原文连接:《Analyzing and Comparing Lakehouse Storage Systems》

作者:Paras Jain, Peter Kraft, Conor Power, Tathagata Das, Ion Stoica, Matei Zaharia, UC Berkeley, Stanford University, Databricks(排名不分先后,共享式相等的)

目录

摘要

Lakehouse storage systems that implement ACID transactions and other management features over data lake storage, such as Delta Lake, Apache Hudi and Apache Iceberg, have rapidly grown in popularity, replacing traditional data lakes at many organizations. These open storage systems with rich management features promise to simplify management of large datasets, accelerate SQL workloads, and offer fast, direct file access for other workloads, such as machine learning. However, the research community has not explored the tradeoffs in designing lakehouse systems in detail. In this paper, we analyze the designs of the three most popular lakehouse storage systems—Delta Lake, Hudi and Iceberg—and compare their performance and features among varying axes based on these designs. We also release a simple benchmark, LHBench, that researchers can use to compare other designs. LHBench is available at https://github.com/lhbench/lhbench.

在数据湖存储上来实现ACID事务和其他管理功能的湖仓存储系统(Lakehouse Storage System),例如Delta lake、Apache Hudi和Apache Iceberg,已经迅速流行起来,在许多组织中取代了传统的数据湖。这些具有丰富管理功能的开放存储系统有望简化大型数据集的管理,加速SQL工作负载,并为其他工作负载(如机器学习)提供快速、直接的文件访问。然而,研究界并没有详细探讨在设计湖仓系统时的权衡。在该论文中,我们分析了三种最受欢迎的湖仓存储系统的设计——Delta Lake、Hudi、Iceberg,并基于这些设计比较了它们在不同维度之间的性能和特点。我们还发布了一个简单的基准测试——LHBench,研究人员可以用来比较其他设计。LHBench可在这里看到 https://github.com/lhbench/lhbench。

1 引言

The past few years have seen the rise of a new type of analytical data management system, the lakehouse, that combines the benefits of low-cost, open-format data lakes and high-performance, transactional data warehouses [22]. These systems center around open storage formats such as Delta Lake [21], Apache Hudi [4] and Apache Iceberg [6] that implement transactions, indexing and other DBMS functionality on top of low-cost data lake storage (e.g., Amazon S3) and are directly readable from any processing engine. Lakehouse systems are quickly replacing traditional data lakes: for example, over 70% of bytes written by Databricks customers go to Delta Lake [21], Uber and Netflix run their analytics stacks on on Hudi and Iceberg (respectively) [2, 27], and cloud data services such as Synapse, Redshift, EMR and Dataproc are adding support for these systems [1, 3, 8, 17]. There is also a growing amount of research on lakehouse-like systems [20, 23, 26, 30].

在过去的几年里,一种新型的分析数据管理系统湖仓兴起,它结合了低成本、开放格式的数据湖和高性能、事务性的数仓的优势[22]。这些系统以开放存储格式为中心,如Delta Lake[21]、Apache Hudi[4]和Apache Iceberg[6],它们在低成本的数据湖存储(如Amazon S3)之上实现事务、索引和其他DBMS的功能,并且可以从任何的处理引擎直接读取。湖仓系统正在迅速取代传统的数据湖:例如,Databricks客户写入的70%以上的字节都流向了Delta Lake[21],Uber和Netflix分别在Hudi和Iceberg上运行分析堆栈[2,27],云数据服务例如Synapse、Redshift、EMR和Dataproc等正在增加对这些系统的支持[1,3,8,17]。关于类似湖仓的系统也有越来越多的研究[20,23,26,30]。

Nonetheless, the tradeoffs in designing a lakehouse storage system are not well-studied. In this paper, we analyze and compare the three most popular open source lakehouse systems—Delta Lake, Hudi and Iceberg—to highlight some of these tradeoffs and identify areas for future work. We compare the systems qualitatively based on features such as transaction semantics, and quantitatively using a simple benchmark based on TPC-DS that exercises the areas where they make different design choices (LHBench). We have open sourced LHBench at https://github.com/lhbench/lhbench.

尽管如此,在设计湖仓存储系统时的权衡并没有得到很好的研究。在本文中,我们分析和比较了三种最流行的开源湖仓系统——Delta Lake、Hudi 和Iceberg,以强调其中的一些权衡,并确定未来的工作领域。我们根据事务语义等特征,并使用基于TPC-DS的简单基准测试,对系统进行了定量比较,该基准运用他们做出不同设计选择的领域(LHBench)。我们在https://github.com/lhbench/lhbench上开源了它。

Lakehouse systems are challenging to design for several reasons. First, they need to run over low-cost data lake storage systems, such as Amazon S3 or Azure Data Lake Storage (ADLS), that have relatively high latency compared to a traditional custom-built data warehousing cluster and offer weak transactional guarantees. Second, they aim to support a wide range of workload scales and objectives—from very large-scale data lake workloads that involve loading and transforming hundreds of petabytes of data, to interactive data warehouse workloads on smaller tables, where users expect sub-second latency. Third, lakehouse systems aim to be accessible from multiple compute engines through open interfaces, unlike a traditional data warehouse storage system that is co-designed with one compute engine. The protocols that these client engines use to access data need to be designed carefully to support ACID transactions, scale, and high performance, which is especially challenging when the lakehouse system runs over a high-latency object store with few built-in transactional features.

由于几个原因,湖仓系统的设计具有挑战性。首先,它们需要在低成本的数据湖存储系统上运行,例如Amazon S3或Azure数据湖存储(ADLS),与传统的定制数仓集群相比,这些系统具有相对较高的延迟,并且提供较弱的事务保证。其次,它们旨在支持广泛的工作负载规模和目标——从涉及加载和转换数百PB数据的非常大规模的数据湖工作负载,到较小表上的交互式数仓工作负载,其中用户期望亚秒级延迟。第三,湖仓系统旨在通过开放接口从多个计算引擎访问,而不像传统的数据仓库存储系统是与一个计算引擎共同设计的。需要仔细设计这些客户端引擎用于访问数据的协议,以支持ACID事务、可伸缩性和高性能,当湖仓系统运行在一个高延迟对象存储上,并且内置事务特性很少时,这尤其具有挑战性。

These challenges lead to several design tradeoffs that we see in three popular lakehouse systems used today. Some of the key design questions include:

这些挑战导致了我们在今天使用的三种流行的湖仓系统中看到的几个设计权衡。一些关键的设计问题包括:

How to coordinate transactions? Some systems do all their coordination through the object store when possible (for example, using atomic put-if-absent operations), in order to minimize the number of dependent services required to use the lakehouse. For example, with Delta Lake on ADLS, a table remains accessible as long as ADLS is available. In contrast, other systems coordinate through an external service such as the Apache Hive MetaStore, which can offer lower latency than an object store, but adds more operational dependencies and risks limiting scalability. The three systems also offered different transaction isolation levels.

如何协调事务?一些系统在可能的情况下通过对象存储完成所有的协调(例如,使用原子性的put-if-absent操作),以最大限度地减少使用湖仓所需的依赖服务的数量。例如,对于ADLS上的Delta Lake,只要ADLS可用,表就保持可访问性。相比之下,其他系统通过外部服务(如Apache Hive MetaStore)进行协调,这可以提供比对象存储更低的延迟,但增加了更多的操作依赖性和限制可伸缩性的风险。这三个系统还提供了不同的事务隔离级别。

Where to store metadata? All of the systems we analyzed aim to store table zone maps (min-max statistics per file) and other metadata in a standalone data structure for fast access during query planning, but they use different strategies, including placing the data in the object store as a separate table, placing it in the transaction log, or placing it in a separate service.

元数据存储在哪里?我们分析的所有系统都旨在将表区映射(每个文件的min-max统计信息)和其他元数据存储在一个独立的数据结构中,以便在查询计划期间快速访问,但它们使用不同的策略,包括将数据作为一个单独的表放在对象存储中,将其放在事务日志中,或将其放进一个单独服务中。

How to query metadata? Delta Lake and Hudi can query their metadata storage in a parallel job (e.g., using Spark), speeding up query planning for very large tables, but potentially adding latency for smaller tables. On the other hand, Iceberg currently does metadata processing on a single node in its client libraries.

