滑块逃脱

In this article, I would like to propose an alternative to the traditional test design style using functional programming concepts in Scala. This approach was inspired by many months of pain from maintaining dozens of failing tests and a burning desire to make them more straightforward and more comprehensible.

在本文中,我想提出一个使用Scala中的函数式编程概念的传统测试设计风格的替代方法。 这种方法的灵感来自维持数十个失败的测试所经历的数月之久的痛苦,以及使它们变得更直接和更易理解的强烈愿望。

Even though the code is in Scala, the proposed ideas are appropriate for developers and QA engineers who use languages supporting functional programming. You can find a Github link with the full solution and an example at the end of the article.

即使代码在Scala中,所提出的想法也适用于使用支持函数式编程的语言的开发人员和QA工程师。 您可以在本文末尾找到包含完整解决方案的Github链接和示例。

问题 (The problem)

If you ever had to deal with tests (doesn’t matter which ones: unit-tests, integrational or functional), they were most likely written as a set of sequential instructions. For instance:

如果您曾经不得不处理测试(与哪个测试无关:单元测试,集成测试或功能测试),它们很可能被编写为一组顺序指令。 例如:

// The following tests describe a simple internet store.

// Depending on their role, bonus amount and the order’s

// subtotal, users may receive a discount of some size.

"If user’s role is ‘customer’" - {

import TestHelper._

"And if subtotal < 250 after bonuses - no discount" in {

val db: Database = Database.forURL(TestConfig.generateNewUrl())

migrateDb(db)

insertUser(db, id = 1, name = "test", role = "customer")

insertPackage(db, id = 1, name = "test", userId = 1, status = "new")

insertPackageItems(db, id = 1, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 30)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 2, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 20)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 3, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 40)

val svc = new SomeProductionLogic(db)

val result = svc.calculatePrice(packageId = 1)

result shouldBe 90

}

"And if subtotal >= 250 after bonuses - 10% off" in {

val db: Database = Database.forURL(TestConfig.generateNewUrl())

migrateDb(db)

insertUser(db, id = 1, name = "test", role = "customer")

insertPackage(db, id = 1, name = "test", userId = 1, status = "new")

insertPackageItems(db, id = 1, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 100)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 2, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 120)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 3, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 130)

insertBonus(db, id = 1, packageId = 1, bonusAmount = 40)

val svc = new SomeProductionLogic(db)

val result = svc.calculatePrice(packageId = 1)

result shouldBe 279

}

}

"If user’s role is ‘vip’" - {/*...*/}In my experience, this way of writing tests is preferred by most developers. Our project has about a thousand tests on different levels of isolation, and all of them were written in such style until just recently. As the project grew, we began to notice severe problems and slowdowns in maintaining such tests: fixing them would take at least the same amount of time as writing production code.

以我的经验,大多数开发人员都倾向于使用这种编写测试的方式。 我们的项目有大约一千个关于不同隔离级别的测试,并且直到最近才全部以这种风格编写。 随着项目的发展,我们开始注意到严重的问题和维护此类测试的速度变慢:修复这些问题至少需要花费与编写生产代码相同的时间。

When writing new tests, we always had to come up with ways to prepare data from scratch, usually by copying and pasting steps from neighboring tests. As a result, when the application’s data model would change, the house of cards would crumble, and we would have to repair every failing test: in a worst-case scenario — by diving deep into each test and rewriting it.

在编写新测试时,我们通常必须想出从头开始准备数据的方法,通常是通过复制和粘贴相邻测试中的步骤。 结果,当应用程序的数据模型发生变化时,卡的空间就会崩溃,我们将不得不修复所有失败的测试:在最坏的情况下,请深入研究每个测试并重写它。

When a test would fail “honestly” — i.e. because of an actual bug in business logic — understanding what went wrong without debugging was impossible. Because the tests were so difficult to understand, nobody had the full knowledge always at hand on how the system is supposed to behave.

当测试“诚实地”失败时(即由于业务逻辑中的实际错误),就不可能了解没有调试就出了什么问题。 由于测试是如此难以理解,因此没有人总是拥有关于系统应如何运行的全面知识。

All of this pain, in my opinion, is a symptom of such test design’s two deeper problems:

我认为,所有这些痛苦是这种测试设计的两个更深层问题的症状:

- There is no clear and practical structure for tests. Every test is a unique snowflake. Lack of structure leads to verbosity, which eats up much time and demotivates. Insignificant details distract from what’s most important — the requirement that the test asserts. Copying and pasting become the primary approach to writing new test cases. 没有明确而实用的测试结构。 每个测试都是独一无二的雪花。 缺乏结构会导致冗长,这会浪费大量时间并使您失去动力。 无关紧要的细节分散了最重要的内容—测试所确定的要求。 复制和粘贴成为编写新测试用例的主要方法。

- Tests don’t help developers in localizing defects; they only signal there is a problem of some kind. To understand the state in which the test gets run, you have to plot it in your head or use a debugger. 测试无法帮助开发人员定位缺陷。 他们只表示存在某种问题。 要了解测试运行的状态,您必须将其绘制在脑海中或使用调试器。

造型 (Modeling)

Can we do better? (Spoiler alert: we can.) Let’s consider what kind of structure this test may have.

