当你教授线性代数或微积分时,向学生介绍那些提出相关概念的人以及这些概念的形成过程十分重要。后来我开设了关于数学记法史的研讨会,让每个学生都研究一个符号并解释其起源。我发现,当你为抽象符号赋予人类故事背景时,那些在课堂上昏昏欲睡的学生都会突然清醒过来。

Throughout the book, you discuss symbols that ultimately failed to become the standard en route to the notation we know today. How were these things decided?

在书中,你探讨了那些在形成我们如今所知的记法的过程中,最终未能成为标准的符号。这些标准是如何确定的?

One of the interesting things about the history of mathematical notation is its regional variation over the centuries. There was one kind of notation in Italy, another in Germany, the U.K. and France. All these different regions were producing symbols, and with the advent of the printing press, there was an explosion of proposals. So how did it happen that a single symbol could become standardized?

数学记法史的有趣之处之一在于,几个世纪以来它存在地区差异。意大利有一套记法,德国、英国和法国则各有另一套记法。所有这些不同地区都在创造符号,而随着印刷术的出现,大量记法提案开始涌现。那么,单个符号是如何实现标准化的呢?

One good example is the symbol of equality,

=

=

=. This relation was mostly expressed with words in the beginning. Later René Descartes in France started using a rotated Taurus symbol,

α

\alpha

α, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in Germany used a wedgelike shape. And before Descartes and Leibniz, Robert Recorde in the U.K. invented the equal sign we use today, though in an elongated form. Mathematicians found themselves in a kind of battle over arithmetical symbols based on popularity. A notable contest was between

+

+

+ and

−

-

− versus

p

p

p and

m

m

m, which the Italians preferred for denoting operations. Eventually the plus and minus signs became universal, as did the English symbol for equality, but only after decades of famous mathematicians competing in these popularity contests to set the trends.

等号

=

=

= 就是一个很好的例子。起初,“相等” 这一关系主要用文字表述。后来,法国的勒内・笛卡尔(René Descartes)开始使用旋转的金牛座符号

α

\alpha

α,德国的戈特弗里德・威廉・莱布尼茨(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz)则使用楔形符号。而在笛卡尔和莱布尼茨之前,英国的罗伯特・雷科德(Robert Recorde)就发明了我们如今使用的等号,只不过当时是加长形式。数学家们围绕算术符号展开了一场基于 “受欢迎程度” 的较量。其中一个著名的竞争是 “

+

+

+” 和 “

−

-

−” 与 “

p

p

p” 和 “

m

m

m” 的对抗 —— 意大利人更倾向于用 “

p

p

p” 和 “

m

m

m” 表示运算。最终,加号和减号成了通用符号,英国式等号也同样得以普及,但这是在数十年间众多著名数学家通过 “人气竞赛” 争夺趋势主导权之后才实现的。

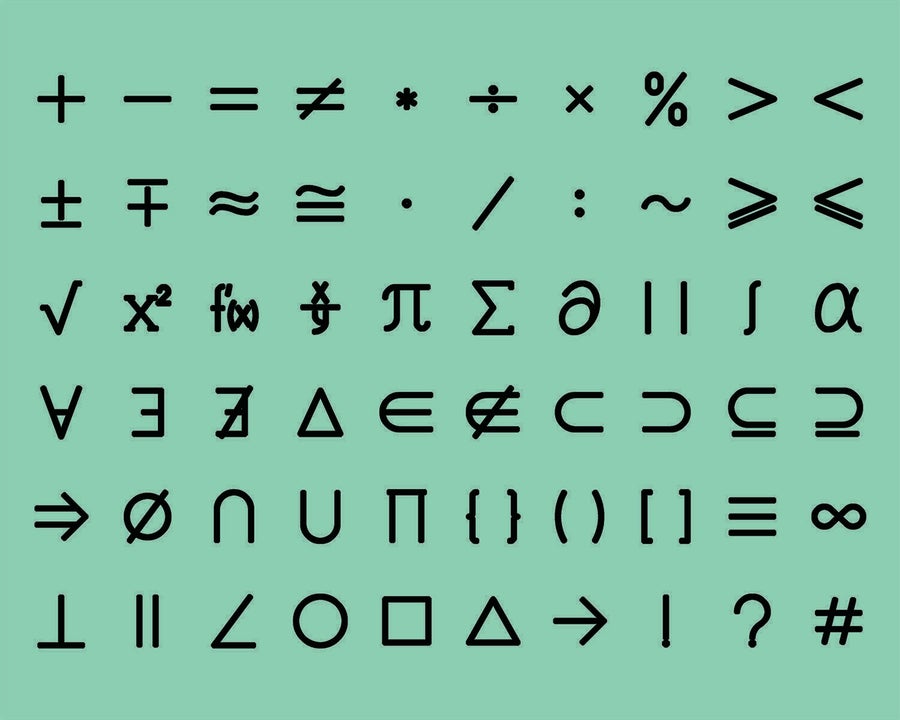

Nadiinko/Getty Images

Is there a particular symbol in the history of mathematics that significantly influenced how we think about abstract concepts?

数学史上是否有某个符号对我们思考抽象概念的方式产生了重大影响?

There is one symbol, which has an incredibly long history that has not yet been fully written:

0

0

0. How did it arise? We know it was used by the Babylonians, but they didn’t write a

0

0

0 as we know it. They worked with a positional base-60 system and simply left a blank where we would write

0

0

0 today. This was their natural way of showing zero: if it’s nothing, then you don’t have to write anything.

有一个符号拥有极其悠久且尚未被完整记载的历史,那就是

0

0

0。它是如何产生的?我们知道巴比伦人曾使用过 “零” 的概念,但他们并没有写出我们如今所知的

0

0

0。他们采用六十进制位值制,在如今我们会写

0

0

0 的位置上直接留空。这是他们表示 “零” 的自然方式:既然是 “无”,就无需书写任何东西。

Later, through the conquests of Alexander the Great, the Greeks took the positional number system to India, where we believe the Hindu culture developed the first representation of

0

0

0. There’s a friendly competition among anthropologists working to find the oldest instances of

0

0

0 in writing. Every five or six years someone finds an older engraving. It’s fascinating because this simple symbol we use every single day without thinking about it has a history that encompasses thousands of years.

后来,通过亚历山大大帝的征服行动,希腊人将位值制数字系统带到了印度。我们认为,印度文化正是在那里创造出了

0

0

0 的首个符号表示。人类学家之间正展开一场良性竞争,试图找到最早的书面

0

0

0 实例。每过五六年,就会有人发现更早的相关铭文。这一现象十分有趣,因为这个我们每天都在使用、且习以为常的简单符号,其历史竟跨越了数千年。

You describe Gerhard Gentzen’s “for all” symbol (

∀

\forall

∀) as a “cubist tear flowing from an eye that Picasso could have painted.” What’s the story behind that notation?

你将格哈德・根岑(Gerhard Gentzen)的 “全称量词” 符号(

∀

\forall

∀)描述为 “一滴毕加索或许会画的立体主义风格泪珠”。这个符号背后有什么故事?