如何查询元数据?Delta Lake和Hudi可以在并行作业中查询其元数据存储(例如,使用Spark),加快了非常大的表的查询规划,但可能会增加较小表的延迟。另一方面,Iceberg目前在其客户端库中的单个节点上进行元数据处理。

How to efficiently handle updates? Like data lakes and warehouses, lakehouse systems experience a high volume of data loading queries, including both appends and upserts (SQL MERGE). Supporting both fast random updates and fast read queries is challenging on object stores with high latency that perform best with large reads and writes. The different systems optimize for these in different ways, e.g., supporting both “copy-on-write” and “merge-on-read” strategies for when to update existing tables with new data.

如何高效地处理更新?与数据湖和数仓一样,湖仓系统也会经历大量的数据加载查询,包括append和upsert(SQL MERGE)。对于具有高延迟的对象存储来说,同时支持快速随机更新和快速读取查询是一项挑战,这些对象存储在大的读写操作中表现最好。不同的系统以不同的方式对此进行优化,例如,支持“copy-on-write”和“merge-on-read”策略,以确定何时使用新数据更新现有表。

We evaluated these tradeoffs for all three systems using Apache Spark on Amazon Elastic MapReduce—running the same engine to avoid vendor-specific engines that optimize for one format, and to instead focus on the differences that stem from the formats themselves and their client libraries. We developed a simple benchmark suite for this purpose, LHBench, that runs TPC-DS as well as microbenchmarks to test metadata management and updates on large tables. We found that there are significant differences in performance and in transactional guarantees across these systems. For read-only TPC-DS queries, performance varies by 1.7× between systems on average and ranges up to 10× for individual queries. For load and merge workloads, the differences in performance can be over 5×, based on different strategies chosen in each system, such as copy-on-write or merge-on-read. LHBench also identifies areas where we believe it is possible to improve on all three formats, including accelerating metadata operations for both small and large tables, and strategies that do better than copy-on-write and merge-on-read for frequently updated tables.

我们在Amazon Elastic MapReduce上使用Apache Spark评估了所有三个系统的这些权衡——运行相同的引擎,以避免特定于供应商的引擎针对一种格式进行的优化,而是专注于格式本身及其客户端库的差异。为此,我们开发了一个简单的基准套件LHBench,它运行TPC-DS和微基准测试大型表上的元数据管理和更新。我们发现,这些系统在性能和事务保证方面存在显著差异。对于只读TPC-DS查询,系统之间的性能平均相差1.7倍,单个查询的性能最高可达10倍。对于加载和合并工作负载,根据每个系统中选择的不同策略,如copy-on-write或merge-on-read,性能差异可能超过5倍。LHBench还确定了我们认为可以改进的所有三种格式的领域,包括加快小型和大型表的元数据操作,以及对频繁更新的表执行比copy-on-write和merge-on-read更好的策略。

2 湖仓系统

Lakehouses are data management systems based on open formats that run over low-cost storage and provide traditional analytical DBMS features such as ACID transactions, data versioning, auditing, and indexing [22]. As described in the Introduction, these systems are becoming widely used, supplanting raw data lake file formats such as Parquet and ORC at many organizations.

湖仓是基于开放格式的数据管理系统,运行在低成本存储上,并提供传统的DBMS分析功能,如ACID事务、数据版本控制、审计和索引[22]。如引言中所述,这些系统正在被广泛使用,取代了许多组织的原始数据湖文件格式,如Parquet和ORC。

Because of their ability to mix data lake and warehouse functionality, lakehouse systems are used for a wide range of workloads, often larger than those of lakes or warehouses alone. On the one hand, organizations use lakehouse systems to ingest and organize very large datasets—for example, the largest Delta Lake tables span well into the hundreds of petabytes, consist of billions of files, and are updated with hundreds of terabytes of ingested data per day [21]. On the other hand, the data warehouse capabilities of lakehouse systems are encouraging organizations to load and manage smaller datasets in them too, in order to combine these with the latest data from their ingest pipelines and build a single management system for all data. For example, most of the CPU-hours on Databricks are used to process tables smaller than 1 TB, and query durations across all tables range from sub-second to hours. New latencyoptimized SQL engines for lakehouse formats, such as Photon [24] and Presto [15], are further expanding the range of data sizes and performance regimes that users can reach.

由于湖仓系统能够结合数据湖和仓库功能,因此它们用于各种工作负载,通常比单独的湖或仓更大。一方面,组织使用湖仓系统来摄取和组织非常大的数据集——例如,最大的Delta Lake表跨度高达数百PB,由数十亿个文件组成,每天用数百TB的摄取数据进行更新[21]。另一方面,湖仓系统的数仓功能也鼓励组织在其中加载和管理较小的数据集,以便将这些数据与来自其摄入管道的最新数据相结合,并为所有数据构建一个单一的管理系统。例如,Databricks上的大部分CPU小时用于处理小于1TB的表,所有表的查询持续时间从亚秒到小时不等。SQL引擎为湖仓格式进行了新的延迟优化,如Photon[24]和Presto[15],正在进一步扩大用户可以达到的数据大小和性能范围。

The main difference between lakehouse systems and conventional analytical RDBMSs is that lakehouse systems aim to provide an open interface that allows multiple engines to directly query the same data, so that they can be used efficiently both by SQL workloads and other workloads such as machine learning and graph processing. Lakehouse systems break down the traditional monolithic system design of data warehouses: they provide a storage manager, table metadata, and transaction manager through client libraries that can be embedded in multiple engines, but allow each engine to plan and execute its own queries.

湖仓系统和传统RDBMS分析之间的主要区别在于,湖仓系统旨在提供一个开放的接口,允许多个引擎直接查询相同的数据,以便SQL工作负载和其他工作负载(如机器学习和图处理)都能有效地使用它们。湖仓系统打破了数仓的传统单片系统设计:它们通过可以嵌入多个引擎的客户端库提供存储管理器、表元数据和事务管理器,但允许每个引擎规划和执行自己的查询。

We next discuss some of the key design questions for lakehouse systems and how Delta Lake, Hudi and Iceberg implement them.

接下来,我们将讨论湖仓系统的一些关键设计问题,以及Delta Lake、Hudi和Iceberg如何实现这些问题。

2.1 事务协调

One of the most important features of lakehouse systems is transactions. Each lakehouse system we examine claims to offer ACID transaction guarantees for reads and writes. All three systems provide transactions across all records in a single table, but not across tables. However, each system implements transactions differently and provides different guarantees, as we show in Table 1.

湖仓系统最重要的特征之一是事务。我们测试的每个湖仓系统都声称为读写提供ACID事务保证。这三个系统都提供单个表中所有记录的事务,但不提供跨表的事务。然而,每个系统实现事务的方式不同,并提供不同的保证,如表1所示。

表1:湖仓系统设计特点:它们如何存储表元数据,如何为事务提供原子性,以及它们提供什么事务隔离级别。

| 表元数据 | 事务原子性 | 隔离级别 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delta Lake | 事务日志+ 元数据检查点 | Atomic Log Appends | Serializability Strict Serializability |

| Hudi | 事务日志+ 元数据表 | Table-Level Lock | Snapshot Isolation |

| Iceberg | 分层文件 | Table-Level Lock | Snapshot Isolation Serializability |

Delta Lake, Hudi, and Iceberg all implement transactions using multi-version concurrency control [5, 14, 21]. A metadata structure defines which file versions belong to the table. When a transaction begins, it reads this metadata structure to obtain a snapshot of the table, then performs all reads from this snapshot. Transactions commit by atomically updating the metadata structure. Delta Lake relies on the underlying storage service to provide atomicity through operations such as put-if-absent (coordinating through DynamoDB for storage layers that do not support suitable operations) [21], while Hudi and Iceberg use table-level locks implemented in ZooKeeper, Hive MetaStore, or DynamoDB [5]. It is worth noting that the most popular lock-based implementations, using Hive MetaStore, do not provide strong guarantees; for example, in Iceberg, it is possible for a transaction to commit a dirty write if the Hive MetaStore lock times out between a lock heartbeat and the metadata write [11].

