注:本文为 “数学教育” 相关合辑。

英文引文,机翻未校。

如有内容异常,请看原文。

A Mathematician’s Lament

一位数学家的叹息

by Paul Lockhart

保罗·洛克哈特 著

A musician wakes from a terrible nightmare. In his dream he finds himself in a society where music education has been made mandatory. “We are helping our students become more competitive in an increasingly sound-filled world.” Educators, school systems, and the state are put in charge of this vital project. Studies are commissioned, committees are formed, and decisions are made- all without the advice or participation of a single working musician or composer.

一位音乐家从一场可怕的噩梦中惊醒。梦中,他置身于一个将音乐教育列为必修课的社会。“在这个日益充斥着声音的世界里,我们正在帮助学生提升竞争力。”教育工作者、学校系统和政府负责主导这一重要项目。相关研究纷纷启动,各类委员会相继成立,各项决策陆续出台——而这一切,却没有征求任何一位在职音乐家或作曲家的意见,也没有让他们参与其中。

Since musicians are known to set down their ideas in the form of sheet music, these curious black dots and lines must constitute the “language of music.” It is imperative that students become fluent in this language if they are to attain any degree of musical competence; indeed, it would be ludicrous to expect a child to sing a song or play an instrument without having a thorough grounding in music notation and theory. Playing and listening to music, let alone composing an original piece, are considered very advanced topics and are generally put off until college, and more often graduate school.

众所周知,音乐家会以乐谱的形式记录自己的想法,因此这些奇特的黑点和线条必然就是“音乐的语言”。学生若想在音乐方面达到一定的造诣,熟练掌握这门语言至关重要;事实上,若没有扎实的音乐记谱法和理论基础,就期望孩子能唱歌或演奏乐器,那简直是天方夜谭。演奏和聆听音乐,更不用说创作原创作品,都被视为非常高深的内容,通常要推迟到大学,甚至研究生阶段才会涉及。

As for the primary and secondary schools, their mission is to train students to use this language- to jiggle symbols around according to a fixed set of rules: “Music class is where we take out our staff paper, our teacher puts some notes on the board, and we copy them or transpose them into a different key. We have to make sure to get the clefs and key signatures right, and our teacher is very picky about making sure we fill in our quarter-notes completely. One time we had a chromatic scale problem and I did it right, but the teacher gave me no credit because I had the stems pointing the wrong way.”

而中小学的使命,则是训练学生使用这门语言——按照一套固定的规则摆弄这些符号:“音乐课上,我们拿出五线谱纸,老师在黑板上写下一些音符,我们要么抄写下来,要么转调到另一个调式。我们必须确保谱号和调号不出错,老师对四分音符的填写是否完整也格外挑剔。有一次我做半音阶的题目完全做对了,但老师却没给我分,就因为音符的符干方向错了。”

In their wisdom, educators soon realize that even very young children can be given this kind of musical instruction. In fact it is considered quite shameful if one’s third-grader hasn’t completely memorized his circle of fifths. “I’ll have to get my son a music tutor. He simply won’t apply himself to his music homework. He says it’s boring. He just sits there staring out the window, humming tunes to himself and making up silly songs.”

教育工作者们“英明地”很快意识到,即便非常年幼的孩子也能接受这种音乐教学。事实上,如果一个三年级学生还没有完全记住五度圈,会被认为是相当丢脸的事。“我得给儿子请个音乐家教了。他根本不认真做音乐作业,说太无聊了。他就坐在那儿盯着窗外,自己哼着调子,编些傻兮兮的歌。”

In the higher grades the pressure is really on. After all, the students must be prepared for the standardized tests and college admissions exams. Students must take courses in Scales and Modes, Meter, Harmony, and Counterpoint. “It’s a lot for them to learn, but later in college when they finally get to hear all this stuff, they’ll really appreciate all the work they did in high school.” Of course, not many students actually go on to concentrate in music, so only a few will ever get to hear the sounds that the black dots represent. Nevertheless, it is important that every member of society be able to recognize a modulation or a fugal passage, regardless of the fact that they will never hear one. “To tell you the truth, most students just aren’t very good at music. They are bored in class, their skills are terrible, and their homework is barely legible. Most of them couldn’t care less about how important music is in today’s world; they just want to take the minimum number of music courses and be done with it. I guess there are just music people and non-music people. I had this one kid, though, man was she sensational! Her sheets were impeccable- every note in the right place, perfect calligraphy, sharps, flats, just beautiful. She’s going to make one hell of a musician someday.”

到了高年级,压力就真的来了。毕竟,学生们必须为标准化考试和大学入学考试做准备。他们要学习音阶与调式、节拍、和声与对位法等课程。“要学的东西太多了,但等他们上了大学,终于能听到这些内容的实际音效时,就会真心感激高中时付出的努力。”当然,实际上并没有多少学生会继续主修音乐,所以只有少数人能真正听到这些黑点所代表的声音。尽管如此,社会中的每一个成员都应该能够识别转调或赋格段落,即便他们这辈子都不会听到这些东西,这一点依然很重要。“说实话,大多数学生其实并不擅长音乐。他们在课堂上感到无聊,技能糟糕透顶,作业写得难以辨认。他们大多根本不在乎音乐在当今世界有多重要,只是想修完最少的音乐课程,赶紧了事。我想,人大概分为有音乐天赋的和没有音乐天赋的吧。不过我曾遇到过一个孩子,天哪,她简直太棒了!她的乐谱无可挑剔——每个音符都在正确的位置,书写完美,升号、降号都恰到好处,真是太美了。她将来一定会成为一名了不起的音乐家。”

Waking up in a cold sweat, the musician realizes, gratefully, that it was all just a crazy dream. “Of course!” he reassures himself, “No society would ever reduce such a beautiful and meaningful art form to something so mindless and trivial; no culture could be so cruel to its children as to deprive them of such a natural, satisfying means of human expression. How absurd!”

音乐家浑身冷汗地醒来,心怀感激地意识到,这一切都只是一场疯狂的噩梦。“当然!”他安慰自己,“没有哪个社会会把如此美丽而有意义的艺术形式简化成如此空洞乏味、微不足道的东西;没有哪种文化会对自己的孩子如此残忍,剥夺他们这种自然而令人愉悦的人类表达方式。这太荒谬了!”

Meanwhile, on the other side of town, a painter has just awakened from a similar nightmare…

与此同时,在城镇的另一头,一位画家也从一场类似的噩梦中惊醒……

I was surprised to find myself in a regular school classroom- no easels, no tubes of paint. “Oh we don’t actually apply paint until high school,” I was told by the students. “In seventh grade we mostly study colors and applicators.” They showed me a worksheet. On one side were swatches of color with blank spaces next to them. They were told to write in the names. “I like painting,” one of them remarked, “they tell me what to do and I do it. It’s easy!”

我惊讶地发现自己身处一间普通的学校教室——没有画架,没有颜料管。“哦,我们要到高中才真正开始画画呢,”学生们告诉我,“七年级主要是学习颜色和绘画工具。”他们给我看了一张作业纸,一边是各种颜色的色卡,旁边留着空白,要求他们写下颜色的名称。“我喜欢画画,”其中一个学生说,“他们告诉我要做什么,我照做就行,很简单!”

After class I spoke with the teacher. “So your students don’t actually do any painting?” I asked. “Well, next year they take Pre-Paint-by-Numbers. That prepares them for the main Paint-by-Numbers sequence in high school. So they’ll get to use what they’ve learned here and apply it to real-life painting situations- dipping the brush into paint, wiping it off, stuff like that. Of course we track our students by ability. The really excellent painters- the ones who know their colors and brushes backwards and forwards- they get to the actual painting a little sooner, and some of them even take the Advanced Placement classes for college credit. But mostly we’re just trying to give these kids a good foundation in what painting is all about, so when they get out there in the real world and paint their kitchen they don’t make a total mess of it.”

课后我和老师聊了起来。“这么说,你的学生们其实根本不画画?”我问。“嗯,明年他们会学‘数字填色预备课’,为高中的核心数字填色课程做准备。这样他们就能把在这里学到的知识应用到实际的绘画场景中——比如把刷子蘸上颜料,再擦掉多余的,之类的。当然,我们会根据学生的能力进行分层教学。那些真正优秀的画家——也就是对颜色和画笔了如指掌的学生——会更早开始真正的绘画,有些人甚至会参加大学先修课程,以获得大学学分。但总的来说,我们只是想让这些孩子打好绘画基础,这样他们将来在现实生活中给自己的厨房刷漆时,不会弄得一团糟。”

“Um, these high school classes you mentioned…”

“嗯,你说的那些高中课程……”

“You mean Paint-by-Numbers? We’re seeing much higher enrollments lately. I think it’s mostly coming from parents wanting to make sure their kid gets into a good college. Nothing looks better than Advanced Paint-by-Numbers on a high school transcript.”

“你是说数字填色课?最近报名的人多了很多。我觉得主要是因为家长们想确保孩子能进入好大学。高中成绩单上有‘高级数字填色’这门课,看起来可是相当不错的。”

“Why do colleges care if you can fill in numbered regions with the corresponding color?”

“为什么大学会在意你是否能给编号的区域填上对应的颜色呢?”

“Oh, well, you know, it shows clear-headed logical thinking. And of course if a student is planning to major in one of the visual sciences, like fashion or interior decorating, then it’s really a good idea to get your painting requirements out of the way in high school.”

“哦,你知道的,这能体现清晰的逻辑思维能力。当然,如果学生打算主修视觉相关专业,比如时尚设计或室内装饰,那么在高中就完成绘画相关的必修要求,确实是个好主意。”

“I see. And when do students get to paint freely, on a blank canvas?”

“我明白了。那学生们什么时候才能在空白的画布上自由创作呢?”

“You sound like one of my professors! They were always going on about expressing yourself and your feelings and things like that-really way-out-there abstract stuff. I’ve got a degree in Painting myself, but I’ve never really worked much with blank canvasses. I just use the Paint-by-Numbers kits supplied by the school board.”

