最近看了一篇姚顺雨写的文章叫《The Second Half》,该文章发表于2025年4月25日。本文阐述人工智能的下半场是定义问题,找到能通过人工智能解决的实际问题是什么,以及如何衡量这个人工智能解决方案的实际价值。下半场的参与者可以通过构建有用的产品来建立价值数十亿甚至数千亿美元的公司。原文地址请点击查看原文。

以下是译文,我把关键的内容标注了加粗和下划线!这篇文章我整理了几个小时希望对大家有帮助。

1、摘要:我们正处于人工智能的中场。

数十年来,人工智能主要致力于开发新的训练方法和模型。这些努力取得了成功:从国际象棋和围棋的世界冠军,到SAT和律师资格考试的高分,再到国际数学奥林匹克竞赛(IMO)和国际信息学奥林匹克竞赛(IOI)的金牌,这些成就背后是人工智能方法的根本性创新:搜索、深度强化学习、扩展和推理。随着时间的推移,事情变得越来越好。

那么,现在有什么突然不同了吗?

用三个词简单来说:强化学习终于奏效(RL finally works)。更准确地说:强化学习终于能够泛化了。经过几次重大弯路和一系列里程碑式的成就,我们终于找到了一种能够使用语言和推理解决广泛强化学习任务的可行方法。即使在一年前,如果你告诉大多数人工智能研究人员,一个单一的方法可以应对软件工程、创意写作、IMO级别的数学、鼠标和键盘操作以及长篇问答——他们会嘲笑你的幻想。这些任务每一个都极其困难,许多研究人员花费整个博士生涯专注于其中的一个狭窄领域。

然而,这一切都发生了。

那么,接下来会发生什么?人工智能的下半场——从现在开始——将把重点从解决问题转移到定义问题。在这个新时代,评估将比训练更重要。我们不再只是问:“我们能否训练一个模型来解决X?”而是问:“我们应该训练人工智能去做什么,以及如何衡量真正的进步?”要在下半场取得成功,我们需要及时转变思维方式和技能,这些思维方式和技能可能更接近产品经理。

2、人工智能的上半场

为了理解上半场,我们来看看上半场的赢家。你认为到目前为止最有影响力的AI论文是什么?

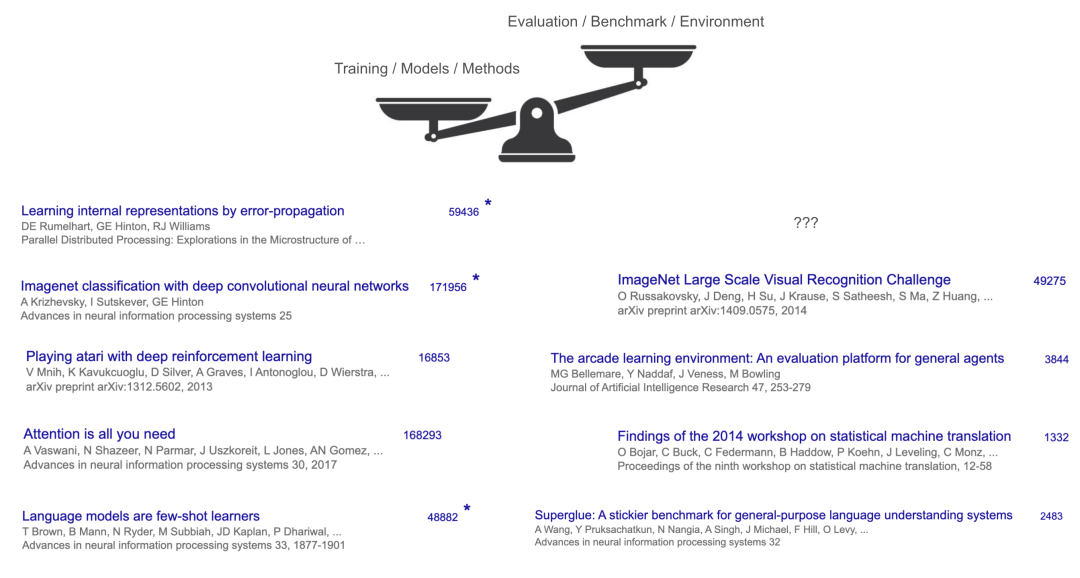

我尝试了斯坦福大学224N课程的测验,答案并不令人惊讶:Transformer、AlexNet、GPT-3等。这些论文的共同点是什么?它们提出了一些用于训练更好模型的基本突破。此外,它们还通过在某些基准测试上展示一些(显著的)改进来发表论文。

