1.1 Getting Started

1.1.1 Programming in Python

Python is a prominent as well as widely used language which can be used in web, game, science and etc. (which can be well illustrated in the first chapter of this ✬Python3 Tutorial✬ and ✬the Zen of Python✬)

1.1.2 Installing Python

1.1.3 Interactive Sessions

Type python at a terminal prompt and an interactive session can be started.

Interactive controls:

To access your typing history, press <Control>-P (previous) and <Control>-N (next).

<Control>-D exits a session, which discards this history.

Up and down arrows also cycle through history.

1.1.4 First Example

Statements & Expressions: Python code consists of expressions and statements.

(Computer programs consist sentenses to compute value and carry out action)

Statements typically describe actions. (not evaluated but executed)

Expressions typically describe computations. (evaluated)

Functions:

Functions encapsulate logic that manipulates data.

Objects:

An object seamlessly bundles together data and the logic that manipulates that data. (which will be further discussed in Chapter 2.)

Interpreters:

Programs to implement such a procedure that evaluates compound expressions. (which will be further discussed in Chapter 3.)

✬ In the end, we will find that all of these core concepts are closely related: functions are objects, objects are functions, and interpreters are instances of both. However, developing a clear understanding of each of these concepts and their role in organizing code is critical to mastering the art of programming.

1.1.5 Errors

The nature of computers is described in ✬Stanford's intorductory course✬ as "powerful + stupid".

Some guiding principles of debugging:

- Test incrementally

- Isolate errors

- Check assumptions

- Consult others

1.2 Elements of Programming

Every powerful language has three such mechanisms:

- primitive expressions and statements

- means of combination

- means of abstraction

In programming, we deal with two kinds of elements: functions and data. (But they can be not so distinct)

1.2.1 Expressions

Mathematical expressions can use infix notation, where the operator (e.g., +, -, *, or /) appears in between the operands (numbers).

1.2.2 Call Expressions

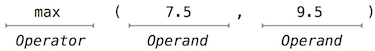

A call expression has subexpressions: the operator is an expression that precedes parentheses, which enclose a comma-delimited list of operand expressions.

(The function max is called with arguments 7.5 and 9.5, and returns a value of 9.5.)

Function's advantages compared with infix notation:

- Functions can take an arbitrary number of arguments.

- Function notation extends in a straightforward way to nested expressions.

1.2.3 Importing Library Functions

To use the elements that comprise the Python Library, one imports them.

eg.

>>> from math import sqrt

>>> sqrt(256)

16.0>>> from operator import add, sub, mul

>>> add(14, 28)

42

>>> sub(100, mul(7, add(8, 4)))

16More can be found in the ✬Python 3 Library Docs✬.

1.2.4 Names and the Environment

If a value(function) has been given a name, we say that the name binds to the value(function). (the assignment operator: "=", whose life purpose is to bind a name to a value)

The memory that keeps track of the names, values and bindings is called an environment.

A typical difference between python and C++:

In order to change a and b in python, you only need to:

>>> x, y = 3, 4.5

>>> y, x = x, y1.2.5 Evaluating Nested Expressions

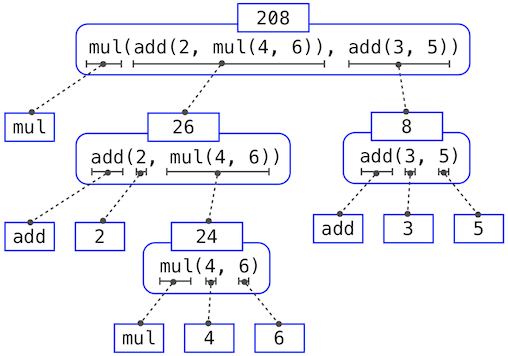

To evaluate a call expression, Python will:

- Evaluate the operator and operand subexpressions.

- Apply the function that is the value of the operator subexpression to the arguments that are the values of the operand subexpressions.

eg. an expression tree

1.2.6 The Non-Pure Print Function

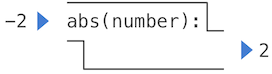

Pure functions:

Functions have some input (their arguments) and return some output (the result of applying them). (Reliable in compound call expressions) (Concurrent programs will be discussed in Chapter 4, where pure functions exert massive benefits.)

eg. abs()

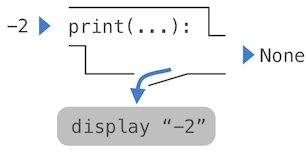

Non-pure functions:

Applying a non-pure function can generate side effects, which make some change to the state of the interpreter or computer.

eg. print()

An eloquent example:

>>> print(print(1), print(2))

1

2

None None1.3 Defining New Functions

How to define a function:

Function definitions consist of a def statement that indicates a <name> and a comma-separated list of named <formal parameters>, then a return statement, called the function body, that specifies the <return expression> of the function, which is an expression to be evaluated whenever the function is applied:

def <name>(<formal parameters>):

return <return expression>Both def statements and assignment statements bind names to values, and any existing bindings are lost.