“你这话听起来像我的大学教授们!他们总是滔滔不绝地谈论自我表达、情感抒发之类的——都是些非常抽象、不着边际的东西。我自己有绘画学位,但从来没怎么在空白画布上创作过。我只用学校董事会提供的数字填色套装。”

Sadly, our present system of mathematics education is precisely this kind of nightmare. In fact, if I had to design a mechanism for the express purpose of destroying a child’s natural curiosity and love of pattern-making, I couldn’t possibly do as good a job as is currently being done- I simply wouldn’t have the imagination to come up with the kind of senseless, soul-crushing ideas that constitute contemporary mathematics education.

可悲的是,我们现行的数学教育体系正是这样一场噩梦。事实上,如果我必须设计一个专门用来摧毁孩子天生的好奇心和对模式探索热爱的机制,我绝对做不到现在这么好——我根本没有想象力能想出那些构成当代数学教育的、毫无意义且摧残心灵的主意。

Everyone knows that something is wrong. The politicians say, “we need higher standards.” The schools say, “we need more money and equipment.” Educators say one thing, and teachers say another. They are all wrong. The only people who understand what is going on are the ones most often blamed and least often heard: the students. They say, “math class is stupid and boring,” and they are right.

每个人都知道哪里出了问题。政客们说:“我们需要更高的标准。”学校说:“我们需要更多的资金和设备。”教育专家们各执一词,老师们也有自己的说法。但他们都错了。唯一明白真相的,是那些最常被指责、却最没人愿意倾听的人:学生们。他们说:“数学课又蠢又无聊”,而他们是对的。

Mathematics and Culture

数学与文化

The first thing to understand is that mathematics is an art. The difference between math and the other arts, such as music and painting, is that our culture does not recognize it as such. Everyone understands that poets, painters, and musicians create works of art, and are expressing themselves in word, image, and sound. In fact, our society is rather generous when it comes to creative expression; architects, chefs, and even television directors are considered to be working artists. So why not mathematicians?

首先要明白的是,数学是一门艺术。数学与音乐、绘画等其他艺术形式的区别在于,我们的文化并不认可它的艺术属性。每个人都知道诗人、画家和音乐家创作艺术作品,通过文字、图像和声音表达自我。事实上,我们的社会对创造性表达相当宽容:建筑师、厨师,甚至电视导演都被视为在职的艺术家。那么,为什么数学家不能呢?

Part of the problem is that nobody has the faintest idea what it is that mathematicians do. The common perception seems to be that mathematicians are somehow connected with science- perhaps they help the scientists with their formulas, or feed big numbers into computers for some reason or other. There is no question that if the world had to be divided into the “poetic dreamers” and the “rational thinkers” most people would place mathematicians in the latter category.

部分问题在于,没有人真正知道数学家到底在做什么。普遍的看法似乎是,数学家多少与科学有关——也许他们帮科学家推导公式,或者出于某种原因把大数字输入电脑。毫无疑问,如果要把世界上的人分为“诗意的梦想家”和“理性的思考者”,大多数人会把数学家归到后一类。

Nevertheless, the fact is that there is nothing as dreamy and poetic, nothing as radical, subversive, and psychedelic, as mathematics. It is every bit as mind blowing as cosmology or physics (mathematicians conceived of black holes long before astronomers actually found any), and allows more freedom of expression than poetry, art, or music (which depend heavily on properties of the physical universe). Mathematics is the purest of the arts, as well as the most misunderstood.

然而,事实是,没有什么比数学更富有梦想与诗意,更激进、颠覆且令人迷醉。它和宇宙学或物理学一样令人震撼(数学家在天文学家真正发现黑洞之前很久就构想过黑洞的存在),而且比诗歌、艺术或音乐提供了更多的表达自由(这些艺术形式严重依赖物理宇宙的属性)。数学是最纯粹的艺术,也是最被误解的艺术。

So let me try to explain what mathematics is, and what mathematicians do. I can hardly do better than to begin with G.H. Hardy’s excellent description:

因此,让我试着解释一下数学是什么,数学家们在做什么。我最好从 G.H. 哈代的精彩描述开始:

A mathematician, like a painter or poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent than theirs, it is because they are made with ideas.

数学家,就像画家或诗人一样,是模式的创造者。如果说他的模式比他们的更持久,那是因为这些模式是用思想构建的。

So mathematicians sit around making patterns of ideas. What sort of patterns? What sort of ideas? Ideas about the rhinoceros? No, those we leave to the biologists. Ideas about language and culture? No, not usually. These things are all far too complicated for most mathematicians’ taste. If there is anything like a unifying aesthetic principle in mathematics, it is this: simple is beautiful. Mathematicians enjoy thinking about the simplest possible things, and the simplest possible things are imaginary.

所以,数学家们四处思索,构建思想的模式。什么样的模式?什么样的思想?关于犀牛的思想?不,那是生物学家的事。关于语言和文化的思想?通常也不是。这些东西对大多数数学家来说都太复杂了。如果说数学中存在某种统一的美学原则,那就是:简单即美。数学家们喜欢思考最简单的事物,而最简单的事物往往是想象出来的。

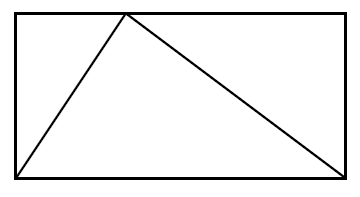

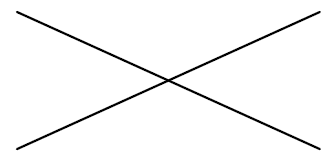

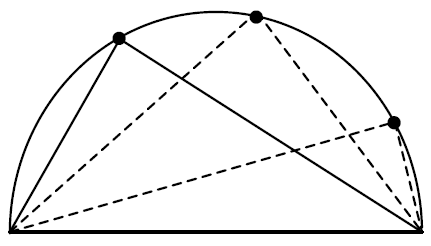

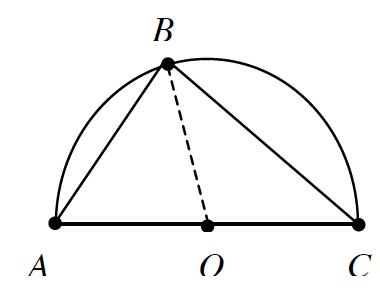

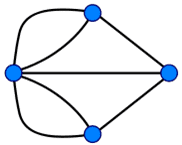

For example, if I’m in the mood to think about shapes- and I often am- I might imagine a triangle inside a rectangular box:

例如,如果我有心情思考形状——我经常这样——我可能会想象一个矩形盒子里有一个三角形:

I wonder how much of the box the triangle takes up? Two-thirds maybe? The important thing to understand is that I’m not talking about this drawing of a triangle in a box. Nor am I talking about some metal triangle forming part of a girder system for a bridge. There’s no ulterior practical purpose here. I’m just playing. That’s what math is- wondering, playing, amusing yourself with your imagination. For one thing, the question of how much of the box the triangle takes up doesn’t even make any sense for real, physical objects. Even the most carefully made physical triangle is still a hopelessly complicated collection of jiggling atoms; it changes its size from one minute to the next. That is, unless you want to talk about some sort of approximate measurements. Well, that’s where the aesthetic comes in. That’s just not simple, and consequently it is an ugly question which depends on all sorts of real-world details. Let’s leave that to the scientists. The mathematical question is about an imaginary triangle inside an imaginary box. The edges are perfect because I want them to be- that is the sort of object I prefer to think about. This is a major theme in mathematics: things are what you want them to be. You have endless choices; there is no reality to get in your way.

我想知道这个三角形占据了盒子多大的空间?也许是三分之二?关键要明白的是,我谈论的不是这张画在盒子里的三角形,也不是桥梁梁架系统中某个金属三角形部件。这里没有任何潜在的实际用途,我只是在玩耍。这就是数学——好奇、玩耍、用想象力自娱自乐。首先,对于真实的物理物体来说,“三角形占据盒子多大空间”这个问题本身就没有意义。即使是制作最精良的物理三角形,也只是由不断晃动的原子组成的复杂集合,其大小每时每刻都在变化——除非你想讨论某种近似测量。而这就涉及到美学了:这种问题并不简单,因此是个丑陋的问题,它依赖于各种现实世界的细节。让科学家们去处理这些吧。数学问题关注的是想象中的盒子里那个想象中的三角形。它的边是完美的,因为我希望它们是完美的——这正是我喜欢思考的那种对象。这是数学的一个重要主题:事物可以是你希望的样子。你有无限的选择,没有现实的束缚。

On the other hand, once you have made your choices (for example I might choose to make my triangle symmetrical, or not) then your new creations do what they do, whether you like it or not. This is the amazing thing about making imaginary patterns: they talk back! The triangle takes up a certain amount of its box, and I don’t have any control over what that amount is. There is a number out there, maybe it’s two-thirds, maybe it isn’t, but I don’t get to say what it is. I have to find out what it is.

但另一方面,一旦你做出了选择(比如我可能选择让三角形对称,也可能不选),你新创造的事物就会按其自身规律发展,无论你是否喜欢。这就是构建想象模式的奇妙之处:它们会“回应”你!这个三角形占据了盒子的一定空间,而我无法控制这个空间的大小。存在一个确定的数值,可能是三分之二,也可能不是,但我说了不算,我必须去发现它到底是多少。

So we get to play and imagine whatever we want and make patterns and ask questions about them. But how do we answer these questions? It’s not at all like science. There’s no experiment I can do with test tubes and equipment and whatnot that will tell me the truth about a figment of my imagination. The only way to get at the truth about our imaginations is to use our imaginations, and that is hard work.