Delta Lake、Hudi和Iceberg都使用多版本并发控制(multi-version concurrency control)来实现事务[5,14,21]。元数据结构定义了哪些文件版本属于该表。当事务开始时,它读取此元数据结构以获得表的快照,然后从该快照执行所有读取。事务通过原子性的更新元数据结构来提交。Delta Lake依靠底层存储服务通过put-if-absent(通过DynamoDB协调不支持适合操作的存储层)等操作提供原子性[21],而Hudi和Iceberg使用ZooKeeper、Hive MetaStore或DynamoDB[5]中实现的表级锁。值得注意的是,最流行的基于锁的实现,是使用Hive MetaStore,但其并没有提供强有力的保证;例如,在Iceberg中,如果Hive MetaStore锁在锁定心跳和元数据写入之间时超时,则事务可能提交脏写入[11]。

To provide isolation between transactions, Delta Lake, Hudi, and Iceberg all use optimistic concurrency control. They validate transactions before committing to check for conflicts with concurrent committed transactions. They provide different isolation levels depending on how they implement validation. By default, Hudi and Iceberg verify that a transaction does not write to any files also written to by committed transactions that were not in the transaction snapshot [5, 7]. Thus, they provide what Adya [19] terms snapshot isolation: transactions always read data from a snapshot of committed data valid as of the time they started and can only commit if, at commit time, no committed transaction has written data they intend to write. Delta by default (and Iceberg optionally) also verifies no transaction read conditions (e.g., in UPDATE/MERGE/DELETE operations) could be matched by rows in files committed by transactions not in the snapshot [7, 10]. Thus, they provide serializability: the result of a sequence of transactions is equivalent to that of some serial order of those transactions, but not necessarily the order in the transaction log. Delta can optionally perform this check for read-only operations (e.g., SELECT statements), decreasing readwrite concurrency but providing what Herlihy and Wing [28] term strict serializability: all transactions (including reads) serialize in the order they appear in the transaction log.

为了提供事务之间的隔离,Delta Lake、Hudi和Iceberg都使用了乐观并发控制(optimistic concurrency control)。它们在提交前验证事务,以检查与并发提交事务的冲突。它们根据实现验证的方式提供不同的隔离级别。默认情况下,Hudi和Iceberg验证一个事务不会写入任何文件,而提交的事务也会写入不在事务快照中的文件[5,7]。因此,它们提供了Adya[19]所说的快照隔离:事务总是从它们启动时有效的已提交数据的快照中读取数据,并且只有在提交时没有已提交的事务写入它们打算写入的数据时才能提交。默认情况下,Delta(以及Iceberg,可选的)还验证事务读取条件(例如,在UPDATE/MERGE/DELETE操作中)不能与不在快照中的事务提交的文件中的行相匹配[7,10]。因此,它们提供了serializability:事务序列的结果等同于这些事务的某个序列顺序的结果,但不一定是事务日志中的顺序。Delta可以选择性地对只读操作(例如SELECT语句)执行此检查,从而降低读写并发性,但提供了Herlihy和Wing[28]所说的严格serializability:所有事务(包括读取)都按照它们在事务日志中出现的顺序进行serialize。

2.2 元数据管理

For distributed processing engines such as Apache Spark or Presto to plan queries over a table of data stored in a lakehouse format, they need metadata such as the names and sizes of all files in the table. How fast the metadata of these objects can be retrieved puts a limit on how fast queries can complete. For example, S3’s LIST only returns 1000 keys per call and therefore can take minutes to retrieve a list of millions of files [21]. Despite their processing scalability, slow metadata processing limits data lakes from providing the same query performance as databases. Thus, efficient metadata management is a crucial aspect of the lakehouse architecture.

对于Apache Spark或Presto等分布式执行引擎来说,要对湖仓格式存储的数据表进行计划查询,它们需要元数据,例如表中所有文件的名称和大小。检索这些对象的元数据的速度限制了查询完成的速度。例如,S3的LIST每次调用只返回1000个key,因此检索数百万个文件的列表可能需要几分钟的时间[21]。尽管数据湖具有处理上的可伸缩性,但缓慢的元数据处理限制了数据湖提供能与数据库相当的查询性能。因此,有效的元数据管理是湖仓架构的一个重要方面。

To overcome the metadata API rate limits of cloud object stores, lakehouse systems leverage the stores’ higher data read rates. All three formats we examine store metadata in files kept alongside the actual data files. Listing the metadata files (much fewer in number than data files) and reading the metadata from them leads to faster query planning times than listing the data files directly from S3. Two metadata organization formats are used: tabular and hierarchical. In the tabular format, used by Delta Lake and Hudi, the metadata for a lakehouse table is stored in another, special table: a metadata table in Hudi and a transaction log checkpoint (in a combination of Parquet and JSON formats) in Delta Lake [12, 21]. Transactions do not write to this table directly, but instead write log records that are periodically compacted into the table using a merge-on-read strategy. In the hierarchical format, used by Iceberg, metadata is stored in a hierarchy of manifest files [14]. Each file in the bottom level stores metadata for a set of data files, which each file in the upper level contains aggregate metadata for a set of manifest files in the layer below. This is analogous to the tabular format, but with the upper level acting as a table index.

为了克服云对象存储的元数据API速率限制,湖仓系统利用存储更高的数据读取速率。我们的测验所有三种格式都将元数据存储在和实际数据文件一起保存的文件中。列出元数据文件(数量比数据文件少得多)并从中读取元数据比直接从S3列出数据文件能更快地进行查询计划。使用了两种元数据组织格式:表格(tabular)和层次结构。在Delta Lake和Hudi使用的表格式中,湖仓表的元数据存储在另一个特殊的表中:Hudi中的元数据表和Delta Lake中的事务日志检查点(Parquet和JSON格式的组合)[12,21]。事务不直接写入此表,而是写入日志记录,这些日志记录使用merge-on-read策略定期压缩到表中。在Iceberg使用的分层格式中,元数据存储在清单文件(manifest)的分层结构中[14]。底层的每个文件存储一组数据文件的元数据,上层的每个文件包含下层的一组清单文件的聚合元数据。这类似于表格式,但上层充当表索引。

In order to gather the data needed to plan queries, lakehouse systems adopt two different metadata access schemes with different scalability tradeoffs. Queries over Delta Lake and Hudi are typically planned in a distributed fashion, as a batch job must scan the metadata table to find all files involved in a query so they can be used in query planning. By contrast, queries over Iceberg are planned by a single node that uses the upper level of the manifest hierarchy as an index to minimize the number of reads it must make to the lower level [13]. As we show in Section 3.4, single-node planning improves performance for small queries where the overhead of distributed query planning is high, but may not scale as well as distributed query planning to full scans on large tables with many files. It is an interesting research question whether query planners can be improved to use a cost model to intelligently choose between these planning strategies.

为了收集计划查询所需的数据,湖仓系统采用了两种不同的元数据访问方案,具有不同的可扩展性权衡。对Delta Lake和Hudi的查询通常以分布式方式进行计划,因为批处理作业必须扫描元数据表以查找查询中涉及的所有文件,以便在查询计划中使用这些文件。相比之下,Iceberg的查询是由单个节点计划的,该节点使用清单层次结构的上层作为索引,以最大限度地减少对下层的读取次数[13]。正如我们在第3.4节中所展示的,单节点计划提高了分布式查询规划开销很高的小型查询的性能,但可能无法像分布式查询规划那样扩展到对包含许多文件的大型表的全扫描。查询计划器是否可以改进为使用成本模型来智能地选择这些计划策略是一个有趣的研究问题。

2.3 数据更新策略

Lakehouse storage systems adopt two strategies for updating data, with differing tradeoffs between read and write performance:

The Copy-On-Write (CoW) strategy identifies the files containing records that need to be updated and eagerly rewrites them to new files with the updated data, thus incurring a high write amplification but no read amplification.

The Merge-On-Read (MoR) strategy does not rewrite files. It instead writes out information about record-level changes in additional files and defers the reconciliation until query time, thus producing lower write amplification (i.e., faster writes than CoW) but higher read amplification (i.e., slower reads than CoW). Lower write latency at the cost of read latency is sometime desired in workloads that frequently apply record-level changes (for example, continuously replicating changes from a one database to another).

湖仓存储系统采用两种更新数据的策略,在读取和写入性能之间进行不同的权衡:

写时复制(CoW)策略识别包含需要更新记录的文件,并急切地用更新的数据将其重写为新文件,从而导致高的写放大,但没有读放大。

读时合并(MoR)策略不会重写文件。相反,它在追加文件中写入有关记录级别更改的信息,并将协调推迟到查询时间,从而产生较低的放大(即,比CoW更快的写入)但较高的读放大(例如,比CoW慢的读取)。在应用记录级别频繁更改(例如,将更改从一个数据库连续复制到另一个数据库)的工作负载中,有时需要以读取延迟为代价降低写入延迟。

All three systems support the CoW strategy, as most lakehouse workloads favor high read performance. Iceberg and Hudi currently support the MoR strategy, and Delta is planning to support it as well [9]. Iceberg (and in the future, Delta) MoR implementations use auxiliary “tombstone” files that mark records in Parquet/ORC data files. At query time, these tombstoned records are filtered out. Record updates are implemented by tombstoning the existing record and writing the updated record into Parquet/ORC files. By contrast, the Hudi implementation of MoR stores all the recordlevel inserts, deletes and updates in row-based Avro files. On query, Hudi reconciles these changes while reading data from the Parquet files. It is worth nothing that Hudi by default deduplicates and sorts the ingested data by keys, thus incurring additional write latency even when using MoR. We examine the performance of the CoW and MoR update strategies in detail in Section 3.3.