我们可以做得更好吗? (扰流板警报:我们可以。)让我们考虑一下该测试可能具有的结构。

val db: Database = Database.forURL(TestConfig.generateNewUrl())

migrateDb(db)

insertUser(db, id = 1, name = "test", role = "customer")

insertPackage(db, id = 1, name = "test", userId = 1, status = "new")

insertPackageItems(db, id = 1, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 30)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 2, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 20)

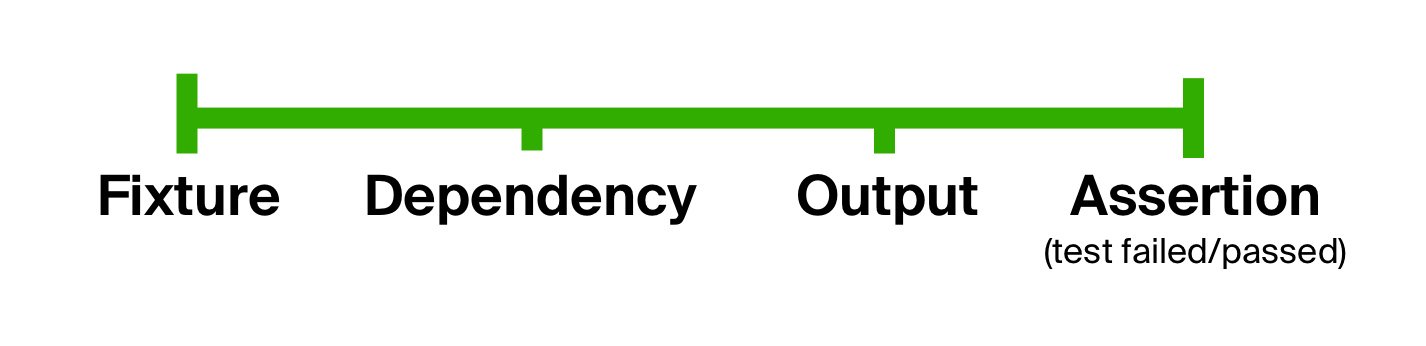

insertPackageItems(db, id = 3, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 40)As a rule of thumb, the code under test expects some explicit parameters (identifiers, sizes, amounts, filters, to name a few), as well as some external data (from a database, queue or some other real-world service). For our test to run reliably, it needs a fixture — a state to put the system, the data providers, or both in.

根据经验,要测试的代码需要一些明确的参数(标识符,大小,数量,过滤器,仅举几例)以及一些外部数据(来自数据库,队列或某些其他实际服务)。 为了使测试可靠地运行,它需要一个固定装置 -一种将系统和/或数据提供者放入其中的状态。

With this fixture, we prepare a dependency to initialize the code under test — fill a database, create a queue of a particular type, etc.

有了这个工具,我们准备了一个依赖项来初始化被测代码—填充数据库,创建特定类型的队列等。

val svc = new SomeProductionLogic(db)

val result = svc.calculatePrice(packageId = 1)After running the code under test on some input parameters, we receive an output — both explicit (returned by the code under test) and implicit (the changes in the state).

在某些输入参数上运行被测代码之后,我们会收到一个输出 -显式(由被测代码返回)和隐式(状态变化)。

result shouldBe 90Finally, we check that the output is as expected, finishing the test with one or more assertions.

最后,我们检查输出是否符合预期,并使用一个或多个断言完成测试。

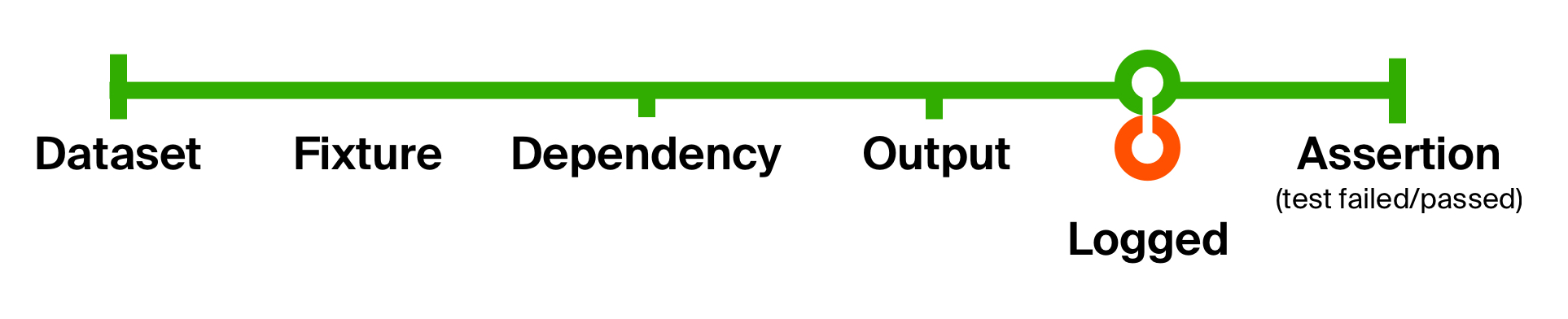

One can conclude that tests generally consist of the same stages: input preparation, code execution, and result assertion. We can use this fact to get rid of the first problem of our tests, i.e. overly liberal form, by explicitly splitting a test’s body into stages. Such an idea is not new, as it can be seen in BDD-style (behavior-driven development) tests.