因此,我们可以尽情玩耍、畅想,构建各种模式,然后对它们提出问题。但我们如何回答这些问题呢?这和科学完全不同。我无法用试管、设备之类的东西做实验,来验证我想象中的事物的真相。了解我们想象之物真相的唯一方法,就是运用我们的想象力,而这是一项艰巨的工作。

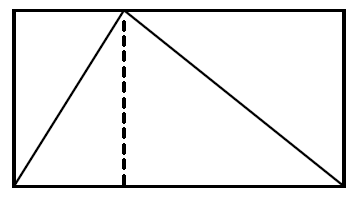

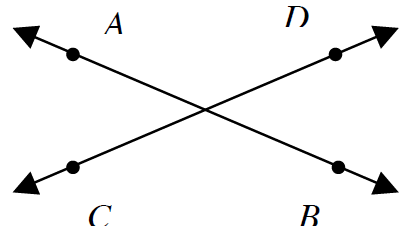

In the case of the triangle in its box, I do see something simple and pretty:

以盒子里的三角形为例,我确实发现了一些简单而优美的规律:

If I chop the rectangle into two pieces like this, I can see that each piece is cut diagonally in half by the sides of the triangle. So there is just as much space inside the triangle as outside. That means that the triangle must take up exactly half the box!

如果我把矩形这样切成两半,就能发现三角形的边把每一半都对角平分了。因此,三角形内部的空间和外部的空间一样大,这意味着三角形恰好占据了盒子的一半空间!

This is what a piece of mathematics looks and feels like. That little narrative is an example of the mathematician’s art: asking simple and elegant questions about our imaginary creations, and crafting satisfying and beautiful explanations. There is really nothing else quite like this realm of pure idea; it’s fascinating, it’s fun, and it’s free!

这就是数学的样子和感觉。这段简短的推理就是数学家艺术的一个例子:对我们想象中的创造物提出简单而优雅的问题,并给出令人满意且优美的解释。这个纯粹的思想领域是独一无二的;它迷人、有趣,而且无拘无束!

Now where did this idea of mine come from? How did I know to draw that line? How does a painter know where to put his brush? Inspiration, experience, trial and error, dumb luck. That’s the art of it, creating these beautiful little poems of thought, these sonnets of pure reason. There is something so wonderfully transformational about this art form. The relationship between the triangle and the rectangle was a mystery, and then that one little line made it obvious. I couldn’t see, and then all of a sudden I could. Somehow, I was able to create a profound simple beauty out of nothing, and change myself in the process. Isn’t that what art is all about?

那么,我的这个想法是从哪里来的?我怎么知道要画那条线?就像画家怎么知道画笔该落在何处一样?答案是灵感、经验、反复尝试,还有一点运气。这就是艺术的本质——创造这些美丽的思想小诗,这些纯粹理性的十四行诗。这种艺术形式具有一种奇妙的变革力量。三角形和矩形之间的关系曾经是个谜,而那条小小的线让一切豁然开朗。我之前一直困惑不解,然后突然间恍然大悟。不知何故,我从无到有地创造出了一种深邃而简单的美,并且在这个过程中改变了自己。这不正是艺术的意义所在吗?

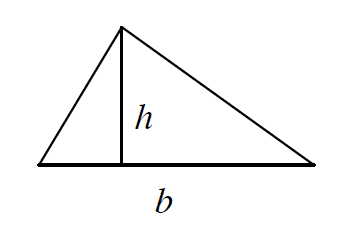

This is why it is so heartbreaking to see what is being done to mathematics in school. This rich and fascinating adventure of the imagination has been reduced to a sterile set of “facts” to be memorized and procedures to be followed. In place of a simple and natural question about shapes, and a creative and rewarding process of invention and discovery, students are treated to this: Triangle Area Formula:

这就是为什么看到学校里对数学所做的一切会如此令人心碎。这场丰富而迷人的想象力冒险,被简化成了一套僵化的“事实”让学生记忆,以及一系列需要遵循的步骤。学生们没有得到关于形状的简单而自然的问题,也没有体验到富有创造性和成就感的发明与发现过程,取而代之的是这个:三角形面积公式:

A

=

1

/

2

b

h

A=1 / 2 \ b \ h

A=1/2 b h

“The area of a triangle is equal to one-half its base times its height.” Students are asked to memorize this formula and then “apply” it over and over in the “exercises.” Gone is the thrill, the joy, even the pain and frustration of the creative act. There is not even a problem anymore. The question has been asked and answered at the same time- there is nothing left for the student to do.

“三角形的面积等于底乘以高的一半。”学生们被要求记住这个公式,然后在“练习题”中反复“应用”。创造性行为带来的兴奋、喜悦,甚至痛苦和挫折感,都消失了。这里甚至不再有“问题”可言——问题和答案同时被给出,学生没有任何可以自主完成的事情。

Now let me be clear about what I’m objecting to. It’s not about formulas, or memorizing interesting facts. That’s fine in context, and has its place just as learning a vocabulary does- it helps you to create richer, more nuanced works of art. But it’s not the fact that triangles take up half their box that matters. What matters is the beautiful idea of chopping it with the line, and how that might inspire other beautiful ideas and lead to creative breakthroughs in other problems- something a mere statement of fact can never give you.

现在我要明确说明我反对的是什么。我反对的不是公式本身,也不是记忆有趣的事实。在合适的语境下,这些都是有益的,就像学习词汇一样——它们能帮助你创造更丰富、更细腻的艺术作品。但重要的不是“三角形占据盒子一半空间”这个事实,而是用线条分割的那个优美想法,以及这个想法如何启发其他优美的思路,并在其他问题中带来创造性的突破——这是单纯陈述事实永远无法给予的。

By removing the creative process and leaving only the results of that process, you virtually guarantee that no one will have any real engagement with the subject. It is like saying that Michelangelo created a beautiful sculpture, without letting me see it. How am I supposed to be inspired by that? (And of course it’s actually much worse than this- at least it’s understood that there is an art of sculpture that I am being prevented from appreciating).

移除创造性过程,只留下过程的结果,你实际上就保证了没有人会真正投入到这门学科中。这就像有人告诉你米开朗基罗创作了一座美丽的雕塑,却不让你亲眼看到它。我怎么可能从中获得灵感呢?(当然,实际情况更糟——至少人们知道雕塑是一门艺术,而我只是被剥夺了欣赏它的机会。)

By concentrating on what, and leaving out why, mathematics is reduced to an empty shell. The art is not in the “truth” but in the explanation, the argument. It is the argument itself which gives the truth its context, and determines what is really being said and meant. Mathematics is the art of explanation. If you deny students the opportunity to engage in this activity- to pose their own problems, make their own conjectures and discoveries, to be wrong, to be creatively frustrated, to have an inspiration, and to cobble together their own explanations and proofs- you deny them mathematics itself. So no, I’m not complaining about the presence of facts and formulas in our mathematics classes, I’m complaining about the lack of mathematics in our mathematics classes.

只关注“是什么”,而忽略“为什么”,数学就变成了一个空洞的外壳。艺术不在于“真相”本身,而在于解释和论证。正是论证赋予了真相语境,决定了它真正的含义。数学是解释的艺术。如果你剥夺了学生参与这种活动的机会——让他们提出自己的问题、做出自己的猜想和发现、犯错、经历创造性的挫折、获得灵感,并拼凑出自己的解释和证明——你就剥夺了他们真正接触数学的机会。因此,我抱怨的不是数学课堂上有事实和公式,而是抱怨我们的数学课堂上缺乏真正的数学。

If your art teacher were to tell you that painting is all about filling in numbered regions, you would know that something was wrong. The culture informs you- there are museums and galleries, as well as the art in your own home. Painting is well understood by society as a medium of human expression. Likewise, if your science teacher tried to convince you that astronomy is about predicting a person’s future based on their date of birth, you would know she was crazy- science has seeped into the culture to such an extent that almost everyone knows about atoms and galaxies and laws of nature. But if your math teacher gives you the impression, either expressly or by default, that mathematics is about formulas and definitions and memorizing algorithms, who will set you straight?

如果你的美术老师告诉你,绘画就是给编号的区域填色,你会立刻知道哪里不对劲。文化会告诉你答案——有博物馆、画廊,还有你家里的艺术品。社会普遍认为绘画是人类表达的一种媒介。同样,如果你的科学老师试图让你相信,天文学是根据一个人的出生日期预测未来,你会知道她疯了——科学已经深深融入文化,几乎每个人都知道原子、星系和自然规律。但如果你的数学老师明确地,或者默认地让你觉得,数学就是公式、定义和记忆算法,谁会来纠正你呢?

The cultural problem is a self-perpetuating monster: students learn about math from their teachers, and teachers learn about it from their teachers, so this lack of understanding and appreciation for mathematics in our culture replicates itself indefinitely. Worse, the perpetuation of this “pseudo-mathematics,” this emphasis on the accurate yet mindless manipulation of symbols, creates its own culture and its own set of values. Those who have become adept at it derive a great deal of self-esteem from their success. The last thing they want to hear is that math is really about raw creativity and aesthetic sensitivity. Many a graduate student has come to grief when they discover, after a decade of being told they were “good at math,” that in fact they have no real mathematical talent and are just very good at following directions. Math is not about following directions, it’s about making new directions.

这个文化问题是一个自我延续的怪物:学生从老师那里学习数学,老师又从他们的老师那里学习数学,因此这种对数学的不理解和不欣赏在我们的文化中无限复制。更糟糕的是,这种“伪数学”的持续存在——强调准确但机械地操纵符号——形成了自己的文化和价值观。那些擅长这种伪数学的人从自己的成功中获得了极大的自尊,他们最不愿意听到的就是“数学本质上是原始的创造力和审美敏感度”。许多研究生在被认为“擅长数学”十年后,突然发现自己其实没有真正的数学天赋,只是非常善于遵循指令,这让他们陷入了痛苦。数学不是遵循指令,而是开辟新的方向。

And I haven’t even mentioned the lack of mathematical criticism in school. At no time are students let in on the secret that mathematics, like any literature, is created by human beings for their own amusement; that works of mathematics are subject to critical appraisal; that one can have and develop mathematical taste. A piece of mathematics is like a poem, and we can ask if it satisfies our aesthetic criteria: Is this argument sound? Does it make sense? Is it simple and elegant? Does it get me closer to the heart of the matter? Of course there’s no criticism going on in school- there’s no art being done to criticize!