这三个系统都支持CoW策略,因为大多数湖仓工作负载都支持高读取性能。Iceberg和Hudi目前都支持MoR策略,Delta也计划支持它[9]。Iceberg(以及未来的Delta)MoR实现使用辅助的“tombstone”文件来标记Parquet/ORC数据文件中的记录。在查询时,这些逻辑删除的记录会被过滤掉。记录更新是通过删除现有记录并将更新后的记录写入Parquet/ORC文件来实现的。相比之下,Hudi的MoR实现是将所有记录级插入、删除和更新存储在基于行的Avro文件中。在查询时,Hudi在读取Parquet文件中的数据时协调这些更改。Hudi默认情况下会按key对摄入的数据进行重复数据去除和排序,因此即使在使用MoR时也会产生额外的写入延迟,这一点毫无价值。我们在第3.3节中详细研究了CoW和MoR更新策略的性能。

3 湖仓系统基准测试

In this section, we compare the three lakehouse storage systems, focusing on three main areas: end-to-end performance, performance of different data ingestion strategies, and performance of different metadata access strategies during query planning. We have open sourced our benchmark suite, LHBench, and implementations for all three formats at https://github.com/lhbench/lhbench.

在本节中,我们比较了三个湖仓存储系统,重点关注三个主要领域:端到端性能、不同数据摄取策略的性能以及查询计划期间不同元数据访问策略的性能。我们已经在 https://github.com/lhbench/lhbench 开源了测试套件LHBench。

3.1 实验设置

We run all experiments using Apache Spark on AWS EMR 6.9.0 storing data in AWS S3 using Delta Lake 2.2.0, Apache Hudi 0.12.0, and Apache Iceberg 1.1.0. This version of EMR is based on Apache Spark 3.3.0. We choose EMR because it lets us compare the three lakehouse formats fairly, as it supports all of them but is not specially optimized for any of them. We use the default out-of-the-box configuration for all three lakehouse systems and for EMR, without any manual tuning except increasing the Spark driver JVM memory size to 4 GB to eliminate out-of-memory errors. We choose to use the default configurations because lakehouse systems are, by their nature, intended to support a diverse range of workloads (from large-scale batch processing to low-latency BI), and systems that work out-of-the-box without per-workload tuning are easier for users. We perform all experiments with 16 workers on AWS i3.2xlarge instances with 8 vCPUs and 61 GiB of RAM each.

我们在AWS EMR 6.9.0上使用Apache Spark运行所有实验,使用Delta Lake 2.2.0、Apache Hudi 0.12.0和Apache Iceberg 1.1.0将数据存储在AWS S3中。此版本的EMR基于Apache Spark 3.3.0。我们选择EMR是因为它可以让我们公平地比较三种湖仓格式,因为它支持所有这些格式,但没有针对其中任何一种进行专门优化。我们对所有三个湖仓系统和EMR都使用默认的开箱即用配置,除了将Spark driver程序JVM内存大小增加到4GB以消除内存不足的错误外,没有做任何其他的手动调整。我们之所以选择使用默认配置,是因为湖仓系统本质上旨在支持各种工作负载(从大规模批处理到低延迟BI),而无需按工作负载调整,即可开箱即用的系统对用户来说更容易。我们在AWS i3.2xlarge实例上用16个worker进行了所有实验,每个实例有8个vCPU和61 GiB的RAM。

3.2 加载和查询性能

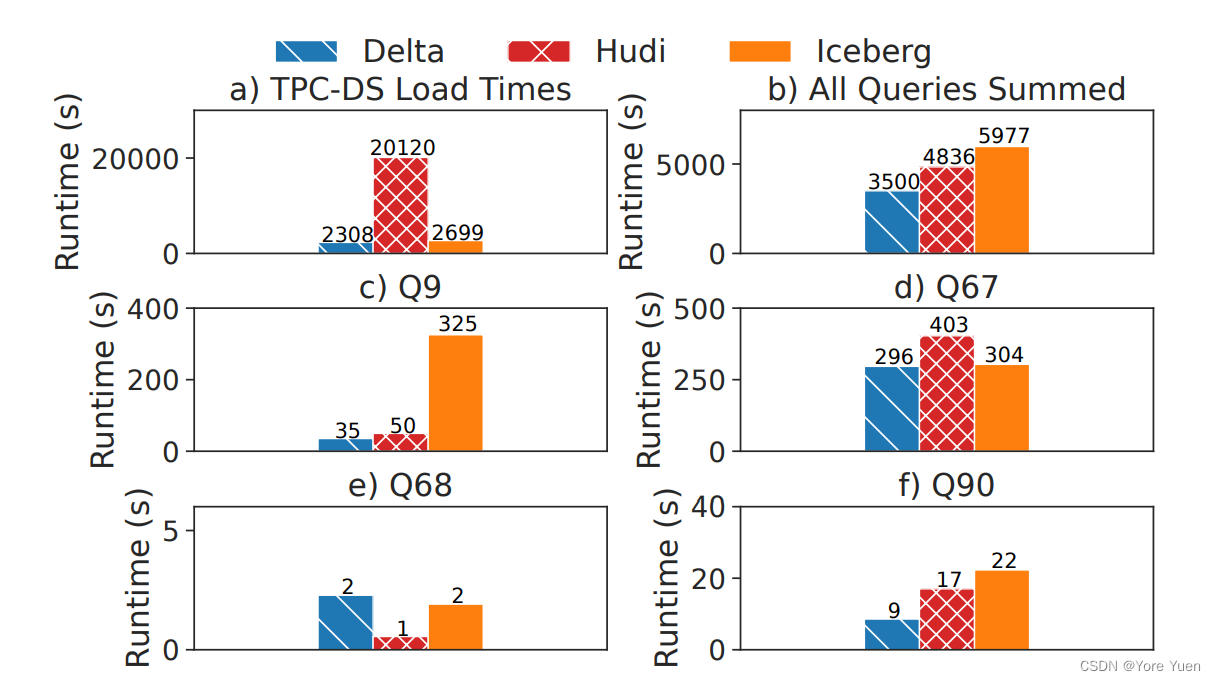

We first evaluate the effects of different data lakehouse storage formats on load times and query performance using the TPC-DS benchmark suite. We load 3 TB of TPC-DS data into Delta Lake, Hudi, and Iceberg then run all TPC-DS queries three times and report the median runtime, showing results in Figure 1.

我们首先使用TPC-DS基准测试套件评估了不同数据湖仓储格式对加载时间和查询性能的影响。我们将3 TB的TPC-DS数据加载到Delta Lake、Hudi和Iceberg中,然后运行所有TPC-DS查询三次,并报告运行时间的中位数,结果如图1所示。

图1:Delta Lake、Hudi 、Iceberg在3TB的TPC-DS加载和查询时间,包括四个差异较大的查询。

Looking at loading times, we find that Delta and Iceberg load in approximately the same time, but Hudi is almost ten times slower than either of them. This is because Hudi is optimized for keyed upserts, not bulk data ingestion, and does expensive pre-processing during data loading including key uniqueness checks and key redistribution.

从加载时间来看,我们发现Delta和Iceberg的加载时间大致相同,但Hudi几乎比它们中的任何一个要慢十倍。这是因为Hudi针对key upsert进行了优化,而不是批量数据写入,并且在数据加载期间进行了昂贵的预处理,包括key唯一性检查和key redistribution。

Looking at query times, we find that, overall, TPC-DS runs 1.4× faster on Delta Lake than on Hudi and 1.7× faster on Delta Lake than on Iceberg. To investigate the reasons for this performance difference, we examine individual queries. We look specifically at Q90, a query where Delta Lake outperforms Hudi by an especially large margin, and Q67, the most expensive query overall (accounting for 8% of total runtime). We find that Spark generates the same query plan for these two queries for all the lakehouse formats.

