注:本文为 “微积分 | dy / dx” 相关讨论辨析。

英文引文,机翻未校。

如有内容异常,请看原文。

Is d y d x \frac{dy}{dx} dxdy not a ratio?

d y d x \frac{dy}{dx} dxdy 不是比率吗?

In the book Thomas’s Calculus (11th edition) it is mentioned (Section 3.8 pg 225) that the derivative

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is not a ratio. Couldn’t it be interpreted as a ratio, because according to the formula

d

y

=

f

′

(

x

)

d

x

dy = f'(x)dx

dy=f′(x)dx we are able to plug in values for

d

x

dx

dx and calculate a

d

y

dy

dy (differential). Then if we rearrange we get

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy which could be seen as a ratio.

在《托马斯微积分》(第 11 版)中提到(第 3.8 节第 225 页),导数

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 不是一个比率。但它难道不能被解释为比率吗?因为根据公式

d

y

=

f

′

(

x

)

d

x

dy = f'(x)dx

dy=f′(x)dx,我们可以代入

d

x

dx

dx 的值并计算出

d

y

dy

dy(微分)。然后,如果我们重新整理,就得到

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy,这看起来就像一个比率。

I wonder if the author say this because

d

x

dx

dx is an independent variable, and

d

y

dy

dy is a dependent variable, for

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy to be a ratio both variables need to be independent… maybe?

我想知道作者这么说是不是因为

d

x

dx

dx 是自变量,而

d

y

dy

dy 是因变量,要让

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 成为比率,两个变量都需要是独立的……或许是这样?

edited Oct 1, 2023 at 5:57

11pro12

asked Feb 9, 2011 at 16:23

BBSysDyn

It may be of interest to record Russell’s views of the matter: “Leibniz’s belief that the Calculus had philosophical importance is now known to be erroneous: there are no infinitesimals in it, and

d

x

dx

dx and

d

y

dy

dy are not numerator and denominator of a fraction.” (Bertrand Russell, RECENT WORK ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF LEIBNIZ. Mind, 1903).

或许有必要记录一下罗素对此事的观点:“莱布尼茨认为微积分具有哲学重要性的看法如今被证实是错误的:微积分中不存在无穷小量,且

d

x

dx

dx 和

d

y

dy

dy 也不是分数的分子和分母。”(伯特兰·罗素,《关于莱布尼茨哲学的近期研究》,《心灵》杂志,1903 年)。

– Mikhail Katz

Commented May 1, 2014 at 17:10

So yet another error made by Russell, is what you’re saying?

所以你是说,这是罗素犯的又一个错误?

– Toby Bartels

Commented Apr 29, 2017 at 4:24

It can be roughly interpreted as a rate of change of

y

y

y as a function of

x

x

x. This statement though has many lacks.

它可以粗略地解释为

y

y

y 作为

x

x

x 的函数的变化率。不过这个表述有很多不足。

– user405599

Commented Aug 28, 2017 at 17:39

Obviously it is a ratio! You can tell by the fact that

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy

is obtained with \frac{dy}{dx}, and frac is for “fraction”. (I am joking.)

显然它是一个比率!你可以从这一点看出来:

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是用 \frac{dy}{dx} 得到的,而 frac 代表“分数”。(我是在开玩笑。)

– Galen

Commented Oct 10, 2022 at 4:04

27 Answers

Historically, when Leibniz conceived of the notation,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy was supposed to be a quotient: it was the quotient of the “infinitesimal change in

y

y

y produced by the change in

x

x

x” divided by the “infinitesimal change in

x

x

x”.

从历史上看,当莱布尼茨构思这一符号时,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 本应是一个商:它是“由

x

x

x 的变化所产生的

y

y

y 的无穷小变化”除以“

x

x

x 的无穷小变化”的商。

However, the formulation of calculus with infinitesimals in the usual setting of the real numbers leads to a lot of problems. For one thing, infinitesimals can’t exist in the usual setting of real numbers! Because the real numbers satisfy an important property, called the Archimedean Property: given any positive real number

ϵ

>

0

\epsilon > 0

ϵ>0, no matter how small, and given any positive real number

M

>

0

M > 0

M>0, no matter how big, there exists a natural number

n

n

n such that

n

ϵ

>

M

n\epsilon > M

nϵ>M. But an “infinitesimal”

ξ

\xi

ξ is supposed to be so small that no matter how many times you add it to itself, it never gets to

1

1

1, contradicting the Archimedean Property. Other problems: Leibniz defined the tangent to the graph of

y

=

f

(

x

)

y = f(x)

y=f(x) at

x

=

a

x = a

x=a by saying “Take the point

(

a

,

f

(

a

)

)

(a, f(a))

(a,f(a)); then add an infinitesimal amount to

a

a

a,

a

+

d

x

a + dx

a+dx, and take the point

(

a

+

d

x

,

f

(

a

+

d

x

)

)

(a + dx, f(a + dx))

(a+dx,f(a+dx)), and draw the line through those two points.” But if they are two different points on the graph, then it’s not a tangent, and if it’s just one point, then you can’t define the line because you just have one point. That’s just two of the problems with infinitesimals. (See below where it says “However…”, though.)

然而,在实数的常规设定中用无穷小量来构建微积分会带来很多问题。首先,在实数的常规设定中,无穷小量不可能存在!因为实数满足一个重要性质,称为阿基米德性质:对于任意正实数

ϵ

>

0

\epsilon > 0

ϵ>0(无论多么小),以及任意正实数

M

>

0

M > 0

M>0(无论多么大),都存在一个自然数

n

n

n,使得

n

ϵ

>

M

n\epsilon > M

nϵ>M。但“无穷小量”

ξ

\xi

ξ 被认为是如此之小,以至于无论你把它自身加多少次,它都永远到不了

1

1

1,这与阿基米德性质相矛盾。其他问题:莱布尼茨这样定义

y

=

f

(

x

)

y = f(x)

y=f(x) 的图像在

x

=

a

x = a

x=a 处的切线:“取点

(

a

,

f

(

a

)

)

(a, f(a))

(a,f(a));然后给

a

a

a 加上一个无穷小量,得到

a

+

d

x

a + dx

a+dx,再取点

(

a

+

d

x

,

f

(

a

+

d

x

)

)

(a + dx, f(a + dx))

(a+dx,f(a+dx)),并画出经过这两个点的直线。” 但如果这是图像上的两个不同点,那么它就不是切线;而如果它只是一个点,那么你无法定义这条直线,因为你只有一个点。这只是无穷小量带来的两个问题(不过,参见下文“然而……”部分)。

So Calculus was essentially rewritten from the ground up in the following 200 years to avoid these problems, and you are seeing the results of that rewriting (that’s where limits came from, for instance). Because of that rewriting, the derivative is no longer a quotient, now it’s a limit:

因此,在接下来的 200 年里,为了避免这些问题,微积分基本上被彻底重写,而你所看到的就是这次重写的结果(例如,极限就源于此)。由于这次重写,导数不再是一个商,而是一个极限:

lim h → 0 f ( x + h ) − f ( x ) h \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h} limh→0hf(x+h)−f(x).

And because we cannot express this limit-of-a-quotient as a-quotient-of-the-limits (both numerator and denominator go to zero), then the derivative is not a quotient.

而且,因为我们不能将这个“商的极限”表示为“极限的商”(分子和分母都趋向于零),所以导数不是一个商。

However, Leibniz’s notation is very suggestive and very useful; even though derivatives are not really quotients, in many ways they behave as if they were quotients. So we have the Chain Rule:

然而,莱布尼茨的符号非常具有启发性且非常有用;尽管导数并非真正的商,但在很多方面它们的表现就好像是商一样。所以我们有链式法则:

d y d x = d y d u d u d x \frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{dy}{du} \frac{du}{dx} dxdy=dudydxdu

which looks very natural if you think of the derivatives as “fractions”. You have the Inverse Function theorem, which tells you that

如果你把导数看作“分数”,这看起来就非常自然。你还知道反函数定理,它告诉你:

d x d y = 1 d y d x \frac{dx}{dy} = \frac{1}{\frac{dy}{dx}} dydx=dxdy1,

which is again almost “obvious” if you think of the derivatives as fractions. So, because the notation is so nice and so suggestive, we keep the notation even though the notation no longer represents an actual quotient, it now represents a single limit. In fact, Leibniz’s notation is so good, so superior to the prime notation and to Newton’s notation, that England fell behind all of Europe for centuries in mathematics and science because, due to the fight between Newton’s and Leibniz’s camp over who had invented Calculus and who stole it from whom (consensus is that they each discovered it independently), England’s scientific establishment decided to ignore what was being done in Europe with Leibniz notation and stuck to Newton’s… and got stuck in the mud in large part because of it.

如果你把导数看作分数,这一点也几乎是“显而易见”的。因此,由于这个符号非常精妙且具有启发性,我们保留了它,尽管它不再代表实际的商,而是代表一个单一的极限。事实上,莱布尼茨的符号非常出色,优于撇号符号和牛顿的符号,以至于英国在数学和科学领域落后于欧洲各国数个世纪——因为牛顿阵营和莱布尼茨阵营就谁发明了微积分以及谁从谁那里窃取了微积分的成果发生了争执(共识是他们各自独立发现了微积分),英国的科学界决定忽视欧洲大陆使用莱布尼茨符号所做的研究,坚持使用牛顿的符号……而在很大程度上因此陷入了困境。

(Differentials are part of this same issue: originally,

d

y

dy

dy and

d

x

dx

dx really did mean the same thing as those symbols do in

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy, but that leads to all sorts of logical problems, so they no longer mean the same thing, even though they behave as if they did.)