我甚至还没提到学校里缺乏数学批评。学生们从来没有被告知这个秘密:数学和任何文学作品一样,是人类为了自娱自乐而创造的;数学作品也需要批判性评价;人们可以拥有并培养数学品味。一篇数学作品就像一首诗,我们可以问:这个论证是否合理?是否有意义?是否简单优雅?是否触及了问题的核心?当然,学校里根本没有这种批评——因为根本没有真正的数学艺术可供批评!

Why don’t we want our children to learn to do mathematics? Is it that we don’t trust them, that we think it’s too hard? We seem to feel that they are capable of making arguments and coming to their own conclusions about Napoleon, why not about triangles? I think it’s simply that we as a culture don’t know what mathematics is. The impression we are given is of something very cold and highly technical, that no one could possibly understand- a self-fulfilling prophesy if there ever was one.

为什么我们不想让孩子们真正去“做”数学?是我们不信任他们,还是觉得数学太难了?我们似乎相信他们有能力就拿破仑的事迹进行论证并得出自己的结论,那为什么不能就三角形进行同样的思考呢?我认为,根本原因在于我们的文化不知道数学到底是什么。我们对数学的印象是冰冷、高度技术化、无人能懂的东西——这是一个彻头彻尾的自我实现的预言。

It would be bad enough if the culture were merely ignorant of mathematics, but what is far worse is that people actually think they do know what math is about- and are apparently under the gross misconception that mathematics is somehow useful to society! This is already a huge difference between mathematics and the other arts. Mathematics is viewed by the culture as some sort of tool for science and technology. Everyone knows that poetry and music are for pure enjoyment and for uplifting and ennobling the human spirit (hence their virtual elimination from the public school curriculum) but no, math is important.

如果文化只是对数学无知,那还不算太糟,但更糟糕的是,人们实际上认为自己知道数学是什么——而且显然存在一个严重的误解,认为数学在某种程度上对社会有用!这已经是数学与其他艺术形式之间的一个巨大差异。文化将数学视为科学和技术的某种工具。每个人都知道诗歌和音乐是为了纯粹的享受,是为了提升和高尚人类的精神(因此它们几乎被排除在公立学校课程之外),但数学不一样,数学很重要。

SIMPLICIO:

Are you really trying to claim that mathematics offers no useful or practical applications to society?

辛普利西奥:

你真的是在说数学对社会没有任何有用或实际的应用吗?

SALVIATI:

Of course not. I’m merely suggesting that just because something happens to have practical consequences, doesn’t mean that’s what it is about. Music can lead armies into battle, but that’s not why people write symphonies. Michelangelo decorated a ceiling, but I’m sure he had loftier things on his mind.

萨尔维亚蒂:

当然不是。我只是想说,仅仅因为某件事恰好有实际效果,并不意味着这就是它的本质目的。音乐可以激励军队奔赴战场,但这并不是人们创作交响乐的原因。米开朗基罗装饰了西斯廷教堂的天顶,但我敢肯定他心中有更崇高的追求。

SIMPLICIO:

But don’t we need people to learn those useful consequences of math? Don’t we need accountants and carpenters and such?

辛普利西奥:

但我们难道不需要人们学习数学那些有用的应用吗?我们难道不需要会计师、木匠之类的人吗?

SALVIATI:

How many people actually use any of this “practical math” they supposedly learn in school? Do you think carpenters are out there using trigonometry? How many adults remember how to divide fractions, or solve a quadratic equation? Obviously the current practical training program isn’t working, and for good reason: it is excruciatingly boring, and nobody ever uses it anyway. So why do people think it’s so important? I don’t see how it’s doing society any good to have its members walking around with vague memories of algebraic formulas and geometric diagrams, and clear memories of hating them. It might do some good, though, to show them something beautiful and give them an opportunity to enjoy being creative, flexible, open-minded thinkers- the kind of thing a real mathematical education might provide.

萨尔维亚蒂:

有多少人真的会用到他们在学校里学到的所谓“实用数学”?你觉得木匠会在工作中使用三角学吗?有多少成年人记得如何分数除法,或者解二次方程?显然,目前的实用培训项目根本不起作用,而且原因很充分:它极其无聊,而且反正没人会用。那么,为什么人们认为它如此重要?让社会成员带着对代数公式和几何图形的模糊记忆,以及对它们的强烈厌恶四处奔走,这对社会有什么好处?然而,如果能向他们展示一些美丽的东西,给他们机会享受成为有创造力、灵活、开放思维的思考者——这正是真正的数学教育所能提供的——那可能会带来一些益处。

SIMPLICIO:

But people need to be able to balance their checkbooks, don’t they?

辛普利西奥:

但人们需要会平衡支票簿,不是吗?

SALVIATI:

I’m sure most people use a calculator for everyday arithmetic. And why not? It’s certainly easier and more reliable. But my point is not just that the current system is so terribly bad, it’s that what it’s missing is so wonderfully good! Mathematics should be taught as art for art’s sake. These mundane “useful” aspects would follow naturally as a trivial by-product. Beethoven could easily write an advertising jingle, but his motivation for learning music was to create something beautiful.

萨尔维亚蒂:

我相信大多数人在日常算术时都会用计算器。为什么不用呢?这当然更简单、更可靠。但我的观点不仅仅是现行制度非常糟糕,更重要的是它缺失了极其美好的东西!数学应该作为一门为艺术而艺术的学科来教授。这些平凡的“有用”方面,自然会作为微不足道的副产品随之而来。贝多芬本可以轻松写出广告歌曲,但他学习音乐的动机是创作美丽的作品。

SIMPLICIO:

But not everyone is cut out to be an artist. What about the kids who aren’t “math people?” How would they fit into your scheme?

辛普利西奥:

但并不是每个人都适合成为艺术家。那些不是“数学型人才”的孩子怎么办?他们在你的方案中如何立足?

SALVIATI:

If everyone were exposed to mathematics in its natural state, with all the challenging fun and surprises that that entails, I think we would see a dramatic change both in the attitude of students toward mathematics, and in our conception of what it means to be “good at math.” We are losing so many potentially gifted mathematicians- creative, intelligent people who rightly reject what appears to be a meaningless and sterile subject. They are simply too smart to waste their time on such piffle.

萨尔维亚蒂:

如果每个人都能接触到数学的本来面目,体验其中蕴含的富有挑战性的乐趣和惊喜,我认为学生对数学的态度,以及我们对“擅长数学”的理解,都会发生巨大的变化。我们正在失去太多有潜力的天才数学家——那些有创造力、聪明的人,他们理所当然地拒绝了这门看似毫无意义、僵化枯燥的学科。他们太聪明了,不会把时间浪费在这种无聊的事情上。

SIMPLICIO:

But don’t you think that if math class were made more like art class that a lot of kids just wouldn’t learn anything?

辛普利西奥:

但你不觉得如果数学课变得更像美术课,很多孩子就什么都学不到了吗?

SALVIATI:

They’re not learning anything now! Better to not have math classes at all than to do what is currently being done. At least some people might have a chance to discover something beautiful on their own.

萨尔维亚蒂:

他们现在本来就什么都没学到!与其现在这样,还不如干脆不上数学课。至少有些人可能有机会自己发现一些美丽的东西。

SIMPLICIO:

So you would remove mathematics from the school curriculum?

辛普利西奥:

所以你想把数学从学校课程中移除?

SALVIATI:

The mathematics has already been removed! The only question is what to do with the vapid, hollow shell that remains. Of course I would prefer to replace it with an active and joyful engagement with mathematical ideas.

萨尔维亚蒂:

数学早就被移除了!唯一的问题是如何处理剩下的这个空洞无物的外壳。当然,我更愿意用一种积极、愉悦的方式去接触数学思想,来取代它。

SIMPLICIO:

But how many math teachers know enough about their subject to teach it that way?

辛普利西奥:

但有多少数学老师对自己的学科足够了解,能够以这种方式教学呢?

SALVIATI: Very few. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg…

萨尔维亚蒂:

非常少。而这仅仅是冰山一角……

Mathematics in School

学校中的数学

There is surely no more reliable way to kill enthusiasm and interest in a subject than to make it a mandatory part of the school curriculum. Include it as a major component of standardized testing and you virtually guarantee that the education establishment will suck the life out of it. School boards do not understand what math is, neither do educators, textbook authors, publishing companies, and sadly, neither do most of our math teachers. The scope of the problem is so enormous, I hardly know where to begin.

要扼杀学生对一门学科的热情和兴趣,最可靠的方法无疑是将其列为学校的必修课。再把它作为标准化考试的主要内容,你实际上就保证了教育机构会彻底榨干它的生命力。学校董事会不理解数学是什么,教育专家、教科书作者、出版公司也不理解,可悲的是,我们大多数数学老师也不理解。这个问题的范围如此之大,我几乎不知道从哪里开始说起。

Let’s start with the “math reform” debacle. For many years there has been a growing awareness that something is rotten in the state of mathematics education. Studies have been commissioned, conferences assembled, and countless committees of teachers, textbook publishers, and educators (whatever they are) have been formed to “fix the problem.” Quite apart from the self-serving interest paid to reform by the textbook industry (which profits from any minute political fluctuation by offering up “new” editions of their unreadable monstrosities), the entire reform movement has always missed the point. The mathematics curriculum doesn’t need to be reformed, it needs to be scrapped.

