注:机翻,未校。

Postdocs’advice on pursuing a research career in academia: A qualitative analysis of free-text survey responses

2021 May 6

Suwaiba Afonja 1, Damonie G Salmon 1, Shadelia I Quailey 1, W Marcus Lambert 2,*

Editor: Frederick Grinnell3

-

Author information

-

Article notes

-

Copyright and License information

-

PMCID: PMC8101926 PMID: 33956818

Abstract 摘要

Background 背景

The decision of whether to pursue a tenure-track faculty position has become increasingly difficult for undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral trainees considering a career in research. Trainees express concerns over job availability, financial insecurity, and other perceived challenges associated with pursuing an academic position.

对于考虑从事研究事业的本科生、研究生和博士后实习生来说,是否追求终身教职的决定变得越来越困难。实习生对工作机会、财务不安全以及与追求学术职位相关的其他感知挑战表示担忧。

Methods 方法

To help further elucidate the benefits, challenges, and strategies for pursuing an academic career, a diverse sample of postdoctoral scholars (“postdocs”) from across the United States were asked to provide advice on pursuing a research career in academia in response to an open-ended survey question. 994 responses were qualitatively analyzed using both content and thematic analyses. 177 unique codes, 20 categories, and 10 subthemes emerged from the data and were generalized into two thematic areas: Life in Academia and Strategies for Success.

为了帮助进一步阐明追求学术事业的好处、挑战和策略,来自美国各地的不同样本博士后学者(“博士后”)被要求提供有关在学术界从事研究事业的建议,以回答一个开放式调查问题。使用内容和主题分析对 994 份回复进行了定性分析。从数据中产生了 177 个独特代码、20 个类别和 10 个子主题,并归纳为两个主题领域:学术界生活和成功战略。

Results 结果

On life in academia, postdoc respondents overwhelmingly agree that academia is most rewarding when you are truly passionate about scientific research and discovery. ‘Passion’ emerged as the most frequently cited code, referenced 189 times. Financial insecurity, work-life balance, securing grant funding, academic politics, and a competitive job market emerged as challenges of academic research. The survey respondents note that while passion and hard work are necessary, they are not always sufficient to overcome these challenges. The postdocs encourage trainees to be realistic about career expectations and to prepare broadly for career paths that align with their interests, skills, and values. Strategies recommended for perseverance include periodic self-reflection, mental health support, and carefully selecting mentors.

关于学术界的生活,绝大多数博士后受访者都认为,当你真正对科学研究和发现充满热情时,学术界是最有价值的。“Passion”成为被引用次数最多的代码,被引用了 189 次。财务不安全、工作与生活的平衡、获得赠款资金、学术政治和竞争激烈的就业市场成为学术研究的挑战。调查受访者指出,虽然热情和努力工作是必要的,但它们并不总是足以克服这些挑战。博士后鼓励受训者对职业期望持现实态度,并为符合他们的兴趣、技能和价值观的职业道路做好广泛准备。坚持不懈的推荐策略包括定期自我反省、心理健康支持和仔细选择导师。

Conclusions 结论

For early-career scientists along the training continuum, this advice deserves critical reflection before committing to an academic research career. For advisors and institutions, this work provides a unique perspective from postdoctoral scholars on elements of the academic training path that can be improved to increase retention, career satisfaction, and preparation for the scientific workforce.

对于处于培训连续体的早期职业科学家来说,在致力于学术研究事业之前,这个建议值得批判性地思考。对于顾问和机构,这项工作为博士后学者提供了关于学术培训路径要素的独特视角,可以改进这些要素以提高保留率、职业满意度和为科学工作者做好准备。

Introduction 介绍

Postdoctoral researchers (“postdocs”) seeking research faculty positions are facing increasing challenges in their career pursuits [1–5]. The first and most dynamic is the large number of postdocs competing for a limited number of faculty positions. In the early 1970s, the number of NIH principal investigators (PIs) was equivalent to the number of biomedical postdocs and exceeded the number of graduate student researchers by more than 50% [6]. Growing from 7,000 to over 21,000 biomedical postdocs today, some argue that there is an oversupply of postdocs and overemphasis of academic tracks, leading to a hypercompetitive culture among trainees for faculty positions [7, 8]. This oversaturation may be partially attributed to insufficient preparation of graduate students for career options outside of academia [9–12], leaving postdoctoral positions as a default career step for many PhD holders [13, 14]. Others maintain that postdoc oversaturation is a misperception as postdoc positions should not be considered only as preparation for an academic job but rather as an opportunity for skill development for a multitude of fields [10, 15–20]. In addition, the total number of tenure-track faculty positions has remained relatively constant over the past few decades, and the disparity between postdoctoral appointments and available tenure-track positions has not been proportionally adjusted for [6, 7, 21]. Currently, tenure-track faculty positions only represent approximately 15% of postdoc career outcomes [22].

寻求研究型教师职位的博士后研究人员(“博士后”)在他们的职业追求中面临着越来越大的挑战 [1 – 5]。首先也是最具活力的是大量的博士后争夺有限数量的教职职位。在 1970 年代初期,NIH 首席研究员(PI)的数量相当于生物医学博士后的数量,并且超过研究生研究人员的数量超过 50% [6]。生物医学博士后从 7,000 人增长到今天的 21,000 多名,一些人认为博士后供过于求,过分强调学术方向,导致受训者在教职职位上出现高度竞争的文化 [7,8]。这种过度饱和可能部分归因于研究生对学术界以外的职业选择的准备不足 [9 – 12],使博士后职位成为许多博士持有者的默认职业步骤 [13,14]。其他人则认为博士后过度饱和是一种误解,因为博士后职位不应仅被视为为学术工作的准备,而应被视为多个领域技能发展的机会 [10,15 – 20]。此外,在过去几十年中,终身教职职位的总数一直保持相对稳定,博士后任命和可用的终身教职职位之间的差异没有按比例进行调整 [6,7,21]。目前,终身教职仅占博士后职业成果的约 15% [22]。

Second among these growing challenges is the poor sense of financial security felt by many postdoctoral researchers. Previous reports note low salaries and a long overall training length for many postdocs [22, 23]. The postdoctoral position, intended to be a temporary training period, has been increasing in length without a substantial increase in pay, with recent studies reporting postdocs completing more than one postdoc [24, 25]. McConnell et al. [22] found that postdoctoral salaries are not maintaining parity with the cost of living increases. At the time of their study (2016), postdocs reported salaries in the range of 39,000–55,000 (median 43,750, mean 46,988) [22]. The financial sacrifices and increasing time commitment made during this training phase are compounded by a lengthy biomedical doctoral training period with a median time to degree of greater than 5 years [26].

在这些日益严峻的挑战中,第二个是许多博士后研究人员的财务安全感不佳。以前的报告指出,许多博士后的工资低且总体培训时间长 [22,23]。博士后职位本来是一个临时的培训期,但时间一直在增加,而工资却没有大幅增加,最近的研究报告称,博士后完成了不止一个博士后 [24,25]。McConnell 等人 [22] 发现,博士后工资与生活成本的增加并不相等。在他们研究时(2016 年),博士后报告的薪水在 39,000 美元至 55,000 美元之间(中位数 43,750 美元,平均 46,988 美元)[22]。在这个培训阶段做出的经济牺牲和增加的时间投入,加上漫长的生物医学博士培训期,获得学位的中位时间超过 5 年 [26]。

Over the last five years, the National Institutes of Health have increased the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) stipends by four to five percent on average for postdocs [27]. This adjustment is consistent with recommendations from the 2012 Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group report from the NIH and the 2018 Next Generation of Biomedical and Behavioral Sciences Researchers: Breaking Through report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine [27–29]. Many institutions are starting to follow suit, either using the NRSA levels as guidelines for setting postdoctoral salaries or setting the minimum in accordance with the Fair Labor Standards Act [30]. Historically low stipends and a sense of financial insecurity are associated with increased interest in non-academic careers [25].

在过去的五年中,美国国立卫生研究院已将博士后的 Ruth L. Kirschstein 国家研究服务奖(NRSA)津贴平均提高了 4% 到 5% [27]。这一调整与 NIH 的 2012 年生物医学研究劳动力工作组报告和 2018 年下一代生物医学和行为科学研究人员:美国国家科学、工程和医学学院的突破报告 [27 – 29] 中的建议一致。许多机构开始效仿,要么使用 NRSA 水平作为设定博士后工资的指导方针,要么根据《公平劳动标准法》设定最低工资 [30]。历史上较低的津贴和经济不安全感与对非学术职业的兴趣增加有关 [25]。

Researchers who begin a postdoctoral position despite awareness of the salary support and limited availability of faculty positions may still lose interest as their training progresses [31, 32]. Some evidence suggests this is due to the incompatibility between their career preferences and the demands of the academic lifestyle [9, 33]. Unrealistic expectations or lack of knowledge about aspects of academic life such as academic freedom, administrative obligations, funding, and the time commitment may cause many to prematurely abandon this track despite already committing a significant number of years to it [33]. With regard to women and underrepresented minority (URM) postdocs, the largest exit from the academic research pipeline can be observed in the first two years of postdoctoral training [25]. An increase in transparency about life in academia and the dissemination of more information on the critical steps for securing an academic research position should increase the retention of trainees by giving those who choose to commit to this track, despite the known challenges, the opportunity to make well-informed career decisions that reflect their personal and professional values [34].

尽管知道工资支持和教师职位有限,但开始从事博士后职位的研究人员仍可能随着培训的进展而失去兴趣 [31,32]。一些证据表明,这是由于他们的职业偏好与学术生活方式的要求之间的不相容 [9,33]。不切实际的期望或缺乏对学术生活的各个方面(如学术自由、行政义务、资金和时间投入)的了解,可能会导致许多人过早地放弃这条轨道,尽管他们已经为此付出了相当长的时间 [33]。关于女性和代表性不足的少数族裔(URM)博士后,可以在博士后培训的前两年观察到学术研究管道的最大退出 [25]。提高学术界生活的透明度,并传播更多关于获得学术研究职位的关键步骤的信息,应该可以提高受训者的保留率,让那些尽管面临已知挑战但选择投身这一轨道的人有机会做出反映其个人和职业价值观的明智职业决定 [34]。

Postdoctoral researchers can provide a unique perspective on the benefits and challenges of a research career. They are in a distinctive training period that serves as the branch point for their future careers and have personally experienced many of these benefits and challenges. Our previous work identified the most influential factors for those who intend to pursue teaching or non-academic career paths (this includes teaching-intensive faculty positions, non-academic research positions such as industry, non-research but science-related positions, and non-science related positions) [25]. Job prospects, financial security, responsibility to family, and mentorship from their PI were the most cited reasons for those opting for careers outside of academia [25]. Postdocs who pursue academic research careers produced significantly more publications (9 vs. 7, p<0.001), more first-author publications (4 vs. 3, p<0.001), and have a higher first-author publication rate (0.56 vs. 0.42, p<0.001), yet, a significant portion (40%) of even the most productive postdocs opt out of pursuing an academic career [25]. Thus, a greater understanding of how postdocs perceive the path to academic research independence is warranted. In addition, strategies to overcome the challenges faced along the way are also needed.