Gentzen’s life is deeply tragic to me. He was an exceptional mathematician who, like many others in Nazi Germany, compromised with the regime. Although he was never a political person, he became a member of the Nazi Party and later joined the SS—the most criminal arm of the regime. Absorbed in his work, he did these things to advance his career. Even after the war, he expressed no guilt, claiming he was neither a soldier nor doing anything wrong. He had taken a position at the University of Prague, however, displacing others under Nazi occupation. Ultimately he chose not to flee after the war, was captured and died of starvation in prison.

在我看来,根岑的一生极具悲剧色彩。他是一位杰出的数学家,但和纳粹德国的许多人一样,他与该政权妥协了。尽管他并非热衷政治之人,却加入了纳粹党,后来还成为了党卫军(该政权最具犯罪性质的分支)成员。他沉迷于工作,做出这些事是为了推进自己的事业。即便在战后,他也毫无愧疚之意,声称自己既不是士兵,也没有做错任何事。然而,在纳粹占领期间,他曾在布拉格大学任职,取代了他人的职位。最终,他在战后选择不逃亡,随后被捕并在狱中饿死。

There is no excusing his actions, but his life remains tragic from beginning to end, especially when considering what he might have accomplished had he taken a different path. It’s fascinating that such a simple symbol—this upside-down A (

∀

\forall

∀)—carries such a complex and poignant history.

他的行为无可辩解,但他的一生从头到尾都充满悲剧色彩,尤其是当你想到如果他选择不同的人生道路,或许能取得怎样的成就时。令人感慨的是,这样一个简单的符号 —— 这个倒写的 A(

∀

\forall

∀)—— 竟承载着如此复杂且令人唏嘘的历史。

What do you hope readers—especially those outside the math community—might take away from your book?

你希望读者 —— 尤其是数学界之外的读者 —— 能从你的书中获得什么?

It’s important to understand that mathematics is a historical process, just like any social science or politics. Mathematics didn’t arise complete and finished through the work of just one mathematician; it has a cultural history that spans many years. For centuries we’ve been looking at the sky or computing. In school, they teach addition and multiplication but rarely explain the origins or history of the symbols. This vast history is untold, but the excitement of doing mathematics comes from this knowledge that you are building on a framework developed by fascinating people over thousands of years.

理解数学是一个历史发展过程十分重要,就像社会科学或政治领域一样。数学并非通过某一位数学家的努力就以完整形态出现;它拥有跨越多年的文化历史。数百年来,我们一直在观测星空或进行计算。在学校里,老师会教授加法和乘法,却很少解释这些符号的起源或历史。这段宏大的历史鲜为人知,但从事数学研究的乐趣,恰恰源于你知晓自己正在一个由数千年来形形色色的人所建立的框架之上继续发展。

MATHEMATICAL NOTATION AND SYMBOLS: HISTORY AND STANDARDIZATION

数学符号与记法:历史与标准化

Rosemary Varghese, Assistant Professor of Mathematics, Govt. First Grade College, Mulbagal.

罗斯玛丽·瓦尔盖塞(Rosemary Varghese),马尔巴加尔政府一级学院(Govt. First Grade College, Mulbagal)数学助理教授。

Abstract:

摘要:

Mathematical notation and symbols constitute a universal language essential for the articulation and exchange of mathematical ideas. This study explores the historical development and standardization of mathematical notation, tracing its evolution from ancient civilizations to modern times. The origins of mathematical notation can be found in early societies such as the Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks, who utilized rudimentary symbols and numeral systems for practical applications like trade and astronomy. The introduction of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, featuring positional notation and the concept of zero, marked a significant advancement, revolutionizing mathematical calculations and theories.

数学符号与记法是阐述和交流数学思想的核心通用语言。本研究探讨数学记法的历史发展与标准化进程,追溯其从古代文明到现代社会的演变轨迹。数学记法的起源可追溯至古埃及、古巴比伦和古希腊等早期文明,这些文明为贸易、天文学等实际应用,创造了基础符号与数字系统。具有位值记法和零概念的印度-阿拉伯数字系统的出现,是数学发展的重要里程碑,彻底革新了数学计算与理论体系。

The Renaissance period catalyzed further refinement of mathematical notation. Key figures such as François Viète, Robert Recorde, and René Descartes made substantial contributions, introducing systematic symbols for algebraic expressions and geometric concepts. Their innovations laid the groundwork for modern algebraic notation and coordinate systems. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the formalization of several essential symbols, including the plus (+) and minus (−) signs, multiplication (×), and division (÷) symbols, as well as π and i for representing mathematical constants. These symbols facilitated more complex mathematical operations and theories, such as calculus, developed by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

文艺复兴时期推动了数学记法的进一步完善。弗朗索瓦·韦达(François Viète)、罗伯特·雷科德(Robert Recorde)和勒内·笛卡尔(René Descartes)等关键人物贡献卓著,为代数表达式和几何概念引入了系统性符号。他们的创新为现代代数记法和坐标系奠定了基础。17 世纪和 18 世纪见证了多个核心符号的规范化,包括加号(

+

+

+)、减号(

−

-

−)、乘号(

×

\times

×)、除号(

÷

\div

÷),以及代表数学常数的

π

\pi

π 和

i

i

i。这些符号为更复杂的数学运算与理论(如艾萨克·牛顿(Isaac Newton)和戈特弗里德·威廉·莱布尼茨(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz)创立的微积分)提供了便利。

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the development of set theory, symbolic logic, and digital typesetting further standardized mathematical notation, enhancing global communication and consistency. The advent of digital tools and computational systems has introduced new symbols and conventions to address contemporary needs. Overall, the history and standardization of mathematical notation reflect its dynamic nature and crucial role in advancing mathematical knowledge across diverse disciplines and cultures.

19 世纪和 20 世纪,集合论、符号逻辑和数字排版技术的发展进一步推动了数学记法的标准化,提升了全球数学交流的效率与一致性。数字工具与计算系统的出现,催生了满足现代需求的新符号与新规则。总体而言,数学记法的历史与标准化进程,体现了其动态发展的特性,以及在跨学科、跨文化推进数学知识过程中的核心作用。

Keywords: Mathematics, Notation, Symbols, History and Standardization.

关键词:数学(Mathematics)、记法(Notation)、符号(Symbols)、历史与标准化(History and Standardization)。

INTRODUCTION:

引言:

Mathematical notation and symbols serve as the essential language of mathematics, enabling precise and efficient communication of complex ideas and operations. This system of representation has evolved significantly over millennia, originating from rudimentary methods in ancient civilizations to the sophisticated symbols used in modern mathematics. Early cultures like the Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks laid the groundwork with their own numerical and symbolic systems, which were primarily used for trade, astronomy, and basic arithmetic. The introduction of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, with its place value and zero, marked a revolutionary shift in mathematical notation, facilitating more advanced calculations and concepts.