(微分也属于同一个问题:最初,

d

y

dy

dy 和

d

x

dx

dx 的含义与它们在

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 中的含义确实相同,但这会导致各种逻辑问题,所以它们不再具有相同的含义,尽管它们的表现好像仍有相同含义一样。)

So, even though we write

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as if it were a fraction, and many computations look like we are working with it like a fraction, it isn’t really a fraction (it just plays one on television).

所以,尽管我们把

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 写成好像是一个分数的样子,而且很多计算看起来就像我们在把它当作分数来处理,但它并非真正的分数(它只是在“电视上”扮演分数的角色)。

However… There is a way of getting around the logical difficulties with infinitesimals; this is called nonstandard analysis. It’s pretty difficult to explain how one sets it up, but you can think of it as creating two classes of real numbers: the ones you are familiar with, that satisfy things like the Archimedean Property, the Supremum Property, and so on, and then you add another, separate class of real numbers that includes infinitesimals and a bunch of other things. If you do that, then you can, if you are careful, define derivatives exactly like Leibniz, in terms of infinitesimals and actual quotients; if you do that, then all the rules of Calculus that make use of

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as if it were a fraction are justified because, in that setting, it is a fraction. Still, one has to be careful because you have to keep infinitesimals and regular real numbers separate and not let them get confused, or you can run into some serious problems.

然而…… 有一种方法可以避开无穷小量带来的逻辑困难,这就是所谓的非标准分析。解释它的构建方式相当困难,但你可以把它理解为创建了两类实数:一类是你熟悉的,满足阿基米德性质、上确界性质等;然后你再添加另一类独立的实数,其中包括无穷小量和其他一些东西。如果这样做,并且足够谨慎,你就可以像莱布尼茨那样,完全用无穷小量和实际的商来定义导数;在这种情况下,所有将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 当作分数来使用的微积分规则都是合理的,因为在这种设定中,它确实是一个分数。不过,必须要小心,因为你必须将无穷小量和常规实数区分开来,不能混淆,否则会遇到严重的问题。

edited Sep 15, 2017 at 20:01

answered Feb 9, 2011 at 17:05

Arturo Magidin

As a physicist, I prefer Leibniz notation simply because it is dimensionally correct regardless of whether it is derived from the limit or from nonstandard analysis. With Newtonian notation, you cannot automatically tell what the units of

y

′

y'

y′ are.

作为一名物理学家,我更喜欢莱布尼茨符号,原因很简单,无论它是从极限还是从非标准分析中推导出来的,它在量纲上都是正确的。而用牛顿符号,你无法直接看出

y

′

y'

y′ 的单位是什么。

– rcollyer

Commented Mar 10, 2011 at 16:34

Have you any evidence for your claim that “England fell behind Europe for centuries”?

你声称“英国落后欧洲数个世纪”,有什么证据吗?

– Kevin H. Lin

Commented Mar 21, 2011 at 22:05

@Kevin: Look at the history of math. Shortly after Newton and his students (Maclaurin, Taylor), all the developments in mathematics came from the Continent. It was the Bernoullis, Euler, who developed Calculus, not the British. It wasn’t until Hamilton that they started coming back, and when they reformed math teaching in Oxford and Cambridge, they adopted the continental ideas and notation.

@凯文:看看数学史。在牛顿及其学生(麦克劳林、泰勒)之后不久,数学领域的所有发展都来自欧洲大陆。是伯努利家族、欧拉等人发展了微积分,而不是英国人。直到哈密顿时期,英国才开始有所起色,当他们改革牛津和剑桥的数学教学时,才采用了欧洲大陆的思想和符号。

– Arturo Magidin

Commented Mar 22, 2011 at 1:42

Mathematics really did not have a firm hold in England. It was the Physics of Newton that was admired. Unlike in parts of the Continent, mathematics was not thought of as a serious calling. So the “best” people did other things.

数学在英国确实没有牢固的地位。人们推崇的是牛顿的物理学。与欧洲大陆的部分地区不同,数学并没有被视为一种严肃的职业。所以,那些“最优秀”的人去做了其他事情。

– André Nicolas

Commented Jun 20, 2011 at 19:02

There’s a free calculus textbook for beginning calculus students based on the nonstandard analysis approach here. Also there is a monograph on infinitesimal calculus aimed at mathematicians and at instructors who might be using the aforementioned book.

这里有一本基于非标准分析方法的面向微积分初学者的免费教材。还有一本关于无穷小微积分的专著,面向数学家以及可能使用上述教材的教师。

– tzs

Commented Jul 6, 2011 at 16:24

Just to add some variety to the list of answers, I’m going to go against the grain here and say that you can, in an albeit silly way, interpret

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as a ratio of real numbers.

为了给答案列表增加一些多样性,我打算反其道而行之,说一下你可以用一种虽然有些愚蠢的方式,将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 解释为实数的比率。

For every (differentiable) function

f

f

f, we can define a function

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) of two real variables

x

x

x and

d

x

dx

dx via

对于每个(可微)函数

f

f

f,我们可以通过以下方式定义一个关于两个实变量

x

x

x 和

d

x

dx

dx 的函数

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx):

d f ( x ; d x ) = f ′ ( x ) d x df(x; dx) = f'(x)dx df(x;dx)=f′(x)dx.

Here,

d

x

dx

dx is just a real number, and no more. (In particular, it is not a differential 1-form, nor an infinitesimal.) So, when

d

x

≠

0

dx \neq 0

dx=0, we can write:

这里,

d

x

dx

dx 仅仅是一个实数,别无其他。(特别是,它不是微分 1-形式,也不是无穷小量。)所以,当

d

x

≠

0

dx \neq 0

dx=0 时,我们可以写成:

d f ( x ; d x ) d x = f ′ ( x ) \frac{df(x; dx)}{dx} = f'(x) dxdf(x;dx)=f′(x).

All of this, however, should come with a few remarks.

然而,所有这些都需要附带一些说明。

It is clear that these notations above do not constitute a definition of the derivative of

f

f

f. Indeed, we needed to know what the derivative

f

′

f'

f′ meant before defining the function

d

f

df

df. So in some sense, it’s just a clever choice of notation.

显然,上述符号并不构成

f

f

f 的导数的定义。事实上,在定义函数

d

f

df

df 之前,我们需要知道导数

f

′

f'

f′ 的含义。所以在某种意义上,这只是一种巧妙的符号选择。

But if it’s just a trick of notation, why do I mention it at all? The reason is that in higher dimensions, the function

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) actually becomes the focus of study, in part because it contains information about all the partial derivatives.

但如果这只是符号上的技巧,我为什么还要提呢?原因是在更高维度中,函数

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) 实际上成为了研究的焦点,部分原因是它包含了所有偏导数的信息。

To be more concrete, for multivariable functions

f

:

R

n

→

R

f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}

f:Rn→R, we can define a function

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) of two

n

n

n-dimensional variables

x

,

d

x

∈

R

n

x, dx \in \mathbb{R}^n

x,dx∈Rn via

更具体地说,对于多元函数

f

:

R

n

→

R

f: \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R}

f:Rn→R,我们可以通过以下方式定义一个关于两个

n

n

n 维变量

x

,

d

x

∈

R

n

x, dx \in \mathbb{R}^n

x,dx∈Rn 的函数

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx):

d f ( x ; d x ) = d f ( x 1 , … , x n ; d x 1 , … , d x n ) = ∂ f ∂ x 1 d x 1 + … + ∂ f ∂ x n d x n df(x; dx) = df(x_1, \ldots, x_n; dx_1, \ldots, dx_n) = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1} dx_1 + \ldots + \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n} dx_n df(x;dx)=df(x1,…,xn;dx1,…,dxn)=∂x1∂fdx1+…+∂xn∂fdxn.

Notice that this map

d

f

df

df is linear in the variable

d

x

dx

dx. That is, we can write:

注意,映射

d

f

df

df 在变量

d

x

dx

dx 中是线性的。也就是说,我们可以写成:

d f ( x ; d x ) = ( ∂ f ∂ x 1 , … , ∂ f ∂ x n ) ( d x 1 ⋮ d x n ) = A ( d x ) df(x; dx) = \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}, \ldots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x_n} \right) \begin{pmatrix} dx_1 \\ \vdots \\ dx_n \end{pmatrix} = A(dx) df(x;dx)=(∂x1∂f,…,∂xn∂f) dx1⋮dxn =A(dx),

where

A

A

A is the

1

×

n

1 \times n

1×n row matrix of partial derivatives.

其中

A

A

A 是偏导数的

1

×

n

1 \times n

1×n 行矩阵。

In other words, the function

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) can be thought of as a linear function of

d

x

dx

dx, whose matrix has variable coefficients (depending on

x

x

x).

换句话说,函数

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) 可以被看作是

d

x

dx

dx 的线性函数,其矩阵具有可变系数(取决于

x

x

x)。

So for the 1-dimensional case, what is really going on is a trick of dimension. That is, we have the variable

1

×

1

1 \times 1

1×1 matrix

(

f

′

(

x

)

)

(f'(x))

(f′(x)) acting on the vector

d

x

∈

R

1

dx \in \mathbb{R}^1

dx∈R1 – and it just so happens that vectors in

R

1

\mathbb{R}^1

R1 can be identified with scalars, and so can be divided.

