1.假设检验

差别大不大,大小和影响差别的干扰影响。

有些可能是由于误差上的改变

assumptions 前提条件

hypothesis 假设

连续变量才能做t检验

hypothesis 这个页面

hist(rbinom(100000, 100, .5), freq = F, main = "",

xlab = 'Number of head', ylab = 'Probability density')

t 检验也称为 Student t 检验,它是一种使用假设检验来评估一个或两个总体均值的工具。t 检验可用于评估某个组是否与已知值有差异(单样本 t 检验),两个组是否彼此有差异(独立双样本 t 检验),或成对测量值中是否存在显著差异(成对或非独立样本 t 检验)。

参考文献:https://www.jmp.com/zh_cn/statistics-knowledge-portal/t-test.html

daily.intake = c(5260,5470,5640,6180,6390,6515,

6805,7515,7515,8230,8770)

mean(daily.intake)

sd(daily.intake)

quantile(daily.intake)

t.test(daily.intake, mu = 7725)

# Nonparametric

wilcox.test(daily.intake, mu = 7725)

# Two samlpes

x1 = rnorm(300, 0, 1)

x2 = sample(0:100, 300, rep = T)

t.test(x1, x2)

# Check normality

plot(x1); hist(x1); qqnorm(x1)

shapiro.test(x1)

假设的整个过程

第一步:第一步需要是正态

第二步:条件:1.随机分布 2.连续取样 3.样本正态的。

做出两个假设,取样。

判断是否正态1.p值是否小于0.05 2.画图俩分析。

样本量增加会增加其特点,样本量足够大,能够显著性会提高。

第三步:

第五步:做出决定。

2.分析回顾

样本量很大

检验正态的分布

(1)如何判断样本是否正态

判断的方法

shapiro.test(x) #p>0.05

qqnorm(x) #straight line

shapiro.test(rnorm(5000, mean = 5, sd = 100))

shapiro.test(runif(30, min = 2, max = 4))

shapiro检验可能在任何大的样本中都显示是正态分布的,因而需要引入QQ图

y <- rnorm(200, sd = 10)

qqnorm(y)

qqline(y, col = 2)

极限中值定律,它的均值是符合正态分布的,这个是可以进行证明的。

# The central limit theorem

# Exponential distribution is a skewed distribution

y <- rexp(100); hist(y, col = 'grey')

# Define a vector with length 200

sample.mean <- numeric(200)

# The mean of 200 samples

for(i in 1:200) sample.mean[i] <- mean(rexp(100))

# A normal distribution appears

hist(sample.mean , col = 'grey')

shapiro.test(sample.mean)

(1)原假设的理解

和样本量无关,是根据图片来看,中间的分布比较多,两边比较少,认为就认为它是正态分布。

原假设必须等于,等于某个值就有个分布,不能大于。大于则分析其原因。分析统计量,最后来计算。

备择假设

计算统计量

pnorm(z)

t.test(x, mu=0, var.equal = T)

t检验

t.test(x, mu=0, var.equal = F)

自由度相当于样本量。自由度越大。样本量大于30认为是可以正态分布。

t分布与正态分布相似,t分布扁一点。(样本量少的时候,我们用t分布。)

# Plot a normal distribution and t distributions

x <- seq(-4, 4, len = 1000)

z <- dnorm(x, 0, 1)

plot(x, z, type = 'l', col = 'blue') # the normal curve

segments( 1.96, -0.05, 1.96, 0.1, col = 'brown')

segments(-1.96, -0.05,-1.96, 0.1, col = 'brown')

abline(0,0)

lines(x, dt(x, 15), col = 'green')

lines(x, dt(x, 4), col = 'red')

3.陈述假设检验

p值的情况

如何陈述

决策和结论

4.假设检验的“双尾”

T检验,分成了两边和左右两个方向

t.test(x, mu = 100, alt = "two.sided")

t.test(x, mu = 100, alt = "two.sided")

t.test(x, mu=100, alt = "greater")

t.test(x, mu=0, alt = "less")

p小于0.05就是可以推翻假设,用单尾可以更好地推翻结论。

前面是概率,后面是自由度。

qt(0.01, 22) # -2.508

prop.test(x, n, p, alternative = c("two.sided", "less", "greater"),conf.level = 0.95, correct = TRUE)

prop.test(0.77*300, 300, p=0.8)