数学符号与记法是数学学科的核心语言,能够精准、高效地传递复杂数学思想与运算。这套表示体系历经数千年演变,从古代文明的基础记法,发展为现代数学中的精密符号系统。古埃及、古巴比伦和古希腊等早期文明,用各自的数字与符号系统奠定了基础,这些系统最初主要应用于贸易、天文学和基础算术。具有位值概念与零的印度-阿拉伯数字系统的引入,是数学记法的革命性转折,为更高级的计算与概念提供了可能。

The Renaissance period further advanced mathematical notation, with key figures such as François Viète, Robert Recorde, and René Descartes contributing to the development of algebraic symbols and notation. The 17th and 18th centuries saw the standardization of various mathematical symbols, including the plus and minus signs, pi (π), and the imaginary unit (i), which were crucial for the expansion of calculus and algebra. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the formalization of set theory and symbolic logic, along with advancements in digital typesetting, standardized and globalized mathematical notation. Today, mathematical notation is integral to various fields, from pure mathematics to applied sciences and engineering. Its continuous evolution reflects the dynamic nature of mathematical inquiry and the need for precise and universal expression of mathematical concepts.

文艺复兴时期进一步推动了数学记法的发展,弗朗索瓦·韦达(François Viète)、罗伯特·雷科德(Robert Recorde)和勒内·笛卡尔(René Descartes)等关键人物,为代数符号与记法的发展做出了贡献。17 世纪和 18 世纪,多个数学符号实现规范化,包括加号、减号、圆周率(

π

\pi

π)和虚数单位(

i

i

i),这些符号对微积分与代数的拓展至关重要。19 世纪和 20 世纪,集合论与符号逻辑的形式化,以及数字排版技术的进步,使数学记法实现标准化并走向全球化。如今,数学记法已成为纯数学、应用科学、工程学等多个领域的核心组成部分。其持续演变体现了数学探索的动态特性,也反映了对数学概念进行精准、通用表达的需求。

OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY:

研究目标:

This study explores the historical development and standardization of mathematical notation, tracing its evolution from ancient civilizations to modern times.

本研究探讨数学记法的历史发展与标准化进程,追溯其从古代文明到现代社会的演变轨迹。

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY:

研究方法:

This study is based on secondary sources of data such as articles, books, journals, research papers, websites and other sources.

本研究基于二手数据源开展,包括期刊文章、书籍、学术期刊、研究论文、网站及其他资料。

MATHEMATICAL NOTATION AND SYMBOLS: HISTORY AND STANDARDIZATION

数学符号与记法:历史与标准化

Mathematical notation is a written system used to represent mathematical concepts, symbols, and formulas. It has evolved over thousands of years, with significant contributions from various cultures and mathematicians. The standardization of these notations plays a crucial role in enabling effective communication and understanding of mathematical ideas across different regions and time periods.

数学记法是用于表示数学概念、符号与公式的书面体系。它历经数千年演变,不同文化与数学家均为此做出了重要贡献。数学记法的标准化,对跨地区、跨时代高效交流与理解数学思想具有核心作用。

1. Early History of Mathematical Notation

1. 数学记法的早期历史

Ancient Civilizations: Mathematical notation has roots stretching back to ancient civilizations where the need for record-keeping and trade necessitated the development of number systems and basic symbols.

古代文明:数学记法的起源可追溯至古代文明。当时,记录保存与贸易活动的需求,推动了数字系统与基础符号的发展。

Egyptians: The ancient Egyptians used hieroglyphics to represent numbers. Their system was based on powers of ten, which allowed them to perform arithmetic operations essential for tasks like land measurement and resource distribution. Symbols were used to denote quantities such as 1, 10, 100, and so forth, and combinations of these symbols represented larger numbers. This system was somewhat cumbersome for complex calculations but was effective for their needs.

古埃及:古埃及人使用象形文字表示数字,其数字系统以 10 的幂为基础,能够完成土地测量、资源分配等任务所需的算术运算。他们用特定符号表示 1、10、100 等数量,通过符号组合表示更大的数。这套系统虽对复杂计算而言略显繁琐,但能满足当时的需求。

Babylonians: The Babylonians, around 2000 BCE, developed a base-60 numeral system, which was more advanced for its time. Their system included symbols for 1 and 10, which were combined to represent larger numbers. The sexagesimal (base-60) system is still used today for measuring time and angles. Although they did not have a symbol for zero, which limited their ability to perform certain calculations, their approach to place value and positional notation was a significant step forward.

古巴比伦:约公元前 2000 年,古巴比伦人发明了六十进制(base-60)数字系统,在当时处于领先水平。该系统用特定符号表示 1 和 10,通过符号组合表示更大的数。如今,六十进制(base-60)系统仍用于时间与角度测量。尽管古巴比伦人没有表示“零”的符号,限制了部分计算能力,但他们提出的位值思想与位值记法,是数学发展的重要进步。

Greeks: The Greeks made significant strides in the conceptualization of mathematics. Early Greek mathematicians like Pythagoras and Euclid used rhetorical notation, where mathematical ideas were expressed in words rather than symbols. However, they started using letters to denote specific quantities, such as in Diophantus’s work on algebra. Diophantus’s use of symbols for unknowns and his work on solving equations laid a foundation for future developments in algebraic notation.

古希腊:古希腊人在数学概念构建方面取得了重大突破。毕达哥拉斯(Pythagoras)和欧几里得(Euclid)等早期希腊数学家采用“文字记法”,即通过文字而非符号表达数学思想。但他们开始用字母表示特定数量,例如丢番图(Diophantus)在代数研究中的实践。丢番图用符号表示未知数,以及他在方程求解方面的研究,为后来代数记法的发展奠定了基础。

Roman Numerals

罗马数字

The Roman numeral system, developed by the Romans, was used for various purposes, including trade and construction. It featured symbols like I, V, X, L, C, D, and M to represent values. While it was effective for record-keeping and basic arithmetic, it lacked symbols for zero and was less efficient for more complex calculations compared to later systems. Roman numerals were not well-suited for operations such as multiplication and division, which became apparent as mathematical needs grew more sophisticated.

罗马数字系统由古罗马人发明,用于贸易、建筑等多种场景。该系统使用

I

I

I、

V

V

V、

X

X

X、

L

L

L、

C

C

C、

D

D

D、

M

M

M 等符号表示数值(分别对应 1、5、10、50、100、500、1000)。尽管罗马数字适用于记录保存与基础算术,但它没有表示“零”的符号,且相比后续数字系统,在复杂计算中效率更低。随着数学需求日益精密,罗马数字不适合乘法、除法等运算的缺陷逐渐显现。

Hindu-Arabic Numerals

印度-阿拉伯数字

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system, originating in India around the 6th century CE, marked a revolutionary shift in mathematics. This system introduced the concept of zero and positional notation, which allowed for a more efficient and versatile way of representing numbers.

印度-阿拉伯数字系统起源于公元 6 世纪的印度,是数学领域的革命性突破。该系统引入“零”的概念与位值记法,为数字表示提供了更高效、更多样的方式。

Indian Mathematicians: Early Indian mathematicians like Brahmagupta used a place-value system that included zero, which greatly simplified calculations. The system was further developed by scholars such as Aryabhata and Bhaskara, who made significant contributions to arithmetic, algebra, and trigonometry.

印度数学家:婆罗摩笈多(Brahmagupta)等早期印度数学家采用包含“零”的位值系统,大幅简化了计算过程。阿耶波多(Aryabhata)、巴斯卡拉(Bhaskara)等学者进一步完善了该系统,在算术、代数和三角学领域做出了重要贡献。

Transmission to the Islamic World: The numeral system spread to the Islamic world through translations of Indian mathematical texts. Mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi and Al-Kindi adopted and expanded upon these concepts, contributing to the development of algebra and arithmetic.