查询时间上看,我们发现,总体而言,TPC-DS在Delta Lake的运行速度是在Hudi的1.4倍,Delta Lake的运行速度是Iceberg的1.7倍。为了调查这种性能差异的原因,我们检查了个别的查询。我们特别关注Q90,一个Delta Lake以特别大的优势优于Hudi的查询,以及Q67,一个最昂贵的查询(占总运行时间的8%)。我们发现Spark为所有湖仓格式的这两个查询生成了相同的查询计划。

The performance difference between the three lakehouse storage systems is explained almost entirely by data reading time; this is unsurprising as the engine and query plans are the same. For example, in Q90, reading the TPC-DS Web Sales table (the largest of the six tables accessed) took 6.5 minutes in Delta Lake across all executor nodes, but 18.8 minutes in Hudi and 18.6 minutes in Iceberg. Delta Lake outperforms Hudi because Hudi targets a smaller file size. For example, a single partition of the Store Sales table is stored in one 128 MB file in Delta Lake but twenty-two 8.3 MB files in Hudi. This reduces the efficiency of columnar compression and increases overhead for the large table scans common in TPC-DS; for example, to read the Web Sales Table in Q90, the executor must read 2128 files (138 GB) in Delta Lake but 18443 files (186 GB) in Hudi. Comparing Delta Lake and Iceberg, we find that both read the same amount of bytes, but that Iceberg uses a custom-built Parquet reader in Spark that is significantly slower than the default Spark reader used by Delta Lake and Hudi. Iceberg’s support for column drops and renames required custom functionality not present in Apache Spark’s built-in Parquet reader.

三个湖仓存储系统之间的性能差异几乎完全可以用数据读取时间来解释;这并不奇怪,因为引擎和查询计划是相同的。例如,在Q90中,读取TPC-DS Web Sales表(访问的六个表中最大的一个)在所有executor节点的Delta Lake中需要6.5分钟,但在Hudi中需要18.8分钟,在Iceberg中需要18.6分钟。Delta Lake的性能优于Hudi,因为Hudi的目标文件大小较小。例如,Store Sales表的一个分区在Delta Lake中存储在一个128MB文件中,而Hudi中存储在22个8.3MB文件中。这降低了列式压缩的效率,并增加了TPC-DS中常见的大表扫描的开销;例如,要读取Q90中的Web Sales表,executor必须读取Delta Lake中的2128个文件(138 GB),但Hudi中需要读取18443个文件(186 GB)。比较Delta Lake和Iceberg,我们发现两者读取的字节数相同,但Iceberg在Spark中使用了定制的Parquet reader,该reader明显慢于Delta Lake和Hudi使用的默认Spark reader。Iceberg对列删除和重命名所需的自定义功能的支持在Apache Spark的内置Parquet reader中不存在。

While the performance of most queries follows the patterns just described, explaining the overall performance difference, there are some noteworthy exceptions. For very small queries such as Q68, the performance bottleneck is often metadata operations used in query planning. As our reported results are the medians of three consecutive runs, these queries are fastest in Hudi because it caches query plans. We examine metadata access strategies in more detail, including from cold starts, in Section 3.4. Additionally, because Iceberg uses the Spark Data Source v2 (DSv2) API instead of the Data Source v1 API (DSv1) used by Delta Lake and Hudi, Spark occasionally generates different query plans over data stored in Iceberg than over data stored in Delta Lake or Hudi. The DSv2 API is less mature and does not report some metrics useful in query planning, so this often results in less performant query plans over Iceberg. For example, in Q9, Spark optimizes a complex aggregation with a cross-join in Delta Lake and Hudi but not in Iceberg, leading to the largest relative performance difference in all of TPC-DS.

虽然大多数查询的性能都遵循刚才描述的模式,解释了整体性能的差异,但也有一些值得注意的例外。对于像Q68这样的非常小的查询,性能瓶颈通常是查询计划中使用的元数据操作。由于我们报告的结果是连续三次运行的中位数,这些查询在Hudi中是最快的,因为它缓存了查询计划。在第3.4节中,我们将更详细地研究元数据访问策略,包括冷启动。此外,由于Iceberg使用Spark Data Source v2(DSv2)API,而不是Delta Lake和Hudi使用的Data Source v1 API(DSv1),因此Spark偶尔会对存储在Iceberg中的数据生成不同于存储在Delta Lake或Hudi中的数据的查询计划。DSv2 API不够成熟,并且没有报告一些在查询计划中有用的指标,因此这通常会导致Iceberg上的查询计划性能较差。例如,在Q9中,Spark优化了一个复杂的聚合,在Delta Lake和Hudi中进行了 cross-join,但在Iceberg中没有,这导致了所有TPC-DS中最大的相对性能差异。

3.3 更新策略

To evaluate the performance of Merge-on-Read (MoR) and Copy-onWrite (CoW) update strategies, we run an end-to-end benchmark based on the TPC-DS data refresh maintenance benchmark, as well as a synthetic microbenchmark with varying merge source sizes.

为了评估读时合并(MoR)和写时复制(CoW)更新策略的性能,我们运行了一个基于TPC-DS数据刷新维护基准的端到端基准测试,以及一个具有不同合并源大小的合并微基准测试。

3.3.1 TPC-DS Refresh Benchmark(TPC-DS刷新基准测试)

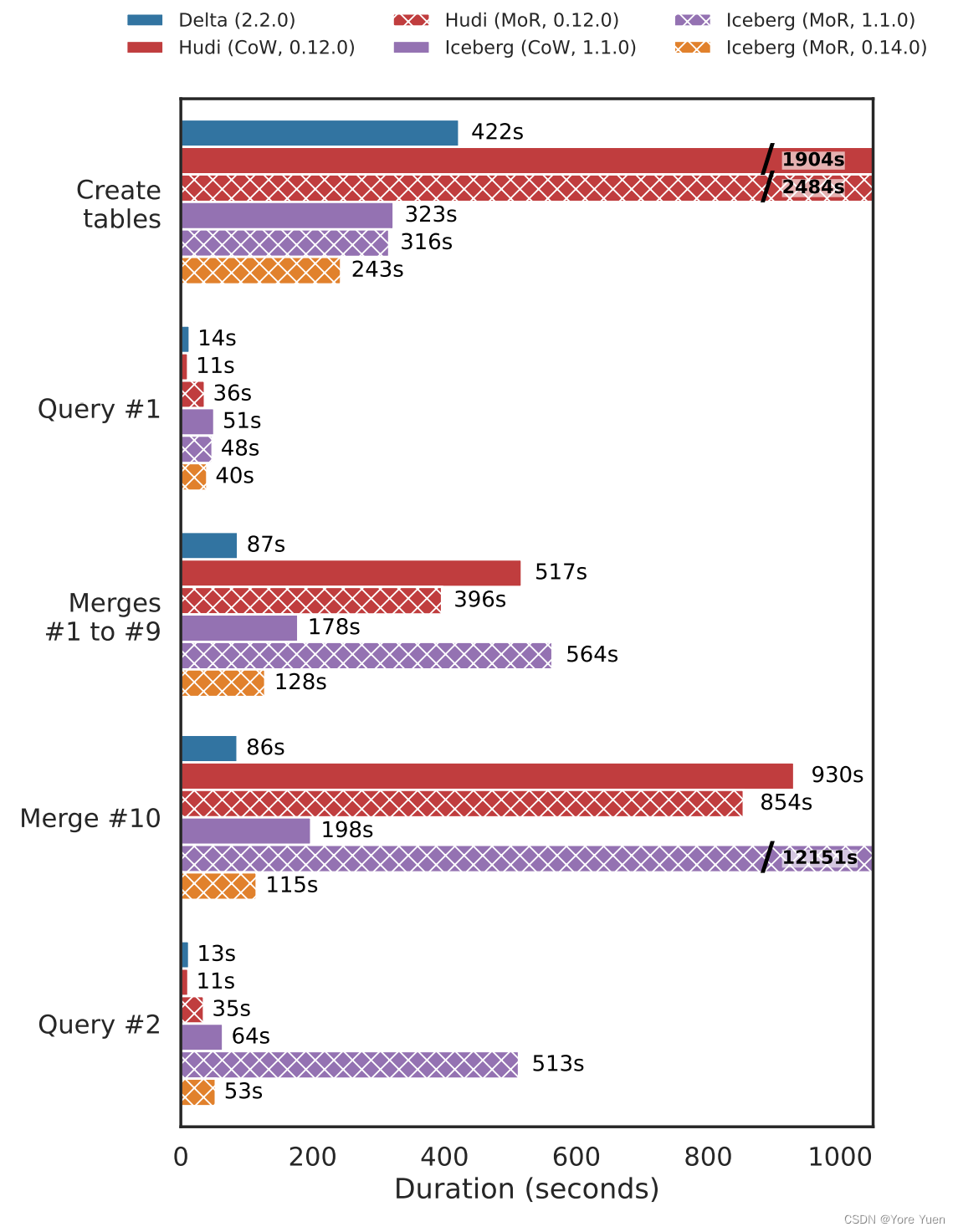

The TPC-DS benchmark specification provides a set of data refresh operations that simulate maintenance of a data warehouse [18, 31]. We evaluate Delta, Hudi, and Iceberg against a 100 GB TPC-DS dataset. We test CoW in all systems and MoR in Hudi and Iceberg only, because Delta 2.2.0 does not implement MoR. The benchmark first loads the 100 GB TPC-DS base dataset, then runs five sample queries (Q3, Q9, Q34, Q42, and Q59). It then runs a total of 10 refreshes (each for 3% of the original dataset) using the MERGE INTO operation to update rows. Finally, it reruns the five sample queries on the updated tables.