1.3.1 Environments

An environment in which an expression is evaluated consists of a sequence of frames.

Each frame contains bindings, each of which associates a name with its corresponding value.

There is a single global frame.

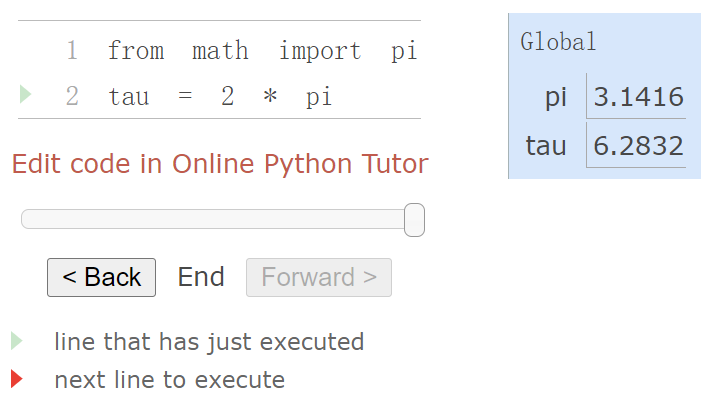

eg. An environment diagram (available in ✬Online Python Tutor✬)

The name appearing in the function(the box) is called the intrinsic name.

The name in a frame is a bound name.

Function Signatures:

A description of the formal parameters of a function.

1.3.2 Calling User-Defined Functions

Evaluating a user-defined function follows a computional procedure:

- Bind the arguments to the names of the function's formal parameters in a new local frame.

- Execute the body of the function in the environment that starts with this frame.

Name Evaluation:

A name evaluates to the value bound to that name in the earliest frame of the current environment in which that name is found.

1.3.3 Example: Calling a User-Defined Function

1.3.4 Local Names

The choice of the names for formal parameters does not affect one function's behaviour, since they remain local to the body of a function.

In other words, the scope of a local name is limited to the body of the user-defined function that defines it. When a name is no longer accessible, it is out of scope.

1.3.5 Choosing Names

Well-chosen function and parameter names are essential for the human interpretability of function definitions. (Pay attention to the ✬style guide for Python code✬.)

Basic and Recommended Guidelines:

- Function names are lowercase, with words separated by underscores. Descriptive names are encouraged.

- Function names typically evoke operations applied to arguments by the interpreter (eg. print, add, square) or the name of the quantity that results (eg. max, abs, sum).

- Parameter names are lowercase, with words separated by underscores. Single-word names are preferred.

- Parameter names should evoke the role of the parameter in the function, not just the kind of argument that is allowed.

- Single letter parameter names are acceptable when their role is obvious, but avoid "l" (lowercase ell), "O" (capital oh), or "I" (capital i) to avoid confusion with numerals.

1.3.6 Functions as Abstractions

We can write a function without concerning ourselves with how to achieve it. The details of how the action is designed can be suppressed, to be considered at a later time, which is a so-called functional abstraction.

Note: A function definition should be able to suppress details.

Aspects of a functional abstraction: Three core attributes should be considered.

- The domain of a function is the set of arguments it can take.

- The range of a function is the set of values it can return.

- The intent of a function is the relationship it computes between inputs and output (as well as any side effects it might generate).

1.3.7 Operators

Python expressions with infix operators can often be thought of as short-hand for call expressions. (eg. 2 + 3 is short for add(2, 3))

Note: The // operator rounds the result down to an integer. (eg. 5 // 4 == 1)

1.4 Designing Functions

We now concentrate on the topic of what makes a good function.

Fundamentally, the qualities of good functions all reinforce the idea that functions are abstractions.

- Each function should have exactly one job. That job should be identifiable with a short name and characterizable in a single line of text. In other words, functions that perform multiple jobs in sequence should be divided into multiple functions.

- Don't repeat yourself(DRY) is a central tenet of software engineering. Same logics should be implemented only once, given a name, and applied multiple times.

- Functions should be defined generally. Squaring is not in the Python Library precisely because it is a special case of the pow function, which raises numbers to arbitrary powers.

1.4.1 Documentation

A function definition will often include documentation describing the function, called a docstring, which must be indented along with the function body. (Referring to ✬docstring guidelines✬)

eg.