所以在一维情况下,真正发生的是维度上的技巧。也就是说,我们有可变的

1

×

1

1 \times 1

1×1 矩阵

(

f

′

(

x

)

)

(f'(x))

(f′(x)) 作用于向量

d

x

∈

R

1

dx \in \mathbb{R}^1

dx∈R1——而恰好

R

1

\mathbb{R}^1

R1 中的向量可以与标量等同,因此可以进行除法运算。

edited Feb 10, 2024 at 0:59

answered Feb 10, 2011 at 9:25

Jesse Madnick

Cotangent space. Also, in case of multiple variables if you fix

d

x

2

,

…

,

d

x

n

=

0

dx_2, \ldots, dx_n = 0

dx2,…,dxn=0 you can still divide by

d

x

1

dx_1

dx1 and get the derivative. And nothing stops you from defining differential first and then defining derivatives as its coefficients.

余切空间。此外,在多变量情况下,如果你固定

d

x

2

,

…

,

d

x

n

=

0

dx_2, \ldots, dx_n = 0

dx2,…,dxn=0,仍然可以除以

d

x

1

dx_1

dx1 得到导数。而且没有什么能阻止你先定义微分,然后将导数定义为其系数。

– Aleksei Averchenko

Commented Feb 11, 2011 at 2:30

Well, canonically differentials are members of contangent bundle, and

d

x

dx

dx is in this case its basis.

嗯,规范地说,微分是余切丛的元素,而在这种情况下

d

x

dx

dx 是它的基。

– Aleksei Averchenko

Commented Feb 11, 2011 at 5:54

Maybe I’m misunderstanding you, but I never made any reference to differentials in my post. My point is that

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) can be likened to the pushforward map

f

∗

f_*

f∗. Of course one can also make an analogy with the actual differential 1-form

d

f

df

df, but that’s something separate.

也许我误解了你,但我在帖子中从未提到过微分。我的观点是

d

f

(

x

;

d

x

)

df(x; dx)

df(x;dx) 可以比作前推映射

f

∗

f_*

f∗。当然,也可以与实际的微分 1-形式

d

f

df

df 进行类比,但那是另一回事。

– Jesse Madnick

Commented Feb 11, 2011 at 6:18

Sure the input is a vector, that’s why these linearizations are called covectors, which are members of cotangent space. I can’t see why you are bringing up pushforwards when there is a better description right there.

当然,输入是一个向量,这就是为什么这些线性化被称为余向量,它们是余切空间的元素。我不明白为什么在有更好的描述的情况下,你还要提前推映射。

– Aleksei Averchenko

Commented Feb 11, 2011 at 9:12

I just don’t think pushforward is the best way to view differential of a function with codomain

R

\mathbb{R}

R (although it is perfectly correct), it’s just a too complex idea that has more natural treatment.

我只是认为,前推映射不是看待余域为

R

\mathbb{R}

R 的函数的微分的最佳方式(尽管它是完全正确的),这只是一个过于复杂的概念,有更自然的处理方式。

– Aleksei Averchenko

Commented Feb 12, 2011 at 4:25

My favorite “counterexample” to the derivative acting like a ratio: the implicit differentiation formula for two variables. We have

我最喜欢的关于导数表现得不像比率的“反例”:两个变量的隐函数求导公式。我们有

d y d x = − ∂ F / ∂ x ∂ F / ∂ y \frac{dy}{dx} = -\frac{\partial F / \partial x}{\partial F / \partial y} dxdy=−∂F/∂y∂F/∂x

The formula is almost what you would expect, except for that pesky minus sign.

这个公式几乎和你预期的一样,除了那个讨厌的负号。

See Implicit differentiation for the rigorous definition of this formula.

参见隐函数求导以了解该公式的严格定义。

edited Dec 16, 2021 at 22:33

answered Nov 14, 2012 at 6:42

asmeurer

Yes, but their is a fake proof of this that comes from that kind a reasoning. If

f

(

x

,

y

)

f(x, y)

f(x,y) is a function of two variables, then

d

f

=

∂

f

∂

x

d

x

+

∂

f

∂

y

df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dx + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}

df=∂x∂fdx+∂y∂f. Now if we pick a level curve

f

(

x

,

y

)

=

0

f(x, y) = 0

f(x,y)=0, then

d

f

=

0

df = 0

df=0, so solving for

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy gives us the expression above.

是的,但有一种基于这种推理的伪证明。如果

f

(

x

,

y

)

f(x, y)

f(x,y) 是一个二元函数,那么

d

f

=

∂

f

∂

x

d

x

+

∂

f

∂

y

df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dx + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}

df=∂x∂fdx+∂y∂f。现在如果我们取一条等高曲线

f

(

x

,

y

)

=

0

f(x, y) = 0

f(x,y)=0,那么

d

f

=

0

df = 0

df=0,因此解出

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 就得到了上面的表达式。

– Baby Dragon

Commented Jun 16, 2013 at 19:03

Pardon me, but how is this a “fake proof”?

请原谅我,但这怎么是一个“伪证明”呢?

– Lurco

Commented Apr 28, 2014 at 0:04

@Lurco: He meant

d

f

=

∂

f

∂

x

d

x

+

∂

f

∂

y

d

y

df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dx + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} dy

df=∂x∂fdx+∂y∂fdy, where those ‘infinitesimals’ are not proper numbers and hence it is wrong to simply substitute

d

f

=

0

df = 0

df=0, because in fact if we are consistent in our interpretation

d

f

=

0

df = 0

df=0 would imply

d

x

=

d

y

=

0

dx = dy = 0

dx=dy=0 and hence we can’t get

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy anyway. But if we are inconsistent, we can ignore that and proceed to get the desired expression. Correct answer but fake proof.

@卢尔科:他的意思是

d

f

=

∂

f

∂

x

d

x

+

∂

f

∂

y

d

y

df = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} dx + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} dy

df=∂x∂fdx+∂y∂fdy,其中那些“无穷小量”不是真正的数,因此简单代入

d

f

=

0

df = 0

df=0 是错误的,因为事实上,如果我们的解释一致,

d

f

=

0

df = 0

df=0 会意味着

d

x

=

d

y

=

0

dx = dy = 0

dx=dy=0,因此无论如何都无法得到

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy。但如果我们不一致,就可以忽略这一点,进而得到想要的表达式。答案是正确的,但证明是伪的。

– user21820

Commented May 13, 2014 at 9:58

I agree that this is a good example to show why such notation is not so simple as one might think, but in this case I could say that

d

x

dx

dx is not the same as

∂

x

\partial x

∂x. Do you have an example where the terms really cancel to give the wrong answer?

我同意这是一个很好的例子,说明了为什么这样的符号并不像人们想象的那么简单,但在这种情况下,我可以说

d

x

dx

dx 和

∂

x

\partial x

∂x 不一样。你有例子说明这些项真的会相互抵消而得到错误的答案吗?

– user21820

Commented May 13, 2014 at 10:07

-1 I’m sorry, but this is based on a misapprehension. The

d

y

/

d

x

dy/dx

dy/dx is for the the goemetric entities which are the level curves, the partial derivatives are for the function we are taking level curves from. This doesn’t demonstrate what it is claimed to as we are using a different entity on the left than on the right.

-1 抱歉,但这是基于一种误解。

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是针对等高曲线这一几何实体的,偏导数是针对我们从中取等高曲线的函数的。这并不能证明所声称的内容,因为我们在左边和右边使用的是不同的实体。

– John Robertson

Commented May 18, 2015 at 4:25

It is best to think of

d

d

x

\frac{d}{dx}

dxd as an operator which takes the derivative, with respect to

x

x

x, of whatever expression follows.

最好把

d

d

x

\frac{d}{dx}

dxd 看作一个算子,它对后面的任何表达式求关于

x

x

x 的导数。

edited Dec 15, 2014 at 15:53

answered Feb 9, 2011 at 23:42

Tobin Fricke

This is an opinion offered without any justification.

这是一个没有任何依据的观点。

– user13618

Commented Apr 30, 2014 at 5:20

What kind of justification do you want? It is a very good argument for telling that

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is not a fraction! This tells us that

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy needs to be seen as

d

d

x

(

y

)

\frac{d}{dx}(y)

dxd(y) where

d

d

x

\frac{d}{dx}

dxd is an opeartor.

你想要什么样的依据呢?这是说明

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 不是分数的一个很好的论据!这告诉我们,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 需要被看作

d

d

x

(

y

)

\frac{d}{dx}(y)

dxd(y),其中

d

d

x

\frac{d}{dx}

dxd 是一个算子。

– Emo

Commented May 2, 2014 at 20:43

Over the hyperreals,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is a ratio and one can view

d

d

x

\frac{d}{dx}

dxd as an operator. Therefore Tobin’s reply is not a good argument for “telling that dy/dx is not a fraction”.

在超实数上,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是一个比率,并且可以把

d

d

x

\frac{d}{dx}

dxd 看作一个算子。因此,托宾的回答并不是“说明

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 不是分数”的好论据。

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Dec 15, 2014 at 16:11

This doesn’t address the question.

y

x

\frac{y}{x}

xy is clearly a ratio, but it can be also thought as the operator

1

x

\frac{1}{x}

x1 acting on

y

y

y by multiplication, so “operator” and “ratio” are not exclusive.

这并没有解决问题。

y

x

\frac{y}{x}

xy 显然是一个比率,但它也可以被看作算子

1

x

\frac{1}{x}

x1 通过乘法作用于

y

y

y,所以“算子”和“比率”并不是互斥的。

– mlainz

Commented Jan 29, 2019 at 10:52

Thanks for the comments - I think all of these criticisms of my answer are valid.