TPC-DS基准规范提供了一组模拟数仓维护的数据刷新操作[18,31]。我们根据100GB的TPC-DS数据集对Delta、Hudi和Iceberg进行了评估。我们在所有系统中测试CoW,仅在Hudi和Iceberg测试MoR,因为Delta 2.2.0没有实现MoR。基准测试首先加载100GB TPC-DS基本数据集,然后运行五个示例查询(Q3、Q9、Q34、Q42和Q59)。然后,它使用MERGE INTO操作更新行,总共运行10次刷新(每次刷新原始数据集的3%)。最后,我们对更新后的表重新运行五个示例查询。

Figure 2 shows the latency of each stage of the refresh benchmark in each system. Hudi and Delta results are run with the default EMR configuration with no change. We found that Iceberg 1.1.0 MoR consistently encountered S3 connection timeout errors in this benchmark, leading to very long running times. We tried increasing the S3 connection pool size for Iceberg runs per AWS EMR documentation [16], but it did not resolve the issue in Iceberg 1.1.0. We therefore also report results with Iceberg 0.14.0 for MoR, which performed well with the increased connection limit.

图2显示了每个系统中刷新基准测试的每个阶段的延迟。Hudi和Delta结果使用默认的EMR配置运行,没有任何更改。我们发现Iceberg 1.1.0 MOR在这个基准测试中一直遇到S3连接超时错误,导致运行时间非常长。根据AWS EMR文档[16],我们尝试增加Iceberg运行的S3连接池大小,但它没有解决Iceberg 1.1.0 中的问题。因此,我们还报告了Iceberg 0.14.0的MoR结果,该结果在连接限制增加的情况下表现良好。

图2:100GB的TPC-DS增量刷新基准测试的性能。基准测试加载数据,运行五个查询(Q3、Q9、Q34、Q42和Q59),然后将更改合并到表中十次,然后再次运行这些查询。Hudi在合并迭代10中运行了压缩,所以我们将其与1-9分开报告。由于超时错误[16],Iceberg结果在更高的S3连接池大小下运行。Delta和Hudi结果使用默认的EMR配置运行。

Merges in Hudi MoR are 1.3× faster than in Hudi CoW at the cost of 3.2× slower queries post-merge. Both Hudi CoW and MoR have poor write performance during the initial load due to additional pre-processing to distribute the data by key and rebalance write file sizes. Delta’s performance on both merges and reads is competitive, despite using only CoW, due to a combination of generating fewer files, faster scans (as discussed in Section 3.2), and a more optimized MERGE command. Merges in Iceberg version 0.14.0 with MoR are 1.4× faster than CoW. Post-merge query performance remains similar between table modes.

Hudi MoR中的合并速度比Hudi CoW快1.3倍,合并后的查询速度慢3.2倍。在初始加载期间,Hudi CoW和MoR的写性能都很差,因为需要进行额外的预处理,按key分发数据并重新平衡写文件大小。尽管只使用CoW,但由于生成更少的文件、更快的扫描(如第3.2节所述)和更优化的MERGE命令,Delta在合并和读取方面的性能都具有竞争力。在Iceberg 0.14.0版本中MoR合并比CoW快1.4倍。合并后查询的性能在表模式之间保持相似。

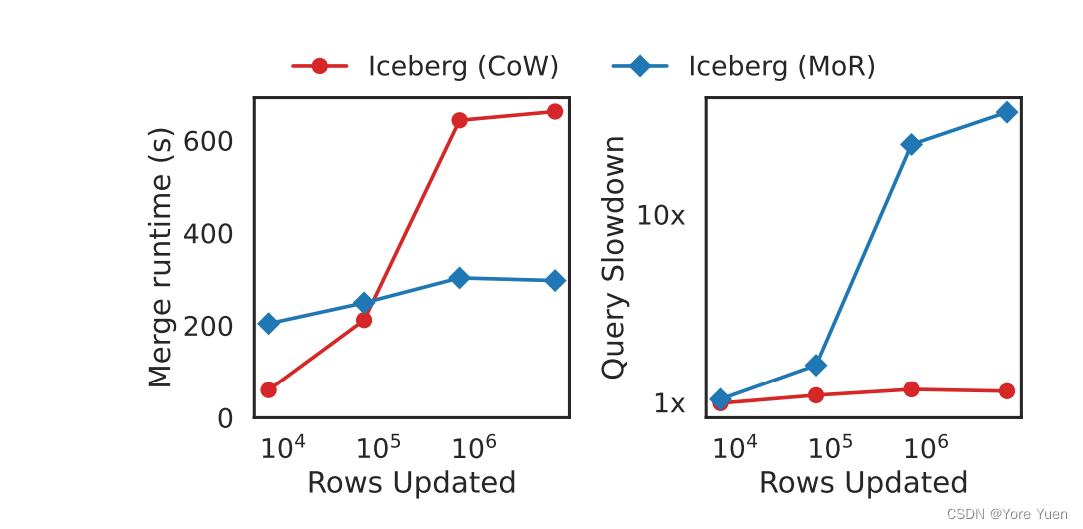

3.3.2 Merge Microbenchmark(合并微基准测试)

Generated TPC-DS refresh data does not have a configurable scale parameter. To better understand the impact of the size of a refresh on merge and query performance, we also benchmark Iceberg CoW 1.1.0 and Iceberg MoR 1.1.0 with an isolated microbenchmark. We load a synthetic table with four columns and then apply a single merge from a randomly sampled table with a configurable fraction of the base table size. In addition to the latency of the merge operation, we compare the slowdown for a query after the merge. For each merge scale evaluated, 50% of the rows are inserts while 50% are updates.

生成的TPC-DS刷新数据没有可配置的缩放参数。为了更好地理解刷新大小对合并和查询性能的影响,我们还使用一个独立的微基准测试Iceberg CoW 1.1.0和Iceberg MoR 1.1.0。我们加载一个具有四列的合成表,然后从具有基本表大小的可配置部分的随机采样表中应用单个合并。除了合并操作的延迟之外,我们还比较了减慢的合并后查询速度。对于每个评估的合并比例,50%的行是插入,而50%是更新。

Figure 3 shows results for a 100 GB benchmark. Iceberg MoR merge latency is consistently lower than that of Iceberg CoW except for the 0.0001% merge configuration (due to fixed overheads in the Iceberg MoR implementation). Iceberg MoR is 1.48× faster at the largest merge configuration (0.1%). We expect Iceberg CoW and MoR merge latency to converge for large merges approaching the size of a full file. For reads, MoR experiences large slowdowns after the merge is performed due to additional read amplification. Iceberg must combine the incremental merge files with the larger columnar files from the initial load. At about 10,000 rows, Iceberg MoR query latency exceeds that of Iceberg CoW.