可以得出结论,测试通常由相同的阶段组成:输入准备,代码执行和结果声明。 通过将测试的主体明确地划分为多个阶段,我们可以利用这一事实摆脱测试的第一个问题 ,即过于自由的形式。 在BDD样式( 行为驱动的开发 )测试中可以看到这种想法并不新鲜。

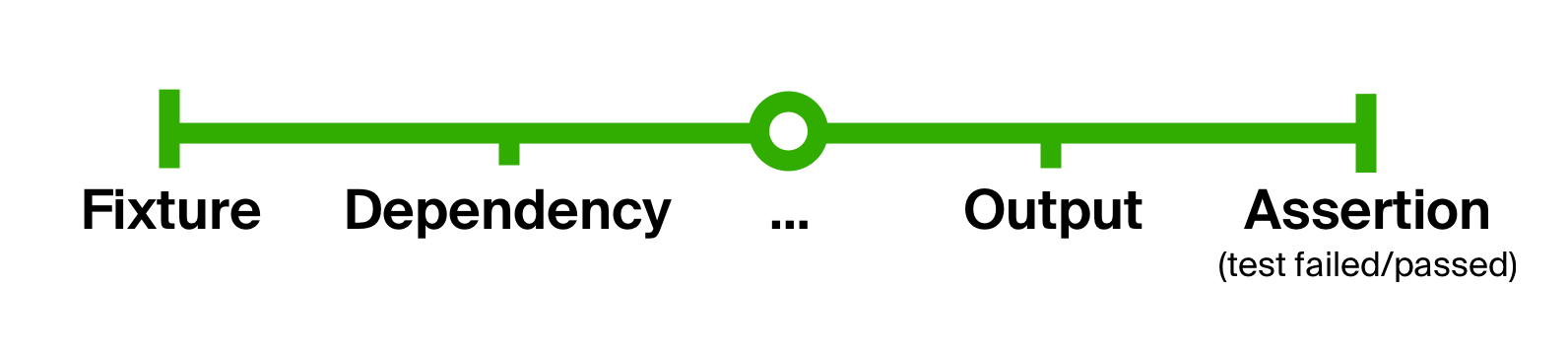

What about extendability? Any step of the testing process may, in turn, contain any amount of intermediate ones. For instance, we could take a big and complicated step, like building a fixture, and split it into several, chained one after another. This way, the testing process can be infinitely extendable, but ultimately always consisting of the same few general steps.

扩展性又如何呢? 测试过程的任何步骤都可以包含任意数量的中间步骤。 例如,我们可以迈出一个大而复杂的步骤,例如构建一个灯具,然后将其拆分为几个,一个接一个地链接。 这样,测试过程可以无限扩展,但最终总是由相同的几个常规步骤组成。

运行测试 (Running tests)

Let’s try to implement the idea of splitting the test into stages, but first, we should determine what kind of result we would like to see.

让我们尝试实现将测试分为多个阶段的想法,但是首先,我们应该确定我们希望看到什么样的结果。

Overall, we would like writing and maintaining tests to become less labor-intensive and more pleasant. The fewer explicit non-unique instructions a test has, the fewer changes would have to be made into it after changing contracts or refactoring, and the less time it would take to read the test. Test’s design should promote reusing of common code snippets and discourage mindless copying and pasting. It would also be nice if the tests would have a unified form. Predictability improves readability and saves time. For example, imagine how much more time would it take aspiring scientists to learn all the formulas if textbooks would have them written freely in common language as opposed to math.

总体而言,我们希望编写和维护测试变得更省力,更愉快。 测试具有的显式非唯一指令越少,在更改合同或重构后必须对它进行的更改就越少,并且读取测试所需的时间也就越少。 测试的设计应促进通用代码段的重用,并避免盲目的复制和粘贴。 如果测试具有统一的形式,那也很好。 可预测性提高了可读性并节省了时间。 例如,想象一下,如果有教科书的科学家能够用通用语言而不是数学自由地编写它们,那么花更多的时间来学习所有公式。

Thus, our goal is to hide anything distracting and unnecessary, leaving only what is critically important for understanding: what is being tested, what are the expected inputs and outputs.

因此,我们的目标是隐藏任何分散注意力和不必要的内容,仅保留对于理解至关重要的内容:正在测试的内容,预期的输入和输出。

Let’s get back to our model of the test’s structure.

让我们回到测试结构的模型。

Technically, every step of it can be represented by a data type, and every transition — by a function. To get from the initial data type to the final one is possible by applying each function to the result of the previous one. In other words, by using function composition of data preparation (let’s call it prepare), code execution (execute) and checking of the expected result (check). The input for this composition would be the very first step — the fixture. Let’s call the resulting higher-order function the test lifecycle function.

从技术上讲,它的每一步都可以由数据类型来表示,而每个过渡都可以由函数来表示。 通过将每个函数应用于上一个函数的结果,可以从初始数据类型获取最后一个数据类型。 换句话说,通过使用数据准备的函数组成(我们称其为prepare ),代码执行( execute )和检查预期结果( check )。 此合成的输入将是第一步-夹具。 让我们将生成的高阶函数称为测试生命周期函数 。

测试生命周期功能 (Test lifecycle function)

def runTestCycle[FX, DEP, OUT, F[_]](

fixture: FX,

prepare: FX => DEP,

execute: DEP => OUT,

check: OUT => F[Assertion]

): F[Assertion] =

// In Scala instead of writing check(execute(prepare(fixture)))

// one can use a more readable version using the andThen function:

(prepare andThen execute andThen check) (fixture)A question arises, where do these certain functions come from? Well, as for data preparation, there’s only a limited amount of ways to do so — filling a database, mocking, etc. Thus, it’s handy to write specialized variants of the prepare function shared across all tests. As a result, it would be easier to make specialized test lifecycle functions for every case, which would conceal concrete implementations of data preparation. Since code execution and assertions are more or less unique for each test (or group of tests), execute and check have to be written each time explicitly.