感谢这些评论——我认为对我的回答的所有这些批评都是有道理的。

– Tobin Fricke

Commented Jan 30, 2019 at 19:38

In Leibniz’s mathematics, if

y

=

x

2

y = x^2

y=x2 then

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy would be “equal” to

2

x

2x

2x, but the meaning of “equality” to Leibniz was not the same as it is to us. He emphasized repeatedly (for example in his 1695 response to Nieuwentijt) that he was working with a generalized notion of equality “up to” a negligible term. Also, Leibniz used several different pieces of notation for “equality”. One of them was the symbol “⌜⌝”. To emphasize the point, one could write

在莱布尼茨的数学中,如果

y

=

x

2

y = x^2

y=x2,那么

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 会“等于”

2

x

2x

2x,但对莱布尼茨来说,“等于”的含义和我们现在所理解的并不相同。他反复强调(例如在 1695 年对纽文泰特的回应中),他所使用的是一种“直至”可忽略项的广义相等概念。此外,莱布尼茨为“相等”使用了几种不同的符号。其中一个是“⌜⌝”。为了强调这一点,可以写成

y = x 2 → d y d x ⌜ ⌝ 2 x y = x^2 \to \frac{dy}{dx} ⌜⌝ 2x y=x2→dxdy┌┐2x

where

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is literally a ratio. When one expresses Leibniz’s insight in this fashion, one is less tempted to commit an ahistorical error of accusing him of having committed a logical inaccuracy.

其中

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 确实是一个比率。当人们以这种方式表达莱布尼茨的见解时,就不太可能犯一种非历史的错误,即指责他存在逻辑上的不准确。

In more detail,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is a true ratio in the following sense. We choose an infinitesimal

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx, and consider the corresponding

y

y

y-increment

Δ

y

=

f

(

x

+

Δ

x

)

−

f

(

x

)

\Delta y = f(x + \Delta x) - f(x)

Δy=f(x+Δx)−f(x). The ratio

Δ

y

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy is then infinitely close to the derivative

f

′

(

x

)

f'(x)

f′(x). We then set

d

x

=

Δ

x

dx = \Delta x

dx=Δx and

d

y

=

f

′

(

x

)

d

x

dy = f'(x)dx

dy=f′(x)dx so that

f

′

(

x

)

=

d

y

d

x

f'(x) = \frac{dy}{dx}

f′(x)=dxdy by definition. One of the advantages of this approach is that one obtains an elegant proof of chain rule

d

y

d

x

=

d

y

d

u

d

u

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{dy}{du} \frac{du}{dx}

dxdy=dudydxdu by applying the standard part function to the equality

Δ

y

Δ

x

=

Δ

y

Δ

u

Δ

u

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta u} \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy=ΔuΔyΔxΔu.

更详细地说,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 在以下意义上是一个真正的比率。我们选择一个无穷小量

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx,并考虑相应的

y

y

y 的增量

Δ

y

=

f

(

x

+

Δ

x

)

−

f

(

x

)

\Delta y = f(x + \Delta x) - f(x)

Δy=f(x+Δx)−f(x)。那么比率

Δ

y

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy 与导数

f

′

(

x

)

f'(x)

f′(x) 无限接近。然后我们令

d

x

=

Δ

x

dx = \Delta x

dx=Δx 且

d

y

=

f

′

(

x

)

d

x

dy = f'(x)dx

dy=f′(x)dx,这样根据定义就有

f

′

(

x

)

=

d

y

d

x

f'(x) = \frac{dy}{dx}

f′(x)=dxdy。这种方法的一个优点是,通过对等式

Δ

y

Δ

x

=

Δ

y

Δ

u

Δ

u

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} = \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta u} \frac{\Delta u}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy=ΔuΔyΔxΔu 应用标准部分函数,可以得到链式法则

d

y

d

x

=

d

y

d

u

d

u

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{dy}{du} \frac{du}{dx}

dxdy=dudydxdu 的简洁证明。

In the real-based approach to the calculus, there are no infinitesimals and therefore it is impossible to interpret

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as a true ratio. Therefore claims to that effect have to be relativized modulo anti-infinitesimal foundational commitments.

在基于实数的微积分方法中,不存在无穷小量,因此不可能将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 解释为真正的比率。因此,有关这方面的主张必须相对于反无穷小的基础承诺来进行调整。

Note 1. I recently noticed that Leibniz’s ⌜⌝ notation occurs several times in Margaret Baron’s book The origins of infinitesimal calculus, starting on page 282. It’s well worth a look.

注 1. 我最近注意到,玛格丽特·巴伦的《无穷小 Calculus 的起源》一书从第 282 页开始多次出现莱布尼茨的“⌜⌝”符号。这本书很值得一读。

Note 2. It should be clear that Leibniz did view

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as a ratio. (Some of the other answers seem to be worded ambiguously with regard to this point.)

注 2. 显然,莱布尼茨确实将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 视为一个比率。(其他一些答案在这一点上的表述似乎模棱两可。)

edited May 29, 2016 at 6:53

answered Aug 12, 2013 at 19:31

Mikhail Katz

This is somewhat beside the point, but I don’t think that applying the standard part function to prove the Chain Rule is particularly more (or less) elegant than applying the limit as

Δ

x

→

0

\Delta x \to 0

Δx→0. Both attempts hit a snag since

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu might be

0

0

0 when

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx is not (regardless of whether one is thinking of

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx as an infinitesimal quantity or as a standard variable approaching

0

0

0), as for example when

u

=

x

sin

(

1

/

x

)

u = x \sin(1/x)

u=xsin(1/x).

这有点离题,但我不认为应用标准部分函数来证明链式法则比应用

Δ

x

→

0

\Delta x \to 0

Δx→0 的极限更(或更不)简洁。两种尝试都会遇到一个障碍,因为当

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx 不为零时,

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu 可能为零(无论人们将

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx 视为无穷小量还是趋近于 0 的标准变量),例如当

u

=

x

sin

(

1

/

x

)

u = x \sin(1/x)

u=xsin(1/x) 时。

– Toby Bartels

Commented Feb 21, 2018 at 23:26

This snag does exist in the epsilon-delta setting, but it does not exist in the infinitesimal setting because if the derivative is nonzero then one necessarily has

Δ

u

≠

0

\Delta u \neq 0

Δu=0, and if the derivative is zero then there is nothing to prove. @TobyBartels

这个障碍在 ε-δ 设定中确实存在,但在无穷小设定中不存在,因为如果导数非零,那么必然有

Δ

u

≠

0

\Delta u \neq 0

Δu=0;如果导数为零,那么就没有什么可证明的了。@托比·巴特尔斯

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Feb 22, 2018 at 9:47

Notice that the function you mentioned is undefined (or not differentiable if you define it) at zero, so chain rule does not apply in this case anyway. @TobyBartels

请注意,你提到的函数在零点是未定义的(或者如果定义了的话是不可微的),所以链式法则在这种情况下无论如何都不适用。@托比·巴特尔斯

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Feb 22, 2018 at 10:15

Sorry, that should be

u

=

x

2

sin

(

1

/

x

)

u = x^2 \sin(1/x)

u=x2sin(1/x) (extended by continuity to

x

=

0

x = 0

x=0, which is the argument at issue). If the infinitesimal

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx is

1

/

(

n

π

)

1/(n\pi)

1/(nπ) for some (necessarily infinite) hyperinteger

n

n

n, then

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu is

0

0

0. It’s true that in this case, the derivative

d

u

/

d

x

du/dx

du/dx is

0

0

0 too, but I don’t see why that matters; why is there nothing to prove in that case? (Conversely, if there’s nothing to prove in that case, then doesn’t that save the epsilontic proof as well? That’s the only way that

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu can be

0

0

0 arbitrarily close to the argument.)

抱歉,应该是

u

=

x

2

sin

(

1

/

x

)

u = x^2 \sin(1/x)

u=x2sin(1/x)(通过连续性延拓到

x

=

0

x = 0

x=0,这正是有争议的论点)。如果无穷小量

Δ

x

\Delta x

Δx 是某个(必然是无穷的)超整数

n

n

n 的

1

/

(

n

π

)

1/(n\pi)

1/(nπ),那么

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu 就是 0。诚然,在这种情况下,导数

d

u

/

d

x

du/dx

du/dx 也是 0,但我不明白这为什么重要;为什么在这种情况下没有什么可证明的呢?(相反,如果在这种情况下没有什么可证明的,那么这难道不也拯救了 ε-δ 证明吗?这是

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu 能在接近论点处任意为 0 的唯一方式。)

– Toby Bartels

Commented Feb 23, 2018 at 12:21

If

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu is zero then obviously

Δ

y

\Delta y

Δy is also zero and therefore both sides of the formula for chain rule are zero. On the other hand, if the derivative of

u

=

g

(

x

)

u = g(x)

u=g(x) is nonzero then

Δ

u

≠

0

\Delta u \neq 0

Δu=0. This is not necessarily the case when one works with finite differences. @TobyBartels

如果

Δ

u

\Delta u

Δu 为零,那么显然

Δ

y

\Delta y

Δy 也为零,因此链式法则公式的两边都是零。另一方面,如果

u

=

g

(

x

)

u = g(x)

u=g(x) 的导数非零,那么

Δ

u

≠

0

\Delta u \neq 0

Δu=0。当使用有限差分法时,情况不一定如此。@托比·巴特尔斯

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Feb 24, 2018 at 19:28

Typically, the

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy notation is used to denote the derivative, which is defined as the limit we all know and love (see Arturo Magidin’s answer). However, when working with differentials, one can interpret

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as a genuine ratio of two fixed quantities.