传入伊斯兰世界:通过印度数学文献的翻译,该数字系统传入伊斯兰世界。花拉子米(Al-Khwarizmi)、肯迪(Al-Kindi)等数学家采纳并拓展了这些概念,为代数与算术的发展做出了贡献。

Introduction to Europe: By the 12th century, the Hindu-Arabic numeral system reached Europe through translations of Arabic mathematical texts. The system’s advantages quickly became apparent, leading to its adoption across Europe and the gradual decline of Roman numerals for most mathematical purposes.

传入欧洲:12 世纪,通过阿拉伯数学文献的翻译,印度-阿拉伯数字系统传入欧洲。该系统的优势迅速显现,逐渐在欧洲普及,罗马数字在多数数学场景中的应用也随之逐渐减少。

2. Development of Algebraic Notation

2. 代数记法的发展

Diophantus and Symbolic Algebra: Diophantus of Alexandria, often referred to as the “father of algebra,” made significant contributions to algebraic notation. His work, Arithmetica, introduced an early form of symbolic notation for solving equations, though it was still largely rhetorical.

丢番图与符号代数:亚历山大的丢番图(Diophantus of Alexandria)常被称为“代数之父”,他对代数记法做出了重要贡献。其著作《算术》(Arithmetica)引入了用于方程求解的早期符号记法,尽管仍以文字表达为主。

Diophantine Equations: Diophantus focused on finding integer solutions to polynomial equations, now known as Diophantine equations. While his notation was not fully symbolic, his approach laid the groundwork for future developments in algebra.

丢番图方程:丢番图致力于寻找多项式方程的整数解,这类方程如今被称为“丢番图方程”。尽管他的记法尚未完全符号化,但其方法为代数的后续发展奠定了基础。

Legacy: Diophantus’s work influenced later mathematicians and contributed to the gradual shift from rhetorical to symbolic notation in algebra.

遗产:丢番图的研究影响了后世数学家,推动代数记法从“文字记法”逐步向“符号记法”转变。

Islamic Contributions

伊斯兰世界的贡献

During the Islamic Golden Age (8th to 14th centuries), mathematicians like Al-Khwarizmi played a pivotal role in the development of algebraic notation.

在伊斯兰黄金时代(8 至 14 世纪),花拉子米(Al-Khwarizmi)等数学家在代数记法发展中发挥了关键作用。

Al-Khwarizmi: His seminal work, Al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing), introduced systematic methods for solving linear and quadratic equations. Although his work was initially in a narrative form, it laid the foundation for later symbolic notation.

花拉子米:其经典著作《代数学》(Al-Kitab al-Mukhtasar fi Hisab al-Jabr wal-Muqabala,直译为“还原与对消计算概要”),提出了求解一次方程与二次方程的系统方法。尽管该著作最初以文字叙述形式呈现,但为后来符号记法的发展奠定了基础。

Al-Kindi and Others: Al-Kindi and other Islamic mathematicians expanded on these ideas, contributing to the development of algebra and the introduction of more advanced symbolic representations.

肯迪及其他学者:肯迪(Al-Kindi)等伊斯兰数学家拓展了这些思想,为代数发展及更高级符号表示法的引入做出了贡献。

Renaissance Advances

文艺复兴时期的进展

The Renaissance period in Europe saw the formalization and expansion of algebraic notation, driven by key mathematicians.

在欧洲文艺复兴时期,在关键数学家的推动下,代数记法实现了形式化与拓展。

François Viète: Viète is credited with introducing the systematic use of letters to represent both known and unknown quantities. His notation allowed for more general expressions and equations, laying the groundwork for modern algebra.

弗朗索瓦·韦达(François Viète):韦达被认为是系统性使用字母表示已知量与未知量的开创者。他的记法支持更通用的表达式与方程,为现代代数奠定了基础。

Robert Recorde: Recorde introduced the equal sign (=) in 1557, emphasizing the need for a symbol to denote equality. His work in algebra and arithmetic helped standardize mathematical notation in Europe.

罗伯特·雷科德(Robert Recorde):1557 年,雷科德引入等号(

=

=

=),强调需要用特定符号表示“相等”关系。他在代数与算术领域的研究,推动了欧洲数学记法的标准化。

René Descartes: Descartes’s development of Cartesian coordinates and the use of letters to denote variables (x, y, z) and constants (a, b, c) greatly influenced the standardization of algebraic notation. His work in analytic geometry and the use of exponents to represent powers also contributed to the evolution of mathematical symbols.

勒内·笛卡尔(René Descartes):笛卡尔创立笛卡尔坐标系,并使用字母表示变量(

(

x

,

y

,

z

)

(x, y, z)

(x,y,z))与常数(

(

a

,

b

,

c

)

(a, b, c)

(a,b,c)),这对代数记法的标准化产生了深远影响。他在解析几何领域的研究,以及用指数表示幂的方法,也推动了数学符号的演变。

3. Standardization of Mathematical Symbols

3. 数学符号的标准化

17th Century: The 17th century was marked by significant developments in mathematical notation, many of which remain in use today.

17 世纪:17 世纪是数学记法发展的关键时期,当时出现的许多符号至今仍在使用。

Plus (+) and Minus (-) Signs: Johannes Widmann’s arithmetic book in 1489 introduced the plus and minus signs, which became widely adopted over time. These symbols simplified arithmetic operations and became integral to mathematical notation.

加号(

+

+

+)与减号(

−

-

−):1489 年,约翰内斯·维德曼(Johannes Widmann)在其算术著作中引入加号与减号,这些符号逐渐被广泛采用。它们简化了算术运算,成为数学记法的核心组成部分。

Multiplication (×) and Division (÷) Signs: William Oughtred introduced the multiplication sign (×) and Johann Rahn introduced the division sign (÷). These symbols provided a more efficient way to represent arithmetic operations and were widely accepted by the mathematical community.

乘号(

×

\times

×)与除号(

÷

\div

÷):威廉·奥特雷德(William Oughtred)引入乘号(

×

\times

×),约翰·拉恩(Johann Rahn)引入除号(

÷

\div

÷)。这些符号为表示算术运算提供了更高效的方式,得到数学界的广泛认可。

The symbol π: The symbol π, introduced by William Jones in 1706, represents the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter. This symbol, popularized by Leonhard Euler, became standard in mathematical notation for representing this irrational number. Euler’s extensive use of π in his work on mathematical analysis and number theory helped solidify its place in mathematical literature.

圆周率符号(

π

\pi

π):1706 年,威廉·琼斯(William Jones)引入符号

π

\pi

π,用于表示圆的周长与直径之比。该符号经莱昂哈德·欧拉(Leonhard Euler)推广后,成为表示这一无理数的标准数学符号。欧拉在数学分析与数论研究中大量使用

π

\pi

π,进一步巩固了其在数学文献中的地位。

Imaginary Unit (i): The concept of imaginary numbers, which include the square root of -1, was formalized by mathematicians such as Euler and Carl Friedrich Gauss in the 18th century. Euler’s use of the imaginary unit

i

i

i helped in solving equations that had no real solutions and expanded the scope of algebraic analysis.