出现一个问题,这些特定功能从何而来? 好的,对于数据准备,只有有限的方法可以做到—填充数据库,模拟等。因此, prepare在所有测试中共享的prepare函数的专用变体很方便。 结果,针对每种情况进行专门的测试生命周期功能将变得更加容易,这将隐藏数据准备的具体实现。 由于代码执行和断言在每个测试(或一组测试)中或多或少是唯一的,因此每次必须显式编写execute和check 。

适用于数据库集成测试的测试生命周期功能 (Test lifecycle function adapted for intergration testing on a DB)

// Sets up the fixture — implemented separately

def prepareDatabase[DB](db: Database): DbFixture => DB

def testInDb[DB, OUT](

fixture: DbFixture,

execute: DB => OUT,

check: OUT => Future[Assertion],

db: Database = getDatabaseHandleFromSomewhere(),

): Future[Assertion] =

runTestCycle(fixture, prepareDatabase(db), execute, check)By delegating all the administrative nuances to the test lifecycle function, we get the ability to extend the testing process without touching any given test. By utilizing function composition, we can interfere at any step of the process and extract or add data.

通过将所有管理上的细微差别委派给测试生命周期功能,我们可以扩展测试过程而无需进行任何给定的测试。 通过利用功能组合,我们可以干预过程的任何步骤并提取或添加数据。

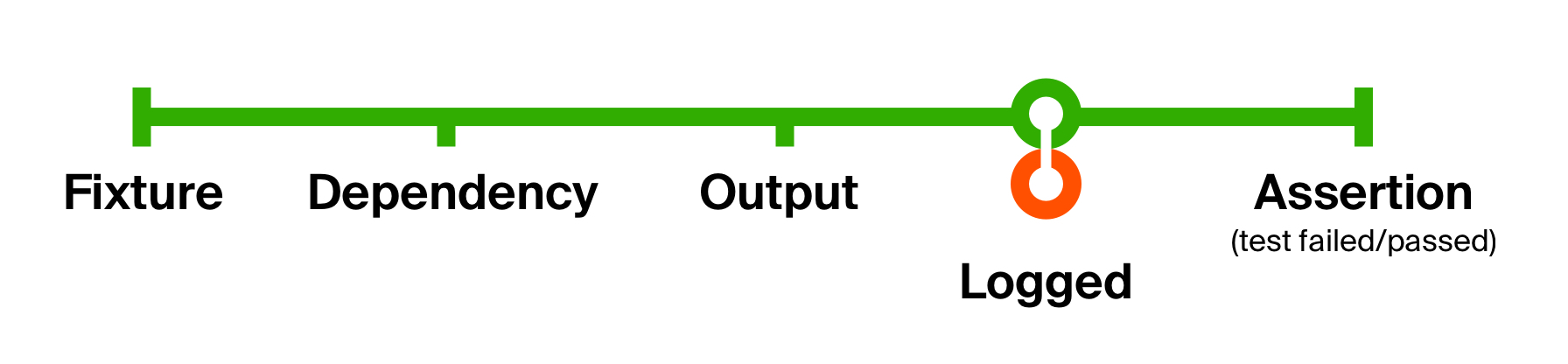

To better illustrate the capabilities of such an approach, let’s solve the second problem of our initial test — the lack of supplemental information for pinpointing problems. Let’s add logging of whatever code execution has returned. Our logging won’t change the data type; it only produces a side-effect — outputting a message to console. After the side-effect, we return it as is.

为了更好地说明这种方法的功能,让我们解决初始测试的第二个问题 -缺少用于查明问题的补充信息。 让我们添加记录返回的代码执行情况。 我们的日志记录不会更改数据类型。 它只会产生副作用 -将消息输出到控制台。 产生副作用后,我们将其照原样返回。

使用日志记录测试生命周期功能 (Test lifecycle function with logging)

def logged[T](implicit loggedT: Logged[T]): T => T =

(that: T) => {

// By passing an instance of the Logged typeclass for T as an argument,

// we get an ability to “add” behavior log() to the abstract “that” member.

// More on typeclasses later on.

loggedT.log(that) // We could even do: that.log()

that // The object gets returned unaltered

}

def runTestCycle[FX, DEP, OUT, F[_]](

fixture: FX,

prepare: FX => DEP,

execute: DEP => OUT,

check: OUT => F[Assertion]

)(implicit loggedOut: Logged[OUT]): F[Assertion] =

// Insert logged right after receiving the result - after execute()

(prepare andThen execute andThen logged andThen check) (fixture)With this simple change, we have added logging of the executed code’s output in every test. The advantage of such small functions is that they’re easy to understand, compose, and get rid of when needed.

通过此简单更改,我们在每个测试中都添加了对执行代码输出的记录。 如此小的函数的优点是易于理解,编写和在需要时摆脱它们。

As a result, our test now looks like this:

结果,我们的测试现在看起来像这样:

val fixture: SomeMagicalFixture = ??? // Comes from somewhere else

def runProductionCode(id: Int): Database => Double =

(db: Database) => new SomeProductionLogic(db).calculatePrice(id)

def checkResult(expected: Double): Double => Future[Assertion] =

(result: Double) => result shouldBe expected

// The creation and filling of Database is hidden in testInDb

"If user’s role is ‘customer’" in testInDb(

state = fixture,

execute = runProductionCode(id = 1),

check = checkResult(90)

)The test’s body became concise, the fixture and the checks can be reused in other tests, and we don’t prepare the database manually anywhere anymore. Only one tiny problem remains...

测试的主体变得简洁,夹具和检查可以在其他测试中重复使用,我们不再在任何地方手动准备数据库。 仍然只有一个小问题...

治具准备 (Fixture preparation)

In the code above we were working under an assumption that the fixture would be given to us from somewhere. Since data is the critical ingredient of maintainable and straightforward tests, we have to touch on how to make them easily.