让我们从“数学改革”的惨败说起。多年来,人们越来越意识到数学教育的现状存在严重问题。研究被委托进行,会议被组织召开,无数由教师、教科书出版商和教育工作者(不管他们到底是什么身份)组成的委员会成立,旨在“解决这个问题”。姑且不论教科书行业对改革的自私利益(他们利用任何微小的政治波动,推出其晦涩难懂的“新”版本来获利),整个改革运动从一开始就偏离了重点。数学课程不需要改革,它需要被彻底废除。

All this fussing and primping about which “topics” should be taught in what order, or the use of this notation instead of that notation, or which make and model of calculator to use, for god’s sake- it’s like rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic! Mathematics is the music of reason. To do mathematics is to engage in an act of discovery and conjecture, intuition and inspiration; to be in a state of confusion- not because it makes no sense to you, but because you gave it sense and you still don’t understand what your creation is up to; to have a breakthrough idea; to be frustrated as an artist; to be awed and overwhelmed by an almost painful beauty; to be alive, damn it. Remove this from mathematics and you can have all the conferences you like; it won’t matter. Operate all you want, doctors: your patient is already dead.

所有这些关于“主题”应该按什么顺序教授、使用这种符号而不是那种符号、或者使用哪种型号的计算器的小题大做——天哪,这就像在泰坦尼克号上重新排列甲板上的椅子!数学是理性的音乐。做数学就是参与一场发现与猜想、直觉与灵感的行动;是处于一种困惑状态——不是因为它对你毫无意义,而是因为你赋予了它意义,却仍然不理解你自己的创造物在做什么;是获得突破性的想法;是像艺术家一样感到挫折;是被一种近乎令人痛苦的美所震撼和折服;是真正地活着!把这些从数学中移除,你可以召开无数次会议,但都无济于事。医生们,随便你们怎么手术:你们的病人已经死了。

The saddest part of all this “reform” are the attempts to “make math interesting” and “relevant to kids’ lives.” You don’t need to make math interesting- it’s already more interesting than we can handle! And the glory of it is its complete irrelevance to our lives. That’s why it’s so fun!

所有这些“改革”中最可悲的部分,是那些试图“让数学变得有趣”和“与孩子们的生活相关”的努力。你不需要让数学变得有趣——它本身就比我们所能承受的更有趣!而它的魅力正在于其与我们生活的完全无关性。这就是它如此有趣的原因!

Attempts to present mathematics as relevant to daily life inevitably appear forced and contrived: “You see kids, if you know algebra then you can figure out how old Maria is if we know that she is two years older than twice her age seven years ago!” (As if anyone would ever have access to that ridiculous kind of information, and not her age.) Algebra is not about daily life, it’s about numbers and symmetry- and this is a valid pursuit in and of itself:

试图将数学呈现为与日常生活相关的努力,不可避免地显得牵强附会:“孩子们,你们看,如果你懂代数,那么如果我们知道玛丽亚比她七年前年龄的两倍大两岁,你就能算出她现在多大了!”(仿佛有人会知道这种荒谬的信息,却不知道她的实际年龄。)代数与日常生活无关,它是关于数字和对称性的——而这本身就是一项有价值的追求:

Suppose I am given the sum and difference of two numbers. How can I figure out what the numbers are themselves?

假设我知道两个数的和与差,我如何才能算出这两个数本身?

Here is a simple and elegant question, and it requires no effort to be made appealing. The ancient Babylonians enjoyed working on such problems, and so do our students. (And I hope you will enjoy thinking about it too!) We don’t need to bend over backwards to give mathematics relevance. It has relevance in the same way that any art does: that of being a meaningful human experience.

这是一个简单而优雅的问题,无需费力就能吸引人。古代巴比伦人喜欢研究这类问题,我们的学生也一样。(我希望你也会喜欢思考它!)我们不需要费尽心机地让数学变得“相关”。它的相关性就像任何艺术形式一样:是一种有意义的人类体验。

In any case, do you really think kids even want something that is relevant to their daily lives? You think something practical like compound interest is going to get them excited? People enjoy fantasy, and that is just what mathematics can provide- a relief from daily life, an anodyne to the practical workaday world.

无论如何,你真的认为孩子们想要与日常生活相关的东西吗?你觉得复利这样实用的东西会让他们兴奋吗?人们喜欢幻想,而这正是数学所能提供的——一种从日常生活中解脱出来的方式,一种对务实的工作日世界的慰藉。

A similar problem occurs when teachers or textbooks succumb to “cutesyness.” This is where, in an attempt to combat so-called “math anxiety” (one of the panoply of diseases which are actually caused by school), math is made to seem “friendly.” To help your students memorize formulas for the area and circumference of a circle, for example, you might invent this whole story about “Mr. C,” who drives around “Mrs. A” and tells her how nice his “two pies are” (

C

=

2

π

r

C=2 \pi r

C=2πr ) and how her “pies are square” (

A

=

π

r

2

A=\pi r^{2}

A=πr2 ) or some such nonsense. But what about the real story? The one about mankind’s struggle with the problem of measuring curves; about Eudoxus and Archimedes and the method of exhaustion; about the transcendence of pi? Which is more interesting- measuring the rough dimensions of a circular piece of graph paper, using a formula that someone handed you without explanation (and made you memorize and practice over and over) or hearing the story of one of the most beautiful, fascinating problems, and one of the most brilliant and powerful ideas in human history? We’re killing people’s interest in circles for god’s sake!

当教师或教科书陷入“卖萌”的误区时,会出现类似的问题。为了应对所谓的“数学焦虑”(这是一系列实际上由学校造成的“疾病”之一),数学被塑造成“友好”的样子。例如,为了帮助学生记住圆的面积和周长公式,你可能会编造一个关于“C 先生”的完整故事,他开车载着“A 夫人”,告诉她他的“两个派真好吃”(

C

=

2

π

r

C=2 \pi r

C=2πr ),以及她的“派是方形的”(

A

=

π

r

2

A=\pi r^{2}

A=πr2 )之类的无稽之谈。但真正的故事是什么呢?是人类与曲线测量问题的斗争;是欧多克索斯、阿基米德和穷竭法;是圆周率的超越性?哪一个更有趣——用一个别人毫无解释就塞给你(还让你反复记忆和练习)的公式,去测量一张圆形坐标纸的大致尺寸,还是聆听人类历史上最美丽、最迷人的问题之一,以及最卓越、最强大的思想之一的故事?天哪,我们正在扼杀人们对圆的兴趣!

Why aren’t we giving our students a chance to even hear about these things, let alone giving them an opportunity to actually do some mathematics, and to come up with their own ideas, opinions, and reactions? What other subject is routinely taught without any mention of its history, philosophy, thematic development, aesthetic criteria, and current status? What other subject shuns its primary sources- beautiful works of art by some of the most creative minds in history- in favor of third-rate textbook bastardizations?

为什么我们不给学生一个机会去了解这些事情,更不用说让他们有机会真正做一些数学,提出自己的想法、观点和反应呢?还有哪门学科在教学时,通常不提及它的历史、哲学、主题发展、审美标准和现状?还有哪门学科会回避其原始资料——那些由历史上最具创造力的头脑所创造的美丽艺术作品——而偏爱三流的教科书篡改版本?

The main problem with school mathematics is that there are no problems. Oh, I know what passes for problems in math classes, these insipid “exercises.” “Here is a type of problem. Here is how to solve it. Yes it will be on the test. Do exercises 1-35 odd for homework.” What a sad way to learn mathematics: to be a trained chimpanzee.

学校数学的主要问题是“没有问题”。哦,我知道数学课上所谓的“问题”是什么——那些枯燥乏味的“练习题”。“这是一种题型,这是解题方法。这个知识点会考试。作业做 1 到 35 题的奇数题。”这是一种多么可悲的学习数学的方式:像一只训练有素的黑猩猩。

But a problem, a genuine honest-to-goodness natural human question- that’s another thing. How long is the diagonal of a cube? Do prime numbers keep going on forever? Is infinity a number? How many ways can I symmetrically tile a surface? The history of mathematics is the history of mankind’s engagement with questions like these, not the mindless regurgitation of formulas and algorithms (together with contrived exercises designed to make use of them).

但一个真正的、发自内心的、自然的人类问题——那是另一回事。立方体的对角线有多长?质数会无限延续下去吗?无穷大是一个数吗?我有多少种方法可以对称地铺砌一个平面?数学的历史就是人类探索这类问题的历史,而不是对公式和算法的机械复述(以及为了应用它们而设计的刻意练习题)。

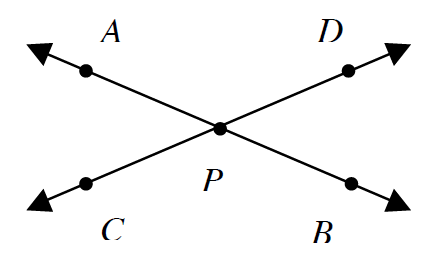

A good problem is something you don’t know how to solve. That’s what makes it a good puzzle, and a good opportunity. A good problem does not just sit there in isolation, but serves as a springboard to other interesting questions. A triangle takes up half its box. What about a pyramid inside its three-dimensional box? Can we handle this problem in a similar way?

一个好的问题是你不知道如何解决的问题。这正是它成为一个好谜题、一个好机会的原因。一个好的问题不会孤立存在,而是会成为通往其他有趣问题的跳板。三角形占据了盒子的一半空间,那么三维盒子里的金字塔呢?我们能用类似的方法解决这个问题吗?

I can understand the idea of training students to master certain techniques- I do that too. But not as an end in itself. Technique in mathematics, as in any art, should be learned in context. The great problems, their history, the creative process- that is the proper setting. Give your students a good problem, let them struggle and get frustrated. See what they come up with. Wait until they are dying for an idea, then give them some technique. But not too much.