虚数单位(

i

i

i):包含

−

1

\sqrt{-1}

−1 的虚数概念,在 18 世纪经欧拉(Euler)、卡尔·弗里德里希·高斯(Carl Friedrich Gauss)等数学家形式化。欧拉使用虚数单位

i

i

i,助力求解无实数解的方程,拓展了代数分析的范围。

Infinity (∞): The symbol for infinity (∞) was introduced by John Wallis in 1655. It represents an unbounded quantity and has become a fundamental part of mathematical notation in calculus and set theory.

无穷大符号(

∞

\infty

∞):1655 年,约翰·沃利斯(John Wallis)引入无穷大符号(

∞

\infty

∞),用于表示无界量。该符号如今已成为微积分与集合论中数学记法的基础组成部分。

18th and 19th Centuries

18 世纪与 19 世纪

The 18th and 19th centuries saw further developments in mathematical notation and the introduction of new symbols to accommodate advancing mathematical theories.

18 世纪与 19 世纪,数学记法进一步发展,新符号不断涌现,以适应日益先进的数学理论。

Calculus Notation: Calculus, developed independently by Sir Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, introduced several new notations. Leibniz’s differential (d) and integral (∫) symbols were designed to represent the process of differentiation and integration. Leibniz’s notation, which emphasized the use of symbols and concise expressions, became widely adopted due to its clarity and efficiency.

微积分记法:艾萨克·牛顿爵士(Sir Isaac Newton)与戈特弗里德·威廉·莱布尼茨(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz)各自独立创立微积分,同时引入了多种新记法。莱布尼茨设计的微分符号(

d

d

d)与积分符号(

∫

\int

∫),分别用于表示微分与积分过程。他的记法强调符号使用与表达简洁性,因其清晰高效而被广泛采用。

Summation (Σ) and Product (Π) Notations: Leonhard Euler introduced the summation (Σ) and product (Π) symbols to represent sums and products of sequences. These notations provided a compact way to express long sums and products and have become essential in mathematical analysis and number theory.

求和符号(

Σ

\Sigma

Σ)与乘积符号(

Π

\Pi

Π):莱昂哈德·欧拉(Leonhard Euler)引入求和符号(

Σ

\Sigma

Σ)与乘积符号(

Π

\Pi

Π),分别用于表示数列的和与积。这些记法为表达冗长的和与积提供了简洁方式,如今已成为数学分析与数论的核心符号。

Logical Symbols: The formalization of logic in the 19th century by mathematicians like George Boole and Augustus De Morgan introduced new symbols for logical operations. Boole’s work on Boolean algebra and De Morgan’s laws laid the foundation for modern symbolic logic, using symbols like ∧ (and), ∨ (or), and ∀ (for all).

逻辑符号:19 世纪,乔治·布尔(George Boole)、奥古斯都·德摩根(Augustus De Morgan)等数学家推动逻辑形式化,为逻辑运算引入新符号。布尔在布尔代数领域的研究,以及德摩根定律,为现代符号逻辑奠定了基础,引入了

∧

\land

∧(且)、

∨

\lor

∨(或)、

∀

\forall

∀(对所有)等符号。

4. 20th Century and Modern Standardization

4. 20 世纪与现代标准化

Set Theory and Logic: The development of set theory and formal logic in the 20th century led to the creation and standardization of various mathematical symbols.

集合论与逻辑:20 世纪,集合论与形式逻辑的发展推动了多种数学符号的创造与标准化。

Set Theory: Georg Cantor’s development of set theory introduced symbols like ∈ (element of), ⊆ (subset), and ∅ (empty set). Cantor’s work on the concept of infinity and cardinality revolutionized the understanding of mathematical sets and paved the way for modern mathematical theory.

集合论:格奥尔格·康托尔(Georg Cantor)创立集合论,引入属于符号(

∈

\in

∈)、子集符号(

⊆

\subseteq

⊆)和空集符号(

∅

\emptyset

∅)。他在无穷概念与基数理论方面的研究,彻底革新了对数学集合的理解,为现代数学理论奠定了基础。

Formal Logic: Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead’s work on symbolic logic in Principia Mathematica (1910-1913) expanded the use of logical symbols. Their work aimed to formalize mathematical logic and provide a rigorous foundation for mathematics using symbols and logical notation.

形式逻辑:伯特兰·罗素(Bertrand Russell)与阿尔弗雷德·诺思·怀特海(Alfred North Whitehead)在《数学原理》(Principia Mathematica,1910-1913 年)中对符号逻辑的研究,拓展了逻辑符号的应用。他们的研究旨在将数学逻辑形式化,通过符号与逻辑记法为数学提供严谨基础。

Typography and Publishing

排版与出版

The advent of printing and later digital typesetting played a crucial role in the standardization of mathematical notation.

印刷术的发明以及后续数字排版技术的发展,对数学记法的标准化起到了关键作用。

Printing Press: The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century made it easier to reproduce mathematical texts and notation. This contributed to the dissemination of standardized symbols and formulas across Europe.

印刷机:15 世纪,约翰内斯·谷登堡(Johannes Gutenberg)发明印刷机,使数学文献与记法的复制更为便捷。这推动了标准化符号与公式在欧洲的传播。

Digital Typesetting: The development of digital typesetting systems, such as TeX and LaTeX, revolutionized the presentation of mathematical notation. LaTeX, developed by Leslie Lamport in the 1980s, became the standard for typesetting mathematical documents, ensuring consistent and precise notation in academic papers and books.

数字排版:TeX、LaTeX 等数字排版系统的发展,彻底革新了数学记法的呈现方式。20 世纪 80 年代,莱斯利·兰波特(Leslie Lamport)开发的 LaTeX,成为数学文档排版的标准工具,确保学术论文与书籍中数学记法的一致性与精准性。

International Standards

国际标准

International organizations have worked to standardize mathematical notation to facilitate global communication and collaboration.

国际组织致力于数学记法的标准化,以促进全球范围内的交流与合作。

ISO: The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has developed standards for various aspects of mathematical notation and terminology. These standards aim to ensure consistency and clarity in mathematical communication across different countries and disciplines.

国际标准化组织(ISO):国际标准化组织(ISO)针对数学记法与术语的多个方面制定了标准。这些标准旨在确保不同国家、不同学科间数学交流的一致性与清晰度。

IMU: The International Mathematical Union (IMU) plays a key role in promoting international cooperation and standardization in mathematics. The IMU works on various aspects of mathematical research, including the development and standardization of mathematical notation.

国际数学联盟(IMU):国际数学联盟(IMU)在推动数学领域国际合作与标准化方面发挥关键作用。该联盟致力于数学研究的多个领域,包括数学记法的发展与标准化。

Digital and Computational Tools

数字与计算工具

The rise of digital and computational tools has influenced modern mathematical notation.

数字与计算工具的兴起,对现代数学记法产生了深远影响。

Computer Algebra Systems (CAS): Tools like Mathematica and Maple have introduced new notations and conventions to accommodate computational needs. These systems often use specialized symbols and syntax to represent mathematical operations and functions.