在上面的代码中,我们假设将固定装置从某个地方提供给我们。 由于数据是可维护和直接测试的关键要素,因此我们必须探讨如何轻松进行测试。

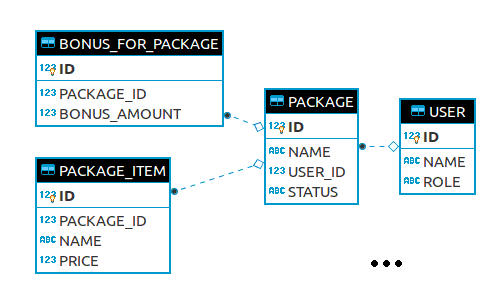

Suppose our store under test has a typical medium-sized relational database (for the sake of simplicity, in this example it has only 4 tables, but in reality, it can have hundreds). Some tables have referential data, some — business data, and all of that can be logically grouped into one or more complex entities. Relations are linked together with foreign keys, to create a Bonus, a Package is required, which in turn needs a User, and so on.

假设我们的被测试商店有一个典型的中型关系数据库(为简单起见,在此示例中,它只有4个表,但实际上可以有数百个表)。 有些表具有参考数据,有些表具有业务数据,并且所有这些都可以在逻辑上分组为一个或多个复杂实体。 关系与外键链接在一起,以创建Bonus ,需要Package ,而Package则需要User ,依此类推。

Workarounds and hacks only lead to data inconsistency and, as a result, to hours upon hours of debugging. For this reason, we are not making changes to the schema in any way.

解决方法和黑客攻击只会导致数据不一致,结果导致调试工作数小时。 因此,我们不会以任何方式对架构进行更改。

We could use some production methods to fill it, but even under shallow scrutiny, this raises a lot of difficult questions. What will prepare data in tests for that production code? Would we have to rewrite the tests if that code’s contract changes? What if the data comes from somewhere else entirely, and there are no methods to use? How many requests would it take to create an entity that depends on many others?

我们可以使用一些生产方法来填充它,但是即使在经过严格审查的情况下,这也提出了许多难题。 测试中将为该生产代码准备哪些数据? 如果该代码的合同发生更改,我们是否必须重写测试? 如果数据完全来自其他地方怎么办? 创建依赖于许多其他实体的实体需要多少个请求?

在初始测试中填写数据库 (Database filling in the initial test)

insertUser(db, id = 1, name = "test", role = "customer")

insertPackage(db, id = 1, name = "test", userId = 1, status = "new")

insertPackageItems(db, id = 1, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 30)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 2, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 20)

insertPackageItems(db, id = 3, packageId = 1, name = "test", price = 40)Scattered helper methods, like those in our very first example, are the same issue under a different guise. They put the responsibility of managing dependencies upon ourselves which we’re trying to avoid.

像我们第一个示例中那样,分散的辅助方法在不同的表述下是相同的问题。 他们将管理依赖关系的责任置于我们要避免的自我上。

Ideally, we would like some data structure that would present the whole system’s state at just a glance. A right candidate would be a table (or a dataset, like in PHP or Python) that would have nothing extra but fields critical for the business logic. If it changes, maintaining the tests would be easy: we merely change the fields in the dataset. Example:

理想情况下,我们希望某些数据结构能够一目了然地显示整个系统的状态。 合适的人选是表(或数据集 ,如PHP或Python),除了对业务逻辑至关重要的字段外,没有其他任何东西。 如果发生变化,维护测试将很容易:我们只需更改数据集中的字段即可。 例:

val dataTable: Seq[DataRow] = Table(

("Package ID", "Customer's role", "Item prices", "Bonus value", "Expected final price")

, (1, "customer", Vector(40, 20, 30) , Vector.empty , 90.0)

, (2, "customer", Vector(250) , Vector.empty , 225.0)

, (3, "customer", Vector(100, 120, 30) , Vector(40) , 210.0)

, (4, "customer", Vector(100, 120, 30, 100) , Vector(20, 20) , 279.0)

, (5, "vip" , Vector(100, 120, 30, 100, 50), Vector(10, 20, 10), 252.0)

)