图3显示了100GB基准测试的结果。除了0.0001%的合并配置(由于Iceberg MoR实现中的固定开销)外,Iceberg MoR合并延迟始终低于Iceberg CoW。在最大合并配置(0.1%)下,Iceberg MoR的速度是1.48倍。对于接近完整文件大小的大型合并,我们预计Iceberg CoW和MoR的合并延迟会收敛。对于读取,由于额外的读放大,在执行合并之后,MoR经历了大的减慢。Iceberg必须将增量合并文件与初始加载时的较大列式文件相结合。在大约10000行的情况下,Iceberg MoR查询延迟超过了Iceberg CoW。

图3:将不同大小的合并(左)到合成表中的延迟,合并后的查询延迟会相应降低(右)。合并行是50%的插入和50%的更新。

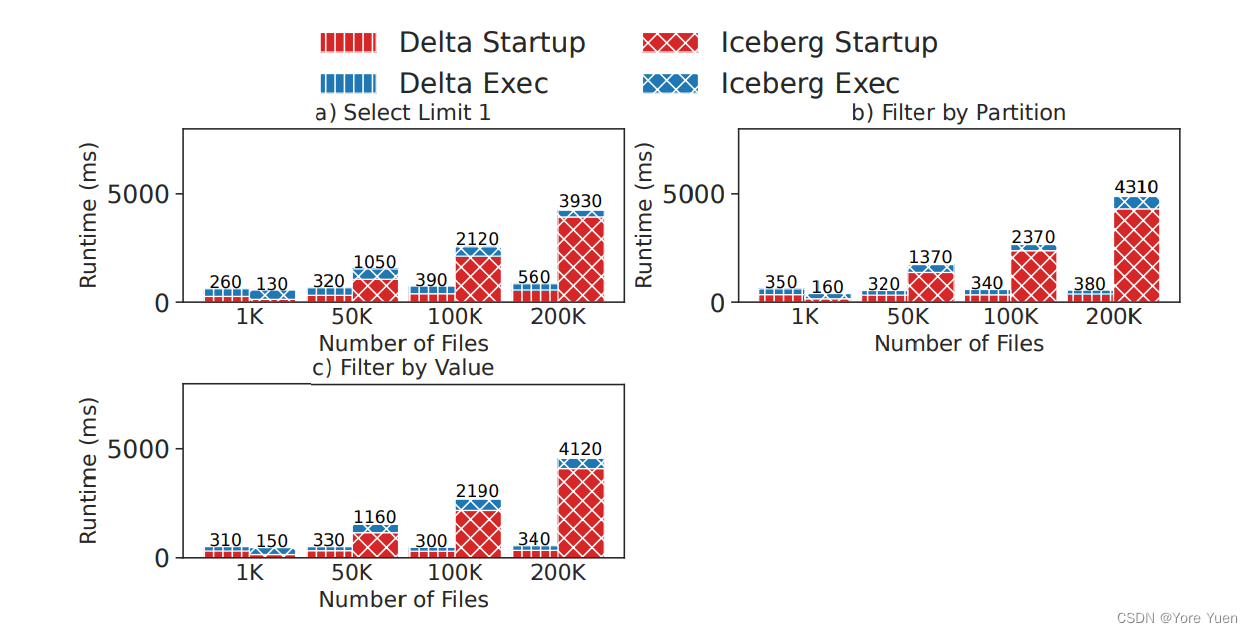

3.4 分布式元数据处理的影响

We now examine the performance impact of lakehouse metadata processing strategies on large tables stored in many files. We generate TPC-DS data (from the store_sales table) and store it in a varying number of 10 MB files (1K to 200K files, or 10 GB to 2 TB of total data) in Delta Lake and Iceberg. We choose these two systems to contrast their different metadata access strategies: Delta Lake distributes metadata processing during query planning by running it on Spark, while Iceberg runs it on a single node. To isolate the impact of metadata operations, we use three queries with high selectivity: one accessing a single row, one accessing a single partition, and one accessing only rows containing a specific value (which allows both systems to minimize the number of files scanned using zone maps). We measure both the query startup time, defined as the time elapsed between when a query is submitted and when the first data scan job begins executing, and the total query execution time. All measurements are taken from a warm start as the median of three runs. We plot the results in Figure 4.

我们现在研究湖仓元数据处理策略对存储在许多文件中的大型表的性能影响。我们生成TPC-DS数据(来自store_sales表),并将其存储在Delta Lake和Iceberg中不同数量的10 MB文件中(1K到200K文件,或10 GB到2 TB的总数据)。我们选择这两个系统来对比它们不同的元数据访问策略:Delta Lake通过在查询规划期间分发元数据处理在Spark上运行,而Iceberg则在单个节点上运行。为了隔离元数据操作的影响,我们使用了三个具有高选择性的查询:一个访问单行,一个访问单个分区,以及一个只访问包含特定值的行(这使两个系统都可以最大限度地减少使用 zone map扫描的文件数)。我们测试查询启动时间和总查询执行时间,查询启动时间定义为从提交查询到第一个数据扫描作业开始执行之间的时间。所有测试都是在一个友好的环境开始,取三次运行的中间值。我们将结果绘制在图4中。

图4:Delta Lake和Iceberg中存储在10 MB文件中的不同数据量的基本表操作的启动(包括查询计划)和查询执行时间。

For these selective queries, metadata access strategies have a large effect on performance, and are the bottleneck for larger tables. Specifically, while Iceberg’s single-node query planning performs better for smaller tables, Delta Lake’s distributed planning scales better and improves performance by 7–12× for a 200K file table.

对于这些选择性的查询,元数据访问策略对性能有很大影响,并且是较大表的瓶颈。具体来说,虽然Iceberg的单节点查询计划在较小的表中表现更好,但Delta Lake的分布式计划在200K文件表中扩展得更好,性能提高了7-12倍。

4 相关工作

To provide low-cost, directly-accessible storage, lakehouse systems build on cloud object stores and data lakes such as S3, ADLS, HDFS, and Google Cloud Storage. However, these systems provide a minimal interface based on basic primitives such as PUT, GET, and LIST. Lakehouse systems augment data lakes with advanced data management features such as ACID transactions and metadata management for efficient query optimization. There has been much prior work on building ACID transactions on weakly consistent stores. For example, Brantner et al. [25] showed how to build a transactional database on top of S3, although their focus was on supporting highly concurrent small operations (OLTP) not large analytical queries. Percolator [32] bolted ACID transactions onto BigTable using multi-version concurrency control, much like Delta Lake, Hudi and Iceberg, but otherwise used BigTable’s query executor unmodified.

为了提供低成本、可直接访问的存储,湖仓系统建立在云对象存储和数据湖之上,如S3、ADLS、HDFS和谷歌云存储。然而,这些系统提供了一个基于基本原语(如PUT、GET和LIST)的最小接口。湖仓系统通过高级数据管理功能(如ACID事务和元数据管理)来增强数据湖,以实现高效的查询优化。以前有很多关于在弱一致性存储上构建ACID事务的工作。例如,Brantner等人[25]展示了如何在S3之上构建事务数据库,尽管他们的重点是支持高度并发的小型操作(OLTP),而不是大型分析查询。Percolator[32]使用多版本并发控制将ACID事务绑定到BigTable上,就像Delta Lake、Hudi和Iceberg一样,但在其他方面未经修改地使用了BigTable的查询执行器。

Cloud data warehouses, such as Redshift and Snowflake, provide scalable management of structured data, supporting DBMS features such as transactions and query optimization with a focus on analytics. These systems typically use columnar architectures inspired by MonetDB/X100 [29] and C-Store [33]. Some of them ingest data into a specialized format that must later be reconciled with the steady-state storage format (for example, by C-Store’s tuple mover), similar to the merge-on-read strategy used by some lakehouse systems. To improve scalability, cloud data warehouses are increasingly adopting a disaggregated architecture where data resides in a cloud object store but is locally cached on database servers during query execution [34]. Hence, warehouse and lakehouse systems are converging, as both rely on low-cost object storage. However, unlike lakehouse storage formats, data warehouses do not provide directly accessible storage through an open data format.

Redshift和Snowflake等云数据仓库提供结构化数据的可扩展管理,支持事务和查询优化等DBMS功能,重点是分析。这些系统通常使用受MonetDB/X100[29]和C-Store[33]启发的列式架构。他们中的一些人将数据摄入到一种特殊的格式中,这种格式后来必须与稳态存储格式(steady-state storage)相协调(例如,通过C-Store的元组移动器),类似于一些湖仓系统使用的读时合并策略。为了提高可扩展性,云数据仓库越来越多地采用分离架构(disaggregated architecture),其中数据驻留在云对象存储中,但在查询执行期间本地缓存在数据库服务器上[34]。因此,仓库和湖仓系统正在融合,因为两者都依赖于低成本的对象存储。然而,与湖仓存储格式不同,数据仓库不通过开放数据格式提供直接可访问的存储。

5 结论和未决问题

The design of lakehouse systems involves important tradeoffs around transaction coordination, metadata storage, and data ingestion strategies that significantly effect performance. Intelligently navigating these tradeoffs is critical to efficiently executing diverse real-world workloads. In this paper, we discussed these tradeoffs in detail and proposed and evaluated an open-source benchmark suite, LHBench, for future researchers to use to study lakehouse systems. We close with several suggestions for future research:

湖仓系统的设计涉及到围绕事务协调、元数据存储和数据接收策略的重要权衡,这些策略会显著影响性能。智能地处理这些权衡对于高效地执行现实世界不同的工作负载至关重要。在本文中,我们详细讨论了这些权衡,并提出并评估了一个开源基准套件LHBench,供未来的研究人员用于研究湖仓系统。最后,我们对未来的研究提出了几点建议:

• How can lakehouse systems best balance ingest latency and query latency? Can data merges be pushed off of the critical path and done asynchronously without impacting query latency? And can systems automatically implement an optimal compaction strategy for a given workload?