计算机代数系统(CAS):Mathematica、Maple 等工具为满足计算需求,引入了新记法与新规则。这些系统通常使用专用符号与语法表示数学运算与函数。

Programming Languages: Languages such as Python and R have incorporated mathematical notation into their syntax, allowing for efficient implementation of mathematical algorithms and operations.

编程语言:Python、R 等编程语言将数学记法融入其语法,支持数学算法与运算的高效实现。

Cross-disciplinary Integration: As mathematics intersects with fields like computer science, physics, and engineering, new notations and conventions are developed to address specific needs. This integration often leads to the creation of new symbols and notation systems to represent complex concepts.

跨学科融合:随着数学与计算机科学、物理学、工程学等领域的交叉融合,为满足特定需求,新记法与新规则不断涌现。这种融合通常会催生新符号与新记法体系,用于表示复杂概念。

CONCLUSION:

结论:

The evolution of mathematical notation and symbols is a testament to the progressive nature of mathematical thought and its role in facilitating global communication. From the early numeral systems of ancient civilizations to the sophisticated symbols used in modern mathematics, this evolution reflects the increasing complexity and precision required in mathematical discourse. Key milestones, such as the adoption of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, the formalization of algebraic and calculus notations, and the standardization efforts of the 19th and 20th centuries, have been pivotal in shaping the way mathematical concepts are expressed and understood.

数学符号与记法的演变,印证了数学思想的渐进性及其在促进全球交流中的作用。从古代文明的早期数字系统,到现代数学中的精密符号,这一演变反映了数学表达对复杂性与精准性的要求不断提升。印度-阿拉伯数字系统的采用、代数与微积分记法的形式化、19 至 20 世纪的标准化努力等关键里程碑,对数学概念的表达与理解方式产生了决定性影响。

The development of standardized symbols has enabled clearer communication and collaboration across different regions and disciplines, while the integration of digital tools continues to influence and expand mathematical notation. As mathematics advances and intersects with other fields, the notation system will likely adapt to meet new challenges and opportunities. Overall, the history of mathematical notation underscores its essential role in the progression of mathematical knowledge, demonstrating how a shared language can advance understanding and innovation in the scientific and mathematical communities.

标准化符号的发展,实现了跨地区、跨学科更清晰的交流与合作;而数字工具的融合,持续影响并拓展着数学记法。随着数学的发展及其与其他领域的交叉融合,记法体系将不断调整以应对新挑战、把握新机遇。总体而言,数学记法的历史凸显了其在数学知识发展中的核心作用,证明了一套通用语言能够推动科学界与数学界的认知进步与创新。

REFERENCES:

参考文献:

-

Bell, E. T. (1937). Men of mathematics. Simon and Schuster.

贝尔(Bell, E. T.). (1937). 《数学家们》(Men of Mathematics). 西蒙与舒斯特出版社(Simon and Schuster). -

Euler, L. (2003). Leonhard Euler: Mathematical works (Vol. 1). Springer. (Original works published 18th century)

欧拉(Euler, L.). (2003). 《莱昂哈德·欧拉数学著作集》(第 1 卷)(Leonhard Euler: Mathematical works, Vol. 1). 斯普林格出版社(Springer).(原著出版于 18 世纪) -

Katz, V. J. (1998). A history of mathematics: An introduction (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

卡茨(Katz, V. J.). (1998). 《数学史导论》(第 3 版)(A history of mathematics: An introduction, 3rd ed.). 艾迪生-韦斯利出版社(Addison-Wesley). -

Kline, M. (1980). Mathematics: The loss of certainty. Oxford University Press.

克莱因(Kline, M.). (1980). 《数学:确定性的丧失》(Mathematics: The loss of certainty). 牛津大学出版社(Oxford University Press). -

Swetz, F. J. (2003). The mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A sourcebook. Princeton University Press.

斯韦茨(Swetz, F. J.). (2003). 《埃及、美索不达米亚、中国、印度与伊斯兰世界的数学:史料集》(The mathematics of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, India, and Islam: A sourcebook). 普林斯顿大学出版社(Princeton University Press).

数学符号历史演变参考表

一、代数与算术符号

| 符号 | 历史演变关键阶段 | 关键人物 / 文明 | 时间节点 | 核心事件 / 意义 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| = = =(等号) | 1. 早期用文字表述 “相等”; 2. 提出平行线符号; 3. 地区性符号竞争; 4. 全球标准化 | 罗伯特・雷科德(Robert Recorde)、笛卡尔、莱布尼茨 | 1540 年(开始使用)、1557 年(著作正式提出)、17 世纪(普及) | 雷科德以 “两条等长平行线” 表示相等,击败笛卡尔的 α \alpha α、莱布尼茨的楔形符号,成为通用符号 |

| 0 0 0(零) | 1. 空白表示 “零” 概念; 2. 符号化初步发展; 3. 跨文明传播; 4. 推动位值制与代数运算 | 巴比伦数学家、印度数学家、阿拉伯学者、欧洲数学家 | 公元前(巴比伦)、公元 3-5 世纪(印度符号化)、12-16 世纪(欧洲普及) | 巴比伦用空白表 “零”,印度人首创 0 0 0 符号,经阿拉伯传入欧洲,推动位值制计数法和代数运算发展,人类学家仍在探寻最早铭文 |

| + + +(加号) | 1. 拉丁文 “et”(“和”)缩写; 2. 草写 “μ” 演变; 3. 印刷术推动标准化 | 尼科尔・奥雷姆、约翰内斯・魏德曼(Johannes Widmann)、荷伊克 | 1360 年(近似,“et” 缩写)、1489 年(魏德曼著作使用)、1514 年(荷伊克推广) | 从拉丁文 “et” 演变,魏德曼首次在印刷品中使用,荷伊克推动其成为公认符号,击败意大利 “p” 符号 |

| − - −(减号) | 1. 拉丁文 “minus”(“减”)缩写 “m”; 2. 省略字母成 “-”;3. 与加号同步普及 | 约翰内斯・魏德曼、荷伊克 | 1489 年(魏德曼著作使用)、1514 年(荷伊克推广) | 从 “minus” 缩写演变,最初也用于酒桶计数(标记酒的减少),后与加号共同成为全球通用运算符号 |

| × \times ×(乘号) | 1. 提出 “×” 符号; 2. 竞争 “・” 符号; 3. 确立双符号并行体系 | 威廉・奥屈特(William Oughtred)、莱布尼茨 | 1631 年(奥屈特提出 “×”)、17 世纪(莱布尼茨推广 “・”) | 奥屈特首创 “×”,莱布尼茨推广 “・” 以避免与字母 “x” 混淆,赫锐奥特曾用 “ab” 表乘法,最终 “×” 与 “・” 并行使用 |

| ÷ \div ÷(除号) | 1. 早期用 “:” 或分数线; 2. 首创 “÷” 符号; 3. 正式纳入代数符号体系 | 威廉・奥屈特、约翰・拉恩(Johann Rahn) | 1631 年(奥屈特用 “:” 表除)、1659 年(拉恩创 “÷” 并推广) | 拉恩以 “横线分两圆点” 表 “平均分”,后经他在《代数学》中推广,成为通用除号 |

| \sqrt {} (根号) | 1. 古埃及有求根概念和方法;2. 德国小点演变; 3. 鲁道夫引入现代根号; 4. 笛卡尔标准化 | 古埃及数学家、克里斯托弗・鲁道夫(Christoff Rudolff)、笛卡尔 | 公元前(古埃及求根概念)、1525 年(鲁道夫《Coss》使用)、1637 年(笛卡尔《方法论》确立) | 从拉丁文 “radix”(根)首字母演变,笛卡尔统一符号为 “√ ̄”,解决复杂方程表达问题 |

| % \% %(百分号) | 1. 意大利 “per cento” 缩写 “pc”; 2. 符号简化为 “%”; 3. 商业与统计领域普及 | 意大利商人、欧洲数学家 | 15 世纪(缩写雏形)、17 世纪(符号定型) | 源于意大利语 “每百”,通过印刷术简化为 “%”,成为全球通用的百分比表示符号 |