通常,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 符号用于表示导数,其定义是我们都熟知且认可的极限(见阿图罗·马吉丁的回答)。然而,在处理微分时,可以将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 解释为两个固定量的真正比率。

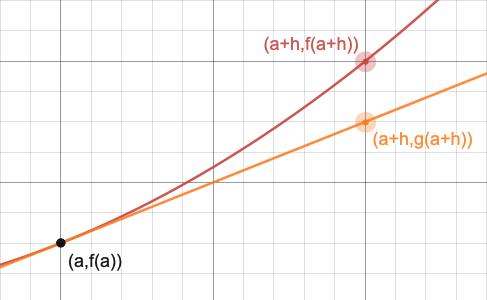

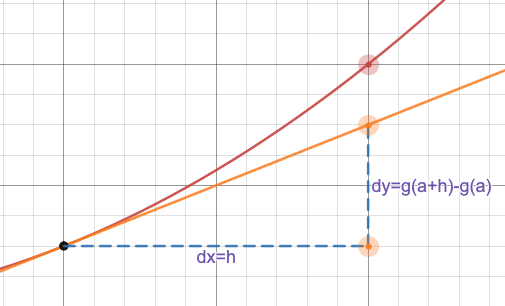

Draw a graph of some smooth function

f

f

f and its tangent line at

x

=

a

x = a

x=a. Starting from the point

(

a

,

f

(

a

)

)

(a, f(a))

(a,f(a)), move

d

x

dx

dx units right along the tangent line (not along the graph of

f

f

f). Let

d

y

dy

dy be the corresponding change in

y

y

y.

画出某个光滑函数

f

f

f 的图像及其在

x

=

a

x = a

x=a 处的切线。从点

(

a

,

f

(

a

)

)

(a, f(a))

(a,f(a)) 开始,沿着切线(不是沿着

f

f

f 的图像)向右移动

d

x

dx

dx 个单位。令

d

y

dy

dy 为相应的

y

y

y 的变化量。

So, we moved

d

x

dx

dx units right,

d

y

dy

dy units up, and stayed on the tangent line. Therefore the slope of the tangent line is exactly

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy. However, the slope of the tangent at

x

=

a

x = a

x=a is also given by

f

′

(

a

)

f'(a)

f′(a), hence the equation

这样,我们向右移动了

d

x

dx

dx 个单位,向上移动了

d

y

dy

dy 个单位,并且始终在切线上。因此,切线的斜率正好是

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy。然而,在

x

=

a

x = a

x=a 处的切线斜率也由

f

′

(

a

)

f'(a)

f′(a) 给出,因此有方程

d y d x = f ′ ( a ) \frac{dy}{dx} = f'(a) dxdy=f′(a)

holds when

d

y

dy

dy and

d

x

dx

dx are interpreted as fixed, finite changes in the two variables

x

x

x and

y

y

y. In this context, we are not taking a limit on the left hand side of this equation, and

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is a genuine ratio of two fixed quantities. This is why we can then write

d

y

=

f

′

(

a

)

d

x

dy = f'(a)dx

dy=f′(a)dx.

当

d

y

dy

dy 和

d

x

dx

dx 被解释为两个变量

x

x

x 和

y

y

y 的固定、有限变化时,该式成立。在这种情况下,我们没有对等式左边取极限,且

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是两个固定量的真正比率。这就是为什么我们可以写成

d

y

=

f

′

(

a

)

d

x

dy = f'(a)dx

dy=f′(a)dx。

edited Mar 14, 2013 at 3:35

answered Nov 5, 2011 at 16:31

Brendan Cordy

This sounds a lot like the explanation of differentials that I recall hearing from my Calculus I instructor (an analyst of note, an expert on Wiener integrals): “

d

y

dy

dy and

d

x

dx

dx are any two numbers whose ratio is the derivative . . . they are useful for people who are interested in (sniff) approximations.”

这听起来很像我记得的微积分 I 老师(一位著名的分析师,维纳积分专家)对比分的解释:“

d

y

dy

dy 和

d

x

dx

dx 是任何两个比率为导数的数……它们对那些对(哼)近似感兴趣的人很有用。”

– bof

Commented Dec 28, 2013 at 3:34

@bof: But we can’t describe almost every real number in the real world, so I guess having approximations is quite good. =)

@博夫:但在现实世界中,我们几乎无法描述每一个实数,所以我想有近似值已经相当不错了。=)

– user21820

Commented May 13, 2014 at 10:13

@user21820 anything that we can approximate to arbitrary precision we can define… It’s the result of that algorithm.

@用户 21820 任何我们可以近似到任意精度的东西,我们都可以定义……这是那个算法的结果。

– k_g

Commented May 18, 2015 at 1:34

@k_g: Yes of course. My comment was last year so I don’t remember what I meant at that time anymore, but I probably was trying to say that since we already are limited to countably many definable reals, it’s much worse if we limit ourselves even further to closed forms of some kind and eschew approximations. Even more so, in the real world we rarely have exact values but just confidence intervals anyway, and so approximations are sufficient for almost all practical purposes.

@凯·吉:当然。我的评论是去年的,所以我已经不记得当时的意思了,但我可能是想说,由于我们已经局限于可数多个可定义的实数,如果我们进一步将自己局限于某种闭形式而避开近似,情况会更糟。更重要的是,在现实世界中,我们很少有精确值,而只有置信区间,因此近似值对于几乎所有实际用途来说已经足够了。

– user21820

Commented May 18, 2015 at 5:04

- This is very close to the way Vladimir Arnol’d explains why the derivative is really a ratio of real numbers in his work on Ordinary Differential Equations.

- 这与弗拉基米尔·阿诺尔德在其常微分方程著作中解释为什么导数确实是实数的比率的方式非常接近。

– Francis Davey

Commented Apr 6, 2024 at 4:28

Of course it is a ratio.

当然它是一个比率。

d

y

dy

dy and

d

x

dx

dx are differentials. Thus they act on tangent vectors, not on points. That is, they are functions on the tangent manifold that are linear on each fiber. On the tangent manifold the ratio of the two differentials

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is just a ratio of two functions and is constant on every fiber (except being ill defined on the zero section) Therefore it descends to a well defined function on the base manifold. We refer to that function as the derivative.

d

y

dy

dy 和

d

x

dx

dx 是微分。因此,它们作用于切向量,而不是点。也就是说,它们是切流形上的函数,在每个纤维上都是线性的。在切流形上,两个微分的比率

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 只是两个函数的比率,并且在每个纤维上都是常数(除了在零截面上定义不明确)。因此,它可以导出底流形上的一个明确定义的函数。我们将这个函数称为导数。

As pointed out in the original question many calculus one books these days even try to define differentials loosely and at least informally point out that for differentials

d

y

=

f

′

(

x

)

d

x

dy = f'(x)dx

dy=f′(x)dx (Note that both sides of this equation act on vectors, not on points). Both

d

y

dy

dy and

d

x

dx

dx are perfectly well defined functions on vectors and their ratio is therefore a perfectly meaningful function on vectors. Since it is constant on fibers (minus the zero section), then that well defined ratio descends to a function on the original space.

正如原始问题中所指出的,如今许多微积分入门书籍甚至试图宽松地定义微分,并且至少非正式地指出,对于微分有

d

y

=

f

′

(

x

)

d

x

dy = f'(x)dx

dy=f′(x)dx(注意,该方程的两边都作用于向量,而不是点)。

d

y

dy

dy 和

d

x

dx

dx 都是向量上定义完善的函数,因此它们的比率是向量上一个非常有意义的函数。由于它在纤维上是常数(减去零截面),所以这个定义完善的比率可以导出原始空间上的一个函数。

At worst one could object that the ratio

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is not defined on the zero section.

最坏的情况下,有人可能会反对说比率

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 在零截面上没有定义。

edited Jan 29, 2017 at 3:18

answered Apr 30, 2014 at 5:16

John Robertson

Can anything meaningful be made of higher order derivatives in the same way?

能用同样的方式理解高阶导数的意义吗?

– Francis Davey

Commented Mar 8, 2015 at 10:41

You can simply mimic the procedure to get a second or third derivative. As I recall when I worked that out the same higher partial derivatives get realized in it multiple ways which is awkward. The standard approach is more direct. It is called Jets and there is currently a Wikipedia article on Jet (mathematics).

你可以简单地模仿这个过程来得到二阶或三阶导数。我记得当我推导出时,同样的高阶偏导数会以多种方式出现,这很麻烦。标准方法更直接。这被称为射流(Jets),目前维基百科上有一篇关于射流(数学)的文章。

– John Robertson

Commented May 2, 2015 at 16:51

Tangent manifold is the tangent bundle. And what it means is that

d

y

dy

dy and

d

x

dx

dx are both perfectly well defined functions on the tangent manifold, so we can divide one by the other giving

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy. It turns out that the value of

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy on a given tangent vector only depends on the base point of that vector. As its value only depends on the base point, we can take

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as really defining a function on original space. By way of analogy, if

f

(

u

,

v

)

=

3

u

+

sin

(

u

)

+

7

f(u, v) = 3u + \sin(u) + 7

f(u,v)=3u+sin(u)+7 then even though

f

f

f is a function of both

u

u

u and

v

v

v, since

v

v

v doesn’t affect the output, we can also consider

f

f

f to be a function of

u

u

u alone.