博士后研究人员可以就研究生涯的好处和挑战提供独特的视角。他们正处于一个独特的培训时期,这是他们未来职业生涯的分支,并且亲身经历了许多这些好处和挑战。我们之前的工作确定了对那些打算追求教学或非学术职业道路的人最有影响力的因素(这包括教学密集型教师职位、非学术研究职位,如行业、非研究但与科学相关的职位,以及非科学相关的职位)[25]。 工作前景、财务保障、对家庭的责任以及 PI 的指导是那些选择学术界以外职业的人被引用最多的原因 [25]。从事学术研究事业的博士后发表了更多的出版物(9 篇对 7 篇,第 <0.001 页),第一作者出版物更多(4 篇对 3 篇,<第 0.001 页),第一作者发表率更高(0.56 对 0.42,<0.001 页),然而,即使是最高效的博士后,也有很大一部分(40%)选择退出学术生涯 [25]。因此,有必要更深入地了解博士后如何看待通往学术研究独立的道路。此外,还需要制定策略来克服在此过程中面临的挑战。

This current study amasses the guidance and recommendations of 994 postdocs on pursuing an academic career. Our objectives are:

目前的这项研究收集了 994 名博士后关于追求学术生涯的指导和建议。我们的目标是:

- To understand how postdoctoral research trainees perceive the benefits and challenges of pursuing an academic research career;了解博士后研究实习生如何看待从事学术研究事业的好处和挑战;

- To provide ways to overcome these challenges.提供克服这些挑战的方法。

The advice gathered from the postdoctoral researchers in this study will help prospective trainees make more informed career decisions. Instead of only describing some of the obstacles they have faced, the postdocs provide numerous strategies and suggestions to help future and current researchers take greater control of their career outcomes. These primary accounts further elucidate many of the challenges researchers encounter when choosing career paths. Therefore, such disclosure can increase transparency about the benefits and challenges of pursuing a tenure-track faculty position and encourage a more efficient transition from training stages to careers across the scientific workforce.

本研究中从博士后研究人员那里收集的建议将帮助潜在的受训者做出更明智的职业决定。博士后不仅描述了他们面临的一些障碍,还提供了许多策略和建议,以帮助未来和当前的研究人员更好地控制他们的职业成果。这些主要叙述进一步阐明了研究人员在选择职业道路时遇到的许多挑战。因此,这种披露可以提高追求终身教职的好处和挑战的透明度,并鼓励整个科学工作者更有效地从培训阶段过渡到职业。

Methods 方法

U-MARC survey U-MARC 调查

Postdoctoral scholars (“postdocs”) in the biological and biomedical sciences from across the United States were invited to complete an original survey instrument entitled U-MARC (Understanding Motivations for Academic Research Careers) in July of 2017. The 70-item survey (1) measures views on determinants of career choice in science and (2) measures outcome expectations and self-efficacy around research careers using two original scales. The study’s theoretical framework was derived from (i) Social Cognitive Career Theory which states that self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and personal goals affect career decision and (ii) Vroom’s Expectancy Theory which infers that motivation is a result of how much an individual wants a reward (valence), the probability that a specific effort will lead to the expected performance (expectancy), and the belief that the performance will lead to the reward (instrumentality) [35, 36]. We used expectancy theory to build an outcome expectations instrument in the U-MARC survey, with some items taken from the Research Outcome Expectations Questions (ROEQ) [37]. For full details on the development of the U-MARC survey instrument, refer to our previous work (Lambert et al.) [25].

2017 年 7 月,来自美国各地的生物和生物医学科学博士后学者(“博士后”)被邀请完成了一份名为 U-MARC(了解学术研究职业的动机)的原始调查工具。这项包含 70 个项目的调查(1)衡量对科学职业选择决定因素的看法,以及(2)使用两个原始量表衡量研究职业的结果期望和自我效能感。该研究的理论框架源自(i)社会认知职业理论,该理论指出自我效能感、结果期望和个人目标会影响职业决策,以及(ii)Vroom 的期望理论,该理论推断动机是个人想要奖励的程度(效价)、特定努力导致预期绩效的概率(期望)、 以及相信表演将导致奖励(工具性)[35,36]。在 U-MARC 调查中,我们使用期望理论构建了结果期望工具,其中一些项目取自研究结果期望问题(ROEQ)[37]。有关 U-MARC 测量仪器开发的完整详细信息,请参阅我们以前的工作(Lambert 等人)。[25].

Data analysis 数据分析

In this study, we qualitatively coded 994 survey responses to an open-ended question from the U-MARC survey using hallmarks of both content analysis (examining patterns in text, highlighting frequency counts) and thematic analysis (interpreting themes within the data). The question states: “What advice would you give to someone thinking about an academic research career?” Two researchers were involved in the coding process, each independently deriving codes. A process of open, axial, and then selective coding was followed by generally coding and discussing major concepts, categories, and themes. A third researcher was consulted to help determine crosscutting themes and recurrent patterns, in consideration of analytic connectedness. We repeated this cycle until we achieved thematic saturation, and novel themes stopped emerging from the data. NVivo 12, a qualitative transcript software, was used to assist with the coding of the data.

在这项研究中,我们使用内容分析(检查文本中的模式,突出频率计数)和主题分析(解释数据中的主题)的标志,对 U-MARC 调查中一个开放式问题的 994 份调查回复进行了定性编码。问题指出:“你会给那些考虑从事学术研究事业的人什么建议?两名研究人员参与了编码过程,每个人都独立地推导出代码。一个开放的、轴向的、然后是选择性编码的过程,之后是一般编码和讨论主要概念、类别和主题。考虑到分析的连通性,咨询了第三位研究人员来帮助确定横切主题和重复出现的模式。我们重复这个循环,直到达到主题饱和,并且数据中不再出现新的主题。NVivo 12 是一种定性转录软件,用于协助数据编码。

Throughout the manuscript, we include transcript numbers corresponding to the survey respondents’ answers so readers can differentiate between the sources of any given set of quotations. The full list of responses and derived codes are included in the S1 Table.

在整个手稿中,我们包括与调查受访者的回答相对应的文字记录编号,以便读者可以区分任何给定引文集的来源。响应和派生代码的完整列表包含在 S1 表中 。

Data collection and sampling method数据收集和采样方法

All work was conducted under the approval of the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board (IRB# 1612017849), and all respondents self-selected and provided consent for participation in the study. A purposeful sampling strategy where participants were recruited through postdoctoral listservs from top-ranked research universities and institutions was used instead of snowball sampling, where existing participants would have recruited other potential candidates from their networks. All survey respondents self-selected to participate in the survey based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria previously published [25]. The sample represents wide geographic (over 80 universities) and subfield diversity. The number of institutions and the percentage of respondents from each institution were published in supplementary file 2 of our previous publication [25]. We also determined the percentage of respondents from highly-ranked life science research institutions in the US based on counts of high-quality research outputs between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017 according to rankings from Nature Index (Fig 1- figure supplement 1D) [25]. The majority of respondents are from highly-ranked US institutions, but the differences in institutional ranking do not fully account for the differences in career intention [25]. It should also be noted that postdoctoral appointees at the top 100 institutions in the United States (n = 56,092) account for approximately 88% of the total number of postdocs in the country (n = 63,861) [38]. From the total sample of participants who completed the U-MARC survey (n = 1248), only respondents who identified as a postdoctoral scholar or research associate were included in this analysis (n = 994). The sample postdoc participant pool represents 6% of the total amount (21,781) of appointed biomedical and biological postdocs the year the survey was conducted (2017) according to the National Science Foundation. The REDCap electronic data capture tool was used to collect and manage the 70-item anonymous U-MARC survey instrument. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.

所有工作均在威尔康奈尔医学院机构审查委员会(IRB# 1612017849)的批准下进行,所有受访者均自行选择并同意参与该研究。使用有目的的抽样策略,即参与者是通过顶级研究型大学和机构的博士后列表服务招募的,而不是滚雪球抽样,在滚雪球抽样中,现有参与者会从他们的网络中招募其他潜在候选人。所有调查受访者均根据先前发布的纳入和排除标准 [25] 自行选择参与调查。该样本代表了广泛的地理(80 多所大学)和子领域的多样性。机构的数量和每个机构的受访者百分比在我们之前出版物的补充文件 2 中公布 [25]。我们还根据自然指数的排名,根据 2017 年 1 月 1 日至 2017 年 12 月 31 日期间的高质量研究成果计数,确定了来自美国排名靠前的生命科学研究机构的受访者百分比(图 1 - 图补充 1D)[25]。大多数受访者来自排名靠前的美国机构,但机构排名的差异并不能完全解释职业意愿的差异 [25]。还应注意的是,美国排名前 100 的机构(n = 56,092)的博士后任命人员约占该国博士后总数的 88%(n = 63,861)[38]。在完成 U-MARC 调查的参与者总样本(n = 1248)中,只有被认定为博士后学者或研究助理的受访者被纳入该分析(n = 994)。根据美国国家科学基金会的数据,样本博士后参与者群体占调查进行当年(21,781 年)指定的生物医学和生物博士后总数(2017%)的 2017%。REDCap 电子数据采集工具用于收集和管理 70 项匿名 U-MARC 调查工具。REDCap(Research Electronic Data Capture)是一款基于 Web 的安全应用程序,旨在支持研究的数据捕获。

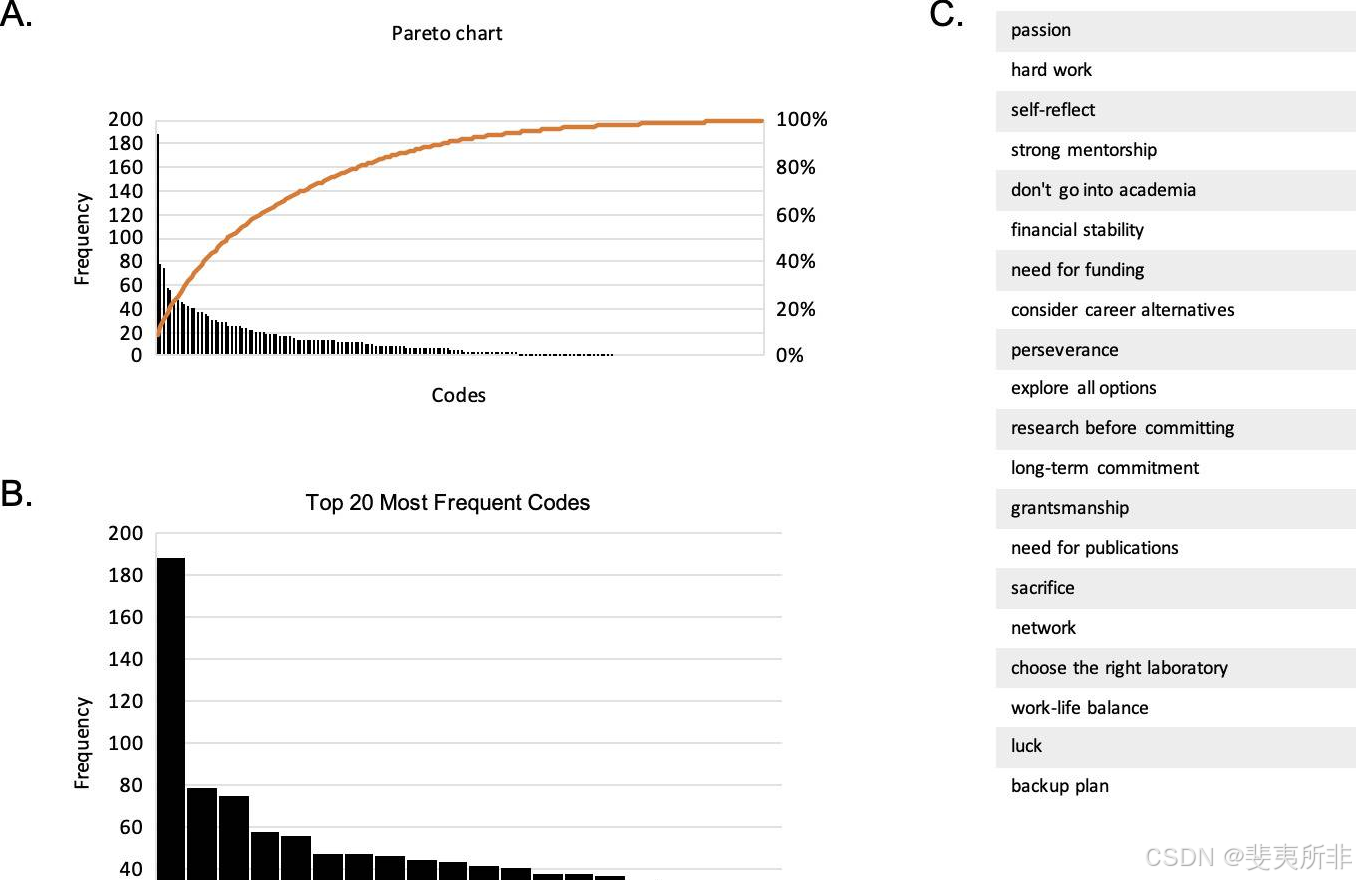

Fig 1. Relative frequency distribution of advice on pursuing an academic research career.

