In this present world that abounds with different cultures, language remains the closest and most telling gateway to learning the heart and soul of a cultural group. More than being merely a means to communicate, language has an intrinsic relationship with the very nature of culture such that it influences and reflects everything there is to a group's identity, beliefs, and background. This blog explains how learning the language of a culture group is the key to a rich understanding of its culture on seven broad dimensions.

1. Creation of values: The Linguistic Mould of Cultural Values

Language is the prime reason for the creation of the values of a cultural group. Sapir - Whorf hypothesis (Whorf, 1956) states that the language dictates our perception and interpretation of the world, and hence, shapes our value systems. For example, in Japanese, the intricate honorific system is an elaborate expression of cultural values of respect, hierarchy, and harmony of groups (Brown & Levinson, 1987). The terms and phrases used to address different social statuses and relationships are very sensitive, emphasizing the important fact of maintaining the correct social order. By contrast, English phrases like "pursue your dreams" and "be true to yourself" both express Western values of individualism and self-expression. Unlearned, these highly internalized systems of values embedded in patterns of language can often remain hidden or misinterpreted.

2. Shaping social systems: Language as the Master Plan of Social Systems

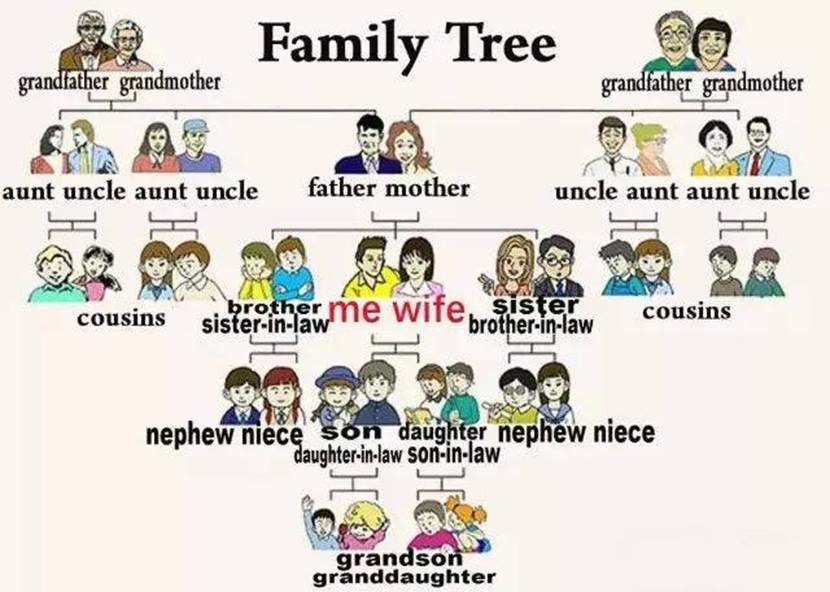

Language is the master plan for social systems within a culture group. As Foucault (1972) has argued, language cannot be separated from power relations and social norms. In Mandarin Chinese, the complex kinship terms "叔叔" (father's younger brother), "姑姑" (father's sister), and "姨妈" (mother's sister) are indicative of the hierarchical and family - based social structure of traditional Chinese society. The terms indicate not only various family relationships but also particular social roles and expectations. Consequently, e.g., in Spanish cultures, the use or non-use of "tú" (familiar) and "usted" (formal) pronouns is a major marker of social rules of interaction, explaining the significance of social status and formality within their societies (Romero, 2015). As the individual learns the language, he/she becomes aware of the unstated social codes and institutions that govern the interactions of the group.

3. Facilitating cultural exchange: Language as the Bridge of Authentic Interaction

Language capacity is the key to productive cultural exchange. Skutnabb - Kangas (2000) pointed out that translating at times does not capture the entire cultural context, and thus there is a "cultural discount." The French expression "joie de vivre," for instance, cannot be translated to a corresponding phrase in English. While it may be translated as "joy of living," this does not capture the rich cultural overtones that come with the French philosophy of reveling in life with gusto. With the acquisition of a language, one becomes privy to the cultural subtleties, idiomatic locutions, and home humor that are vital for real cultural exchange. This allows for greater depth of more spontaneous interaction and better understanding of the worldview of the cultural community.

4. Declaring ethnologic interests: Language as the Flag of Ethnicity

Language is a significant ethnic symbol and can serve as a vehicle for declaring ethnologic interests. Fishman (1991) underscored the close relationship between the practice of language and ethnic cohesion. Revival of the Irish Gaelic language in Ireland is a typical example. By means of education initiatives, cultural festivals, and Gaelic media, the Irish have been able to propagate their ethnic identity and preserve their unique cultural heritage (O'Riagain, 2005). Similarly, most indigenous languages in the world, such as the Navajo language in North America, preserve the intelligence, traditions, and spiritual principles of the native people. With such languages mastered, there is respect and understanding of ethnologic interests and identities of the said communities.