切流形就是切丛。这意味着

d

y

dy

dy 和

d

x

dx

dx 都是切流形上定义完善的函数,所以我们可以将一个除以另一个得到

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy。事实证明,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 在给定切向量上的值只取决于该向量的基点。由于它的值只取决于基点,我们可以将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 视为在原始空间上真正定义了一个函数。打个比方,如果

f

(

u

,

v

)

=

3

u

+

sin

(

u

)

+

7

f(u, v) = 3u + \sin(u) + 7

f(u,v)=3u+sin(u)+7,那么尽管

f

f

f 是

u

u

u 和

v

v

v 的函数,但由于

v

v

v 不影响输出,我们也可以认为

f

f

f 只是

u

u

u 的函数。

– John Robertson

Commented Jul 6, 2015 at 15:53

Your answer is in the opposition with many other answers here! 😃 I am confused! So is it a ratio or not or both!?

你的回答与这里的许多其他回答相悖!😃 我很困惑!那么它到底是不是比率,还是两者都是呢?

– Hosein Rahnama

Commented Jul 15, 2016 at 20:24

How do you simplify all this to the more special-case level of basic calculus where all spaces are Euclidean? The invocations of manifold theory suggest this is an approach that is designed for non-Euclidean geometries.

你如何将所有这些简化到所有空间都是欧几里得空间的基础微积分的更特殊情况层面?对微分流形理论的引用表明,这是一种为非欧几里得几何设计的方法。

– The_Sympathizer

Commented Feb 3, 2017 at 7:19

The notation

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy - in elementary calculus - is simply that: notation to denote the derivative of, in this case,

y

y

y w.r.t.

x

x

x. (In this case

f

′

(

x

)

f'(x)

f′(x) is another notation to express essentially the same thing, i.e.

d

f

(

x

)

d

x

\frac{df(x)}{dx}

dxdf(x) where

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) signifies the function

f

f

f w.r.t. the dependent variable

x

x

x. According to what you’ve written above,

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) is the function which takes values in the target space

y

y

y).

符号

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 在初等微积分中仅仅是:表示在这种情况下

y

y

y 对

x

x

x 的导数的符号。(在这种情况下,

f

′

(

x

)

f'(x)

f′(x) 是另一种表示本质上相同事物的符号,即

d

f

(

x

)

d

x

\frac{df(x)}{dx}

dxdf(x),其中

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) 表示关于因变量

x

x

x 的函数

f

f

f。根据你上面写的内容,

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) 是在目标空间

y

y

y 中取值的函数。)

Furthermore, by definition,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy at a specific point

x

0

x_0

x0 within the domain

x

x

x is the real number

L

L

L, if it exists. Otherwise, if no such number exists, then the function

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) does not have a derivative at the point in question, (i.e. in our case

x

0

x_0

x0).

此外,根据定义,在定义域

x

x

x 内的特定点

x

0

x_0

x0 处,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是实数

L

L

L(如果它存在)。否则,如果不存在这样的数,那么函数

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) 在该点(即在我们的例子中

x

0

x_0

x0)处没有导数。

For further information you can read the Wikipedia article: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derivative

欲了解更多信息,你可以阅读维基百科文章:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Derivative

answered Feb 9, 2011 at 17:00

Anonymous

So glad that wikipedia finally added an entry for the derivative…

真高兴维基百科终于添加了关于导数的条目……

– The Chaz 2.0

Commented Aug 10, 2011 at 17:50

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is definitely not a ratio - it is the limit (if it exists) of a ratio. This is Leibniz’s notation of the derivative (c. 1670) which prevailed to the one of Newton

y

˙

(

x

)

\dot{y}(x)

y˙(x).

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 绝对不是一个比率——它是一个比率的极限(如果存在的话)。这是莱布尼茨的导数符号(约 1670 年),它取代了牛顿的

y

˙

(

x

)

\dot{y}(x)

y˙(x) 符号。

Still, most Engineers and even many Applied Mathematicians treat it as a ratio. A very common such case is when solving separable ODEs, i.e. equations of the form

尽管如此,大多数工程师甚至许多应用数学家都将其视为比率。一个非常常见的情况是在求解可分离变量的常微分方程时,即形如

d y d x = f ( x ) g ( y ) \frac{dy}{dx} = f(x)g(y) dxdy=f(x)g(y),

writing the above as

将上式写成

f ( x ) d x = d y g ( y ) f(x)dx = \frac{dy}{g(y)} f(x)dx=g(y)dy,

and then integrating.

然后进行积分。

Apparently this is not Mathematics, it is a symbolic calculus.

显然这不是数学,而是符号演算。

Why are we allowed to integrate the left hand side with respect to

x

x

x and the right hand side with respect to

y

y

y? What is the meaning of that?

为什么我们可以对左边关于

x

x

x 积分,对右边关于

y

y

y 积分?这有什么意义呢?

This procedure often leads to the right solution, but not always. For example applying this method to the IVP

这个过程通常会得到正确的解,但并非总是如此。例如,将这种方法应用于初值问题

KaTeX parse error: Unexpected end of input in a macro argument, expected '}' at end of input: …(0) = -1, \tag{\starKaTeX parse error: Expected 'EOF', got '}' at position 1: }̲

we get, for some constant

c

c

c,

我们得到,对于某个常数

c

c

c,

ln ( y + 1 ) = ∫ d y y + 1 = ∫ d x = x + c \ln(y + 1) = \int \frac{dy}{y + 1} = \int dx = x + c ln(y+1)=∫y+1dy=∫dx=x+c,

equivalently

等价地

y ( x ) = e x + c − 1 y(x) = e^{x + c} - 1 y(x)=ex+c−1.

Note that it is impossible to incorporate the initial condition

y

(

0

)

=

−

1

y(0) = -1

y(0)=−1, as

e

x

+

c

e^{x + c}

ex+c never vanishes. By the way, the solution of (

⋆

\star

⋆) is

y

(

x

)

≡

−

1

y(x) \equiv -1

y(x)≡−1.

注意,无法纳入初始条件

y

(

0

)

=

−

1

y(0) = -1

y(0)=−1,因为

e

x

+

c

e^{x + c}

ex+c 永远不会为零。顺便说一下,(

⋆

\star

⋆)的解是

y

(

x

)

≡

−

1

y(x) \equiv -1

y(x)≡−1。

Even worse, consider the case of the IVP

更糟糕的是,考虑初值问题

y ′ = 3 y 1 / 3 2 , y ( 0 ) = 0. ( ⋆ ⋆ ) y' = \frac{3y^{1/3}}{2}, \quad y(0) = 0. \tag{$\star\star$} y′=23y1/3,y(0)=0.(⋆⋆)

This IVP does not enjoy uniqueness. It possesses infinitely many solutions. Nevertheless, using this symbolic calculus, we obtain that

y

2

/

3

=

x

y^{2/3} = x

y2/3=x, which is one of the infinitely many solutions of (

⋆

⋆

\star\star

⋆⋆). Another one is

y

≡

0

y \equiv 0

y≡0.

这个初值问题不具有唯一性。它有无穷多个解。然而,使用这种符号演算,我们得到

y

2

/

3

=

x

y^{2/3} = x

y2/3=x,这是(

⋆

⋆

\star\star

⋆⋆)的无穷多个解之一。另一个解是

y

≡

0

y \equiv 0

y≡0。

In my opinion, Calculus should be taught rigorously, with

δ

\delta

δ’s and

ϵ

\epsilon

ϵ’s. Once these are well understood, then one can use such symbolic calculus, provided that he/she is convinced under which restrictions it is indeed permitted.

在我看来,微积分应该用

δ

\delta

δ 和

ϵ

\epsilon

ϵ 严格地教授。一旦这些被充分理解,那么人们就可以使用这种符号演算,前提是他/她确信在哪些限制条件下它确实是被允许的。

edited Aug 13, 2021 at 7:20

answered Dec 20, 2013 at 10:56

Yiorgos S. Smyrlis

I would disagree with this to some extent with your example as many would write the solution as

y

(

x

)

=

e

x

+

c

→

y

(

x

)

=

e

C

e

x

→

y

(

x

)

=

C

e

x

y(x) = e^{x + c} \to y(x) = e^C e^x \to y(x) = C e^x

y(x)=ex+c→y(x)=eCex→y(x)=Cex for the ‘appropriate’

C

C

C. Then we have

y

(

0

)

=

C

e

−

1

=

−

1

y(0) = C e - 1 = -1

y(0)=Ce−1=−1

在某种程度上,我不同意你的例子,因为许多人会将解写成

y

(

x

)

=

e

x

+

c

→

y

(

x

)

=

e

C

e

x

→

y

(

x

)

=

C

e

x

y(x) = e^{x + c} \to y(x) = e^C e^x \to y(x) = C e^x

y(x)=ex+c→y(x)=eCex→y(x)=Cex,其中

C

C

C 是“适当的”常数。

implying

C

=

0

C = 0

C=0 avoiding the issue which is how many introductory D.E. students would answer the question so the issue is never noticed.

这意味着

C

=

0

C = 0

C=0,从而回避了问题,而这正是许多微分方程入门学生回答这个问题的方式,所以这个问题从未被注意到。

– mathematics2x2life

Commented Dec 20, 2013 at 21:11

Your example works if

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is handled naively as a quotient. Given

d

y

d

x

=

y

+

1

\frac{dy}{dx} = y + 1

dxdy=y+1, we can deduce

d

x

=

d

y

y

+

1

dx = \frac{dy}{y + 1}

dx=y+1dy, but as even undergraduates know, you can’t divide by zero, so this is true only as long as

y

+

1

≠

0

y + 1 \neq 0

y+1=0. Thus we correctly conclude that (

⋆

\star

⋆) has no solution such that

y

+

1

≠

0

y + 1 \neq 0

y+1=0. Solving for

y

+

1

=

0

y + 1 = 0

y+1=0, we have

d

y

d

x

=

0

\frac{dy}{dx} = 0

dxdy=0, so

y

=

∫

0

d

x

=

0

+

C

y = \int 0 dx = 0 + C

y=∫0dx=0+C, and

y

(

0

)

=

−

1

y(0) = -1

y(0)=−1 constraints

C

=

−

1

C = -1

C=−1.