图 1.关于从事学术研究事业的建议的相对频率分布。

(A) To estimate the prevalence of advice from postdoc respondents, the frequency of the codes was analyzed and displayed by the bars (left axis) in descending order along with its contribution to the cumulative percentage, represented by the line (right axis). (B) The top 20 most frequent codes are displayed and © listed by frequency.

(A)为了估计博士后受访者建议的普遍性,分析了代码的频率,并按条形图(左轴)降序显示,以及它对累积百分比的贡献,由线(右轴)表示。(B)显示前 20 个最频繁的代码,并(C)按频率列出。

Results 结果

To establish a representative framework of life in academia at the postdoctoral stage of training and gather recommendations for success in this field, we asked postdoctoral candidates, “What advice would you give someone thinking about an academic research career?” The sample of 994 postdoctoral researchers included US citizens (n = 557, 56%), international fellows (n = 434, 44%), female postdocs (n = 615, 62%), male postdocs (n = 378, 38%), and underrepresented minorities (URM) postdocs (n = 174, 13%) (Table 1). URM postdocs include the racial and ethnic categories of American Indian or Alaska Native, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and/or Hispanic or Latino. The participants responded similarly across gender, race/ethnicity, and national status. The average time reported to earn a PhD in the biological or biomedical sciences for the postdoctoral respondents was 4.6 years, with an additional 2.7 years spent in postdoctoral training. The average time to PhD recorded here is lower than that of the national average due to the inclusion of the international students’ shorter doctoral training lengths.

为了在博士后培训阶段建立一个具有代表性的学术界生活框架,并收集在该领域取得成功的建议,我们询问了博士后候选人,“你会给那些考虑从事学术研究事业的人什么建议?994 名博士后研究人员的样本包括美国公民(n = 557,56%)、国际研究员(n = 434,44%)、女性博士后(n = 615,62%)、男性博士后(n = 378,38%)和代表性不足的少数族裔(URM)博士后(n = 174,13%)(表 1 )。URM 博士后包括美洲印第安人或阿拉斯加原住民、黑人或非裔美国人、夏威夷原住民或其他太平洋岛民和/或西班牙裔或拉丁裔的种族和民族类别。参与者在性别、种族/民族和国家地位方面的回答相似。据报道,博士后受访者获得生物或生物医学科学博士学位的平均时间为 4.6 年,另外还有 2.7 年用于博士后培训。由于国际学生的博士培训时间较短,因此这里记录的平均博士学习时间低于全国平均水平。

Table 1. Demographic information of survey participants.表 1.调查参与者的人口统计信息。

N = 994

| Female | 615 | 62% |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 378 | 38% |

| U.S. Citizen | 557 | 56% |

| International | 434 | 44% |

| Underrepresented minority | 133 | 13% |

| Average time to PhD | 4.6 | |

| Average time post-PhD | 2.7 |

With the information gathered from the 994 responses, 177 codes and 20 categories emerged. To estimate the prevalence of advice across postdoc respondents, we determined the frequency by which each code was cited (Fig 1A). ‘Passion’ emerged as the most frequently cited code, referenced 189 times across 994 responses, more than twice the amount of other codes (Fig 1B). The top 20 most frequently cited codes included: hard work, self-reflect, strong mentorship, don’t go into academia, financial stability, need for funding, consider career alternatives, perseverance, explore all options, research before committing, long-term commitment, grantsmanship, need for publications, sacrifice, network, choose the right laboratory, work-life balance, luck, and backup plan (Fig 1C). In the following text, we summarize the postdoc respondents’ advice across two major themes: Life in Academia and Strategies for Success.

根据从 994 份回复中收集的信息,出现了 177 个代码和 20 个类别。为了估计博士后受访者中建议的普遍性,我们确定了每个代码的引用频率(图 1A)。“Passion”成为被引用最多的代码,在 994 个回复中被引用了 189 次,是其他代码数量的两倍多(图 1B)。最常被引用的前 20 个代码包括:努力工作、自我反省、强大的指导、不要进入学术界、财务稳定、需要资金、考虑职业选择、毅力、探索所有选择、承诺前研究、长期承诺、资助、出版物需求、牺牲、网络、选择合适的实验室、工作与生活的平衡、运气和备用计划(图 1C)。在下文中,我们总结了博士后受访者对两个主要主题的建议:学术界生活和成功策略。

Life in academia 学术界的生活

Academia is a lifestyle 学术界是一种生活方式

According to the surveyed postdocs, a career in academia is not merely an occupation; it is a lifestyle (Table 2). The postdocs express that the time and commitment required for success in academia often shapes a researcher’s personal, professional, and social life:

根据接受调查的博士后,学术界的职业生涯不仅仅是一种职业;它是一种生活方式(表 2 )。博士后表示,在学术界取得成功所需的时间和承诺往往会影响研究人员的个人、职业和社会生活:

Table 2. Categories which emerged from the codes: Life in Academia.

表 2.从代码中出现的类别:学术界的生活。

| Category | Codes (modified) | Codes (modified) |

|---|---|---|

| Academic life | expectation to publish grantsmanship is necessary academic freedom is an incentive administrative obligations | “academia is not a meritocracy” opportunity to teach mentoring students |

| Challenges | hard work job market is competitive academic politics long hours lack of recognition for work | difficult relationships limited opportunities for advancement overworked burn out |

| Financial security | lack of financial stability underpaid | need for more funding |

| Understand the risk | “luck is needed for success” success is not guaranteed | assess cost-benefit ratio be ready for setbacks |

| Wellness | hard work | difficult relationships |

| Work-life balance | demanding workload familial obligations | parenthood |

…anyone who pursues a research career has to be [prepared to] work in a high-pressure environment that consumes your life. There is really no separation between your research and life. You must be prepared to sacrifice holidays and special occasions with your family. (379)

…任何从事研究事业的人都必须 [准备好] 在消耗你生命的高压环境中工作。你的研究和生活之间真的没有分离。您必须准备好牺牲与家人在一起的假期和特殊场合。(379)

So, the postdocs advise performing a self-assessment of your values and priorities to determine whether this career can satisfy your personal and professional needs:

因此,博士后建议对您的价值观和优先事项进行自我评估,以确定该职业是否能满足您的个人和专业需求:

Consider what balance of work and personal time is acceptable and will make you happy. Those who reliably and regularly receive high impact publications and large grants tend to spend a majority of their time in lab writing, and have less free time outside [of the] lab. (157)

考虑一下工作和个人时间的平衡是可以接受的,并且会让你开心。那些可靠且定期收到高影响力出版物和大额资助的人往往将大部分时间花在实验室写作上,而实验室外的空闲时间较少。(157)

Set the professional goals you are willing to achieve without endangering your personal life. (197)

设定您愿意在不危及个人生活的情况下实现的职业目标。(197)

Respondents describe the challenges they face as postdoctoral researchers to also include long hours, a demanding workload, unanticipated setbacks, a competitive funding and research climate, and delayed gratification, consistent with other studies [5]:

受访者描述了他们作为博士后研究人员面临的挑战,还包括长时间工作、苛刻的工作量、意想不到的挫折、竞争激烈的资金和研究氛围以及延迟满足,这与其他研究一致 [5]:

Academic research is great if you enjoy working hard, tolerate frustration, and accept that sometimes you need to work for years before seeing results. It’s not that great if making money is important for you, if you need a lot of free time for your non-work life, and if you need frequent reinforcement and sense of success. (17)

如果您喜欢努力工作,忍受挫折,并接受有时您需要工作多年才能看到结果,那么学术研究是很棒的。如果赚钱对你很重要,如果你的非工作生活需要大量的空闲时间,如果你需要频繁的强化和成功感,那就不是那么好了。(17)

The trade-offs to these challenges include scientific creativity, problem solving, academic freedom, and travel. Academic freedom was cited as one of the main benefits of pursuing an academic research career:

这些挑战的权衡包括科学创造力、解决问题、学术自由和旅行。学术自由被认为是从事学术研究事业的主要好处之一:

If making discoveries on a day to day basis, big or small, is what you crave for then [this] is the career. If you have the patience to go through failure or unexpected results to find something new and interpret it, be criticized without giving up and then prove your point then this [is] the career. If you are curious enough to get to the truth, no matter what but at your own pace then this is the career. (427)

如果每天都有发现,无论大小,是你渴望的,那么 [这就是] 你的职业。如果你有耐心经历失败或意想不到的结果,找到新的东西并解释它,接受批评而不放弃,然后证明你的观点,那么这就是 [这就是] 职业。如果你有足够的好奇心去了解真相,无论如何,但要按照你自己的节奏,那么这就是你的职业。(427)

Be prepared for a lot of freedom in thought and ability to pursue academic interests with a great deal of effort in lab management, grant writing, and grant management. (75)

准备好在思想上有很大的自由度,并有能力追求学术兴趣,并在实验室管理、资助申请写作和资助管理方面付出大量努力。(75)

Many also note that luck (or probability) plays a significant role in your success in experiments, publications, funding, and job opportunities. This perception has been previously linked to levels of outcome expectations among postdocs, i.e., whether their hard work leads to high performance [27]:

许多人还指出,运气(或概率)对您在实验、出版物、资金和工作机会方面的成功起着重要作用。这种看法以前与博士后对结果的期望水平有关,即他们的辛勤工作是否会导致高绩效 [27]:

You can put in 80 hours a week, but unless you get lucky, you will not be able to publish in multiple high impact journals in order to attain a position in Academia. The hyper competitive climate in science is extremely discouraging to intelligent and innovative minds… (951)

你可以每周投入 80 小时,但除非你运气好,否则你将无法在多个高影响力期刊上发表文章以在学术界获得职位。科学界的激烈竞争环境让聪明和创新的人非常沮丧…(951)

However, several caution against allowing your research success to define you:但是,有几个人警告不要让您的研究成功定义您:

Do not base your sense of self-worth on having an academic position. Give it your best shot, but there are many viable pathways out there and you shouldn’t feel that being an academic is the only viable option. (186)

不要将你的自我价值感建立在拥有学术地位上。尽你最大的努力,但有很多可行的途径,你不应该觉得成为一名学者是唯一可行的选择。(186)

Overall, the postdocs describe life in academia as one characterized by significant time demands for conducting research and fulfilling other responsibilities. They note the importance of establishing a healthy work-life balance and advise prospective researchers to determine whether their fields of interest can meet their personal and professional expectations.