二、几何与三角符号

| 符号 | 历史演变关键阶段 | 关键人物 / 文明 | 时间节点 | 核心事件 / 意义 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| π \pi π(圆周率) | 1. 古文明近似值计算; 2. 符号 π \pi π 首次使用; 3. 欧拉推广为标准符号 | 阿基米德、威廉・琼斯(William Jones)、欧拉 | 公元前 250 年(阿基米德计算)、1706 年(琼斯首次使用)、1736 年(欧拉标准化) | 源于希腊语 “περιφέρεια”(圆周)首字母,欧拉确立其为圆周率专用符号,推动数学分析发展 |

| ∠ \angle ∠(角) | 1. 古希腊用文字或字母组合表示角; 2. 符号简化为 “∠”; 3. 现代几何符号体系确立 | 古希腊数学家、欧洲数学家 | 公元前 300 年(欧几里得《几何原本》文字描述)、16 世纪(符号简化) | 从早期文字描述(如 “∠BAC”)演变,经文艺复兴时期简化为 “∠”,通过形态直观性成为几何图形的标准符号 |

| ⊥ \perp ⊥(垂直) | 1. 古希腊文字描述; 2. 符号 “⊥” 首次出现; 3. 纳入欧几里得几何体系 | 欧几里得、欧洲数学家 | 公元前 300 年(文字描述)、17 世纪(符号定型) | 源于拉丁语 “perpendicularis”(垂直),符号 “⊥” 直观表示两条直线的垂直关系 |

| ∥ \parallel ∥(平行) | 1. 古希腊文字描述; 2. 符号 “∥” 首次出现; 3. 与等号符号的竞争与分化 | 欧几里得、欧洲数学家 | 公元前 300 年(文字描述)、17 世纪(符号定型) | 源于拉丁语 “parallelus”(平行),符号 “∥” 通过形态相似性与等号区分,成为几何专用符号 |

三、微积分与分析符号

| 符号 | 历史演变关键阶段 | 关键人物 | 时间节点 | 核心事件 / 意义 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∑ \sum ∑(求和符号) | 1. 古希腊累加概念; 2. 欧拉引入 ∑ \sum ∑ 符号; 3. 成为级数运算标准符号 | 欧拉(Leonhard Euler) | 1755 年(首次使用) | 源于拉丁文 “summa”(总和)的希腊大写字母 Sigma( Σ \Sigma Σ),欧拉将其标准化为 ∑ \sum ∑,简化无穷级数表达 |

| ∫ \int ∫(积分符号) | 1. 莱布尼茨引入 “∫” 符号; 2. 牛顿流数符号竞争; 3. 莱布尼茨符号全球普及 | 莱布尼茨(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz) | 1675 年(首次使用) | 源于拉丁文 “summa”(总和)的首字母拉长,莱布尼茨用 “∫” 表示积分,成为微积分核心符号 |

| d y / d x dy/dx dy/dx(导数符号) | 1. 莱布尼茨引入微分符号 “dx”“dy”; 2. 导数符号 “dy/dx” 定型; 3. 偏导数符号 ∂ \partial ∂ 出现 | 莱布尼茨、雅可比(Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi) | 1675 年(微分符号)、1841 年(偏导数符号) | 莱布尼茨用 “d” 表示微分,雅可比引入 ∂ \partial ∂ 区分偏导数,形成现代微积分符号体系 |

| ∂ \partial ∂(偏导数符号) | 1. 孔多塞尝试表示 “偏差”; 2. 勒让德提出类似符号; 3. 雅可比标准化推广; 4. 跨学科应用 | 孔多塞、勒让德、雅可比 | 1770 年(孔多塞尝试)、1786 年(勒让德使用)、1841 年(雅可比标准化) | 为 “d” 的草书写法变体,强调 “局部变化”,雅可比通过雅可比矩阵确立其地位,现用于流体力学、机器学习等领域 |

| ∇ \nabla ∇(梯度符号) | 1. 哈密顿引入 “∇” 符号; 2. 确定 “纳布拉(Nabla)” 名称; 3. 麦克斯韦推动场论应用; 4. 量子力学普及 | 哈密顿、威廉・罗伯逊・史密斯、麦克斯韦 | 1831 年(哈密顿引入)、1870 年(名称确定)、19 世纪末(场论应用) | 形似古腓尼基竖琴 “纳布拉”,定义为向量微分算子,麦克斯韦用于电磁方程,现支撑航空航天数值模拟 |

| e e e(自然常数) | 1. 伯努利复利研究; 2. 欧拉命名并推广; 3. 成为指数函数底数 | 雅各布・伯努利(Jacob Bernoulli)、欧拉 | 1683 年(伯努利发现)、1731 年(欧拉命名) | 源于复利计算的极限,欧拉用 “e” 表示自然常数,推动数学分析与物理学发展 |

| ∞ \infty ∞(无穷大) | 1. 古希腊哲学概念; 2. 沃利斯引入 “∞” 符号; 3. 数学分析中严格定义 | 约翰・沃利斯(John Wallis)、魏尔斯特拉斯(Karl Weierstrass) | 1655 年(沃利斯使用)、19 世纪(严格定义) | 符号形似横放的 “8”,沃利斯用于表示无穷大,后经魏尔斯特拉斯纳入极限理论体系 |