我理解训练学生掌握特定技巧的想法——我也会这么做。但这不能作为最终目的。数学中的技巧,就像任何艺术形式中的技巧一样,应该在具体情境中学习。伟大的问题、它们的历史、创造性的过程——这才是合适的背景。给你的学生一个好问题,让他们去挣扎、去受挫。看看他们能想出什么。等到他们迫切需要一个思路时,再给他们一些技巧。但不要给太多。

So put away your lesson plans and your overhead projectors, your full-color textbook abominations, your CD-ROMs and the whole rest of the traveling circus freak show of contemporary education, and simply do mathematics with your students! Art teachers don’t waste their time with textbooks and rote training in specific techniques. They do what is natural to their subject- they get the kids painting. They go around from easel to easel, making suggestions and offering guidance:

所以,扔掉你的教案和投影仪,扔掉你那些彩色的、令人作呕的教科书,扔掉你的光盘和当代教育中所有其他华而不实的噱头, simply 和你的学生一起做数学吧!美术老师不会把时间浪费在教科书和特定技巧的死记硬背上。他们做的是与自己学科本质相符的事情——让孩子们画画。他们在画架之间来回走动,提出建议,提供指导:

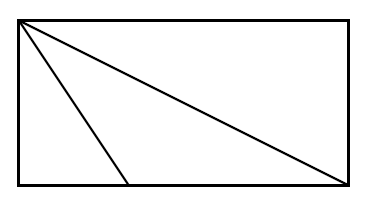

“I was thinking about our triangle problem, and I noticed something. If the triangle is really slanted then it doesn’t take up half it’s box! See, look:

“我一直在想我们的三角形问题,然后发现了一个现象。如果这个三角形非常倾斜,它就不会占据盒子的一半空间了!你看:

“Excellent observation! Our chopping argument assumes that the tip of the triangle lies directly over the base. Now we need a new idea.”

“非常棒的发现!我们之前的分割论证假设三角形的顶点正好在底边的正上方。现在我们需要一个新的思路。”

“Should I try chopping it a different way?”

“我应该尝试用不同的方式分割吗?”

“Absolutely. Try all sorts of ideas. Let me know what you come up with!”

“当然。尝试各种想法,有结果了告诉我!”

To make discoveries and formulate conjectures. By helping them to refine their arguments and creating an atmosphere of healthy and vibrant mathematical criticism. By being flexible and open to sudden changes in direction to which their curiosity may lead. In short, by having an honest intellectual relationship with our students and our subject. So how do we teach our students to do mathematics? By choosing engaging and natural problems suitable to their tastes, personalities, and level of experience. By giving them time

要让学生去发现、去提出猜想。通过帮助他们完善自己的论证,创造一种健康、活跃的数学批评氛围。通过保持灵活性,对他们的好奇心可能引领的突然方向转变持开放态度。简而言之,通过与我们的学生和我们的学科建立一种真诚的智力交流关系。那么,我们如何教学生做数学呢?通过选择适合他们兴趣、个性和经验水平的、有吸引力且自然的问题。通过给他们足够的时间。

Of course what I’m suggesting is impossible for a number of reasons. Even putting aside the fact that statewide curricula and standardized tests virtually eliminate teacher autonomy, I doubt that most teachers even want to have such an intense relationship with their students. It requires too much vulnerability and too much responsibility- in short, it’s too much work!

当然,我所建议的事情由于多种原因是不可能实现的。暂且不说全州统一的课程和标准化考试实际上剥夺了教师的自主权,我怀疑大多数教师甚至并不想与学生建立如此紧密的关系。这需要太多的投入和责任——简而言之,工作量太大了!

It is far easier to be a passive conduit of some publisher’s “materials” and to follow the shampoo-bottle instruction “lecture, test, repeat” than to think deeply and thoughtfully about the meaning of one’s subject and how best to convey that meaning directly and honestly to one’s students. We are encouraged to forego the difficult task of making decisions based on our individual wisdom and conscience, and to “get with the program.” It is simply the path of least resistance:

做一个出版商“教材”的被动传递者,遵循“讲课、考试、重复”这种洗发水式的指令,要比深入思考自己学科的意义,以及如何最好地将这种意义直接、诚实地传达给学生容易得多。我们被鼓励放弃基于个人智慧和良知做决定的艰难任务,而是“按流程办事”。这只是最省力的路径:

TEXTBOOK PUBLISHERS : TEACHERS ::

教科书出版商 : 教师 ::

A) pharmaceutical companies : doctors

A) 制药公司 : 医生

B) record companies : disk jockeys

B) 唱片公司 : 电台 DJ

C) corporations : congressmen

C) 企业 : 国会议员

D) all of the above

D) 以上皆是

The trouble is that math, like painting or poetry, is hard creative work. That makes it very difficult to teach. Mathematics is a slow, contemplative process. It takes time to produce a work of art, and it takes a skilled teacher to recognize one. Of course it’s easier to post a set of rules than to guide aspiring young artists, and it’s easier to write a VCR manual than to write an actual book with a point of view.

问题在于,数学就像绘画或诗歌一样,是艰苦的创造性工作。这使得它很难被教授。数学是一个缓慢、沉思的过程。创作一件艺术作品需要时间,而识别一件艺术作品则需要一位有技巧的教师。当然,发布一套规则比指导有抱负的年轻艺术家更容易,写一本录像机说明书也比写一本有观点的真正书籍更容易。

Mathematics is an art, and art should be taught by working artists, or if not, at least by people who appreciate the art form and can recognize it when they see it. It is not necessary that you learn music from a professional composer, but would you want yourself or your child to be taught by someone who doesn’t even play an instrument, and has never listened to a piece of music in their lives? Would you accept as an art teacher someone who has never picked up a pencil or stepped foot in a museum? Why is it that we accept math teachers who have never produced an original piece of mathematics, know nothing of the history and philosophy of the subject, nothing about recent developments, nothing in fact beyond what they are expected to present to their unfortunate students? What kind of a teacher is that? How can someone teach something that they themselves don’t do? I can’t dance, and consequently I would never presume to think that I could teach a dance class (I could try, but it wouldn’t be pretty). The difference is I know I can’t dance. I don’t have anyone telling me I’m good at dancing just because I know a bunch of dance words.

数学是一门艺术,而艺术应该由在职的艺术家来教授;如果做不到这一点,至少也应该由那些欣赏这种艺术形式、并且能识别它的人来教授。你不一定需要从专业作曲家那里学习音乐,但你会希望自己或你的孩子被一个甚至不会演奏乐器、一生中从未听过一首音乐的人教授音乐吗?你会接受一个从未拿起过画笔、从未踏入过博物馆的人作为美术老师吗?为什么我们会接受那些从未创造过任何原创数学作品、对数学的历史和哲学一无所知、对最新发展毫无了解、实际上除了要教给不幸学生的那些内容之外一无所知的数学老师?这是什么样的老师?一个人怎么能教授自己都不会做的事情?我不会跳舞,因此我绝不会冒昧地认为自己能教舞蹈课(我可以试试,但结果肯定很糟糕)。不同之处在于,我知道自己不会跳舞。不会有人因为我知道一堆舞蹈术语,就告诉我我擅长跳舞。

Now I’m not saying that math teachers need to be professional mathematicians- far from it. But shouldn’t they at least understand what mathematics is, be good at it, and enjoy doing it?

我并不是说数学老师需要是专业的数学家——远非如此。但他们至少应该理解数学是什么,擅长数学,并且喜欢做数学,难道不是吗?

If teaching is reduced to mere data transmission, if there is no sharing of excitement and wonder, if teachers themselves are passive recipients of information and not creators of new ideas, what hope is there for their students? If adding fractions is to the teacher an arbitrary set of rules, and not the outcome of a creative process and the result of aesthetic choices and desires, then of course it will feel that way to the poor students.

如果教学被简化为单纯的数据传输,如果没有对兴奋和惊奇的分享,如果教师自己只是信息的被动接收者,而不是新思想的创造者,那么他们的学生还有什么希望?如果分数加法对教师来说只是一套任意的规则,而不是创造性过程的结果,不是审美选择和渴望的产物,那么对于可怜的学生来说,它当然也会是这个样子。

Teaching is not about information. It’s about having an honest intellectual relationship with your students. It requires no method, no tools, and no training. Just the ability to be real. And if you can’t be real, then you have no right to inflict yourself upon innocent children.

教学无关乎信息传递。它关乎与你的学生建立一种真诚的智力交流关系。它不需要方法、工具或培训。只需要真诚待人的能力。如果你不能真诚待人,那么你就没有权利把自己强加给无辜的孩子。

In particular, you can’t teach teaching. Schools of education are a complete crock. Oh, you can take classes in early childhood development and whatnot, and you can be trained to use a blackboard “effectively” and to prepare an organized “lesson plan” (which, by the way, insures that your lesson will be planned, and therefore false), but you will never be a real teacher if you are unwilling to be a real person. Teaching means openness and honesty, an ability to share excitement, and a love of learning. Without these, all the education degrees in the world won’t help you, and with them they are completely unnecessary.

特别是,你无法“教授”教学本身。教育学院完全是一派胡言。哦,你可以上幼儿发展之类的课程,你可以接受培训,学习“有效”使用黑板,准备有条理的“教案”(顺便说一句,这确保了你的课是被计划好的,因此是不真实的),但如果你不愿意做一个真诚的人,你永远也成不了一名真正的教师。教学意味着开放和诚实,意味着分享兴奋的能力,意味着对学习的热爱。没有这些,世界上所有的教育学位都帮不了你;而有了这些,学位就完全没有必要了。

It’s perfectly simple. Students are not aliens. They respond to beauty and pattern, and are naturally curious like anyone else. Just talk to them! And more importantly, listen to them!

这非常简单。学生不是外星人。他们对美和模式有反应,和其他人一样天生好奇。只要和他们交流!更重要的是,倾听他们的声音!

SIMPLICIO:

All right, I understand that there is an art to mathematics and that we are not doing a good job of exposing people to it. But isn’t this a rather esoteric, highbrow sort of thing to expect from our school system? We’re not trying to create philosophers here, we just want people to have a reasonable command of basic arithmetic so they can function in society.