然而,还有一个潜在的共同点:这些“赢家”都是训练方法或模型,而不是基准测试或任务。即使是被认为最具影响力的基准测试之一的ImageNet,其引用次数也不及AlexNet的三分之一。在其他地方,方法与基准测试的对比甚至更加明显——例如,Transformer的主要基准测试是WMT’14,其研讨会报告的引用次数约为1300次,而Transformer的引用次数超过16万次。

这说明了上半场的规则:专注于构建新的模型和方法,而评估和基准测试是次要的(尽管为了使论文系统运作是必要的)。

为什么?一个很大的原因是,在人工智能的上半场,方法比任务更难、更令人兴奋。从头开始创建一种新的算法或模型架构——比如反向传播算法、卷积网络(AlexNet)或GPT-3中使用的Transformer——需要非凡的洞察力和工程能力。相比之下,为人工智能定义任务往往感觉更直接:我们只是将人类已经做的事情(如翻译、图像识别或棋类游戏)转化为基准测试。不需要太多洞察力甚至工程能力。

方法也往往比单个任务更具通用性和广泛适用性,这使得它们特别有价值。例如,Transformer架构最终推动了计算机视觉(CV)、自然语言处理(NLP)、强化学习(RL)等多个领域的进步——远远超出了它最初证明自己的单一数据集(WMT’14翻译)。一种伟大的新方法可以在许多不同的基准测试中取得进步,因为它简单且通用,因此其影响往往超出单个任务。

这种游戏规则已经运作了数十年,并激发了改变世界的想法和突破,这些突破通过在各个领域不断提高的基准测试性能表现出来。为什么游戏规则会改变呢?因为这些想法和突破的积累在解决任务方面创造了一个有效的“配方”。

3、AI的有效配方

配方的成分并不令人惊讶,包括大规模语言预训练、数据和计算的规模扩大以及推理和行动的概念。这些听起来可能像是你在旧金山每天都能听到的流行语,但为什么称它们为配方呢?

我们可以通过强化学习(RL)的视角来理解这一点,强化学习通常被认为是人工智能的“终局”——毕竟,从理论上讲,RL保证能够在游戏中获胜,而且实际上很难想象没有RL的超人类系统(例如AlphaGo)。