总体而言,博士后将学术界的生活描述为进行研究和履行其他职责需要大量时间的生活。他们指出了建立健康的工作与生活平衡的重要性,并建议潜在的研究人员确定他们感兴趣的领域是否能够满足他们的个人和专业期望。

Postdocs feel underpaid and undervalued博士后感到薪酬过低和被低估

Several survey respondents indicate that compensation at the postdoctoral level is unsatisfactory:

一些调查受访者表示,博士后水平的薪酬并不令人满意:

Relative to their educational attainment and training, postdocs are very poorly paid, and there is little or no job security. (199)

相对于他们的教育程度和培训,博士后的薪水非常低,而且几乎没有工作保障。(199)

…academic institutions arbitrarily devalue your contributions both financially and through the game of non-promotion. (835)…

学术机构在财务上和通过不促销的游戏任意贬低您的贡献。(835)

Many call prospective candidates to be aware of these financial challenges:

许多人打电话给潜在的候选人,让他们意识到这些财务挑战:

Can you live with a salary of 20k-30k as a graduate student until you are 30? Are you ready to start a family with a salary of 50k as a postdoc when your friends are making 70k-80k without a PhD? (979)

研究生能拿着 20k-30k 的薪水生活到 30 岁吗?当你的朋友在没有博士学位的情况下赚 50k-70k 时,你准备好以 70k 的薪水组建一个家庭作为博士后了吗?(979)

However, the postdocs indicate that passion should be the primary motivation for those interested in pursuing an academic career, not financial gain:

然而,博士后表明,对于那些有兴趣追求学术事业的人来说,热情应该是主要动机,而不是经济利益:

If you care about money, don’t come. This field is sustained only by passion now. (448)

如果你在乎钱,就不要来。这个领域现在只能靠激情来维持。(448)

Science should be your number one passion. It must be strong enough to overlook the many long hours and the fact that you’re spending your peak earning potential years in a stressful, low-pay, unstable ’training’ position. (736)

科学应该是您的第一爱好。它必须足够强大,以忽略许多长时间的工作以及您在压力大、低薪、不稳定的“培训”职位上度过收入高峰期的事实。(736)

Though several postdocs feel many institutions fail to provide the level of professional development, career placement, and employee benefits to postdocs as given to students or faculty [39, 40]. These limited job prospects lead to feelings of not being appreciated in postdoc positions [41]:

尽管一些博士后认为许多机构未能为博士后提供与学生或教职员工相同的专业发展、职业安置和员工福利水平 [39,40]。这些有限的工作前景导致在博士后职位上不被欣赏的感觉 [41]:

You will be mentally run-down, under-paid, under-appreciated, and in the end make less than you’re worth with fewer benefits. (732)

你会精神疲惫、工资过低、不被赏识,最终赚得不到你的价值,好处也更少。(732)

I don’t want my kids to go into research; I want them to do something where their work and knowledge is actually appreciated. And where this appreciation is reflected in the salary. (693)

我不想让我的孩子们去做研究;我希望他们做一些让他们的工作和知识真正得到赞赏的事情。而这种升值反映在薪水中。(693)

So, many highly recommend being proactive about choosing the best work environment to complete your postdoctoral training:

因此,许多人强烈建议积极主动地选择最佳工作环境来完成您的博士后培训:

…environment matters. Being at a supportive institution with excellent mentorship and opportunities in your field of choice will be important for success. (777)…

环境很重要。在您选择的领域拥有出色指导和机会的支持机构对于成功非常重要。(777)

Have a strong mentor and support system at your institution because your institutional resources will be heavily counted toward successfully obtaining a grant. (367)

在您的机构中拥有强大的导师和支持系统,因为您的机构资源将在很大程度上用于成功获得资助。(367)

Make sure to choose a lab that publishes regularly and a mentor who will actually act as a mentor and not just get science out of you. (594)

确保选择一个定期发布的实验室和一位真正充当导师的导师,而不仅仅是从你那里获得科学知识。(594)

The postdoctoral researchers find that the state of funding in academia has made it difficult to not only support their research but also their personal cost of living. However, they find that if you are passionate about your work and can find a supportive institution with strong mentorship, those sacrifices can be reduced and are ultimately worth the effort.

博士后研究人员发现,学术界的资金状况不仅难以支持他们的研究,而且难以支持他们的个人生活成本。然而,他们发现,如果你对自己的工作充满热情,并能找到一个有强大指导的支持机构,这些牺牲就可以减少,最终是值得的。

Strategies for Success 成功策略

Prepare for multiple career paths为多条职业道路做好准备

Some postdocs do not recommend pursuing an academic research career at this time. Despite hard work and considerable sacrifice, the probability of obtaining a tenure-track faculty position and financial insecurity were cited as the main deterrents for pursuing an academic research career:

一些博士后不建议此时从事学术研究事业。尽管努力工作和相当大的牺牲,但获得终身教职的可能性和经济上的不安全被认为是追求学术研究生涯的主要障碍:

Do something else. I am a successful young research scientist, but I would not advise a student to pursue a career in academic research. The balance between the effort put in, and the benefits gained is completely skewed. Dedication and hard work are no guarantee of success in terms [of] publications. Very often, early career decisions as to the lab you apply to, to do your PhD training, have an inordinate influence in your career. Also, mentors have an inordinate influence in their [students’] happiness and success… (199)

做点别的事。我是一名成功的年轻研究科学家,但我不建议学生从事学术研究。付出的努力和获得的好处之间的平衡是完全不平衡的。就出版物而言,奉献和努力工作并不能保证成功。很多时候,关于你申请的实验室进行博士培训的早期职业决定,会对你的职业生涯产生过大的影响。此外,导师对他们 [学生] 的幸福和成功有着过大的影响…(199)

I just started to apply for tenure-track openings and have been told by dept. chairs that I need to have funding (K-award) in hand to be seriously considered for a position. I have 30+ publications and received my own funding since I was a graduate student (NIH F31 & F32 plus over $120K in supplemental funding). My K-award is currently under revision and feel my future is currently 100% dependent on my whether I get a K regardless of what is on my CV or my past accomplishments. (238)

我刚刚开始申请终身教职职位空缺,系主任告诉我,我需要有资金(K-award)才能被认真考虑担任某个职位。我有30+出版物,自从我还是研究生以来就获得了自己的资助(NIH F31和F32加上超过12万美元的补充资金)。我的 K-award 目前正在修订中,我觉得我的未来目前 100% 取决于我是否获得 K,无论我的简历上或我过去的成就如何。(238)

In consideration of these challenges, several postdocs indicate that there are many other viable career opportunities for researchers. They also suggest that academic research careers should be framed as a part of a myriad of successful post-PhD careers, rather than an alternative to those unsuccessful at achieving a faculty position:

考虑到这些挑战,一些博士后表示,研究人员还有许多其他可行的职业机会。他们还建议,学术研究事业应该被定义为无数成功的博士后职业的一部分,而不是那些未能成功获得教职的人的替代品:

Please, don’t consider [an academic research career] as the only respectable career for a scientist. Keep your options open. (474)

请不要将 [学术研究事业] 视为科学家唯一值得尊敬的职业。保持您的选择开放。(474)

I think the PhD is still a worthy goal. But I’ve come to realize the faculty position isn’t the be all and end all of the process. There are many other useful and creative and important ways to use a [PhD] degree. I think new generations are coming around to that: they embrace alternative careers and they are being trained for them in better ways as universities accept the fact that most of us don’t attain the faculty job… Another thing is, if you get the [PhD] and you want to leave academia, make a plan for that career- don’t get sucked into a postdoc when you [don’t] want to become a PI. (390)

我认为博士学位仍然是一个值得的目标。但我开始意识到,教职职位并不是整个过程的全部和结束。还有许多其他有用、有创意和重要的方法来使用 [PhD] 学位。我认为新一代正在接受这一点:他们接受其他职业,并且随着大学接受我们大多数人没有获得教职的事实,他们正在以更好的方式接受培训…另一件事是,如果你拿到了 [博士学位] 并且想离开学术界,就为这个职业制定一个计划——当你 [不想] 成为一名 PI 时,不要被吸引到博士后中。(390)

If you can succeed in basic research, you can be more successful in industrial, financial or other [fields]. (446)

如果你能在基础研究方面取得成功,你就可以在工业、金融或其他 [领域] 取得更大的成功。(446)

Some of the postdocs recommend exploring multiple career options immediately, while others encourage keeping an open mind about multiple career paths in case the academic track becomes less viable (Table 3). Pursuing a career in industry was the most cited career choice outside of academia by the postdoc respondents because of its competitive salaries, structured career advancement, better work-life balance, and the opportunity to continue scientific research or make contributions in other capacities.

一些博士后建议立即探索多种职业选择,而另一些博士后则鼓励对多种职业道路保持开放态度,以防学术轨道变得不可行(表 3)。从事工业事业是博士后受访者在学术界之外引用最多的职业选择,因为它具有有竞争力的薪水、结构化的职业发展、更好的工作与生活平衡以及继续科学研究或以其他身份做出贡献的机会。

Table 3. Categories which emerged from the codes: Career planning.表 3.从代码中出现的类别:职业规划。

| Category | Codes (modified) | Codes (modified) |

|---|---|---|

| Career planning | thoroughly evaluate career landscape before committing carefully assess laboratory environment before committing have a backup plan be realistic about expectations be open-minded talk to people at various stages of career | gain research exposure early conduct informational interviews consider location find your research niche revise career plan regularly evaluate whether PhD is necessary |

| Non-academic careers | explore all career options industry translational research finance non-bench careers medical school science policy | Master of Business Administration (MBA) government entrepreneurship* patent law* consulting* science communication* science and medical writing* |

| Commitment | long-term commitment requires sacrifice persevere through failure and rejection enjoy the journey be open to different research areas | long-term gratification be open to developing new skills take advantage of opportunities don’t remain on career track if odds are not favorable |

| Self-reflection | know your values establish projected time frame consider which aspects of research you like explore your skills and abilities | know your limitations evaluate strengths and weaknesses imposter syndrome |

| Negative sentiments toward academia | “don’t go into academia” “academia is a broken system” | “boycott field” |

added by authors to present a comprehensive view of non-academic careers.

由作者添加,以呈现非学术职业的全面视图。

Reflect on your motivation 反思你的动机

Passion, coupled with resilience, was cited as the primary driving force for pursuing an academic research career:

热情加上韧性被认为是追求学术研究生事业的主要驱动力:

Be sure you are passionate about your field of [study] and are pursuing the career for the right reasons, because it is not an easy career path. It allows for creativity, flexibility, and joys of learning and discovery, but is challenging in terms of funding, navigating bureaucracy and politics, administrative obligations, etc. (101)

确保您对自己的 [学习] 领域充满热情,并且出于正确的原因追求这份职业,因为这不是一条轻松的职业道路。它允许创造力、灵活性以及学习和发现的乐趣,但在资金、驾驭官僚主义和政治、行政义务等方面具有挑战性(101)

The postdocs assert that researchers should not be driven by extrinsic factors such as wealth or fame:

博士后断言,研究人员不应该被财富或名声等外在因素所驱动:

People that are successful in the academic field are not in it for the money or fame. Chances are you won’t become famous or rich, but you do have the potential to help countless amounts of people, and if you are passionate about research and helping others, you shouldn’t let the troubles of funding or the woes of others deter you from your goals. (415)

在学术领域取得成功的人不是为了金钱或名声。你可能不会出名或富有,但你确实有可能帮助无数人,如果你热衷于研究和帮助他人,你不应该让资金的麻烦或他人的困境阻止你实现你的目标。(415)

Never forget that the goal of biomedical research is to eventually find targets for human health issues that will hopefully help eradicate disease… and that research does not occur in a vacuum and requires passion, leadership, hard-work, and collaboration. (635)

永远不要忘记,生物医学研究的目标是最终找到人类健康问题的目标,希望有助于根除疾病…而且研究不是在真空中进行的,需要激情、领导力、努力工作和协作。(635)

Many of the respondents described the absence of passion as one of the leading causes for abandoning the pursuit of an academic research career. They maintain that love for the sciences and the impact of academic research is what makes the sacrifices worthwhile.