如果把

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 天真地当作商来处理,你的例子是成立的。已知

d

y

d

x

=

y

+

1

\frac{dy}{dx} = y + 1

dxdy=y+1,我们可以推出

d

x

=

d

y

y

+

1

dx = \frac{dy}{y + 1}

dx=y+1dy,但即使是本科生也知道,不能除以零,所以这只有在

y

+

1

≠

0

y + 1 \neq 0

y+1=0 时才成立。因此,我们正确地得出结论:(

⋆

\star

⋆)没有满足

y

+

1

≠

0

y + 1 \neq 0

y+1=0 的解。求解

y

+

1

=

0

y + 1 = 0

y+1=0,我们有

d

y

d

x

=

0

\frac{dy}{dx} = 0

dxdy=0,所以

y

=

∫

0

d

x

=

0

+

C

y = \int 0 dx = 0 + C

y=∫0dx=0+C,而

y

(

0

)

=

−

1

y(0) = -1

y(0)=−1 限制了

C

=

−

1

C = -1

C=−1。

– Gilles ‘SO- stop being evil’

Commented Aug 28, 2014 at 14:47

Since you mention Leibniz, it may be helpful to clarify that Leibniz did view

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as a ratio, for the sake of historical accuracy.

为了历史的准确性,既然你提到了莱布尼茨,或许有必要澄清一下,莱布尼茨确实将

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 视为一个比率。

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Dec 7, 2015 at 18:59

+1 for the interesting IVP example, I have never noticed that subtlety.

+1 为这个有趣的初值问题例子,我从未注意到这个微妙之处。

– electronpusher

Commented Apr 22, 2017 at 3:04

You got the wrong answer because you divided by zero, not because there’s anything wrong with treating the derivative as a ratio.

你得到错误的答案是因为你除以了零,而不是因为把导数当作比率来处理有什么问题。

– Toby Bartels

Commented Apr 29, 2017 at 4:20

It is not a ratio, just as

d

x

dx

dx is not a product.

它不是一个比率,就像

d

x

dx

dx 不是一个乘积一样。

answered Feb 9, 2011 at 17:06

Mariano Suárez-Álvarez

I wonder what motivated the downvote. I do find strange that students tend to confuse Leibniz’s notation with a quotient, and not

d

x

dx

dx (or even

log

\log

log!) with a product: they are both indivisible notations… My answer above just makes this point.

我想知道是什么导致了反对票。我确实觉得奇怪的是,学生们倾向于把莱布尼茨的符号与商混淆,而不会把

d

x

dx

dx(甚至

log

\log

log!)与乘积混淆:它们都是不可分割的符号……我上面的回答只是说明了这一点。

– Mariano Suárez-Álvarez

Commented Feb 10, 2011 at 0:12

I think that the reason why this confusion arises in some students may be related to the way in which this notation is used for instance when calculating integrals. Even though as you say, they are indivisible, they are separated “formally” in any calculus course in order to aid in the computation of integrals. I suppose that if the letters in

log

\log

log where separated in a similar way, the students would probably make the same mistake of assuming it is a product.

我认为一些学生产生这种困惑的原因可能与例如在计算积分时使用这种符号的方式有关。尽管如你所说,它们是不可分割的,但在任何微积分课程中,为了有助于积分的计算,它们会被“形式上”分开。我想,如果

log

\log

log 中的字母以类似的方式被分开,学生们可能也会犯同样的错误,认为它是一个乘积。

– Adrián Barquero

Commented Feb 10, 2011 at 4:09

I once heard a story of a university applicant, who was asked at interview to find

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy, didn’t understand the question, no matter how the interviewer phrased it. It was only after the interview wrote it out that the student promptly informed the interviewer that the two

d

d

d’s cancelled and he was in fact mistaken.

我曾经听说过一个关于大学申请者的故事,在面试中被要求求

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy,无论面试官怎么表述,他都不理解这个问题。直到面试官把它写出来,这个学生才立即告诉面试官,两个

d

d

d 可以抵消,实际上面试官是错的。

– jClark94

Commented Jan 30, 2012 at 19:54

Is this an answer??? Or just an imposition?

这是一个答案吗???还是仅仅是一种强加的观点?

– André Caldas

Commented Sep 12, 2013 at 13:12

I find the statement that “students tend to confuse Leibniz’s notation with a quotient” a bit problematic. The reason for this is that Leibniz certainly thought of

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy as a quotient. Since it behaves as a ratio in many contexts (such as the chain rule), it may be more helpful to the student to point out that in fact the derivative can be said to be “equal” to the ratio

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy if “equality” is interpreted as a more general relation of equality “up to an infinitesimal term”, which is how Leibniz thought of it. I don’t think this is comparable to thinking of “dx” as a product

我觉得“学生们倾向于把莱布尼茨的符号与商混淆”这种说法有点问题。原因是莱布尼茨肯定认为

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是一个商。由于它在许多情况下表现得像一个比率(如链式法则),向学生指出,如果“相等”被解释为一种更一般的“直至无穷小项”的相等关系(这正是莱布尼茨的想法),那么实际上导数可以说是“等于”比率

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy,这可能对学生更有帮助。我认为这与把“dx”看作乘积是不可比的。

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Oct 2, 2013 at 12:57

In most formulations,

d

x

d

y

\frac{dx}{dy}

dydx can not be interpreted as a ratio, as

d

x

dx

dx and

d

y

dy

dy do not actually exist in them. An exception to this is shown in this book. How it works, as Arturo said, is we allow infinitesimals (by using the hyperreal number system). It is well formulated, and I prefer it to limit notions, as this is how it was invented. Its just that they weren’t able to formulate it correctly back then. I will give a slightly simplified example. Let us say you are differentiating

y

=

x

2

y = x^2

y=x2. Now let

d

x

dx

dx be a miscellaneous infinitesimals (it is the same no matter which you choose if your function is differentiate-able at that point.)

在大多数表述中,

d

x

d

y

\frac{dx}{dy}

dydx 不能被解释为一个比率,因为

d

x

dx

dx 和

d

y

dy

dy 在其中实际上并不存在。这本书中展示了一个例外。正如阿图罗所说,它的工作原理是我们允许无穷小量(通过使用超实数系统)。它的表述很完善,比起极限概念我更喜欢它,因为这就是它被发明的方式。只是那时他们无法正确地表述它。我将举一个稍微简化的例子。假设你正在对

y

=

x

2

y = x^2

y=x2 求导。现在让

d

x

dx

dx 是一个任意的无穷小量(如果你的函数在该点可导,无论你选择哪个无穷小量,结果都是一样的)。

d y = ( x + d x ) 2 − x 2 dy = (x + dx)^2 - x^2 dy=(x+dx)2−x2

d y = 2 x × d x + d x 2 dy = 2x \times dx + dx^2 dy=2x×dx+dx2

Now when we take the ratio, it is:

现在当我们取比率时,它是:

d y d x = 2 x + d x \frac{dy}{dx} = 2x + dx dxdy=2x+dx

(Note: Actually,

Δ

y

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy is what we found in the beginning, and

d

y

dy

dy is defined so that

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is

Δ

y

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy rounded to the nearest real number.)

(注意:实际上,

Δ

y

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy 是我们一开始得到的,而

d

y

dy

dy 的定义是使得

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是

Δ

y

Δ

x

\frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}

ΔxΔy 四舍五入到最近的实数。)

edited Jan 21, 2021 at 2:29

answered Sep 19, 2013 at 23:47

Christopher King

So, your example is still incomplete. To complete it, you should either take the limit of

d

x

→

0

dx \to 0

dx→0 or take standard part of the RHS if you treat

d

x

dx

dx as infinitesimal instead of as

ϵ

\epsilon

ϵ.

所以,你的例子仍然不完整。要完善它,你要么取

d

x

→

0

dx \to 0

dx→0 的极限,要么如果你把

d

x

dx

dx 当作无穷小量而不是

ϵ

\epsilon

ϵ,就取右边的标准部分。

– Ruslan

Commented May 8, 2018 at 19:49

@Ruslan

d

x

dx

dx is a value, not a dummy variable in a limit.

@鲁斯兰

d

x

dx

dx 是一个值,不是极限中的哑变量。

– Christopher King

Commented Jan 21, 2021 at 2:33

I agree with @Ruslan.

d

x

dx

dx is not a value. There is no real number representing

d

x

dx

dx; it is an infinitesimal. Likewise, limits really contain no dummy variables either; they are essentially infinitesimals. Whether in standard analysis or nonstandard analysis, you must take the limit of

d

x

dx

dx (in standard analysis this would be represented as

h

h

h) or else this equality would not be useful in any way since there is no real number to represent

d

x

dx

dx. It is also very important to note, given

y

y

y is a dependent variable and

x

x

x is an independent variable,

Δ

y

≠

d

y

\Delta y \neq dy

Δy=dy, but

Δ

x

=

d

x

\Delta x = dx

Δx=dx.