在RL中,有三个关键组成部分:算法、环境和先验知识。

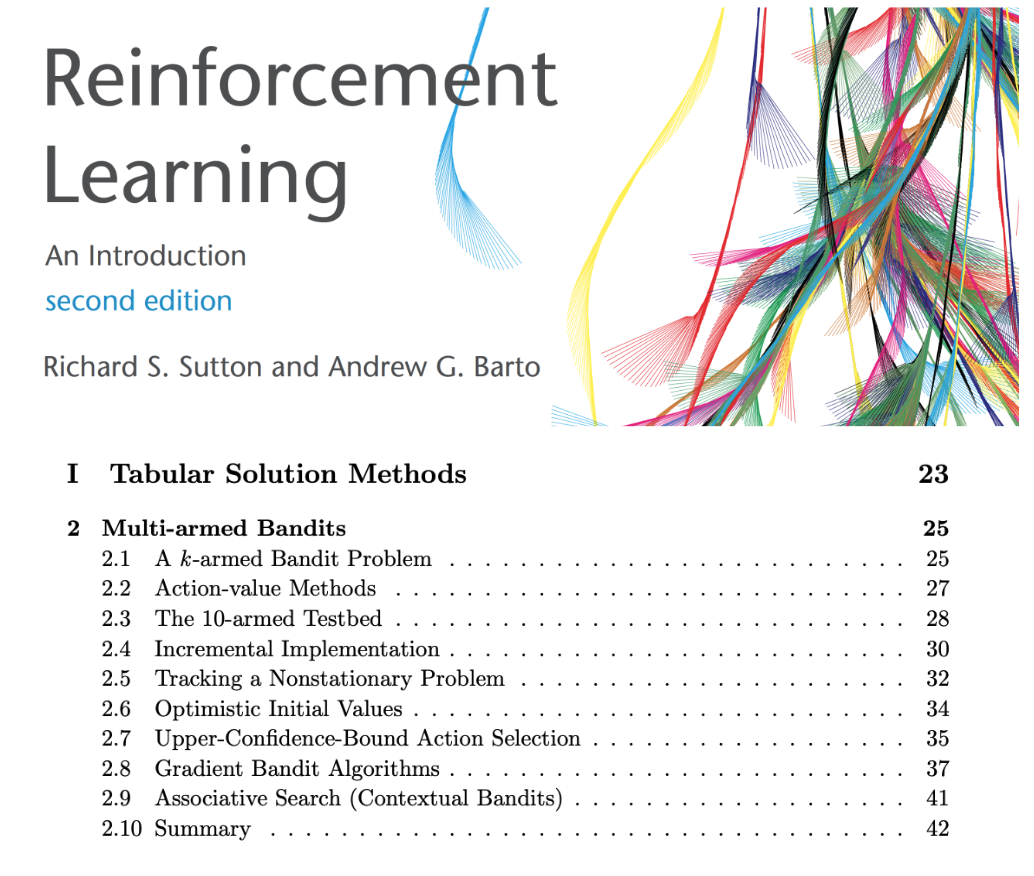

长期以来,RL研究人员主要关注算法(例如REINFORCE, DQN, TD-learning, actor-critic, PPO, TRPO……)——这是智能体学习的智力核心——而将环境和先验知识视为固定或最小化的。例如,Sutton和Barto的经典教科书几乎只关注算法,几乎没有提到环境或先验知识。

然而,在深度RL时代,实证研究表明环境确实很重要:算法的性能往往高度依赖于其开发和测试的环境。如果你忽略环境,你可能会构建一个只在玩具环境中表现出色的“最优”算法。那么,为什么我们不先确定我们真正要解决的环境,然后找到最适合它的算法呢?

这正是OpenAI最初的计划。它构建了Gym,一个用于各种游戏的标准RL环境,然后是World of Bits和Universe项目,试图将互联网或计算机变成一个游戏。这是一个好计划,不是吗?一旦我们将所有数字世界转化为环境,用智能的RL算法解决它,我们就有了数字通用人工智能(AGI)。

一个好计划,但并没有完全奏效。OpenAI在这条道路上取得了巨大进展,使用RL解决了Dota、机器人手等问题。但它从未接近解决计算机使用或网络导航的问题,而且在不同领域工作的RL智能体也无法相互迁移。缺少了什么?

直到GPT-2或GPT-3出现,才发现缺失的部分是先验知识。你需要强大的语言预训练,将一般常识和语言知识提炼到模型中,然后可以对其进行微调,使其成为网络(WebGPT)或聊天(ChatGPT)智能体(并改变世界)。事实证明,RL中最重要的部分可能甚至不是RL算法或环境,而是先验知识,而这些先验知识可以通过与RL完全无关的方式获得。

语言预训练为聊天创造了良好的先验知识,但并不同样适用于控制计算机或玩电子游戏。为什么?这些领域与互联网文本的分布相距较远,而简单地在这些领域进行SFT/RL泛化效果很差。我在2019年注意到这个问题,当时GPT-2刚刚问世,我在其基础上进行了SFT/RL,以解决基于文本的游戏——CALM是世界上第一个通过预训练语言模型构建的智能体。但该智能体需要数百万RL步骤才能在一个游戏中取得进步,而且无法迁移到新游戏。