>>> def pressure(v, t, n):

"""Compute the pressure in pascals of an ideal gas.

Applies the ideal gas law: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ideal_gas_law

v -- volume of gas, in cubic meters

t -- absolute temperature in degrees kelvin

n -- particles of gas

"""

k = 1.38e-23 # Boltzmann's constant

return n * k * t / vWhen you call help with the name of a function as an argument, you see its docstring (type q to quit Python help).

eg.

>>> help(pressure)Comments:

Comments in Python can be attached to the end of a line following the # symbol. (which don't ever appear in Python's help, and they are ignored by the interpreter.)

1.4.2 Default Argument Values

eg. the variable n has a default value.

>>> def pressure(v, t, n=6.022e23):

"""Compute the pressure in pascals of an ideal gas.

v -- volume of gas, in cubic meters

t -- absolute temperature in degrees kelvin

n -- particles of gas (default: one mole)

"""

k = 1.38e-23 # Boltzmann's constant

return n * k * t / vNote: The = symbol in the def statement indicates a default value to use when the pressure function is called. (not performing assignment)

1.5 Control

Control statements will give us the ability to make comparisons and to perform different operations depending on the result of a comparison.

1.5.1 Statements

Rather than being evaluated, statements are executed, and executing statements can involve evaluating subexpressions contained within them. (Expressions can also be executed as statements, in which case they are evaluated, but their value is discarded.)

1.5.2 Compound Statements

In general, Python code is a sequence of statements.

A compound statement is so called because it is composed of other statements (simple and compound). Compound statements typically span multiple lines and start with a one-line header ending in a colon, which identifies the type of statement.

<header>:

<statement>

<statement>

...

<separating header>:

<statement>

<statement>

...

...eg. assignment statements are simple statements; def is a <header>

We say that the header controls its suite(a set of <statement>s), and a header and an indented suite of statements is called a clause.

Practical Guidance:

When indenting a suite, all lines must be indented the same amount and in the same way (use spaces, not tabs (WHY?)). Any variation in indentation will cause an error.

1.5.3 Defining Functions II: Local Assignment

Assignment statements within a function body cannot affect the global frame.

1.5.4 Conditional Statements

Conditional statements: a series of headers + suites

if <expression>:

<suite>

elif <expression>:

<suite>

else:

<suite>Boolean contexts:

The expressions inside the header statements of conditional blocks are said to be in boolean contexts: their truth values matter to control flow, but otherwise their values are not assigned or returned.

Boolean values:

True and False. The built-in comparison operations, >, <, >=, <=, ==, !=, return these values.

Boolean operators:

and, or and not

Short-circuiting feature:

To evaluate the expression <left> and <right>:

- Evaluate the subexpression <left>.

- If the result is a false value v, then the expression evaluates to v.

- Otherwise, the expression evaluates to the value of the subexpression <right>.

To evaluate the expression <left> or <right>:

- Evaluate the subexpression <left>.

- If the result is a true value v, then the expression evaluates to v.

- Otherwise, the expression evaluates to the value of the subexpression <right>.

To evaluate the expression not <exp>:

- Evaluate <exp>; The value is True if the result is a false value, and False otherwise.

1.5.5 Iteration

Iterative control structures are another mechanism for executing the same statements many times.

eg. Fibonacci Number

>>> def fib(n):

"""Compute the nth Fibonacci number, for n >= 2."""

pred, curr = 0, 1 # Fibonacci numbers 1 and 2

k = 2

while k < n:

pred, curr = curr, pred + curr

k = k + 1

return curr

>>> result = fib(8)A while clause contains a header expression followed by a suite:

while <expression>:

<suite>To execute a while clause:

- Evaluate the header's expression.

- If it is a true value, execute the suite, then return to step 1.

Note: Press <Control>-C to force Python to stop looping.

1.5.6 Testing

Testing a function is the act of verifying that the function's behavior matches expectations.

A test is a mechanism for systematically performing this verification.

Assertions:

Programmers use assert statements to verify expectations, such as the output of a function being tested. An assert statement has an expression in a boolean context, followed by a quoted line of text (single or double quotes are both fine, but be consistent) that will be displayed if the expression evaluates to a false value.

eg. Asserting Fibonacci number

>>> assert fib(8) == 13, 'The 8th Fibonacci number should be 13'>>> def fib_test():

assert fib(2) == 1, 'The 2nd Fibonacci number should be 1'

assert fib(3) == 1, 'The 3rd Fibonacci number should be 1'

assert fib(50) == 7778742049, 'Error at the 50th Fibonacci number'Note: When writing Python in files, rather than directly into the interpreter, tests are typically written in the same file or a neighboring file with the suffix _test.py.