许多受访者将缺乏激情描述为放弃追求学术研究事业的主要原因之一。他们坚持认为,对科学和学术研究影响的热爱使牺牲变得值得。

Assess readiness 评估就绪情况

To supplement this advice, the postdocs define the qualities of a good scientist:为了补充这一建议,博士后定义了优秀科学家的品质:

…true scientists care very little about money or taking the easy route. They are just intellectually curious and looking for answers to their questions. (77)…

真正的科学家很少关心金钱或走捷径。他们只是在智力上充满好奇心,并寻找问题的答案。(77)

Make sure you really enjoy coming up with your own hypotheses, have the knowledge to assess their novelty, and the writing skills to get them funded. (613)

确保您真的喜欢提出自己的假设,拥有评估其新颖性的知识,以及获得资金的写作技巧。(613)

[Researchers’] daily tasks rely on numerous skills like writing communication, teamwork, problem solving, planning, learning, self-criticism, etc. (730)

[研究人员的] 日常任务依赖于许多技能,如写作、沟通、团队合作、解决问题、计划、学习、自我批评等(730)

According to the respondents, good scientists are passionate researchers who conduct thorough scientific investigations, demonstrate resilience in the face of difficulty, and are disciplined leaders in their fields. They are confident, excellent collaborators, and comfortable with failure and uncertainty. Their ability to take criticism and recover from setbacks allows them to overcome rejection and persevere through the many challenges present on this track:

根据受访者的说法,优秀的科学家是充满激情的研究人员,他们进行彻底的科学调查,在面对困难时表现出韧性,并且是各自领域纪律严明的领导者。他们自信、优秀的合作者,对失败和不确定性感到满意。他们接受批评并从挫折中恢复过来的能力使他们能够克服拒绝并坚持不懈地应对这条赛道上出现的许多挑战:

Doing good science is slow and hard, and there are many times in research that it is easy to get discouraged—make sure you identify a way to reignite your passion for research so that you can overcome those times of frustration—we need more people and more diverse ideas in this profession, not fewer. (210)

做好科学研究是缓慢而困难的,在研究中很多时候很容易气馁——确保你找到一种方法来重新点燃你对研究的热情,这样你就可以克服那些挫折的时候——我们需要更多的人和更多样化的想法在这个行业,而不是更少。(210)

Based on these qualities, the postdocs call prospective researchers to assess their strengths and weaknesses to determine if they are well-suited for this profession:

基于这些品质,博士后打电话给潜在的研究人员,评估他们的长处和短处,以确定他们是否适合这个职业:

Do you truly enjoy research and the responsibilities (i.e. writing papers/grants) that come with those responsibilities? Are you competitive and confident in your ability to do science? Are you able to compartmentalize when research fails and not place blame on yourself? (206)

您真的喜欢研究和随之而来的责任(即撰写论文/资助)吗?您是否有竞争力并对自己的科学能力充满信心?当研究失败时,您能够划分界限而不将责任归咎于自己吗?(206)

There is always someone smarter out there, but you can control how hard you work. Research, like many things in life, is a battle of attrition. Work hard in the lab, write a lot… .like more than you think you should, read often, collaborate with others, keep growing. And most importantly, don’t let a paper or grant rejection define you. Your worth is derived from the things in your control, not the things out of your control. (798)

总有人更聪明,但你可以控制你工作的辛苦程度。就像生活中的许多事情一样,研究是一场消耗战。在实验室努力工作,写很多… .喜欢比你想象的更多,经常阅读,与他人合作,不断成长。最重要的是,不要让论文或资助被拒绝来定义你。你的价值来自于你控制的事情,而不是你无法控制的事物。(798)

The postdocs recommend performing an honest self-assessment of your motivations and abilities to determine whether you have the drive and character necessary to maximize your chances at successfully obtaining a tenure-track faculty position.

博士后建议对您的动机和能力进行诚实的自我评估,以确定您是否具有必要的动力和性格,以最大限度地提高成功获得终身教职的机会。

Be strategic 具有战略意义

The postdocs emphasize the importance of being diligent and methodical about career development:

博士后强调勤奋和有条不紊地对待职业发展的重要性:

Pursuing science for the sake of exploring how the world around us works, and planning an academic research career are two very different endeavors, which require many mutually exclusive skills. Working towards a career in science must include careful choice of mentors, labs and projects in graduate school and post-doc. (714)

为了探索我们周围世界的运作方式而追求科学,与规划学术研究事业是两种截然不同的努力,需要许多相互排斥的技能。努力从事科学事业必须包括仔细选择研究生院和博士后导师、实验室和项目。(714)

They also advise strengthening your research skills, staying informed about current research, and finding a supportive community to grow and develop in:

他们还建议加强您的研究技能,随时了解当前的研究,并找到一个支持性的社区来成长和发展:

Learn how to critically read data and develop independent ideas and experiments. Work hard both at the bench and at understanding and staying current in the literature. Learn to ask for help and take criticism. Build your professional network to include [scientists] of various backgrounds and expertise. Meet and discuss your science as [frequently] as possible with these colleagues. (568)

了解如何批判性地读取数据并开发独立的想法和实验。在工作台上努力工作,理解和保持最新的文献。学会寻求帮助和接受批评。建立您的专业网络,包括具有不同背景和专业知识的 [科学家]。尽可能 [经常] 与这些同事会面并讨论您的科学。(568)

The following sections expand on these strategies for success (Table 4).

以下各节扩展了这些成功策略( 表 4 )。

Table 4. Categories which emerged from the codes: Strategies for Success.

表 4.从代码中出现的类别:成功策略。

| Category | Codes (modified) | Codes (modified) |

|---|---|---|

| Passion | “field is sustained only by passion” “if this is your dream, the sacrifices are worth it” | money (wealth) should not be primary motivation |

| Qualities of a good scientist | patient confident open-minded resilient creative and innovative | intellectually curious “thick-skinned” disciplined strong leader has integrity |

| Research skills | strengthen research skills strengthen writing skills | “commit to doing good science” |

| Strategy | be strategic about decisions be comfortable with uncertainty explore current literature attend seminars be competitive be prepared to self-learn choose the right graduate school focus on the positives | be vigilant about opportunities have a holistic approach to advancement give presentations start simple have multiple projects choose a field in demand have specific research focus utilize your advantages |

| Laboratory | choose the right laboratory find a well-established PI | choose a famous laboratory evaluate laboratory publication record |

| Mentorship | seek strong mentorship evaluate mentorship compatibility | learn to ask for help |

| Publications | “publications are the currency of research” publish in high impact journals | don’t need to publish in top journals |

| Network | seek collaborations find supportive community | build connections develop communication skills |

| Transferable skills | understand skills valued outside of academia seek cross-training in areas beyond research focus | develop skills for non-bench careers pursue managerial training |

Choose the right laboratory 选择合适的实验室

The postdocs stress that your choice of laboratory is one of the most critical steps for career advancement:

博士后强调,您选择的实验室是职业发展最关键的步骤之一:

Find a lab that has [a] track record of postdocs transitioning to professorships. Your postdoc boss has the most influence on your own independent academic career. [It’s] all about mentorship. (279)

找到一个有博士后转为教授职位记录的实验室。你的博士后老板对你自己的独立学术生涯影响最大。[这] 一切都与指导有关。(279)

Do intensive research, not only about the area you’re interested in, but the environment/morale of the lab itself before taking a job in a lab. (175)

在实验室工作之前,不仅要深入研究你感兴趣的领域,还要研究实验室本身的环境/士气。(175)

The postdocs recommend carefully assessing all aspects of the laboratory environment before committing to a mentor or laboratory. This might involve conducting informational interviews to gain insight into your potential work environment, the laboratory’s publication record, and your prospective PI’s expectations of you. Due to your PI’s influence on your future, many advise assessing mentorship compatibility before committing to a laboratory to ensure that your values and expectations are compatible.

博士后建议在委托导师或实验室之前仔细评估实验室环境的各个方面。这可能涉及进行信息访谈,以深入了解您的潜在工作环境、实验室的出版记录以及您的潜在 PI 对您的期望。由于您的 PI 对您的未来有影响,许多人建议在承诺进入实验室之前评估导师制的兼容性,以确保您的价值观和期望是兼容的。

Choose mentors wisely 明智地选择导师

The postdocs strongly emphasize the importance of strong mentorship on career growth:

博士后强烈强调强有力的指导对职业发展的重要性:

Find a mentor who has the time and passion to see [you] grow and is willing to explain what the different career trajectories are, how you go about finding them, and wants to assist you in that journey. You need to find a mentor who values your potential as a future scientist and doesn’t just view you as cheap labor. (282)

找一位有时间和热情看到 [你] 成长并愿意解释不同的职业轨迹是什么,你如何找到它们,并希望在这段旅程中帮助你的导师。您需要找到一位重视您作为未来科学家的潜力,而不仅仅是将您视为廉价劳动力的导师。(282)

The greatest component to my success thus far has been asking the right people for help with grants, experiments, and other challenges. Without the support of my community it would be difficult to push forward research initiatives and secure funding for them. (31)

到目前为止,我成功的最大组成部分是向合适的人寻求资助、实验和其他挑战的帮助。如果没有我所在社区的支持,将很难推进研究计划并为其获得资金。(31)

The postdocs share that insufficient support from PIs may leave researchers underdeveloped in some critical academic skills. So, they highly recommend seeking out multiple mentors at various stages of their careers because these professionals offer invaluable perspectives, skill sets, advice, and resources.