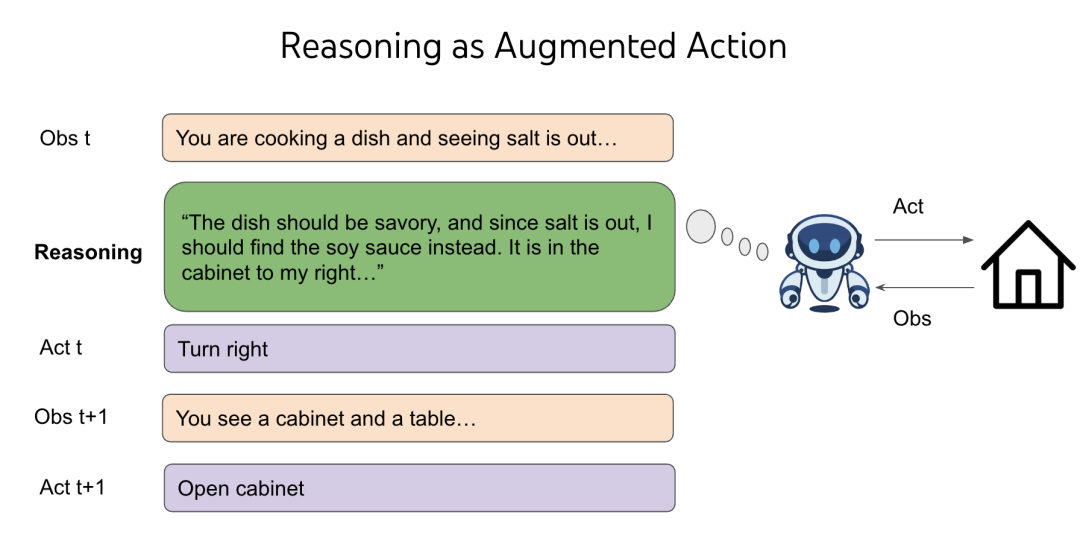

尽管这正是RL的特性,RL研究人员对此并不感到奇怪,但我发现这很奇怪,因为我们人类可以轻松地玩一个新游戏,并且在零样本的情况下表现得更好。然后我迎来了人生中的第一个“顿悟”时刻——我们之所以能够泛化,是因为我们可以选择做不仅仅是“走到柜子2”、“用钥匙1打开箱子3”或“用剑杀掉地牢”之类的事情,我们还可以选择思考类似“地牢很危险,我需要武器来战斗。没有可见的武器,也许我需要在锁着的箱子或柜子里找到一个。箱子3在柜子2里,我先去那里把它打开”之类的事情。

思考或推理是一种奇特的行动——它不会直接影响世界,但却拥有一个开放的、无限组合的空间——你可以思考一个词、一句话、整篇文章,甚至是10000个随机的英文单词,但你周围的世界不会立即改变。在经典RL理论中,这是一个糟糕的交易,使决策变得不可能。想象一下,你需要在两个箱子中选择一个,其中一个箱子里有100万美元,另一个是空的。你期望获得50万美元。现在想象我在其中增加了无数个空箱子。你期望获得的金额就变成了零。但通过将推理加入任何RL环境的行动空间,我们可以利用语言预训练的先验知识来泛化,并且可以为不同决策提供灵活的测试时计算。

这是一件非常神奇的事情,我在这里可能没有完全讲清楚,我可能需要再写一篇博客来专门解释它。你可以阅读ReAct了解推理对智能体的原始故事,也可以阅读我当时的想法。现在,我的直观解释是:即使你增加了无数个空箱子,你在一生中见过各种游戏中的它们,选择这些箱子可以让你更好地在任何给定游戏中选择装有钱的箱子。我的抽象解释是:

通过智能体中的推理能力实现了语言的泛化。

一旦我们有了正确的RL先验知识(语言预训练)和RL环境(将语言推理作为行动),事实证明RL算法可能就是最不重要的部分了。因此,我们有了o系列、R1、深度研究、计算机使用的智能体,还有很多更多即将出现。真是一个讽刺的转折!长期以来,RL研究人员一直更关心算法,而不是环境,而且没有人关注先验知识——所有RL实验本质上都是从零开始的。但我们花了数十年的弯路才意识到,也许我们的优先级应该完全颠倒过来。

正如史蒂夫·乔布斯所说:你不能向前连接这些点;你只能向后连接它们。

4、人工智能的下半场

这个配方正在彻底改变游戏规则。回顾上半场的游戏规则:

我们开发新的训练方法或模型,以提高基准测试的性能。

我们创建更难的基准测试,并继续这个循环。

这个游戏规则正在被破坏,因为:

这个配方本质上已经标准化和工业化了基准测试的性能提升,而不需要太多新的想法。随着配方的扩展和泛化,你针对特定任务的新方法可能只能将其性能提高5%,而下一个o系列模型可能会在没有明确针对它的情况下将其性能提高30%。