辛普利西奥:

好吧,我明白数学是一门艺术,而我们在让人们接触这门艺术方面做得并不好。但期望我们的学校系统提供这种深奥、高雅的东西,难道不是有点不切实际吗?我们不是要培养哲学家,我们只是想让人们掌握基本的算术,以便他们能在社会中正常生活。

SALVIATI:

But that’s not true! School mathematics concerns itself with many things that have nothing to do with the ability to get along in society- algebra and trigonometry, for instance. These studies are utterly irrelevant to daily life. I’m simply suggesting that if we are going to include such things as part of most students’ basic education, that we do it in an organic and natural way. Also, as I said before, just because a subject happens to have some mundane practical use does not mean that we have to make that use the focus of our teaching and learning. It may be true that you have to be able to read in order to fill out forms at the DMV, but that’s not why we teach children to read. We teach them to read for the higher purpose of allowing them access to beautiful and meaningful ideas. Not only would it be cruel to teach reading in such a way- to force third graders to fill out purchase orders and tax forms- it wouldn’t work! We learn things because they interest us now, not because they might be useful later. But this is exactly what we are asking children to do with math.

萨尔维亚蒂:

但这不是事实!学校数学涉及许多与社会生存能力无关的内容——比如代数和三角学。这些学习内容与日常生活完全无关。我只是建议,如果我们要将这些内容纳入大多数学生的基础教育,就应该以一种有机、自然的方式进行。此外,正如我之前所说,仅仅因为一门学科恰好有一些平凡的实际用途,并不意味着我们必须将这种用途作为教学的重点。诚然,你需要会阅读才能在车管所填写表格,但这并不是我们教孩子阅读的原因。我们教他们阅读,是为了更高层次的目的——让他们能够接触到美丽而有意义的思想。如果以那种方式教阅读——强迫三年级学生填写采购订单和纳税申报表——不仅残忍,而且行不通!我们学习东西是因为它们现在能引起我们的兴趣,而不是因为它们以后可能有用。但这正是我们要求孩子们在数学学习中做的事情。

SIMPLICIO:

But don’t we need third graders to be able to do arithmetic?

辛普利西奥:

但我们难道不需要三年级学生学会算术吗?

SALVIATI:

Why? You want to train them to calculate 427 plus 389? It’s just not a question that very many eight-year-olds are asking. For that matter, most adults don’t fully understand decimal place-value arithmetic, and you expect third graders to have a clear conception? Or do you not care if they understand it? It is simply too early for that kind of technical training. Of course it can be done, but I think it ultimately does more harm than good. Much better to wait until their own natural curiosity about numbers kicks in.

萨尔维亚蒂:

为什么?你想训练他们计算 427 加 389?这并不是很多八岁孩子会问的问题。事实上,大多数成年人都没有完全理解十进制位值算术,你却期望三年级学生有清晰的概念?或者你根本不在乎他们是否理解?进行这种技术训练还为时过早。当然,这是可以做到的,但我认为最终弊大于利。最好等到他们自己对数字产生自然的好奇心时再进行。

SIMPLICIO:

Then what should we do with young children in math class?

辛普利西奥:

那么,我们应该让小孩子在数学课上做什么呢?

SALVIATI:

Play games! Teach them Chess and Go, Hex and Backgammon, Sprouts and Nim, whatever. Make up a game. Do puzzles. Expose them to situations where deductive reasoning is necessary. Don’t worry about notation and technique, help them to become active and creative mathematical thinkers.

萨尔维亚蒂:

玩游戏!教他们国际象棋、围棋、六贯棋、双陆棋、芽苗棋、尼姆游戏,什么都行。自己编游戏,做谜题。让他们接触需要演绎推理的情境。不要担心符号和技巧,帮助他们成为积极、有创造力的数学思考者。

SIMPLICIO:

It seems like we’d be taking an awful risk. What if we de-emphasize arithmetic so much that our students end up not being able to add and subtract?

辛普利西奥:

这似乎是在冒很大的风险。如果我们如此淡化算术,以至于我们的学生最终不会加减运算,怎么办?

SALVIATI:

I think the far greater risk is that of creating schools devoid of creative expression of any kind, where the function of the students is to memorize dates, formulas, and vocabulary lists, and then regurgitate them on standardized tests-“Preparing tomorrow’s workforce today!”

萨尔维亚蒂:

我认为更大的风险是创建一所缺乏任何形式创造性表达的学校,在那里,学生的职责就是记忆日期、公式和词汇表,然后在标准化考试中复述出来——“今天为明天的劳动力做准备!”

SIMPLICIO:

But surely there is some body of mathematical facts of which an educated person should be cognizant.

辛普利西奥:

但一个受过教育的人肯定应该了解一些数学事实,不是吗?

SALVIATI:

Yes, the most important of which is that mathematics is an art form done by human beings for pleasure! Alright, yes, it would be nice if people knew a few basic things about numbers and shapes, for instance. But this will never come from rote memorization, drills, lectures, and exercises. You learn things by doing them and you remember what matters to you. We have millions of adults wandering around with “negative b plus or minus the square root of b squared minus

4

a

c

4 a c

4ac all over

2

a

2 a

2a ” in their heads, and absolutely no idea whatsoever what it means. And the reason is that they were never given the chance to discover or invent such things for themselves. They never had an engaging problem to think about, to be frustrated by, and to create in them the desire for technique or method. They were never told the history of mankind’s relationship with numbers- no ancient Babylonian problem tablets, no Rhind Papyrus, no Liber Abaci, no Ars Magna. More importantly, no chance for them to even get curious about a question; it was answered before they could ask it.

萨尔维亚蒂:

是的,其中最重要的一点是,数学是人类为了乐趣而创造的一种艺术形式!好吧,当然,如果人们能了解一些关于数字和形状的基本知识,那会很好。但这永远不会来自死记硬背、反复训练、讲座和练习。你通过实践学习东西,并且记住对你重要的东西。我们有数百万成年人,脑子里记得“负 b 加减 b 平方减

4

a

c

4 a c

4ac 的平方根,再除以

2

a

2 a

2a ”,却完全不知道这是什么意思。原因是他们从未有机会自己发现或发明这些东西。他们从未有过一个有吸引力的问题去思考、去为之受挫,并在心中产生对技巧或方法的渴望。他们从未被告知人类与数字关系的历史——没有古代巴比伦的问题泥板,没有林德纸草书,没有《计算之书》,没有《大术》。更重要的是,他们甚至没有机会对一个问题产生好奇;问题在他们提出之前就已经有了答案。

SIMPLICIO:

But we don’t have time for every student to invent mathematics for themselves! It took centuries for people to discover the Pythagorean Theorem. How can you expect the average child to do it?

辛普利西奥:

但我们没有时间让每个学生都自己发明数学!人类花了几个世纪才发现勾股定理。你怎么能期望普通孩子做到这一点呢?

SALVIATI:

I don’t. Let’s be clear about this. I’m complaining about the complete absence of art and invention, history and philosophy, context and perspective from the mathematics curriculum. That doesn’t mean that notation, technique, and the development of a knowledge base have no place. Of course they do. We should have both. If I object to a pendulum being too far to one side, it doesn’t mean I want it to be all the way on the other side. But the fact is, people learn better when the product comes out of the process. A real appreciation for poetry does not come from memorizing a bunch of poems, it comes from writing your own.

萨尔维亚蒂:

我没有这样期望。让我们把话说清楚。我抱怨的是数学课程中完全缺乏艺术与发明、历史与哲学、背景与视角。这并不意味着符号、技巧和知识体系的构建没有立足之地。当然有。我们两者都需要。如果我反对钟摆摆得太偏一边,并不意味着我希望它摆到另一边。但事实是,当成果来自过程本身时,人们学得更好。对诗歌的真正欣赏不是来自背诵一堆诗歌,而是来自自己写诗。

SIMPLICIO:

Yes, but before you can write your own poems you need to learn the alphabet. The process has to begin somewhere. You have to walk before you can run.

辛普利西奥:

是的,但在你能自己写诗之前,你需要先学习字母表。学习过程总得有个起点。你得先会走,才能跑。

SALVIATI:

No, you have to have something you want to run toward. Children can write poems and stories as they learn to read and write. A piece of writing by a six-year-old is a wonderful thing, and the spelling and punctuation errors don’t make it less so. Even very young children can invent songs, and they haven’t a clue what key it is in or what type of meter they are using.

萨尔维亚蒂:

不,你得有一个想要奔向的目标。孩子们在学习读写的过程中,就可以写诗歌和故事了。一个六岁孩子的作品是很美妙的,拼写和标点错误并不会减损它的价值。即使是非常年幼的孩子,也能创作歌曲,尽管他们完全不知道自己用的是什么调式,或者是什么节拍类型。

SIMPLICIO:

But isn’t math different? Isn’t math a language of its own, with all sorts of symbols that have to be learned before you can use it?

辛普利西奥:

但数学不一样,不是吗?数学本身就是一种语言,有各种各样的符号,你必须先学会这些符号才能使用它,不是吗?

SALVIATI:

Not at all. Mathematics is not a language, it’s an adventure. Do musicians “speak another language” simply because they choose to abbreviate their ideas with little black dots? If so, it’s no obstacle to the toddler and her song. Yes, a certain amount of mathematical shorthand has evolved over the centuries, but it is in no way essential. Most mathematics is done with a friend over a cup of coffee, with a diagram scribbled on a napkin. Mathematics is and always has been about ideas, and a valuable idea transcends the symbols with which you choose to represent it. As Gauss once remarked, “What we need are notions, not notations.”