博士后分享说,PI 的支持不足可能会使研究人员在某些关键的学术技能方面发展不足。因此,他们强烈建议在职业生涯的不同阶段寻找多位导师,因为这些专业人士提供了宝贵的观点、技能、建议和资源。

Publication strategies to consider要考虑的出版策略

Although there is debate about the significance of journal impact factor, there is certainty among the postdocs about the need for publications to become established in the academic community:

尽管对期刊影响因子的重要性存在争议,但博士后可以肯定地认为,出版物需要在学术界站稳脚跟:

[Academia is] not a meritocracy. Either you have to publish a lot, or publish in high impact journals only. (515)

[学术界] 不是一个精英统治。要么你必须发表大量文章,要么只在高影响力期刊上发表文章。(515)

Papers are the currency of research, so it is crucial to publish extensively in reputed journals. In the job market, being able to market your ’brand’ of science—topics, approach, methods, [etc.] becomes an important ingredient to success. (714)

论文是研究的货币,因此在知名期刊上广泛发表文章至关重要。在就业市场上,能够推销您的科学“品牌”——主题、方法、方法 [等] 成为成功的重要因素。(714)

Many recommend strengthening your research and writing skills to maximize grant and publication success:

许多人建议加强您的研究和写作技能,以最大限度地提高资助和出版成功率:

Develop your brainstorming/project design skills. The opportunities to do that as a postdoc may be slim, but it is essential to being able to write your own grants and secure independent funding. (172)

培养您的头脑风暴/项目设计技能。作为博士后,这样做的机会可能很渺茫,但对于能够撰写自己的资助申请并获得独立资金至关重要。(172)

I would recommend that they try to be as independent as they can in their research ideas, strategies and grant writing (from Grad school and on). If they are successful at each of these, and their ideas are well perceived by their field, then they likely have a shot. It is important to think about what you bring to the field and what you want to teach others through your research and mentoring. (405)

我建议他们在研究思路、策略和资助申请写作(从研究生院开始)中尽可能独立。如果他们在每一项工作上都取得了成功,并且他们的想法在他们的领域得到了很好的理解,那么他们很可能有机会。重要的是要考虑你为该领域带来了什么,以及你想通过研究和指导教给别人什么。(405)

They also advise assessing the publication record of the laboratory you are considering before committing to it:

他们还建议在承诺之前评估您正在考虑的实验室的出版记录:

For grad school and postdoc [choose] labs where the PI is established in his field because this is the way to get published in high ranking journals and to get your grants approved, without which you cannot develop a long-lasting career in Academia. (312)

对于研究生院和博士后 [选择] PI 在其领域建立的实验室,因为这是在高级期刊上发表文章并获得资助批准的方式,没有它,你就无法在学术界发展持久的职业生涯。(312)

Get the training from the lab [with a] history of publishing top journals. Name of the school is not as important as the quality of the paper your candidate lab publishes. (330)

从实验室获得培训 [具有] 发表顶级期刊的历史。学校名称不如候选实验室发表的论文质量重要。(330)

Some suggest working on various projects to enhance your academic record:有些人建议从事各种项目以提高您的学习成绩:

…do not only work on one project, but several, if you work on a risky project, get a second safer project to ensure you get regular publications… (25)…

不仅要做一个项目,还要做几个,如果你做一个有风险的项目,就买第二个更安全的项目,以确保你得到定期的出版物…(25)

Having a diverse portfolio helps, rather than one big project, one big book, or one big paper in the pipeline. I built my pipeline very slowly, and that gave me stress. I do think there is a need to step outside the publish or perish game, and craft one’s own rules of engagement if possible. One way to do this is possibly doing work meaningful to oneself rather than looking at where the funding comes from, or what everyone else is doing. (891)

拥有多元化的作品集会有所帮助,而不是一个大项目、一本大书或一篇大论文正在筹备中。我建立我的管道非常缓慢,这给我带来了压力。我确实认为有必要跳出 Publish or Perish 的游戏,如果可能的话,制定自己的参与规则。做到这一点的一种方法可能是做对自己有意义的工作,而不是查看资金来自哪里,或者其他人在做什么。(891)

The postdocs highlight the importance of publishing because it gives your research exposure, builds your credibility within the scientific community, and increases your competitiveness for an academic research position.

博士后强调了发表的重要性,因为它可以提高您的研究曝光率,在科学界建立您的信誉,并提高您获得学术研究职位的竞争力。

Network 网络

The postdocs find networking to be an essential component of success in academia:

博士后发现人际网络是学术界成功的重要组成部分:

[Networking] with peers and labs you’re interested in and offering your help or services or forming collaborations provides vital long-lasting and fruitful connections. [It’s] often who you know that counts in terms of publications. [Get] involved with excellent research labs, learn from them and become a vital part of the team. (518)

与您感兴趣的同行和实验室 [建立联系] 并提供帮助或服务或建立合作,可提供重要、持久和富有成效的联系。就出版物而言,你认识的人往往很重要。[参与] 优秀的研究实验室,向他们学习并成为团队的重要组成部分。(518)

Go outside your comfort zone of the lab, engage in science outreach, network, interact! Science is more than working hard at the bench, and I wish somebody had told me that earlier in my career. (685)

走出实验室的舒适区,参与科学推广、交流、互动!科学不仅仅是在工作台上努力工作,我希望在我职业生涯的早期有人告诉我这一点。(685)

The postdocs recommend attending conferences, building connections, and collaborating with others because those are important ways to develop relationships with scientists throughout the community, learn from their expertise, find mentors, and share your own research and ideas.

博士后建议参加会议、建立联系和与他人合作,因为这些是与整个社区的科学家建立关系、学习他们的专业知识、寻找导师以及分享您自己的研究和想法的重要方式。

Overall, the postdocs’ provided these recommendations to help prospective researchers make more informed decisions about their research career pursuits:

总体而言,博士后提供了这些建议,以帮助潜在的研究人员对他们的研究生涯追求做出更明智的决定:

In order to achieve a successful career in academic research, one needs to understand early enough that it is more than a job in science—it a permanent dedication to scientific topics, with a lot of workload for a single person. Persistence and patience are essential traits to succeed. (469)

为了在学术研究中取得成功,人们需要尽早明白,这不仅仅是一份科学工作——它是永久致力于科学主题的,一个人需要承担大量的工作量。坚持和耐心是成功的基本品质。(469)

Discussion 讨论

In this manuscript, we present the advice of 994 postdocs on pursuing an academic research career. The postdocs’ responses were analyzed to derive codes that encapsulated the major concepts being discussed. We found 177 distinct codes in 20 categories across 10 subthemes and two broad themes. In the first theme, Life in Academia, postdocs detail a picture of academic life from the point of view of the trainee, not often captured in the literature. According to several studies, the postdoctoral experience in the United States has not been captured comprehensively in more than a decade [7, 22]. This scarcity of data negatively impacts postdoc career outcomes and the overall vitality of the scientific workforce.

在这份手稿中,我们提出了 994 名博士后关于从事学术研究事业的建议。对博士后的回答进行了分析,以得出封装所讨论的主要概念的代码。我们发现了 10 个子主题和 2 大主题的 20 个类别的 177 个不同的代码。在第一个主题 Life in Academia 中,博士后从受训者的角度详细介绍了学术生活的画面,这在文献中并不常见。根据几项研究,十多年来,美国的博士后经历并没有得到全面反映 [7,22]。这种数据的稀缺性对博士后职业成果和科学工作者的整体活力产生了负面影响。

In this study, postdocs highlight both the flexibility and challenges of academic life: “It allows for creativity, flexibility, and joys of learning and discovery, but is challenging in terms of funding, navigating bureaucracy and politics, administrative obligations, etc.” They also report that this track demands a significant commitment to seeking funding and publishing research, typically exceeding normal work hours. Thus, for many postdocs becoming a faculty member would fulfill their passion for research and discovery, but success requires managing the constant tension between work demands and their personal lives. Before committing to this career path, one has to decide if the lifestyle and its challenges are worth the reward.

在这项研究中,博士后强调了学术生活的灵活性和挑战:“它允许创造力、灵活性以及学习和发现的乐趣,但在资金、驾驭官僚主义和政治、行政义务等方面具有挑战性。他们还报告说,这个轨道需要对寻求资金和发表研究做出重大承诺,通常超过正常工作时间。因此,对于许多博士后来说,成为一名教职员工将满足他们对研究和发现的热情,但成功需要管理工作需求和个人生活之间的持续紧张关系。在致力于这条职业道路之前,人们必须决定这种生活方式及其挑战是否值得回报。

One major challenge that the postdocs frequently referenced in this study was financial insecurity. We suspect that not everyone considers the financial impact of years of training until they are immersed in it. In this study, we find postdocs’ frustrations over aspects of financial support. Some postdocs advised not pursuing this path unless you come from a wealthy family. Others were very specific about the personal cost of this education and training: “…I’m in my mid 30’s and have worked 60+ hours a week for 10+ years for essentially minimum wage in hopes of getting an academic position.” Such openness is needed to help future trainees have a clearer understanding of the challenges in the field and help funding agencies understand how to improve access for all trainees. Choosing to pursue an academic career should not be dependent upon how long one can sacrifice financial stability and security. Postdocs should not be driven away from academic paths because they do not have the financial means to complete a postdoc.

博士后在这项研究中经常提到的一个主要挑战是财务不安全。我们怀疑并不是每个人都会考虑多年培训的财务影响,直到他们沉浸其中。在这项研究中,我们发现博士后对经济支持方面的挫败感。一些博士后建议除非你来自富裕家庭,否则不要走这条路。其他人对这种教育和培训的个人成本非常具体:“…我 30 多岁了,每周工作 60+ 小时,持续 10+ 年,基本上是最低工资,希望能得到一个学术职位。需要这种开放性来帮助未来的学员更清楚地了解该领域的挑战,并帮助资助机构了解如何改善所有学员的入学机会。选择从事学术事业不应取决于一个人可以牺牲财务稳定和安全多长时间。博士后不应该因为没有经济能力来完成博士后而被迫离开学术道路。

The increasing length of this poorly funded training period with no guarantee of success causes financial instability and job insecurity [22]. Moreover, the increasing age for establishing scientific independence also translates into why there is a limited availability of faculty positions. Zimmerman shares that the reported average age for scientists to secure their first NIH grant is 42 [7]. This data along with the fact that the number of tenure-track faculty positions has remained consistent over the past few decades may in part account for the shortage of available positions as more senior researchers maintain their tenure to reap the benefits of the personal, professional, and financial challenges they have endured [7, 21].

这种资金不足且无法保证成功的培训期越来越长,导致财务不稳定和工作不稳定 [22]。此外,建立科学独立的年龄不断提高也解释了为什么教师职位的可用性有限。Zimmerman 分享说,据报道,科学家获得第一个 NIH 资助的平均年龄为 42 岁 [7]。这些数据以及过去几十年来终身教职职位数量保持一致的事实,可能部分解释了可用职位的短缺,因为越来越多的高级研究人员保持他们的终身教职,以从他们所经历的个人、专业和财务挑战中获益 [7,21]。

In our second theme, Strategies for Success, postdocs provide recommendations for maximizing the potential for success in achieving an academic research career. The postdocs overwhelmingly emphasize the importance of possessing a strong love and passion for science. The current literature does not capture this emphasis on passion for success. ‘Passion’ being the most frequently cited code in this paper, referenced 189 times, highlights the weight of intrinsic values in the supposed impersonal scientific world. As previously mentioned, one respondent shared that “this field is sustained only by passion now.” For many, passion is absolutely key for longevity in the field. A unique category that emerged under this theme of passion was characterized by a caution in letting happiness or self-worth depend on scientific research or obtaining an academic position. One postdoc noted: “Don’t make your happiness depend on your academic research career.” Similarly, another noted: “Do not base your sense of self-worth on having an academic position.”