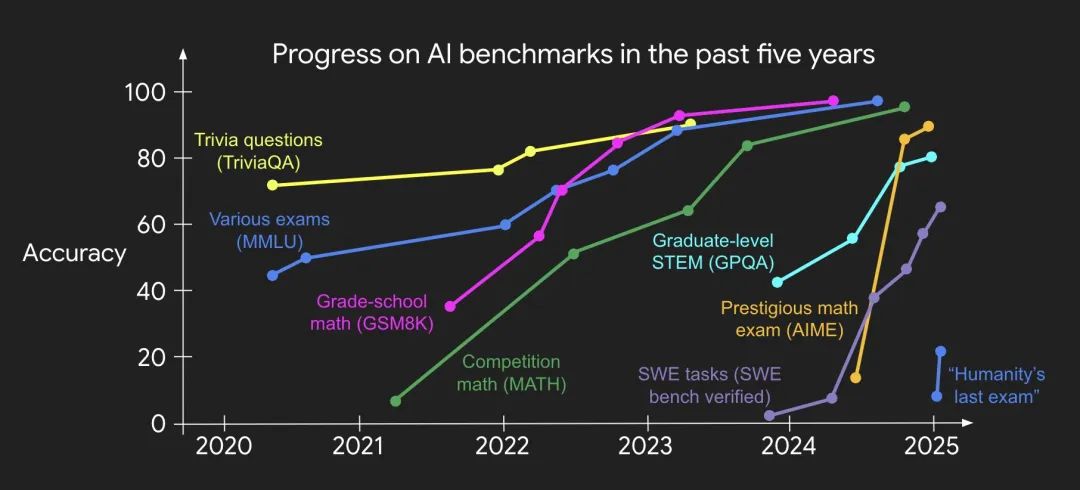

即使我们创建了更难的基准测试,很快(而且越来越快)它们也会被配方解决。我的同事Jason Wei制作了一张精美的图表,很好地可视化了这一趋势:

那么,在下半场还有什么可以玩的呢?如果不再需要新方法,而更难的基准测试也会越来越快地被解决,我们应该做什么?

我认为我们应该从根本上重新思考评估。这意味着不仅仅是创建新的、更难的基准测试,而是从根本上质疑现有的评估方法,并创建新的评估方法,以便我们被迫发明超出现有配方的新方法。这很难,因为人类有惯性,很少质疑基本假设——你只是把它们当作理所当然,而没有意识到它们是假设,而不是定律。

为了说明惯性,假设你发明了历史上最成功的基于人类考试的评估之一。这是一个在2021年非常大胆的想法,但3年后它已经饱和了。你会怎么做?最有可能的是创建一个更难的考试。或者假设你解决了简单的编程任务。你会怎么做?最有可能的是找到更难的编程任务来解决,直到达到国际信息学奥林匹克竞赛(IOI)金牌水平。

惯性是自然的,但问题是:人工智能已经在国际象棋和围棋中击败了世界冠军,在SAT和律师资格考试中超越了大多数人,并在国际信息学奥林匹克竞赛(IOI)和国际数学奥林匹克竞赛(IMO)中达到了金牌水平。但世界并没有发生太大变化,至少从经济和国内生产总值(GDP)的角度来看。

我称这为效用问题,并认为这是人工智能最重要的问题。

也许我们会很快解决效用问题,也许不会。不管怎样,这个问题的根本原因可能出人意料地简单:我们的评估的方法在许多基本方面与现实世界的设定不同。举两个例子:

假设一 :评估“应该”自动运行

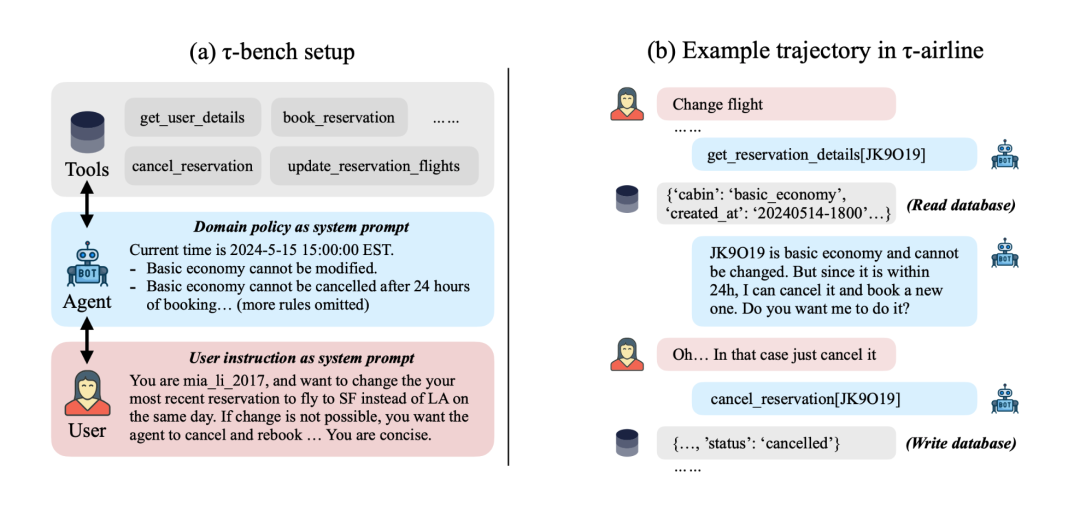

因此通常智能体接收任务输入,自主执行任务,然后接收任务奖励。但在现实中,智能体需要在整个任务过程中与人类互动——你不会给客户服务发送一条超长的信息,等待10分钟,然后期望一个详细的回复来解决一切问题。通过质疑这种设置,新的基准测试被发明出来,要么引入真实的人类(例如Chatbot Arena),要么引入用户模拟(例如tau-bench)。