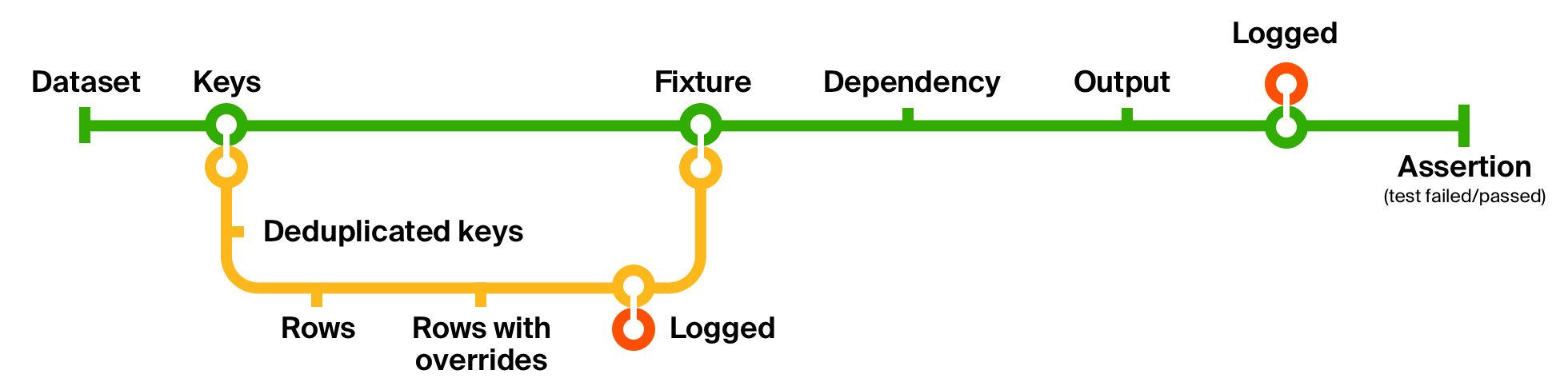

From our table, we create keys — entity links by ID. If an entity depends on another, a key for that other entity also gets created. It may so happen that two different entities create a dependency with the same ID, which can lead to a primary key violation. However, at this stage it’s incredibly cheap to deduplicate keys — since all they contain are IDs, we can put them in a collection that does deduplication for us, for example, a Set. If that turns out insufficient, we can always implement smarter deduplication as a separate function and compose it into the test lifecycle function.

在表中,我们创建键 -按ID的实体链接。 如果一个实体依赖于另一个实体,则还将创建该另一个实体的密钥。 两个不同的实体可能会创建具有相同ID的依赖关系,这可能会导致主键冲突 。 但是,在此阶段,对重复项进行重复数据删除非常便宜-因为它们包含的所有都是ID,我们可以将它们放入为我们进行重复数据删除的集合中,例如Set 。 如果结果不足,我们可以始终将更智能的重复数据删除实现为单独的功能,并将其组合到测试生命周期功能中。

按键(示例) (Keys (example))

sealed trait Key

case class PackageKey(id: Int, userId: Int) extends Key

case class PackageItemKey(id: Int, packageId: Int) extends Key

case class UserKey(id: Int) extends Key

case class BonusKey(id: Int, packageId: Int) extends KeyGenerating fake data for fields (e.g., names) is delegated to a separate class. Afterward, by using that class and conversion rules for keys, we get the Row objects intended for insertion into the database.

为字段(例如名称)生成伪造数据被委派给单独的类。 然后,通过使用该类和键的转换规则,我们获得了打算插入数据库的Row对象。

行(示例) (Rows (example))

object SampleData {

def name: String = "test name"

def role: String = "customer"

def price: Int = 1000

def bonusAmount: Int = 0

def status: String = "new"

}

sealed trait Row

case class PackageRow(id: Int, name: String, userId: Int, status: String) extends Row

case class PackageItemRow(id: Int, packageId: Int, name: String, price: Int) extends Row

case class UserRow(id: Int, name: String, role: String) extends Row

case class BonusRow(id: Int, packageId: Int, bonusAmount: Int) extends RowThe fake data is usually not enough, so we need a way to override specific fields. Luckily, lenses are just what we need — we can use them to iterate over all created rows and change only the fields we need. Since lenses are functions in disguise, we can compose them as usual, which is their strongest point.

伪造数据通常是不够的,因此我们需要一种方法来覆盖特定字段。 幸运的是, 镜头正是我们需要的-我们可以使用它们遍历所有已创建的行并仅更改我们需要的字段。 由于镜头是变相的功能,因此我们可以照常构图,这是它们的强项。

镜头(示例) (Lense (example))

def changeUserRole(userId: Int, newRole: String): Set[Row] => Set[Row] =

(rows: Set[Row]) =>

rows.modifyAll(_.each.when[UserRow])

.using(r => if (r.id == userId) r.modify(_.role).setTo(newRole) else r)Thanks to composition, we can apply different optimizations and improvements inside the process: for example, we could group rows by the table to insert them with a single INSERT to reduce test execution time or log the database’s entire state.

多亏了组合,我们可以在流程中进行不同的优化和改进:例如,我们可以按表对行进行分组,以使用单个INSERT以减少测试执行时间或记录数据库的整个状态。

夹具准备功能 (Fixture preparation function)

def makeFixture[STATE, FX, ROW, F[_]](

state: STATE,

applyOverrides: F[ROW] => F[ROW] = x => x

): FX =

(extractKeys andThen

deduplicateKeys andThen

enrichWithSampleData andThen

applyOverrides andThen

logged andThen

buildFixture) (state)Finally, the whole thing provides us with a fixture. In the test itself, nothing extra is shown, except for the initial dataset — all the details are hidden by function composition.

最后,整个过程为我们提供了解决方案。 在测试本身中,除了初始数据集之外,没有显示任何其他内容-所有详细信息都由函数组成隐藏。

Our test suite now looks like this:

现在,我们的测试套件如下所示:

val dataTable: Seq[DataRow] = Table(

("Package ID", "Customer's role", "Item prices", "Bonus value", "Expected final price")

, (1, "customer", Vector(40, 20, 30) , Vector.empty , 90.0)

, (2, "customer", Vector(250) , Vector.empty , 225.0)

, (3, "customer", Vector(100, 120, 30) , Vector(40) , 210.0)

, (4, "customer", Vector(100, 120, 30, 100) , Vector(20, 20) , 279.0)

, (5, "vip" , Vector(100, 120, 30, 100, 50), Vector(10, 20, 10), 252.0)

)

"If the buyer's role is" - {

"a customer" - {

"And the total price of items" - {

"< 250 after applying bonuses - no discount" - {

"(case: no bonuses)" in calculatePriceFor(dataTable, 1)

"(case: has bonuses)" in calculatePriceFor(dataTable, 3)

}

">= 250 after applying bonuses" - {

"If there are no bonuses - 10% off on the subtotal" in

calculatePriceFor(dataTable, 2)