在我们的第二个主题 Strategies for Success 中,博士后提供了建议,以最大限度地发挥实现学术研究生涯的成功潜力。博士后压倒性地强调对科学拥有强烈的热爱和热情的重要性。目前的文献没有捕捉到这种对成功的热情的强调。“激情”是本文中引用次数最多的代码,被引用了 189 次,凸显了内在价值在所谓的非个人科学世界中的重要性。如前所述,一位受访者分享道:“这个领域现在只能靠激情来维持。对许多人来说,热情绝对是该领域长寿的关键。在这个激情主题下出现的一个独特类别的特点是谨慎地让幸福或自我价值取决于科学研究或获得学术职位。一位博士后指出:“不要让你的快乐取决于你的学术研究生涯。“同样,另一位用户指出:”不要将你的自我价值感建立在拥有学术地位的基础上。

Under our second major theme, the postdocs also expressed frustration about several other aspects of the field. A portion of them adamantly discouraged pursuing academia. Their responses confirm previous reports showing that the current state of academia is underscored by hypercompetitive climates, poor sense of financial security, and a perceived shrink in available tenure-track faculty positions [22, 25, 42]. One postdoc stated, “Put it this way, even if you are in a top Ivy League school you still need a mentor who will fight for you (I see my supervisor who is an MD/PhD every 4 weeks or so, left to troubleshoot alone), a lab that is well published in your field of study, multiple other postdocs all working in a synergistic way and all the while accepting you live on a ’maybe’ with regards to your future and getting paid poorly for it.” The perception of most disgruntled postdocs is this: the chances of securing a tenure-track faculty position are slim, even with tremendous passion and sacrifice, largely attributed to conditions that cannot be controlled. Many feel their hard work does not in fact pay off. The alternative perspective, and advice that we summarized from non-disgruntled postdocs: “I understand the chances of obtaining a faculty position and the challenges that come with it. However, I have a passion for this path, and I want to try to achieve it anyway, with the understanding that I will explore alternative career paths if this one does not prove successful.” We find this latter frame of mind, coupled with a framework where academic careers are one of many (not better or worse) successful career options for postdoctoral scholars, key for researchers in training.

在我们的第二个主要主题下,博士后也对该领域的其他几个方面表示失望。他们中的一些人坚决不鼓励追求学术界。他们的回答证实了以前的报告,该报告表明,学术界的现状突出表现为竞争激烈的环境、糟糕的财务安全感以及可用的终身教职职位的明显萎缩 [22,25,42]。一位博士后说:“这么说吧,即使你在一所顶尖的常春藤盟校,你仍然需要一个会为你而战的导师(我每 4 周左右就会见到我的导师,他是 MD/PhD,独自排除故障),一个在你的研究领域发表过很多文章的实验室,其他多个博士后都以协同方式工作,同时接受你生活在关于你的未来’可能’上,并且为此得到的报酬很低。大多数心怀不满的博士后的看法是:即使有巨大的热情和牺牲,获得终身教职的机会也很渺茫,这在很大程度上归因于无法控制的条件。许多人认为他们的辛勤工作实际上没有得到回报。我们从不满的博士后那里总结了另一种观点和建议:“我了解获得教职的机会以及随之而来的挑战。然而,我对这条道路充满热情,无论如何我都想尝试实现它,并明白如果这条道路不成功,我将探索其他职业道路。我们发现后一种心态,再加上一个框架,其中学术职业是博士后学者众多(没有更好或更坏)成功的职业选择之一,对于接受培训的研究人员来说至关重要。

While we did not ask the postdoc mentors about their trainee attitudes, a recent publication by seven institutions that hold Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training (BEST) programs report the results of faculty surveys of their BEST mentors to understand faculty perceptions around career development for their trainees [43]. The faculty believed that there was a shortage of tenure-track positions and felt a sense of urgency in introducing broad career activities for their trainees [43]. However, many do not feel they have the knowledge and resources necessary to guide and support the 85% of trainees who need professional development for careers outside of academia [22, 41]. The study also found that faculty perceived trainees themselves as lacking in the knowledge base of skills that are of interest to non-academic employers. For budding scientists along the training continuum, the advice given by postdocs in this manuscript could help enhance the knowledge base to best prepare them for non-academic career tracks.

虽然我们没有询问博士后导师的实习生态度,但七家举办拓宽科学培训经验(BEST)计划的机构最近发布的一份出版物报告了教师对其 BEST 导师的调查结果,以了解教师对实习生职业发展的看法 [43]。教职员工认为终身教职职位短缺,并感到迫切需要为他们的学员引入广泛的职业活动 [43]。然而,许多人认为他们不具备必要的知识和资源来指导和支持 85% 的受训者,这些受训者需要在学术界以外的职业中得到专业发展 [22,41]。该研究还发现,教师认为受训者本身缺乏非学术雇主感兴趣的技能知识基础。对于正在接受培训的崭露头角的科学家,博士后在本手稿中给出的建议可以帮助增强知识库,为他们进入非学术职业道路做好充分准备。

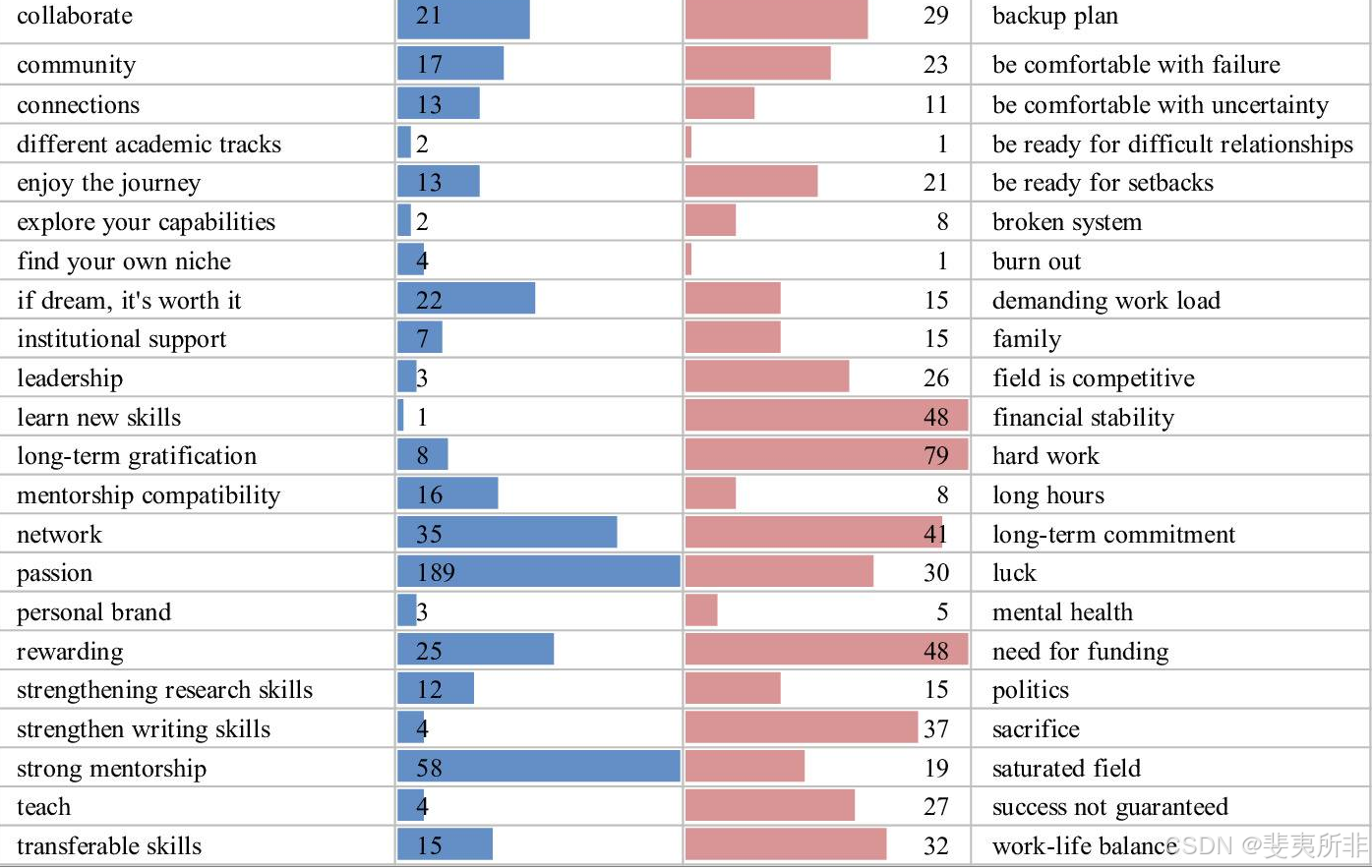

To better illustrate the cost-benefit ratio of pursuing an academic research career, we separated codes into either a benefits or costs category and indicated the frequency of references (Fig 2). Codes that were more associated with the benefits of pursuing an academic research career included academic freedom, strong mentorship, network, and passion, whereas administrative obligations, backup plan, financial stability, and hard work were associated with the costs. While the frequency of codes associated with the costs outnumbered the benefits, 546 to 489, sacrifices (or costs) and benefits are weighed differently between postdoc respondents.

为了更好地说明从事学术研究事业的成本效益比,我们将代码分为收益或成本类别,并指出了引用的频率(图 2)。与追求学术研究事业的好处更相关的代码包括学术自由、强大的指导、网络和热情,而行政义务、备用计划、财务稳定性和辛勤工作则与成本相关。虽然与成本相关的代码频率超过收益(546 比 489),但博士后受访者对牺牲(或成本)和收益的权衡不同。

Fig 2. Cost-benefit ratio of pursuing an academic research career.

图 2.追求学术研究事业的成本效益比。

The codes are listed alphabetically in their respective columns. An end limit of “45” (a double of the average frequency value of 22.5) was set for the data bars to provide a representative visual comparison of the codes’ frequencies.

代码按字母顺序列在各自的列中。为数据条设置了“45”的结束限制(平均频率值 22.5 的两倍),以提供代码频率的代表性视觉比较。

Our study has several limitations. One is that the free-text method of gathering these data prevents engagement with the participant and clarification of intent. With this format, respondents have the ability to address a broad array of topics which promotes variety in their responses but limits our control over what the subjects choose to discuss. Focus groups with postdoctoral participants can explore in more depth the benefits and challenges perceived by postdocs. Due to the subjective nature of the survey respondents’ experiences, much of this work also reveals the postdoctoral trainees’ perceptions rather than absolute truths or facts about the scientific and career development process. Another limitation is that this sample is not random, and therefore frequency counts should be considered in this context. Given the large number of responses, the frequency by which codes appear can be helpful in understanding trends and emphasis in the sample, but not for comparing significance across codes. In addition, the sample population consists of postdoctoral scholars from top-ranked US universities and institutions, so their perspectives reflect the experience of those who train in similar environments. However, it is important to note that postdoctoral appointees at the top 100 institutions in the country (n = 56,092) account for approximately 88% of the total number of postdocs in the United States (n = 63,861) [38]. Therefore, our sample is representative of a significant portion of the U.S. postdoc population.

我们的研究有几个局限性。一个是收集这些数据的自由文本方法阻止了与参与者的互动和意图的澄清。通过这种形式,受访者有能力解决广泛的话题,这促进了他们回答的多样性,但限制了我们对主题选择讨论内容的控制。有博士后参与者的焦点小组可以更深入地探索博士后所看到的好处和挑战。由于调查受访者经历的主观性质,这项工作的大部分还揭示了博士后实习生的看法,而不是关于科学和职业发展过程的绝对真理或事实。另一个限制是此样本不是随机的,因此在这种情况下应考虑频率计数。鉴于响应数量众多,代码出现的频率有助于理解样本中的趋势和重点,但不适用于比较代码之间的显著性。此外,样本人群由来自美国一流大学和机构的博士后学者组成,因此他们的观点反映了在类似环境中接受培训的人的经验。然而,需要注意的是,美国排名前 100 的机构(n = 56,092)的博士后任命人员约占美国博士后总数(n = 63,861)的 88% [38]。因此,我们的样本代表了美国博士后人口的很大一部分。

Overall, our study shows that most postdocs understand the travails and risks associated with pursuing a tenure-track faculty position in academia. Many perceive the challenges as surmountable and the reward of an academic research career worthwhile. As noted by one postdoc, “Being a successful academic researcher is somewhat akin to pursuing a career in music performance or professional sports. Science and research must be your real passion for which you are willing to work extremely hard and sacrifice. And even with hard work and sacrifice, and of course the requisite level of talent, you may not make it to the big leagues. Be sure you are willing to take this risk and that you can enjoy the journey no matter what happens.” These accounts should benefit students and trainees interested in pursuing a research career in academia by helping them make more informed decisions about their career path, ultimately enhancing the scientific workforce.总体而言,我们的研究表明,大多数博士后都了解在学术界追求终身教职职位所带来的痛苦和风险。许多人认为这些挑战是可以克服的,学术研究生涯的回报是值得的。正如一位博士后所指出的那样,“成为一名成功的学术研究人员有点类似于从事音乐表演或职业体育事业。科学和研究必须是你真正的激情所在,你愿意为此付出极大的努力和牺牲。即使付出努力和牺牲,当然还有必要的天赋水平,你也可能无法进入大联盟。确保你愿意冒这个风险,无论发生什么,你都可以享受这段旅程。这些账户应该使有兴趣在学术界从事研究事业的学生和受训者受益,帮助他们对自己的职业道路做出更明智的决定,最终增强科学工作者队伍。

Supporting information 支持信息

S1 File. Responses of 994 postdoctoral researchers to a single, open-ended survey question: “What advice would you give to someone thinking about an academic research career?”.