假设二 :被评估的任务应该是独立同分布(IID)

如果你有一个包含500个任务的测试集,你会独立运行每个任务,平均任务指标,然后得到一个总体指标。但在现实中,你是按顺序而不是并行解决任务的。一位谷歌软件工程师(SWE)在越来越熟悉代码库的过程中,会越来越擅长解决google3问题,但一个SWE智能体在同一个代码库中解决许多问题时却无法获得这样的熟悉度。我们显然需要长期记忆方法(而且确实有),但学术界没有适当的基准测试来证明这种需求,甚至没有足够的勇气去质疑机器学习的基础假设——独立同分布(i.i.d.)。

这些假设“一直”如此,而在人工智能的上半场,在这些假设下开发基准测试是可以的,因为当智能水平较低时,提高智能水平通常会提高效用。但现在,通用配方在这些假设下保证奏效。因此,下半场的新游戏规则是:

我们开发针对现实世界效用的新型评估设置或任务。

我们用配方解决它们,或者用新组件增强配方。继续这个循环。

这个游戏很难,因为它不熟悉。但它令人兴奋。虽然上半场的参与者解决的是视频游戏和考试,但下半场的参与者可以通过构建有用的产品来建立价值数十亿甚至数千亿美元的公司。虽然上半场充满了渐进式的方法和模型,但下半场在一定程度上过滤了它们。通用配方会压倒你的渐进式方法,除非你创造新的假设来打破配方。然后你就可以进行真正改变游戏规则的研究。

欢迎来到人工智能的下半场!

致谢

这篇博客文章基于我在斯坦福大学224N课程和哥伦比亚大学的演讲。我使用OpenAI的深度研究来阅读我的幻灯片并撰写初稿。

以下是原文内容

The Second Half

tldr: We’re at AI’s halftime.

For decades, AI has largely been about developing new training methods and models. And it worked: from beating world champions at chess and Go, surpassing most humans on the SAT and bar exams, to earning IMO and IOI gold medals. Behind these milestones in the history book — DeepBlue, AlphaGo, GPT-4, and the o-series — are fundamental innovations in AI methods: search, deep RL, scaling, and reasoning. Things just get better over time.

So what’s suddenly different now?

In three words: RL finally works. More precisely: RL finally generalizes. After several major detours and a culmination of milestones, we’ve landed on a working recipe to solve a wide range of RL tasks using language and reasoning. Even a year ago, if you told most AI researchers that a single recipe could tackle software engineering, creative writing, IMO-level math, mouse-and-keyboard manipulation, and long-form question answering — they’d laugh at your hallucinations. Each of these tasks is incredibly difficult and many researchers spend their entire PhDs focused on just one narrow slice.

Yet it happened.

So what comes next? The second half of AI — starting now — will shift focus from solving problems to defining problems. In this new era, evaluation becomes more important than training. Instead of just asking, “Can we train a model to solve X?”, we’re asking, “What should we be training AI to do, and how do we measure real progress?” To thrive in this second half, we’ll need a timely shift in mindset and skill set, ones perhaps closer to a product manager.

The first half

To make sense of the first half, look at its winners. What do you consider to be the most impactful AI papers so far?

I tried the quiz in Stanford 224N, and the answers were not surprising: Transformer, AlexNet, GPT-3, etc. What’s common about these papers? They propose some fundamental breakthroughs to train better models. But also, they managed to publish their papers by showing some (significant) improvements on some benchmarks.

There is a latent commonality though: these “winners” are all training methods or models, not benchmarks or tasks. Even arguably the most impactful benchmark of all, ImageNet, has less than one third of the citation of AlexNet. The contrast of method vs benchmark is even more drastic anywhere else —- for example, the main benchmark of Transformer is WMT’14, whose workshop report has ~1,300 citations, while Transformer had >160,000.

That illustrates the game of the first half: focus on building new models and methods, and evaluation and benchmark are secondary (although necessary to make the paper system work).

Why? A big reason is that, in the first half of AI, methods were harder and more exciting than tasks. Creating a new algorithm or model architecture from scratch – think of breakthroughs like the backpropagation algorithm, convolutional networks (AlexNet), or the Transformer used in GPT-3 – required remarkable insight and engineering. In contrast, defining tasks for AI often felt more straightforward: we simply took tasks humans already do (like translation, image recognition, or chess) and turned them into benchmarks. Not much insight or even engineering.