5.配对检验

信息量多用z检验,t检验用于信息量比较。

配对检验,更容易有小p值,信息量表征越多,越可能拒绝原假设。

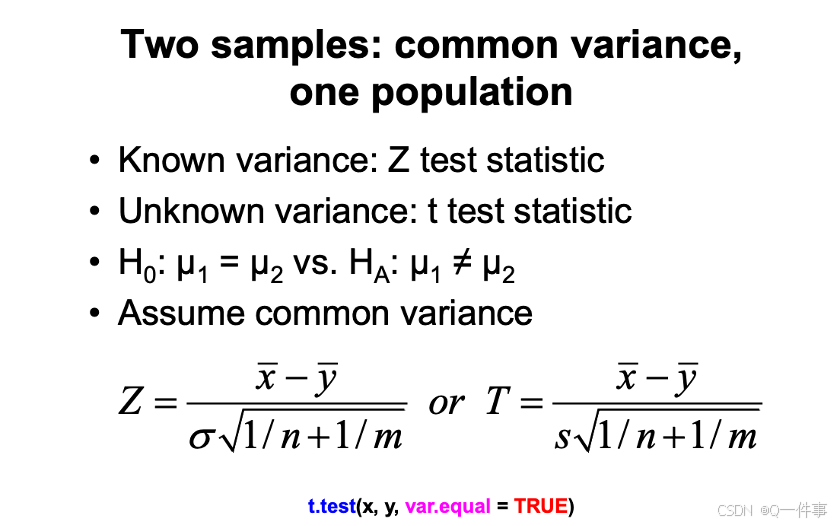

(1)不同情况下计算“双尾”

当方差相等的情况下

t.test(x, y, var.equal = TRUE)

方差不等的情况

t.test(x, y, var.equal = FALSE) # Welch’s t-test

(2)比例关系的检验

比例关系的方差

prop.test(12, 24, p=0.5) # it is a chi square test

两个不同的情况下,比例关系检验

比例关系用的是卡方检验。

x = sample(c('A','B'), 50, rep = T)

y = sample(c('F','M'), 50, rep = T)

table(x,y)

prop.test(table(x,y), correct = TRUE)

# 比例不显著

prop.test(table(x,y), correct = TRUE)

pbinom(8-1, 20, .25, lower.tail = F) = 0.1018

正式假设检验的步骤

最后的公式,()是单双尾,v是自由度

t.test(B, C, var.equal = TRUE)

方差的计算,自由度可以

t.test(present, newer, alt=“less”, var.equal = T)

t分布和f分布的关系。

6.作业

7.作业

lines <-

"ID x y

1 208 197

2 202 150

3 203 255

4 200 134

5 205 266

6 206 200

7 207 189

8 208 186

9 203 215

10 210 199"

weight <- read.table(con <- textConnection(lines), header=TRUE)

close(con)

# check data

weight

head(weight)

# t test

t.test(weight$x, weight$y, var.equal = F) # two samples

t.test(weight$x, mu = 200) # one sample

shapiro.test(weight$x) # check normal distribution

shapiro.test(weight$y)

hist(weight$y)

因为上面说到了T检验,因而进行回顾一下。

什么是 t 检验?

t 检验也称为 Student t 检验,它是一种使用假设检验来评估一个或两个总体均值的工具。t 检验可用于评估某个组是否与已知值有差异(单样本 t 检验),两个组是否彼此有差异(独立双样本 t 检验),或成对测量值中是否存在显著差异(成对或非独立样本 t 检验)。

如何使用 t 检验?

首先,定义您将要检验的假设,并指定一个可接受的、得出错误结论的风险。例如,比较两个总体时,您可能会假设它们的均值相同,并且您要确定一个可接受的得出错误结论(即不存在差异时认为存在差异)的概率。接下来,您要基于数据计算检验统计量,并将其与来自 t 分布的理论值进行比较。根据结果而定,您要么拒绝原假设,要么无法拒绝原假设。

如果有两个以上的组,该怎么办?

t 检验不适合。请使用多重比较方法。例如:方差分析 (ANOVA)、Tukey-Kramer 配对比较、与单个对照进行比较的 Dunnett’s 检验以及均值分析 (ANOM)。

# Load necessary library

library(ggplot2)

# Define the gravitational constant

G <- 6.67430e-11 # in m^3 kg^-1 s^-2

# Function to calculate gravitational force

gravity_force <- function(m1, m2, r) {

return(G * (m1 * m2) / r^2)

}

# Define masses and range of distances

m1 <- 5.97e24 # Mass of the Earth in kg

m2 <- 7.35e22 # Mass of the Moon in kg

distance <- seq(1e6, 4e8, by=1e7) # Distance in meters from 1 million to 400 million meters

# Calculate gravitational forces

force <- gravity_force(m1, m2, distance)

# Create a data frame for plotting

data <- data.frame(distance = distance, force = force)

# Plot the gravitational force vs distance

ggplot(data, aes(x = distance, y = force)) +

geom_line(color = "blue") +

labs(title = "Gravitational Force vs Distance",

x = "Distance (m)",

y = "Gravitational Force (N)") +

theme_minimal()

236

236

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?