Doctests: A convenient approach to place simple tests.

The first line of a docstring should contain a one-line description of the function, followed by a blank line. A detailed description of arguments and behavior may follow. In addition, the docstring may include a sample interactive session that calls the function.

eg. Summing naturals

>>> def sum_naturals(n):

"""Return the sum of the first n natural numbers.

>>> sum_naturals(10)

55

>>> sum_naturals(100)

5050

"""

total, k = 0, 1

while k <= n:

total, k = total + k, k + 1

return totalThen, the interaction can be verified via the ✬doctest module✬.

eg.

>>> from doctest import testmod

>>> testmod()

TestResults(failed=0, attempted=2)To verify the doctest interactions for only a single function, we use a doctest function called run_docstring_examples, whose first argument is the function to test, second should always be the result of the expression globals(), a built-in function that returns the global environment, which the interpreter needs in order to evaluate expressions, and third argument is True to indicate that we would like "verbose" output: a catalog of all tests run.

eg.

>>> from doctest import run_docstring_examples

>>> run_docstring_examples(sum_naturals, globals(), True)

Finding tests in NoName

Trying:

sum_naturals(10)

Expecting:

55

ok

Trying:

sum_naturals(100)

Expecting:

5050

okWhen writing Python in files, all doctests in a file can be run by starting Python with the doctest command line option:

python -m doctest <python_source_file>Note: The key to effective testing is to write (and run) tests immediately after implementing new functions. A test that applies a single function is called a unit test. And Exhaustive unit testing is a hallmark of good program design.

1.6 Higher-Order Functions

One of the things we should demand from a powerful programming language is the ability to build abstractions by assigning names to common patterns and then to work in terms of the names directly. (Functions work!)

1.6.1 Functions as Arguments

Consider the following three functions:

eg1. Compute natural numbers' summations

>>> def sum_naturals(n):

total, k = 0, 1

while k <= n:

total, k = total + k, k + 1

return total

>>> sum_naturals(100)

5050eg2. Compute natural cubes' summations

>>> def sum_cubes(n):

total, k = 0, 1

while k <= n:

total, k = total + k*k*k, k + 1

return total

>>> sum_cubes(100)

25502500eg3. Compute 8/(2n-1)*(2n+1) summations

>>> def pi_sum(n):

total, k = 0, 1

while k <= n:

total, k = total + 8 / ((4*k-3) * (4*k-1)), k + 1

return total

>>> pi_sum(100)

3.1365926848388144They clearly share a common underlying pattern. So they can be abstracted into one function.

eg. Abstract version of summation

>>> def summation(n, term):

total, k = 0, 1

while k <= n:

total, k = total + term(k), k + 1

return total

>>> def identity(x):

return x

>>> def sum_naturals(n):

return summation(n, identity)

>>> sum_naturals(10)

551.6.2 Functions as General Methods

Two big ideas in computer science:

- Names and functions allow us to abstract away a vast amount of complexity.

- It is only by virtue of the fact that we have an extremely general evaluation procedure for the Python language that small components can be composed into complex processes.

1.6.3 Defining Functions III: Nested Definitions

Without nested definitions, the global frame would become cluttered with names of small functions, which must all be unique and we would be constrained by particular function signatures. Nested function definitions address both of these problems.

eg. Compute the square root of a number

>>> def sqrt(a):

def sqrt_update(x):

return average(x, a/x)

def sqrt_close(x):

return approx_eq(x * x, a)

return improve(sqrt_update, sqrt_close)Like local assignment, local def statements only affect the current local frame.

Lexical scope:

Locally defined functions also have access to the name bindings in the scope in which they are defined. In the upper example, sqrt_update refers to the name a, which is a formal parameter of its enclosing function sqrt (locally defined functions are often called closures). This discipline of sharing names among nested definitions is called lexical scoping.

Two extensions to the model in order to enable lexical scoping:

- Each user-defined function has a parent environment: the environment in which it was defined.

- When a user-defined function is called, its local frame extends its parent environment.

Extended Environments:

An environment can consist of an arbitrarily long chain of frames, which always concludes with the global frame.

Two key advantages of lexical scoping:

- The names of a local function do not interfere with names external to the function in which it is defined, because the local function name will be bound in the current local environment in which it was defined, rather than the global environment.

- A local function can access the environment of the enclosing function, because the body of the local function is evaluated in an environment that extends the evaluation environment in which it was defined.