"If there are bonuses - 10% off on the subtotal after applying bonuses" in

calculatePriceFor(dataTable, 4)

}

}

}

"a vip - then they get a 20% off before applying bonuses and then all the other rules apply" in

calculatePriceFor(dataTable, 5)

}And the helper code:

和帮助程序代码:

辅助程式码 (Helper code)

// Reusable test’s body

def calculatePriceFor(table: Seq[DataRow], idx: Int) =

testInDb(

state = makeState(table.row(idx)),

execute = runProductionCode(table.row(idx)._1),

check = checkResult(table.row(idx)._5)

)

def makeState(row: DataRow): Logger => DbFixture = {

val items: Map[Int, Int] = ((1 to row._3.length) zip row._3).toMap

val bonuses: Map[Int, Int] = ((1 to row._4.length) zip row._4).toMap

MyFixtures.makeFixture(

state = PackageRelationships

.minimal(id = row._1, userId = 1)

.withItems(items.keys)

.withBonuses(bonuses.keys),

overrides = changeRole(userId = 1, newRole = row._2) andThen

items.map { case (id, newPrice) => changePrice(id, newPrice) }.foldPls andThen

bonuses.map { case (id, newBonus) => changeBonus(id, newBonus) }.foldPls

)

}

def runProductionCode(id: Int): Database => Double =

(db: Database) => new SomeProductionLogic(db).calculatePrice(id)

def checkResult(expected: Double): Double => Future[Assertion] =

(result: Double) => result shouldBe expectedAdding new test cases into the table is a trivial task that lets us concentrate on covering more fringe cases and not on writing boilerplate code.

在表中添加新的测试用例是一项琐碎的任务,它使我们可以专注于覆盖更多的边缘用例,而不是编写样板代码。

在不同项目上重复使用夹具准备 (Reusing fixture preparation on different projects)

Okay, so we wrote a whole lot of code to prepare fixtures in one specific project, spending quite some time in the process. What if we have several projects? Are we doomed to reinvent the whole thing from scratch every time?

好的,所以我们写了很多代码来准备在一个特定项目中的灯具,在过程中花费了很多时间。 如果我们有几个项目怎么办? 我们是否注定每次都会从头开始彻底改造整个事情?

We can abstract the fixture preparation over a concrete domain model. In the world of functional programming, there is a concept of typeclasses. Without getting deep into details, they’re not like classes in OOP, but more like interfaces in that they define a certain behavior of some group of types. The fundamental difference is that they’re not inherited but rather instantiated like variables. However, similar to inheritance, the resolving of typeclass instances happens at compile time. In this sense, typeclasses can be grasped like extension methods from Kotlin and C#.

我们可以在具体的领域模型上抽象出夹具的准备。 在函数式编程世界中,有一个类型类的概念。 在不深入细节的情况下,它们不像OOP中的类,而是更像接口,因为它们定义了某些类型组的特定行为。 根本的区别是它们不是继承的,而是像变量一样实例化的。 但是,类似于继承,类型类实例的解析发生在编译时 。 从这种意义上讲,可以像Kotlin和C#的 扩展方法一样掌握类型类。

To log an object, we don’t need to know what’s inside, what fields and methods it has. All we care about is it having a behavior log() with a particular signature. Extending every single class with a Logged interface would be extremely tedious and even then not possible in many cases — for example, for libraries or standard classes. With typeclasses, this is much easier. We can create an instance of a typeclass called Logged, for example, for a fixture to log it in a human-readable format. For everything else that doesn’t have an instance of Logged we can provide a fallback: an instance for type Any that uses a standard method toString() to log every object in their internal representation for free.

要记录一个对象,我们不需要知道里面有什么,有什么字段和方法。 我们只关心具有特定签名的行为log() 。 用Logged接口扩展每个类非常繁琐,即使在很多情况下也是如此(例如,对于库或标准类)。 使用类型类,这要容易得多。 例如,我们可以创建一个称为Logged的类型类的实例,以便灯具将其记录为人类可读的格式。 对于没有Logged实例的所有其他内容,我们可以提供一个后备: Any类型的实例,该实例使用标准方法toString()免费记录其内部表示形式中的每个对象。

Logged类型类及其实例的示例 (An example of the Logged typeclass and its instances)

trait Logged[A] {

def log(a: A)(implicit logger: Logger): A

}

// For all Futures

implicit def futureLogged[T]: Logged[Future[T]] = new Logged[Future[T]] {

override def log(futureT: Future[T])(implicit logger: Logger): Future[T] = {

futureT.map { t =>

// map on a Future lets us modify its result after it finishes

logger.info(t.toString())

t

}

}

}

// Fallback in case there are no suitable implicits in scope

implicit def anyNoLogged[T]: Logged[T] = new Logged[T] {

override def log(t: T)(implicit logger: Logger): T = {

logger.info(t.toString())

t

}

}Besides logging, we can use this approach throughout the whole process of making fixtures. Our solution proposes an abstract way to make database fixtures and a set of typeclasses to go with it. It’s the project using the solution’s responsibility to implement the instances of these typeclasses for the whole thing to work.