我同意 @鲁斯兰的观点。

d

x

dx

dx 不是一个值。没有实数能代表

d

x

dx

dx;它是一个无穷小量。同样,极限实际上也不包含哑变量;它们本质上是无穷小量。无论是在标准分析还是非标准分析中,你都必须取

d

x

dx

dx 的极限(在标准分析中这会表示为

h

h

h),否则这个等式将毫无用处,因为没有实数能代表

d

x

dx

dx。还需要特别注意的是,鉴于

y

y

y 是因变量,

x

x

x 是自变量,

Δ

y

≠

d

y

\Delta y \neq dy

Δy=dy,但

Δ

x

=

d

x

\Delta x = dx

Δx=dx。

– Shidouuu

Commented Apr 21, 2023 at 0:40

@Shidouu nonstandard analysis is based on the hyperreal number system.

d

x

dx

dx is not a real number, nor is it a variable for a real number. It is a hyperreal.

@志堂 非标准分析基于超实数系统。

d

x

dx

dx 不是实数,也不是实数的变量。它是一个超实数。

– Christopher King

Commented Apr 21, 2023 at 18:29

I never said

d

x

dx

dx was a real number. I said it was an infinitesimal, which is a hyperreal.

我从未说过

d

x

dx

dx 是一个实数。我说它是一个无穷小量,而无穷小量是超实数。

– Shidouuu

Commented Apr 22, 2023 at 9:03

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is not a ratio - it is a symbol used to represent a limit.

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 不是一个比率——它是一个用来表示极限的符号。

answered Nov 5, 2011 at 3:15

GdS

This is one possible view on

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy, related to the fact that the common number system does not contain infinitesimals, making it impossible to justify this symbol as a ratio in that particular framework. However, Leibniz certainly meant it to be a ratio. Furthermore, it can be justified as a ratio in modern infinitesimal theories, as mentioned in some of the other answers.

这是对

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 的一种可能的看法,这与常见的数系不包含无穷小量这一事实有关,使得在那个特定的框架中无法将这个符号证明为一个比率。然而,莱布尼茨肯定是想让它成为一个比率。此外,正如其他一些答案中提到的,在现代无穷小理论中,它可以被证明是一个比率。

– Mikhail Katz

Commented Nov 17, 2013 at 14:57

I realize this is an old post, but I think it’s worth while to point out that in the so-called Quantum Calculus

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is a ratio. The subject starts off immediately by saying this is a ratio, by defining differentials and then calling derivatives a ratio of differentials:

我意识到这是一个旧帖子,但我认为值得指出的是,在所谓的量子微积分中,

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是一个比率。这门学科一开始就说它是一个比率,通过定义微分,然后称导数是微分的比率:

The

q

q

q-differential is defined as

q

q

q-微分定义为

d q f ( x ) = f ( q x ) − f ( x ) d_q f(x) = f(qx) - f(x) dqf(x)=f(qx)−f(x)

and the

h

h

h-differential as

而

h

h

h-微分定义为

d h f ( x ) = f ( x + h ) − f ( x ) d_h f(x) = f(x + h) - f(x) dhf(x)=f(x+h)−f(x)

It follows that

d

q

x

=

(

q

−

1

)

x

d_q x = (q - 1)x

dqx=(q−1)x and

d

h

x

=

h

d_h x = h

dhx=h.

由此可得

d

q

x

=

(

q

−

1

)

x

d_q x = (q - 1)x

dqx=(q−1)x 且

d

h

x

=

h

d_h x = h

dhx=h。

From here, we go on to define the

q

q

q-derivative and

h

h

h-derivative, respectively:

从这里,我们分别定义

q

q

q-导数和

h

h

h-导数:

D q f ( x ) = d q f ( x ) d q x = f ( q x ) − f ( x ) ( q − 1 ) x D_q f(x) = \frac{d_q f(x)}{d_q x} = \frac{f(qx) - f(x)}{(q - 1)x} Dqf(x)=dqxdqf(x)=(q−1)xf(qx)−f(x)

D h f ( x ) = d h f ( x ) d q x = f ( x + h ) − f ( x ) h D_h f(x) = \frac{d_h f(x)}{d_q x} = \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h} Dhf(x)=dqxdhf(x)=hf(x+h)−f(x)

Notice that

注意到

lim q → 1 D q f ( x ) = lim h → 0 D h f ( x ) = d f ( x ) x ≠ a r a t i o \lim_{q \to 1} D_q f(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} D_h f(x) = \frac{df(x)}{x} \neq a \ ratio limq→1Dqf(x)=limh→0Dhf(x)=xdf(x)=a ratio

edited Jan 16, 2015 at 6:43

answered Dec 28, 2013 at 1:51

Squirtle

I just want to point out that @Yiorgos S. Smyrlis did already state that

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is not a ratio, but a limit of a ratio (if it exists). I only included my response because this subject seems interesting (I don’t think many have heard of it) and in this subject we work in the confines of it being a ratio… but certainly the limit is not really a ratio.

我只想指出,@约尔戈斯·S·斯米尔利斯已经说过

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 不是一个比率,而是一个比率的极限(如果存在的话)。我之所以加入我的回答,是因为这个主题似乎很有趣(我认为很多人没有听说过),并且在这个主题中,我们在它是一个比率的范围内进行研究……但当然,这个极限并不是真正的比率。

– Squirtle

Commented Dec 28, 2013 at 1:54

You start out saying that it is a ratio and then end up saying that it is not a ratio. It’s interesting that you can define it as a limit of ratios in two different ways, but you’ve still only given it as a limit of ratios, not as a ratio directly.

你一开始说它是一个比率,最后又说它不是一个比率。有趣的是,你可以用两种不同的方式把它定义为比率的极限,但你仍然只是把它作为比率的极限来给出,而不是直接作为一个比率。

– Toby Bartels

Commented Apr 29, 2017 at 4:40

I guess you mean to say that the

q

q

q-derivative and

h

h

h-derivative are ratios; that the usual derivative may be recovered as limits of these is secondary to your point.

我猜你的意思是

q

q

q-导数和

h

h

h-导数是比率;而通常的导数可以作为这些的极限得到,这是次要的。

– Toby Bartels

Commented May 2, 2017 at 21:55

Yes, that is precisely my point.

是的,这正是我的观点。

– Squirtle

Commented Feb 23, 2018 at 4:04

To ask “Is

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy a ratio or isn’t it?” is like asking “Is

2

\sqrt{2}

2 a number or isn’t it?” The answer depends on what you mean by “number”.

2

\sqrt{2}

2 is not an Integer or a Rational number, so if that’s what you mean by “number”, then the answer is “No,

2

\sqrt{2}

2 is not a number.”

问“

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 是不是一个比率?”就像问“

2

\sqrt{2}

2 是不是一个数?”答案取决于你所说的“数”是什么意思。

2

\sqrt{2}

2 不是整数或有理数,所以如果你说的“数”是这个意思,那么答案是“不,

2

\sqrt{2}

2 不是一个数。”

However, the Real numbers are an extension of the Rational numbers that includes irrational numbers such as

2

\sqrt{2}

2, and so, in this set of numbers,

2

\sqrt{2}

2 is a number.

然而,实数是有理数的扩展,其中包括像

2

\sqrt{2}

2 这样的无理数,所以在这个数集中,

2

\sqrt{2}

2 是一个数。

In the same way, a differential such as

d

x

dx

dx is not a Real number, but it is possible to extend the Real numbers to include infinitesimals, and, if you do that, then

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is truly a ratio.

同样地,像

d

x

dx

dx 这样的微分不是实数,但可以扩展实数以包含无穷小量,如果你这样做了,那么

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 确实是一个比率。

When a professor tells you that

d

x

dx

dx by itself is meaningless, or that

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy is not a ratio, they are correct, in terms of “normal” number systems such as the Real or Complex systems, which are the number systems typically used in science, engineering and even mathematics. Infinitesimals can be placed on a rigorous footing, but sometimes at the cost of surrendering some important properties of the numbers we rely on for everyday science.

当教授告诉你

d

x

dx

dx 本身是没有意义的,或者

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 不是一个比率时,就“正常”的数系(如实数或复数系统)而言,他们是正确的,这些数系是科学、工程甚至数学中通常使用的数系。无穷小量可以被置于严格的基础上,但有时是以放弃我们日常科学所依赖的数的一些重要性质为代价的。

See infinitesimals for a discussion of number systems that include infinitesimals.

参见 infinitesimals 以讨论包含无穷小量的数系。

answered Nov 2, 2016 at 18:56

Hawthorne

Assuming you’re happy with

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy, when it becomes …

d

y

dy

dy… and …

d

x

dx

dx… it means that it follows that what precedes

d

y

dy

dy in terms of

y

y

y is equal to what precedes

d

x

dx

dx in terms of

x

x

x.

假设你对

d

y

d

x

\frac{dy}{dx}

dxdy 满意,当它变成……

d

y

dy

dy……和……

d

x

dx

dx……时,这意味着由此可得,就

y

y

y 而言在

d

y

dy

dy 前面的部分等于就

x

x

x 而言在

d

x

dx

dx 前面的部分。

“in terms of” = “with reference to”.

“就……而言”=“关于”。

That is, if “

a

d

y

d

x

=

b

a\frac{dy}{dx} = b

adxdy=b”, then it follows that “

a

a

a with reference to

y

y

y =

b

b

b with reference to

x

x

x”. If the equation has all the terms with

y

y

y on the left and all with

x

x

x on the right, then you’ve got to a good place to continue.

也就是说,如果“

a

d

y

d

x

=

b

a\frac{dy}{dx} = b

adxdy=b”,那么由此可得“关于

y

y

y 的

a

a

a = 关于

x

x

x 的

b

b

b”。如果方程左边所有项都含有

y

y

y,右边所有项都含有

x

x

x,那么你就到了一个可以继续下去的好地方。

The phrase “it follows that” means you haven’t really moved

d

x

dx

dx as in algebra. It now has a different meaning which is also true.