1.6.4 Functions as Returned Values

An important feature of lexically scoped programming languages is that locally defined functions maintain their parent environment when they are returned.

Once many simple functions are defined, function composition is a natural method of combination to include in our programming language. That is, given two functions f(x) and g(x), we might want to define h(x) = f(g(x)).

eg. h(x) = f(g(x))

>>> def compose1(f, g):

def h(x):

return f(g(x))

return hNote: The 1 in compose1 is meant to signify that the composed functions all take a single argument. (which is just part of the function name.)

1.6.5 Example: Newton's Method

1.6.6 Currying

We can use higher-order functions to convert a function that takes multiple arguments into a chain of functions that each take a single argument, which is called currying. In other words, given a function f(x, y), we can define a function g such that g(x)(y) is equivalent to f(x, y), where g is a higher-order function that takes in a single argument x and returns another function that takes in a single argument y.

Currying is useful when we require a function that takes in only a single argument.

eg. Automate currying and uncurrying

>>> def curry2(f):

"""Return a curried version of the given two-argument function."""

def g(x):

def h(y):

return f(x, y)

return h

return g

>>> def uncurry2(g):

"""Return a two-argument version of the given curried function."""

def f(x, y):

return g(x)(y)

return f1.6.7 Lambda Expressions

We can create function values on the fly using lambda(λ) expressions, which evaluate to unnamed functions. (where assignment and control statements are not allowed.)

eg. lambda

>>> def compose1(f, g):

return lambda x: f(g(x))>>> compose1 = lambda f,g: lambda x: f(g(x))lambda's syntax:

lambda x : f(g(x))

"A function that takes x and returns f(g(x))"1.6.8 Abstractions and First-Class Functions

As programmers, we should be alert to opportunities to identify the underlying abstractions in our programs, build upon them, and generalize them to create more powerful abstractions.The significance of higher-order functions is that they enable us to represent these abstractions explicitly as elements in our programming language, so that they can be handled just like other computational elements.

1.6.9 Function Decorators

Python provides special syntax to apply higher-order functions as part of executing a def statement, called a decorator.

eg. Trace

>>> def trace(fn):

def wrapped(x):

print('-> ', fn, '(', x, ')')

return fn(x)

return wrapped

>>> @trace

def triple(x):

return 3 * x

>>> triple(12)

-> <function triple at 0x102a39848> ( 12 )

36The def statement for triple has an annotation, @trace, which affects the execution rule for def. As usual, the function triple is created. However, the name triple is not bound to this function. Instead, the name triple is bound to the returned function value of calling trace on the newly defined triple function. In code, this decorator is equivalent to:

>>> def triple(x):

return 3 * x

>>> triple = trace(triple)More information about decorators can be found in the ✬short tutorial on decorators✬.

1.7 Recursive Functions

A function is called recursive if the body of the function calls the function itself, either directly or indirectly.

An example problem: write a function that sums the digits of a natural number.

>>> def sum_digits(n):

"""Return the sum of the digits of positive integer n."""

if n < 10:

return n

else:

all_but_last, last = n // 10, n % 10

return sum_digits(all_but_last) + last1.7.1 The Anatomy of Recursive Functions

A common pattern can be found in the body of many recursive functions:

- The body begins with a base case, a conditional statement that defines the behavior of the function for the inputs that are simplest to process.

- The base cases are then followed by one or more recursive calls.

A recursive leap of faith:

Treat a recursive call as a functional abstraction. (That is to ignore how the function is implemented and trust that it works.)

1.7.2 Mutual Recursion

When a recursive procedure is divided among two functions that call each other, the functions are said to be mutually recursive.

eg. Even or odd

>>> def is_even(n):

if n == 0:

return True

else:

return is_odd(n-1)

>>> def is_odd(n):

if n == 0:

return False

else:

return is_even(n-1)

>>> result = is_even(4)eg. Single recursive version

>>> def is_even(n):

if n == 0:

return True

else:

if (n-1) == 0:

return False

else:

return is_even((n-1)-1)1.7.3 Printing in Recursive Functions

The computational process evolved by a recursive function can often be visualized using calls to print.

eg. Cascading

>>> def cascade(n):

"""Print a cascade of prefixes of n."""

if n < 10:

print(n)

else:

print(n)

cascade(n//10)

print(n)

>>> cascade(2013)

2013

201

20

2

20

201

20131.7.4 Tree Recursion

A function calling itself more than once is called tree recursion.

eg. Fibonacci number

>>> def fib(n):

if n == 1:

return 0

if n == 2:

return 1

else:

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1)

>>> result = fib(6)

7808

7808

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?