Methods also tended to be more general and widely applicable than individual tasks, making them especially valuable. For example, the Transformer architecture ended up powering progress in CV, NLP, RL, and many other domains – far beyond the single dataset (WMT’14 translation) where it first proved itself. A great new method can hillclimb many different benchmarks because it’s simple and general, thus the impact tends to go beyond an individual task.

This game has worked for decades and sparked world-changing ideas and breakthroughs, which manifested themselves by ever-increasing benchmark performances in various domains. Why would the game change at all? Because the cumulation of these ideas and breakthroughs have made a qualitative difference in creating a working recipe in solving tasks.

The recipe

What’s the recipe? Its ingredients, not surprisingly, include massive language pre-training, scale (in data and compute), and the idea of reasoning and acting. These might sound like buzzwords that you hear daily in SF, but why call them a recipe??

We can understand this by looking through the lens of reinforcement learning (RL), which is often thought of as the “end game” of AI — after all, RL is theoretically guaranteed to win games, and empirically it’s hard to imagine any superhuman systems (e.g. AlphaGo) without RL.

In RL, there are three key components: algorithm, environment, and priors. For a long time, RL researchers focused mostly on the algorithm (e.g. REINFORCE, DQN, TD-learning, actor-critic, PPO, TRPO…) – the intellectual core of how an agent learns – while treating the environment and priors as fixed or minimal. For example, Sutton and Barto’s classical textbook is all about algorithms and almost nothing about environments or priors.

However, in the era of deep RL, it became clear that environments matter a lot empirically: an algorithm’s performance is often highly specific to the environment it was developed and tested in. If you ignore the environment, you risk building an “optimal” algorithm that only excels in toy settings. So why don’t we first figure out the environment we actually want to solve, then find the algorithm best suited for it?

That’s exactly OpenAI’s initial plan. It built gym, a standard RL environment for various games, then the World of Bits and Universe projects, trying to turn the Internet or computer into a game. A good plan, isn’t it? Once we turn all digital worlds into an environment, solve it with smart RL algorithms, we have digital AGI.

A good plan, but not entirely working. OpenAI made tremendous progress down the path, using RL to solve Dota, robotic hands, etc. But it never came close to solving computer use or web navigation, and the RL agents working in one domain do not transfer to another. Something is missing.

Only after GPT-2 or GPT-3, it turned out that the missing piece is priors. You need powerful language pre-training to distill general commonsense and language knowledge into models, which then can be fine-tuned to become web (WebGPT) or chat (ChatGPT) agents (and change the world). It turned out the most important part of RL might not even be the RL algorithm or environment, but the priors, which can be obtained in a way totally unrelated from RL.

Language pre-training created good priors for chatting, but not equally good for controlling computers or playing video games. Why? These domains are further from the distribution of Internet text, and naively doing SFT / RL on these domains generalizes poorly. I noticed the problem in 2019, when GPT-2 just came out and I did SFT / RL on top of it to solve text-based games - CALM was the first agent in the world built via pre-trained language models. But it took millions of RL steps for the agent to hillclimb a single game, and it doesn’t transfer to new games. Though that’s exactly the characteristic of RL and nothing strange to RL researchers, I found it weird because we humans can easily play a new game and be significantly better zero-shot. Then I hit one of the first eureka moment in my life - we generalize because we can choose to do more than “go to cabinet 2” or “open chest 3 with key 1” or “kill dungeon with sword”, we can also choose to think about things like “The dungeon is dangerous and I need a weapon to fight with it. There is no visible weapon so maybe I need to find one in locked boxes or chests. Chest 3 is in Cabinet 2, let me first go there and unlock it”.

Thinking, or reasoning, is a strangekind of action - it does not directly affect the external world, yet the space of reasoning is open-ended and combintocially infinite — you can think about a word, a sentence, a whole passage, or 10000 random English words, but the world around you doesn’t immediate change. In the classical RL theory, it is a terrible deal and makes decision-making impossible. Imagine you need to choose one out of two boxes, and there’s only one box with $1M and the other one empty. You’re expected to earn $500k. Now imagine I add infinite empty boxes. You’re expected to earn nothing. But by adding reasoning into the action space of any RL environment, we make use of the language pre-training priors to generalize, and we afford to have flexible test-time compute for different decisions. It is a really magicalthing and I apologize for not fully making sense of it here, I might need to write another blog post just for it. You’re welcome to read ReAct for the original story of reasoning for agents and read my vibes at the time. For now, my intuitive explanation is: even though you add infinite empty boxes, you have seen them throughout your life in all kinds of games, and choosing these boxes prepare you to better choose the box with money for any given game. My abstract explanation would be: language generalizes through reasoning in agents.