5. Shaping cultural evolution: Language as the Driving Force of Cultural Change

Language is a living force, and it drives cultural evolution. New words, phrases, and forms of language emerge as reactions to social, technological, and cultural developments, and in return, they determine the course of cultural evolution. In English-speaking cultures, the rapid evolution of internet-related vocabulary such as "emoji," "selfie," and "vlog" has not only changed the way people communicate but also given birth to new forms of digital culture (Baron, 2008). In Japan, extensive borrowing from foreign languages and the creation of indigenous portmanteaus have been key drivers of the country's cultural evolution and growth (Ito et al., 2013). By acquiring the language of a social group, one can observe and make sense of the ongoing cultural development and the mechanisms underlying it.

6. Forming cultural symbols: Language as the Interpreter of Symbolic Meanings

Language gives meaning to cultural symbols. Saussure's (1916) semiotic theory assumes that the link between a signifier (the form of a sign) and a signified (the concept it signifies) is established through language. For example, the Chinese character \"福\" (fu), meaning "good fortune," is a powerful cultural symbol in Chinese New Year. Its symbolism and meaning stem deeply from the Chinese culture and the language. In contrast, the word "snake" has different symbolic meanings in Western and Eastern cultures. It has been associated in Western societies with evil and temptation, while in some Eastern societies it can be symbolic of wisdom and transformation. By knowing the language, the complex symbolic meanings that constitute a basic element of the identity of a cultural group are correctly understood (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980).

7. The creation of historical memory: Language as keeper of heritage

Language serves to act as the keeper of the historic memory of a cultural group. Halbwachs (1925) posited that collective memory is communicated and retained through language. Oral tradition, ancient texts, and written documents are all documented in language, including the stories, experiences, and information of past generations. For example, the ancient Greek epics, such as the "Iliad" and the "Odyssey," composed in the Greek language, have provided invaluable insights into ancient Greek culture, values, and history. In Africa, the oral culture of griots, which employs language to transmit genealogies, histories, and cultural values, maintains cultural memory (Jahn, 1961). Through the acquisition of the language of a cultural group, one has access to and an understanding of these histories, linking him/her to the past of the group and gaining an appreciation for the heritage of its culture.

In short, learning the language of a group of people is more than an intellectual exercise or utilitarian communicative skill; it is a prerequisite for comprehensive and penetrating investigation of a culture. From value formation and social institutions to remembering history and offering cultural exchange, language offers a unique and precious perspective of the essence of a cultural group. It is only through the process of acquiring the language that we can actually dismantle the cultural barriers, build the bridges of understanding, and appreciate the diversity richness of human cultures.

Unveiling English Culture through Royal - related Vocabulary: A Linguistic Journey

English Language Example in England: Royal - related Vocabulary

English abounds with a rich tapestry of monarchical terms of considerable depth of cultural, historical, and social significance. Terms such as "crown," "throne," "coronation," "regency," "heir apparent," "duchy," "earl," and "peerage" are not just tools of the language but windows into the soul of English culture.

The term "crown," for instance, is far greater than a denotative expression for a tangible apparatus on which the king sits. The crown throughout history has been an emblem that symbolizes sovereignty as well as power. The crown in medieval England was oftentimes conceived of as a divine-right emblem, meaning that the king's power came from God (Cam, H. M. (1963). England before Elizabeth. Harvard University Press.). This is a notion deeply rooted in English historical consciousness. The celebrated "Crown Jewels," which include the Imperial State Crown, the Sceptre with Cross, and the Orb, are not only priceless items but also symbols of national identity. Their preservation and display at the Tower of London confirm the monarchy and national heritage's continuity.

The word "throne" represents the throne of monarchical power. It is used metaphorically in such expressions as "ascend the throne" or "sit on the throne," expressing a monarch's assumption of power and ruling. They have been used in centuries-long histories, writings, and government documents to emphasize the monarchical foundation of hierarchical English society. Histories of the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 and subsequent English royal successions usually refer to the new rulers "ascending the throne," stressing the significance of the act within political and social institutions of the nation (Doubleday, G. (1972). William the Conqueror. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.).

"Coronation," the ceremony by which a sovereign is officially crowned, is another historically tradition-soaked word. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 was an international event watched by millions. The formal ceremonies, the use of some regalia, and the anointing with consecrated oil are all derived from centuries- old customs. Its name itself, from Latin, has been used in English for these gravitas ceremonies since the Middle Ages, and it holds within it the history and gravitas of the monarchy and significance in English cultural life (Long, J. (2018). Coronation: A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy. The History Press.).