• Can we use a cost model to intelligently choose between query planning strategies, using an indexed search to plan small or highly selective queries on a single node but a distributed metadata query to plan larger queries?

• Can lakehouse systems efficiently support high write QPS under concurrency? Currently, this is challenging because lakehouse systems must write to the underlying object store to update some metadata on every write query, and these systems have high latency (often >50 ms), which limits overall QPS.

- 湖仓系统如何最好地平衡摄入延迟和查询延迟?在不影响查询延迟的情况下,数据合并是否可以从关键路径中推出来并异步完成?对于给定的工作负载,系统能否自动实现最佳压缩策略?

- 我们是否可以使用成本模型在查询计划策略之间进行智能选择,使用索引搜索来计划单个节点上的小型或高度选择性的查询,而使用分布式元数据查询来计划大型查询?

- 湖仓系统能有效地支持并发下的高写QPS吗?目前,这是具有挑战性的,因为湖仓系统必须写入底层对象存储,以在每次写入查询时更新一些元数据,并且这些系统具有高延迟(通常>50ms),这限制了整体QPS。

致谢

This work was supported by NSF CISE Expeditions Award CCF-1730628, NSF CAREER grant CNS-1651570, and gifts from Amazon, Ant Financial, Astronomer, Cisco, Google, IBM, Intel, Lacework, Microsoft, Meta, Nexla, Samsung SDS, SAP, Uber, and VMWare. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

这项工作得到了NSF CISE Expeditions Award CCF-1730628、NSF CAREER grant CNS-1651570的支持,以及Amazon、蚂蚁金服、Astronomer、Cisco、Google、IBM、Intel、Lacework、微软、Meta、Nexla、Samsung SDS、SAP、Uber和VMWare的资助。本材料中表达的任何观点、发现、结论或建议都是作者的观点,并不一定反映美国国家科学基金会的观点。

参考资料

[1] 2020. Amazon Redshift Spectrum adds support for querying open source Apache Hudi and Delta Lake. https://aws.amazon.com/about-aws/whatsnew/2020/09/amazon-redshift-spectrum-adds-support-for-querying-opensource-apache-hudi-and-delta-lake/

[2] 2020. Building a Large-scale Transactional Data Lake at Uber Using Apache Hudi.https://www.uber.com/blog/apache-hudi-graduation/

[3] 2021. How to build an open cloud datalake with Delta Lake, Presto & Dataproc Metastore. https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/developers-practitioners/howbuild-open-cloud-datalake-delta-lake-presto-dataproc-metastore

[4] 2022. Apache Hudi. https://hudi.apache.org

[5] 2022. Apache Hudi Concurrency Control. https://hudi.apache.org/docs/next/concurrency_control/

[6] 2022. Apache Iceberg. https://iceberg.apache.org

[7] 2022. Apache Iceberg Isolation Levels. https://iceberg.apache.org/javadoc/0.11.0/org/apache/iceberg/IsolationLevel.html

[8] 2022. AWS EMR Hudi support. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/emr/latest/ReleaseGuide/emr-hudi.html

[9] 2022. Deletion Vectors to speed up DML operations. https://github.com/deltaio/delta/issues/1367

[10] 2022. Delta Lake Concurency Control. https://docs.databricks.com/delta/concurrency-control.html

[11] 2022. Hive: Fix concurrent transactions overwriting commits by adding hive lockheartbeats. https://github.com/apache/iceberg/pull/5036

[12] 2022. Hudi Metadata Table. https://cwiki.apache.org/confluence/pages/viewpage.action?pageId=147427331

[13] 2022. Iceberg Query Planning Performance. https://iceberg.apache.org/docs/latest/performance/

[14] 2022. Iceberg Table Spec. https://iceberg.apache.org/spec/

[15] 2022. Presto. https://prestodb.io/

[16] 2022. Resolve “Timeout waiting for connection from pool” error in Amazon EMR. https://aws.amazon.com/premiumsupport/knowledge-center/emrtimeout-connection-wait/

[17] 2022. Synapse Delta Lake support. https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/synapse-analytics/spark/apache-spark-what-is-delta-lake

[18] 2022. TPC-DS Specification Version 2.1.0. https://www.tpc.org/tpc_documents_current_versions/pdf/tpc-ds_v2.1.0.pdf

[19] Atul Adya. 1999. Weak consistency: a generalized theory and optimistic implementations for distributed transactions. Ph. D. Dissertation. MIT.

[20] Azim Afroozeh. 2020. Towards a New File Format for Big Data: SIMD Friendly Composable Compression. https://homepages.cwi.nl/~boncz/msc/2020-AzimAfroozeh.pdf

[21] Michael Armbrust, Tathagata Das, Liwen Sun, Burak Yavuz, Shixiong Zhu, Mukul Murthy, Joseph Torres, Herman van Hovell, Adrian Ionescu, Alicja Łuszczak,et al. 2020. Delta lake: high-performance ACID table storage over cloud object stores. Proceedings of the VLDB Endowment 13, 12 (2020), 3411–3424.

[22] Michael Armbrust, Ali Ghodsi, Reynold Xin, and Matei Zaharia. 2021. Lakehouse:a new generation of open platforms that unify data warehousing and advanced analytics. In Proceedings of CIDR.

[23] Edmon Begoli, Ian Goethert, and Kathryn Knight. 2021. A Lakehouse Architecture for the Management and Analysis of Heterogeneous Data for Biomedical Research and Mega-biobanks. In 2021 IEEE Big Data. 4643–4651.

[24] Alexander et al. Behm. 2022. Photon: A Fast Query Engine for Lakehouse Systems.In SIGMOD 2022. 2326–2339.

[25] Matthias Brantner, Daniela Florescu, David Graf, Donald Kossmann, and Tim Kraska. 2008. Building a Database on S3. In SIGMOD 2008. 251–264.

[26] Bogdan Vladimir Ghita, Diego G. Tomé, and Peter A. Boncz. 2020. White-box Compression: Learning and Exploiting Compact Table Representations. In CIDR.

[27] Ted Gooch. 2020. Why and How Netflix Created and Migrated to a New Table Format: Iceberg. https://www.dremio.com/subsurface/why-and-how-netflixcreated-and-migrated-to-a-new-table-format-iceberg/

[28] Maurice P. Herlihy and Jeannette M. Wing. 1990. Linearizability: A Correctness Condition for Concurrent Objects. ACM Trans. Program. Lang. Syst. 12, 3 (jul 1990), 463–492. https://doi.org/10.1145/78969.78972

[29] S Idreos, F Groffen, N Nes, S Manegold, S Mullender, and M Kersten. 2012. Monetdb: Two decades of research in column-oriented database. IEEE Data Engineering Bulletin 35, 1 (2012), 40–45.

[30] Samuel Madden, Jialin Ding, Tim Kraska, Sivaprasad Sudhir, David Cohen, Timothy Mattson, and Nesmie Tatbul. 2022. Self-Organizing Data Containers. In CIDR 2022.

[31] Raghunath Othayoth Nambiar and Meikel Poess. 2006. The Making of TPC-DS. In VLDB, Vol. 6. Citeseer, 1049–1058.

[32] Daniel Peng and Frank Dabek. 2010. Large-scale incremental processing using distributed transactions and notifications. In OSDI 2010.

[33] Mike Stonebraker, Daniel J. Abadi, Adam Batkin, Xuedong Chen, Mitch Cherniack, Miguel Ferreira, Edmond Lau, Amerson Lin, Sam Madden, Elizabeth O’Neil, Pat O’Neil, Alex Rasin, Nga Tran, and Stan Zdonik. 2005. C-Store: A Column-Oriented DBMS. In VLDB 2005. 553–564.

[34] Midhul Vuppalapati, Justin Miron, Rachit Agarwal, Dan Truong, Ashish Motivala,and Thierry Cruanes. 2020. Building An Elastic Query Engine on Disaggregated Storage. In NSDI 2020. 449–462.

716

716

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?