四、集合论与逻辑符号

| 符号 | 历史演变关键阶段 | 关键人物 | 时间节点 | 核心事件 / 意义 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∈ \in ∈(属于) | 1. 皮亚诺引入符号 “∈”; 2. 源于希腊字母 “ε”; 3. 集合论基础符号确立 | 朱塞佩・皮亚诺(Giuseppe Peano) | 1889 年(首次使用) | 源于希腊语 “ἐστί”(是)首字母,皮亚诺用 “∈” 表示元素与集合的关系,成为集合论基石 |

| ∪ \cup ∪(并集) | 1. 施罗德引入符号 “∪”; 2. 源于拉丁语 “union”; 3. 布尔代数符号体系完善 | 恩斯特・施罗德(Ernst Schröder) | 1890 年(首次使用) | 符号 “∪” 通过形态相似性表示集合合并,成为布尔代数与集合论的标准符号 |

| ∩ \cap ∩(交集) | 1. 施罗德引入符号 “∩”; 2. 源于拉丁语 “intersectio”; 3. 与并集符号对称设计 | 恩斯特・施罗德(Ernst Schröder) | 1890 年(首次使用) | 符号 “∩” 通过倒置的 “∪” 表示集合交集,与并集形成对称体系,简化集合运算表达 |

| ∀ \forall ∀(全称量词) | 1. 根岑引入符号 “∀”; 2. 倒写字母 “A”; 3. 数理逻辑符号体系确立 | 格哈德・根岑(Gerhard Gentzen) | 20 世纪初(首次使用) | 源于德语 “Alle”(所有)或英语 “All” 的首字母倒写,根岑用倒写 “A” 表示全称量词,成为谓词逻辑核心符号 |

| ∃ \exists ∃(存在量词) | 1. 根岑引入符号 “∃”; 2. 倒写字母 “E”; 3. 与全称量词对称设计 | 格哈德・根岑(Gerhard Gentzen) | 20 世纪初(首次使用) | 源于德语 “Existenz”(存在)或英语 “Exists” 的首字母倒写,根岑用倒写 “E” 表示存在量词,与全称量词形成逻辑对偶 |

五、特殊常数与其他符号

| 符号 | 历史演变关键阶段 | 关键人物 | 时间节点 | 核心事件 / 意义 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| i i i(虚数单位) | 1. 邦贝利提出复数概念; 2. 笛卡尔创造 “虚数” 一词; 3. 欧拉命名 “i”;4. 复数理论完善 | 拉斐尔・邦贝利(Rafael Bombelli)、笛卡尔、欧拉 | 1572 年(邦贝利提出复数)、1637 年(笛卡尔提出 “虚数”)、1777 年(欧拉命名 “i”) | 源于笛卡尔提出的 “imaginarius”(想象的)概念,欧拉用其首字母 “i” 表示虚数单位,推动复分析发展 |

| ≈ \approx ≈(约等于) | 1. 早期波浪线表示近似; 2. 符号标准化为 “≈”; 3. 科学计算与工程领域普及 | 欧洲数学家 | 18 世纪(符号定型) | 源于拉丁文 “approximatus”(近似),符号 “≈” 通过形态直观性表示数值接近关系 |

数学符号发展关键里程碑

| 时期 | 关键符号 / 记法 | 贡献者 / 文明 | 意义 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 古代文明(约公元前 2000 年 - 公元 5 世纪) | 古埃及象形数字(基于 10 的幂) | 古埃及文明 | 满足土地测量、资源分配等实际需求,构建早期数字表示体系 |

| 古巴比伦六十进制(base-60)数字系统 | 古巴比伦文明 | 引入位值思想,至今用于时间(时 / 分 / 秒)和角度(度 / 分 / 秒)测量 | |

| 古希腊文字记法(修辞 notation)、字母表示特定量 | 古希腊(毕达哥拉斯、欧几里得、丢番图) | 从 “文字表达数学" 向 “符号化" 过渡,丢番图用符号表示未知数,奠定代数记法基础 | |

| 罗马数字(I, V, X, L, C, D, M) | 古罗马文明 | 适用于贸易记录与基础算术,成为中世纪欧洲主要数字系统 | |

| 6 世纪 - 12 世纪 | 印度 - 阿拉伯数字系统(含 “零" 与位值记法) | 印度(婆罗摩笈多、阿耶波多)、阿拉伯(Al-Khwarizmi) | 数学记法革命性突破,简化复杂计算,逐步取代罗马数字成为主流 |

| 伊斯兰黄金时代(8-14 世纪) | 系统性代数解题方法(文字叙述形式) | 伊斯兰数学家(Al-Khwarizmi、Al-Kindi) | 为代数符号化奠定理论基础,推动代数从 “实用计算" 向 “理论体系" 发展 |

| 文艺复兴时期(欧洲,16 世纪) | 字母表示已知 / 未知量、等号(=)、笛卡尔坐标系 | 弗朗索瓦・韦达、罗伯特・雷科德、勒内・笛卡尔 | 韦达标准化 “字母表记法";雷科德 1557 年引入等号;笛卡尔定义变量(x,y,z)与常数(a,b,c),奠定现代代数与解析几何记法 |

| 17-18 世纪 | 加号(+)、减号(-) | 约翰内斯・维德曼(1489 年) | 简化算术运算表达,成为数学符号体系的基础运算符号 |

| 乘号(×)、除号(÷) | 威廉・奥特雷德、约翰・拉恩 | 规范乘法与除法的符号表达,提升运算记法效率 | |

| 圆周率(π)、虚数单位(i)、无穷大(∞) | 威廉・琼斯(π)、欧拉(i, π 推广)、约翰・沃利斯(∞) | π 成为圆周长与直径比的标准符号;i 拓展代数分析范围;∞为微积分与集合论提供核心符号 | |

| 微积分符号(微分 d、积分∫)、求和(Σ)、乘积(Π) | 莱布尼茨(微积分)、欧拉(Σ, Π) | 莱布尼茨记法因清晰高效成为微积分标准;Σ 与 Π 实现 “冗长序列运算" 的简洁表达 | |

| 19 世纪 | 逻辑符号(∧“且"、∨“或"、∀“对所有") | 乔治・布尔、奥古斯都・德摩根 | 推动逻辑形式化,为现代符号逻辑与计算机科学奠定基础 |

| 集合论符号(∈“属于"、⊆“子集"、∅“空集") | 格奥尔格・康托尔 | 规范集合概念的符号表达,革新数学基础理论,支撑现代数学体系构建 | |

| 20 世纪 | 数字排版系统(TeX/LaTeX) | 莱斯利・兰波特(LaTeX) | 实现数学符号的精准、统一排版,成为学术论文与书籍的标准记法工具 |

| 数学符号国际标准 | 国际标准化组织(ISO)、国际数学联盟(IMU) | 确保跨国家、跨学科的数学符号一致性,促进全球数学交流与合作 | |

| 计算工具专用符号(CAS 系统、编程语言语法) | Mathematica/Maple(CAS)、Python/R(编程语言) | 适配数字计算需求,推动数学符号与计算机科学、工程学等领域的跨学科融合 |

符号发展规律

1.抽象化进程:从象形文字(如古埃及

\sqrt {}

雏形 “┌”)到纯符号(如

∞

\infty

∞),数学表达不断脱离具体实物,转向抽象逻辑。

2.标准化竞争:同一概念常出现多种符号(如等号

=

=

= vs 笛卡尔

α

\alpha

α),最终通过学术权威(如欧拉、莱布尼茨)或印刷术普及形成全球共识。

3.文化融合:符号传播跨越文明(如印度

0

0

0 经阿拉伯传入欧洲),体现数学作为通用语言的特性。

4.功能分化:符号设计兼顾简洁性与区分度(如

∪

\cup

∪ 与

∩

\cap

∩ 的对称设计),避免与其他符号混淆。

via:

-

Mathematical Symbols’ Wild History Explained | Scientific American

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mathematical-symbols-wild-history-explained/ -

Mathematical Notation And Symbols: History And Standardization - IJRAR19D6223.pdf .

https://ijrar.org/papers/IJRAR19D6223.pdf

1653

1653

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?