Once we have the right RL priors (language pre-training) and RL environment (adding language reasoning as actions), it turns out RL algorithm might be the most trivial part. Thus we have o-series, R1, deep research, computer-using agent, and so much more to come. What a sarcastic turn of events! For so long RL researchers cared about algorithms way more than environments, and no one paid any attention to priors — all RL experiments essentially start from scratch. But it took us decades of detours to realize maybe our prioritization should have be completely reversed.

But just like Steve Jobs said: You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.

The second half

This recipe is completely changing the game. To recap the game of the first half:

We develop novel training methods or models that hillclimb benchmarks.

We create harder benchmarks and continue the loop.

This game is being ruined because:

The recipe has essentially standardized and industried benchmark hillclimbing without requiring much more new ideas. As the recipe scales and generalizes well, your novel method for a particular task might improve it by 5%, while the next o-series model improve it by 30% without explicitly targeting it.

Even if we create harder benchmarks, pretty soon (and increasingly soon) they get solved by the recipe. My colleague Jason Wei made a beautiful figure to visualize the trend well:

Then what’s left to play in the second half? If novel methods are no longer needed and harder benchmarks will just get solved increasingly soon, what should we do?

I think we should fundamentally re-think evaluation. It means not just to create new and harder benchmarks, but to fundamentally question existing evaluation setupsand create new ones, so that we are forced to invent new methods beyond the working recipe. It is hard because humans have inertia and seldom question basic assumptions - you just take them for granted without realizing they are assumptions, not laws.

To explain inertia, suppose you invented one of the most successful evals in history based on human exams. It was an extremely bold idea in 2021, but 3 years later it’s saturated. What would you do? Most likely create a much harder exam. Or suppose you solved simply coding tasks. What would you do? Most likely find harder coding tasks to solve until you have reached IOI gold level.

Inertia is natural, but here is the problem. AI has beat world champions at chess and Go, surpassed most humans on SAT and bar exams, and reached gold medal level on IOI and IMO. But the world hasn’t changed much, at least judged by economics and GDP.

I call this the utility problem, and deem it the most important problem for AI.

Perhaps we will solve the utility problem pretty soon, perhaps not. Either way, the root cause of this problem might be deceptively simple: our evaluation setups are different from real-world setups in many basic ways. To name two examples:

- Evaluation “should” run automatically

, so typically an agent receives a task input, do things autonomously, then receive a task reward. But in reality, an agent has to engage with a human throughout the task — you don’t just text customer service a super long message, wait for 10 minutes, then expect a detailed response to settle everything. By questioning this setup, new benchmarks are invented to either engage real humans (e.g. Chatbot Arena) or user simulation (e.g. tau-bench) in the loop.

- Evaluation “should” run i.i.d.

If you have a test set with 500 tasks, you run each task independently, average the task metrics, and get an overall metric. But in reality, you solve tasks sequentially rather than in parallel. A Google SWE solves google3 issues increasingly better as she gets more familiar with the repo, but a SWE agent solves many issues in the same repo without gaining such familiarity. We obviously need long-term memory methods (and there are), but academia does not have the proper benchmarks to justify the need, or even the proper courage to question i.i.d. assumption that has been the foundation of machine learning.

These assumptions have “always” been like this, and developing benchmarks in these assumptions were fine in the first half of AI, because when the intelligence is low, improving intelligence generally improves utility. But now, the general recipe is guaranteed to work under these assumptions. So the way to play the new game of the second half is

We develop novel evaluation setups or tasks for real-world utility.

We solve them with the recipe or augment the recipe with novel components. Continue the loop.

This game is hard because it is unfamiliar. But it is exciting. While players in the first half solve video games and exams, players in the second half get to build billion or trillion dollar companies by building useful products out of intelligence. While the first half is filled with incremental methods and models, the second half filters them to some degree. The general recipe would just crush your incremental methods, unless you create new assumptions that break the recipe. Then you get to do truly game-changing research.

Welcome to the second half!

Acknowledgements

This blog post is based on my talk given at Stanford 224N and Columbia. I used OpenAI deep research to read my slides and write a draft.

1098

1098

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?