S1 文件。994 名博士后研究人员对一个开放式调查问题的回答:“您对考虑从事学术研究事业的人有什么建议?

Click here for additional data file. (132.1KB, docx)

S1 Table. Full list of codes derived from the survey responses.

S1 表。从调查响应派生的代码的完整列表。

Click here for additional data file. (23.7KB, docx)

S2 Table. Original codes divided into 6 categories under the major theme, Life in Academia.

S2 表。原始代码在主要主题 Life in Academia 下分为 6 类。

Click here for additional data file. (16.9KB, docx)

S3 Table. Original codes divided into 14 categories under the major theme, Strategies for Success.

S3 表。原始代码在主要主题 Strategies for Success 下分为 14 个类别。

Click here for additional data file. (21.3KB, docx)

Acknowledgments 确认

The authors wish to thank Dr. Mary E. Charlson, Dr. Avelino Amado and Dr. Leslie Krushel for helpful comments.作者感谢 Mary E. Charlson 博士、Avelino Amado 博士和 Leslie Krushel 博士的有益评论。

Data Availability 数据可用性

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

所有相关数据都在论文及其支持信息文件中。

Funding Statement 资助声明

WML acknowledges support by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002384. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

WML 感谢美国国立卫生研究院国家促进转化科学中心(National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health)的 UL1TR002384 号支持。内容完全由作者负责,并不一定代表美国国立卫生研究院的官方观点。资助者在研究设计、数据收集和分析、发表决定或手稿准备方面没有任何作用。

References

- 1.Many junior scientists need to take a hard look at their job prospects. Nature. 2017;550(7677):429. Epub 2017/10/27. 10.1038/550429a .

- 2.Yadav A, Seals C. Taking the next step: supporting postdocs to develop an independent path in academia. International Journal of STEM Education. 2019;6(1):15. 10.1186/s40594-019-0168-1

- 3.The plight of young scientists. Nature. 2016;538(7626):443. Epub 2016/10/28. 10.1038/538443a .

- 4.Maher B, Sureda Anfres M. Young scientists under pressure: what the data show. Nature. 2016;538(7626):444. Epub 2016/10/28. 10.1038/538444a .

- 5.Price RM, Kantrowitz-Gordon I, Gordon SE. Competing Discourses of Scientific Identity among Postdoctoral Scholars in the Biomedical Sciences. CBE life sciences education. 2018;17(2):ar29–ar. 10.1187/cbe.17-08-0177 .

- 6.Garrison HH, Stith AL, Gerbi SA. Foreign postdocs: the changing face of biomedical science in the U.S. The FASEB Journal. 2005;19(14):1938–42. 10.1096/fj.05-1203ufm .

- 7.Zimmerman AM. Navigating the path to a biomedical science career. PloS one. 2018;13(9):e0203783. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203783

- 8.Kamerlin SC. Hypercompetition in biomedical research evaluation and its impact on young scientist careers. International microbiology: the official journal of the Spanish Society for Microbiology. 2015;18(4):253–61. Epub 2016/09/10. 10.2436/20.1501.01.257 .

- 9.Blank R, Daniels RJ, Gilliland G, Gutmann A, Hawgood S, Hrabowski FA, et al. A new data effort to inform career choices in biomedicine. Science. 2017;358(6369):1388. 10.1126/science.aar4638

- 10.Fuhrmann CN, Halme DG, O’Sullivan PS, Lindstaedt B, Siegel V. Improving Graduate Education to Support a Branching Career Pipeline: Recommendations Based on a Survey of Doctoral Students in the Basic Biomedical Sciences. CBE—Life Sciences Education. 2011;10(3):239–49. 10.1187/cbe.11-02-0013

- 11.Gibbs KD Jr., Griffin KA. What do I want to be with my PhD? The roles of personal values and structural dynamics in shaping the career interests of recent biomedical science PhD graduates. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2013;12(4):711–23. 10.1187/cbe.13-02-0021

- 12.Gibbs KD Jr., McGready J, Bennett JC, Griffin K. Biomedical Science Ph.D. Career Interest Patterns by Race/Ethnicity and Gender. PloS one. 2014;9(12):e114736. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114736

- 13.Wild R. The autopilot postdoc: Naturejobs Blog. 2020.

- 14.Sauermann Roach. Why pursue the postdoc path? Science. 2016;352(6286):663. 10.1126/science.aaf2061

- 15.Schnoes AM, Caliendo A, Morand J, Dillinger T, Naffziger-Hirsch M, Moses B, et al. Internship Experiences Contribute to Confident Career Decision Making for Doctoral Students in the Life Sciences. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2018;17(1). Epub 2018/02/17. 10.1187/cbe.17-08-0164

- 16.Nowell L, Alix Hayden K, Berenson C, Kenny N, Chick N, Emery C. Professional learning and development of postdoctoral scholars: a scoping review protocol. Systematic reviews. 2018;7(1):224. Epub 2018/12/07. 10.1186/s13643-018-0892-5

- 17.Rybarczyk BJ, Lerea L, Whittington D, Dykstra L. Analysis of Postdoctoral Training Outcomes That Broaden Participation in Science Careers. CBE life sciences education. 2016;15(3):ar33. 10.1187/cbe.16-01-0032 .

- 18.Mathur A, Cano A, Kohl M, Muthunayake NS, Vaidyanathan P, Wood ME, et al. Visualization of gender, race, citizenship and academic performance in association with career outcomes of 15-year biomedical doctoral alumni at a public research university. PloS one. 2018;13(5):e0197473–e. 10.1371/journal.pone.0197473 .

- 19.Levitt DG. Careers of an elite cohort of U.S. basic life science postdoctoral fellows and the influence of their mentor’s citation record. BMC medical education. 2010;10:80-. 10.1186/1472-6920-10-80 .

- 20.Meyers FJ, Mathur A, Fuhrmann CN, O’Brien TC, Wefes I, Labosky PA, et al. The origin and implementation of the Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training programs: an NIH common fund initiative. FASEB J. 2016;30(2):507–14. Epub 2015/10/02. 10.1096/fj.15-276139 .

- 21.Ghaffarzadegan N, Hawley J, Larson R, Xue Y. A Note on PhD Population Growth in Biomedical Sciences. Systems research and behavioral science. 2015;23(3):402–5. 10.1002/sres.2324 PMC4503365.

- 22.McConnell SC, Westerman EL, Pierre JF, Heckler EJ, Schwartz NB. United States National Postdoc Survey results and the interaction of gender, career choice and mentor impact. eLife. 2018;7:e40189. 10.7554/eLife.40189

- 23.Levitt M, Levitt JM. Future of fundamental discovery in US biomedical research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2017;114(25):6498–503. 10.1073/pnas.1609996114

- 24.Woolston C. Postdoc survey reveals disenchantment with working life. Nature. 2020;587(7834):505–8. 10.1038/d41586-020-03191-7

- 25.Lambert WM, Wells MT, Cipriano MF, Sneva JN, Morris JA, Golightly LM. Career choices of underrepresented and female postdocs in the biomedical sciences. eLife. 2020;9:e48774. 10.7554/eLife.48774

- 26.Lorden JF, Kuh CV, Voytuk JA. Representation of Underrepresented Minorities. (US) NRC, editor. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. 2011. 10.17226/13213

- 27.NPA Celebrates Continued Increases to NRSA Postdoc Stipends—National Postdoctoral Association. 2020.

- 28.Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group. Biomedical Research Workforce Working Group Report (National Institutes of Health). 2012;9(19):2016.

- 29.National Academies of Sciences E, Medicine. The Next Generation of Biomedical and Behavioral Sciences Researchers: Breaking Through. Daniels R, Beninson L, editors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. 192 p. [PubMed]

- 30.Bankston A, McDowell GS. Monitoring the compliance of the academic enterprise with the Fair Labor Standards Act. F1000Res. 2016;5:2690. Epub 2017/10/19. 10.12688/f1000research.10086.2

- 31.Sauermann Roach. Science PhD career preferences: levels, changes, and advisor encouragement. PloS one. 2012;7(5):e36307. Epub 2012/05/09. 10.1371/journal.pone.0036307

- 32.Gibbs KD Jr., McGready J, Griffin K. Career Development among American Biomedical Postdocs. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14(4):ar44. 10.1187/cbe.15-03-0075

- 33.Roach M, Sauermann H. The declining interest in an academic career. PloS one. 2017;12(9):e0184130. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184130

- 34.Polka JK, Krukenberg KA, McDowell GS. A call for transparency in tracking student and postdoc career outcomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26(8):1413–5. Epub 2015/04/15. 10.1091/mbc.E14-10-1432

- 35.Lent RW, Brown SD, Hackett G. Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 1994;45(1):79–122. 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

- 36.Vroom VH. Work and Motivation. New York: Wiley; 1964.

- 37.Bieschke KJ. Factor Structure of the Research Outcome Expectations Scale. Journal of Career Assessment. 2000;8(3):303–13. 10.1177/106907270000800307

- 38.National Science Foundation NCfSaES. Survey of Graduate Students and Postdoctorates in Science and Engineering, Fall 2016 Arlington, VA 2018. Available from: https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/gradpostdoc/2016/.

- 39.Schaller MD, McDowell G, Porter A, Shippen D, Friedman KL, Gentry MS, et al. What’s in a name? eLife. 2017;6:e32437. 10.7554/eLife.32437 .

- 40.Shen H. Employee benefits: Plight of the postdoc. Nature. 2015;525(7568):279–81. Epub 2015/09/12. 10.1038/nj7568-279a .

- 41.van der Weijden I, Teelken C, de Boer M, Drost M. Career satisfaction of postdoctoral researchers in relation to their expectations for the future. Higher Education. 2016;72(1):25–40. 10.1007/s10734-015-9936-0

- 42.Grinstein A, Treister R. The unhappy postdoc: a survey based study. F1000Res. 2017;6:1642–. 10.12688/f1000research.12538.2 .

- 43.Watts SW, Chatterjee D, Rojewski JW, Shoshkes Reiss C, Baas T, Gould KL, et al. Faculty perceptions and knowledge of career development of trainees in biomedical science: What do we (think we) know? PloS one. 2019;14(1):e0210189. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210189

via: PLoS One. 2021 May 6;16(5):e0250662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250662

-

Postdocs’ advice on pursuing a research career in academia: A qualitative analysis of free-text survey responses - PMC

1056

1056

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?