The word "peerage," or the titled nobility which supports the monarchy, appears in such words as "duke," "earl," and "baron." These words signify not just social rank but also have their origins in early historical sources of land ownership, military service, and political authority in medieval England. The peerage system, its complex hierarchy having pervaded English existence for over a millennium, the lexicon lends itself to the retention of the understanding of this social hierarchy (Carpenter, D. (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066 - 1284. Penguin Books.).

Analysis based on the seven outstanding points

1. Values formation

The prevalence of royal - focused vocabulary in the English language instills values of tradition, deference to authority, and loyalty. The continued use of terms like "crown" and "throne" in common usage, literature, and governmental rhetoric entrenches the belief in a long - standing, unbroken line of ruling. These terms instill a sense of security and continuity, highly cherished in English society. For example, when ordinary citizens refer to the monarchy, their use indicates automatically a respect for the institution and the traditions it represents.

2. Creating social systems

Monarchical terminology mirrors the hierarchical nature of England's social system. Words used to describe differing ranks in the peerage, such as "duke" and "baron," unambiguously identify social rank and role. Earlier, the royal family occupied the apex of this social hierarchy, and the resulting vocabulary retained the social stratification. Even in today's more egalitarian England, the remnants of this hierarchical vocabulary still influence social attitudes and conduct, such as deference given to titles in some formal situations.

3. Facilitating cultural exchange

Royal - associated English words are a good facilitator of cultural exchange. When they hear terms like "coronation" or "royal wedding" in foreign audiences, they are drawn to the unique traditions of England by nature. Foreign coverage of weddings involving Prince William and Kate Middleton, and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, used these English words freely, projecting English royal culture for international viewers across the globe. This vocabulary is a cultural envoy, communicating the rich richness of English traditions and ceremonies.

4. Declaring ethnologic interests

Use of this technical vocabulary is a matter-of-fact articulation of English ethnic interests. It is used to highlight the Englishness of English history and culture, setting it apart from other nations. The monarchy has been an integral aspect of English identity over the centuries, and the associated language is a pointer to this unique inheritance. English folks identify such words as the origin of cultural identity and ways of announcing their bond to their national heritage.

5. Shaping cultural evolution

The definition and associations of royal - related words have shifted historically, reflecting English cultural progress. As the traditional authority of the monarchy diminished, words "crown" and "throne" more symbolically and culturally signify today. For example, the role of the monarchy today is more about soft power and national identity, and the language used to describe it has been similarly adapted. The increased popular fascination with the private lives of members of the royal family, as evidenced by the media's use of terms like "royal romance" or "royal scandal," also reflects how the monarchy modifies language and image to suit the times.

6. Shaping cultural symbols

Monarchical terms are some of the most powerful English cultural symbols. "Crown" is instantly known as a national symbol, and the word itself evokes thoughts of majesty, tradition, and authority. Similarly, "throne" also evokes power and domination. They appear in everything from national symbols and governmental emblems to pieces of literature and art, cementing their place in English cultural consciousness.

7. Creating historical memory

Royal-related terms are an essential element in creating English historical memory. "Coronation" and "regency" are used to describe significant historical periods and events. They help English people remember the sequence of kings and queens, key events in royal history, and the nation-building process. School textbooks, documentaries about history, and cultural heritage sites all use this vocabulary to educate and keep alive the nation's past so that the next generation would know about the place of the monarchy in the history of England.

References

Baron, N. S. (2008). Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World. Oxford University Press.

Basso, K. H. (1996). Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. University of New Mexico Press.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, D. (2000). Language and Power. Polity Press.

Fishman, J. A. (1991). Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Multilingual Matters.

Foucault, M. (1972). The Archaeology of Knowledge. Pantheon Books.

Halbwachs, M. (1925). Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. Alcan.

Ito, M., et al. (2013). Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. MIT Press.

Jahn, J. (1961). Muntu: An Outline of the New African Culture. Faber & Faber.

Kame'eleihiwa, L. S. (1992). Native Land and Foreign Desires. Bishop Museum Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press.

O'Riagain, P. (2005). Language Revitalization in Ireland. Multilingual Matters.

Romero, M. (2015). Spanish Pronouns and Sociolinguistic Variation. Routledge.

Saussure, F. de. (1916). Cours de linguistique générale. Payot.

Skutnabb - Kangas, T. (2000). Linguistic Genocide in Education - or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights? Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Whorf, B. L. (1956). Language, Thought, and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. MIT Press.

Williams, G. (1985). When Was Wales? A Historical Outline. University of Wales Press.

Cam, H. M. (1963). England before Elizabeth. Harvard University Press.

Carpenter, D. (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: The Penguin History of Britain 1066 - 1284. Penguin Books.

Doubleday, G. (1972). William the Conqueror. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Long, J. (2018). Coronation: A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy. The History Press

语言与文化:深入理解文化的关键

语言与文化:深入理解文化的关键

285

285

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?