除了记录之外,我们可以在制作夹具的整个过程中使用这种方法。 我们的解决方案提出了一种抽象的方法来制作数据库装置和一组与此相关的类型类。 这是项目使用解决方案的责任来实现这些类型类的实例以使整个工作正常进行的过程。

// Fixture preparation function

def makeFixture[STATE, FX, ROW, F[_]](

state: STATE,

applyOverrides: F[ROW] => F[ROW] = x => x

): FX =

(extractKeys andThen

deduplicateKeys andThen

enrichWithSampleData andThen

applyOverrides andThen

logged andThen

buildFixture) (state)

override def extractKeys(implicit toKeys: ToKeys[DbState]): DbState => Set[Key] =

(db: DbState) => db.toKeys()

override def enrichWithSampleData(implicit enrich: Enrich[Key]): Key => Set[Row] =

(key: Key) => key.enrich()

override def buildFixture(implicit insert: Insertable[Set[Row]]): Set[Row] => DbFixture =

(rows: Set[Row]) => rows.insert()

// Behavior of splitting something (e.g. a dataset) into keys

trait ToKeys[A] {

def toKeys(a: A): Set[Key] // Something => Set[Key]

}

// ...converting keys into rows

trait Enrich[A] {

def enrich(a: A): Set[Row] // Set[Key] => Set[Row]

}

// ...and inserting rows into the database

trait Insertable[A] {

def insert(a: A): DbFixture // Set[Row] => DbFixture

}

// To be implemented in our project (see the example at the end of the article)

implicit val toKeys: ToKeys[DbState] = ???

implicit val enrich: Enrich[Key] = ???

implicit val insert: Insertable[Set[Row]] = ???When designing this fixture preparation tool, I used the SOLID principles as a compass for making sure it’s maintainable and extendable:

在设计此夹具准备工具时,我使用SOLID原理作为指南针,以确保其可维护和可扩展:

The Single Responsibility Principle: each typeclass describes one and only one behavior of a type.

单一责任原则 :每个类型类仅描述一种类型的一种行为。

The Open/Closed Principle: we don’t modify any of the production classes; instead, we extend them with instances of typeclasses.

开放/封闭原则 :我们不修改任何生产类别; 相反,我们使用类型类的实例对其进行扩展。

The Liskov Substitution Principle doesn’t apply here since we don’t use inheritance.

Liskov替代原则在这里不适用,因为我们不使用继承。

The Interface Segregation Principle: we use many specialized typeclasses as opposed to a global one.

接口隔离原则 :我们使用许多专门的类型类,而不是全局的类。

The Dependency Inversion Principle: the fixture preparation function doesn’t depend on concrete types, but rather on abstract typeclasses.

依赖倒置原则 :夹具准备功能不依赖于具体类型,而是依赖于抽象类型类。

After making sure that all of the principles are satisfied, we may safely assume that our solution is maintainable and extendable enough to be used in different projects.

在确保满足所有原则之后,我们可以安全地假定我们的解决方案是可维护和可扩展的,足以在不同项目中使用。

After writing the test lifecycle function and the solution for fixture preparation, which is also independent of a concrete domain model on any given application, we’re all set to improve all of the remaining tests.

在编写了测试生命周期功能和夹具准备解决方案(也与任何给定应用程序上的具体领域模型无关)之后,我们将着手改善所有其余测试。

底线 (Bottom line)

We have switched from the traditional (step-by-step) test design style to functional. Step-by-step style is useful early on and in smaller-sized projects, because it doesn’t restrict developers and doesn’t require any specialized knowledge. However, when the amount of tests becomes too large, such a style tends to fall off. Writing tests in the functional style probably won’t solve all your testing problems, but it might significantly improve scaling and maintaining tests in projects, where there’s hundreds or thousands of them. Tests that are written in the functional style turn out to be more concise and focused on the essential things (such as data, code under test, and the expected result), not on the intermediate steps.

我们已经从传统的(逐步的)测试设计风格转变为实用的。 分步样式在早期和较小的项目中很有用,因为它不会限制开发人员,也不需要任何专业知识。 但是,当测试量太大时,这种样式倾向于下降。 以功能风格编写测试可能无法解决您所有的测试问题,但是它可能会显着改善在有成百上千个项目的项目中的扩展和维护测试。 用功能样式编写的测试变得更加简洁,并且侧重于基本内容(例如数据,被测代码和预期结果),而不是中间步骤。

Moreover, we have explored just how powerful can function composition and typeclasses be in functional programming. With their help, it’s quite simple to design solutions with extendability and reusability in mind.

此外,我们还探讨了函数组合和类型类在函数式编程中的功能有多强大。 在他们的帮助下,设计具有可扩展性和可重用性的解决方案非常简单。

Since adopting the style several months ago, our team had to spend some effort adapting, but in the end, we enjoyed the result. New tests get written faster, logs make life much more comfortable, and datasets are handy to check whenever there are questions about some logic’s intricacies. Our team aims to switch all of the tests to this new style gradually.

自几个月前采用该样式以来,我们的团队不得不花费一些精力进行调整,但最终,我们享受了结果。 新测试的编写速度更快,日志使生活更加舒适,并且只要对某些逻辑的复杂性有疑问,就可以方便地检查数据集。 我们的团队旨在逐步将所有测试转换为这种新样式。

Link to the solution and a complete example can be found here: Github. Have fun with your testing!

链接到该解决方案,并且可以在这里找到完整的示例: Github 。 祝您测试愉快!

滑块逃脱

本文介绍了一种使用Scala和函数式编程概念的新型测试设计方法,旨在解决传统测试设计中的问题,如冗长、难以理解和维护。通过将测试过程分解为阶段,引入函数组合和类型类,实现了测试的简化和标准化,提高了测试的可读性和可维护性。

本文介绍了一种使用Scala和函数式编程概念的新型测试设计方法,旨在解决传统测试设计中的问题,如冗长、难以理解和维护。通过将测试过程分解为阶段,引入函数组合和类型类,实现了测试的简化和标准化,提高了测试的可读性和可维护性。

1935

1935

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?