萨尔维亚蒂:

完全不是。数学不是一种语言,而是一场冒险。难道音乐家仅仅因为用小黑点来简化记录自己的想法,就等于“说另一种语言”吗?如果是这样,这对蹒跚学步的孩子唱歌也没有阻碍。诚然,几个世纪以来,数学确实发展出了一些简化符号,但这些符号绝非必不可少。大多数数学思考,都是和朋友喝着咖啡,在餐巾纸上随手画个图完成的。数学过去是、现在也是关于思想的学科,一个有价值的思想,不会受限于你选择用来表达它的符号。正如高斯曾经说过的:“我们需要的是思想,不是符号。”

SIMPLICIO:

But isn’t one of the purposes of mathematics education to help students think in a more precise and logical way, and to develop their “quantitative reasoning skills?” Don’t all of these definitions and formulas sharpen the minds of our students?

辛普利西奥:

但数学教育的目的之一,不就是帮助学生更精确、更有逻辑地思考,培养他们的“定量推理能力”吗?难道这些定义和公式不能让学生的思维更敏锐吗?

SALVIATI:

No they don’t. If anything, the current system has the opposite effect of dulling the mind. Mental acuity of any kind comes from solving problems yourself, not from being told how to solve them.

萨尔维亚蒂:

不能。事实上,现行的教育体系反而会产生让思维变得迟钝的相反效果。任何形式的思维敏锐度,都来自于自己解决问题,而不是别人告诉你如何解决问题。

SIMPLICIO:

Fair enough. But what about those students who are interested in pursuing a career in science or engineering? Don’t they need the training that the traditional curriculum provides? Isn’t that why we teach mathematics in school?

辛普利西奥:

有道理。但那些想从事科学或工程领域职业的学生呢?他们不需要传统课程提供的训练吗?我们在学校教数学,不就是为了这个吗?

SALVIATI:

How many students taking literature classes will one day be writers? That is not why we teach literature, nor why students take it. We teach to enlighten everyone, not to train only the future professionals. In any case, the most valuable skill for a scientist or engineer is being able to think creatively and independently. The last thing anyone needs is to be trained.

萨尔维亚蒂:

有多少上文学课的学生,将来会成为作家?这既不是我们教文学的原因,也不是学生学文学的原因。我们教书是为了启发所有人,而不仅仅是培养未来的专业人士。无论如何,对科学家或工程师来说,最有价值的技能是能够创造性地独立思考。没有人需要的是“被训练”。

The Mathematics Curriculum

数学课程体系

The truly painful thing about the way mathematics is taught in school is not what is missing- the fact that there is no actual mathematics being done in our mathematics classes- but what is there in its place: the confused heap of destructive disinformation known as “the mathematics curriculum.” It is time now to take a closer look at exactly what our students are up against- what they are being exposed to in the name of mathematics, and how they are being harmed in the process.

学校教授数学的方式中,真正令人痛苦的不是缺失的部分——我们的数学课上根本没有真正的数学实践——而是取而代之的东西:那堆混乱不堪、具有破坏性的错误信息,也就是所谓的“数学课程体系”。现在,是时候仔细看看我们的学生到底面临着什么了——看看他们在“数学”的名义下接触到的是什么,以及这个过程中他们受到了怎样的伤害。

The most striking thing about this so-called mathematics curriculum is its rigidity. This is especially true in the later grades. From school to school, city to city, and state to state, the same exact things are being said and done in the same exact way and in the same exact order. Far from being disturbed and upset by this Orwellian state of affairs, most people have simply accepted this “standard model” math curriculum as being synonymous with math itself.

这个所谓的数学课程体系,最显著的特点就是它的僵化。在高年级尤其如此。无论在哪个学校、哪个城市、哪个州,教授的内容、方式和顺序都完全一样。大多数人非但没有对这种奥威尔式的现状感到不安或不满,反而简单地将这种“标准模式”的数学课程等同于数学本身。

This is intimately connected to what I call the “ladder myth”- the idea that mathematics can be arranged as a sequence of “subjects” each being in some way more advanced, or “higher” than the previous. The effect is to make school mathematics into a race- some students are “ahead” of others, and parents worry that their child is “falling behind.” And where exactly does this race lead? What is waiting at the finish line? It’s a sad race to nowhere. In the end you’ve been cheated out of a mathematical education, and you don’t even know it.

这与我所说的“阶梯神话”密切相关——这种观点认为,数学可以被安排成一系列“学科”,每个学科在某种程度上都比前一个更“高级”。其结果是,学校数学变成了一场竞赛——有些学生比其他学生“领先”,家长则担心自己的孩子“落后”。但这场竞赛到底通向哪里?终点线后有什么在等待?这是一场可悲的、没有目的地的竞赛。最终,你被剥夺了真正的数学教育,却一无所知。

Real mathematics doesn’t come in a can- there is no such thing as an Algebra II idea. Problems lead you to where they take you. Art is not a race. The ladder myth is a false image of the subject, and a teacher’s own path through the standard curriculum reinforces this myth and prevents him or her from seeing mathematics as an organic whole. As a result, we have a math curriculum with no historical perspective or thematic coherence, a fragmented collection of assorted topics and techniques, united only by the ease in which they can be reduced to step-by-step procedures.

真正的数学不是预制好的罐头——不存在“代数 II 专属思想”这种东西。问题会引导你走向它该去的地方。艺术不是竞赛。“阶梯神话”是对数学这门学科的错误描绘,而教师自己沿着标准课程体系走过的路径,又强化了这种神话,使他们无法将数学视为一个有机的整体。结果就是,我们的数学课程体系没有历史视角,也没有主题连贯性,只是一堆零散的主题和技巧的集合,唯一的共同点是它们都能轻易地被简化成一步步的流程。

In place of discovery and exploration, we have rules and regulations. We never hear a student saying, “I wanted to see if it could make any sense to raise a number to a negative power, and I found that you get a really neat pattern if you choose it to mean the reciprocal.” Instead we have teachers and textbooks presenting the “negative exponent rule” as a fait d’accompli with no mention of the aesthetics behind this choice, or even that it is a choice.

我们用规则和条例取代了发现与探索。你永远不会听到学生说:“我想知道给一个数取负指数是否有意义,然后发现如果把它定义为倒数,会得到一个非常简洁的规律。”相反,教师和教科书会把“负指数法则”当作既成事实来呈现,完全不提这个选择背后的美学考量,甚至不提这是一种“选择”。

In place of meaningful problems, which might lead to a synthesis of diverse ideas, to uncharted territories of discussion and debate, and to a feeling of thematic unity and harmony in mathematics, we have instead joyless and redundant exercises, specific to the technique under discussion, and so disconnected from each other and from mathematics as a whole that neither the students nor their teacher have the foggiest idea how or why such a thing might have come up in the first place.

我们用枯燥冗余的练习题,取代了有意义的问题——那些本可以融合不同思想、通向未知的讨论与辩论领域、让人感受到数学主题统一性与和谐性的问题。这些练习题只针对当前教授的技巧,彼此之间、与数学整体之间都毫无关联,以至于学生和教师都完全不知道,这些内容最初是如何、为何会出现的。

In place of a natural problem context in which students can make decisions about what they want their words to mean, and what notions they wish to codify, they are instead subjected to an endless sequence of unmotivated and a priori “definitions.” The curriculum is obsessed with jargon and nomenclature, seemingly for no other purpose than to provide teachers with something to test the students on. No mathematician in the world would bother making these senseless distinctions:

21

/

2

2 1/2

21/2 is a “mixed number,” while

5

/

2

5/2

5/2 is an “improper fraction.” They’re equal for crying out loud. They are the same exact numbers, and have the same exact properties. Who uses such words outside of fourth grade?

学生本可以在自然的问题情境中,决定自己的术语要表达什么意思、想要明确哪些概念,但取而代之的是,他们要面对一连串毫无缘由、先验的“定义”。课程体系对术语和命名法异常执着,似乎唯一的目的就是给教师提供考察学生的内容。世界上没有哪个数学家会费心去做这种无意义的区分:把

21

/

2

2 1/2

21/2 叫做“带分数”,把

5

/

2

5/2

5/2 叫做“假分数”。拜托,它们是相等的!它们是完全相同的数,具有完全相同的性质。除了四年级的课堂,谁会用这些词?

Of course it is far easier to test someone’s knowledge of a pointless definition than to inspire them to create something beautiful and to find their own meaning. Even if we agree that a basic common vocabulary for mathematics is valuable, this isn’t it. How sad that fifth-graders are taught to say “quadrilateral” instead of “four-sided shape,” but are never given a reason to use words like “conjecture,” and “counterexample.” High school students must learn to use the secant function, ‘

sec

x

\sec x

secx ,’ as an abbreviation for the reciprocal of the cosine function, ‘

1

/

cos

x

1 / \cos x

1/cosx ,’ (a definition with as much intellectual weight as the decision to use ‘&’ in place of “and.” ) That this particular shorthand, a holdover from fifteenth century nautical tables, is still with us (whereas others, such as the “versine” have died out) is mere historical accident, and is of utterly no value in an era when rapid and precise shipboard computation is no longer an issue. Thus we clutter our math classes with pointless nomenclature for its own sake.

当然,考察一个人对无意义定义的掌握程度,要比激励他创造美丽的事物、找到自己的意义容易得多。即使我们认同数学需要一套基本的通用术语,也绝不是现在这种。五年级学生被教说“四边形(quadrilateral)”而不是“四条边的形状(four-sided shape)”,却从未有机会使用“猜想(conjecture)”、“反例(counterexample)”这类有意义的词汇,这多么可悲。高中生必须学习正割函数‘

sec

x

\sec x

secx ’,将其作为余弦函数倒数‘

1

/

cos

x

1 / \cos x

1/cosx ’的缩写(这个定义的智力价值,和决定用‘&’代替“and”没什么区别)。这种特定的简化符号是15世纪航海表格的遗留物,如今仍在使用(而正矢函数“versine”等其他符号已被淘汰),这纯粹是历史偶然;在船舶不再需要快速精确计算的时代,它已经毫无价值。就这样,我们的数学课被这些无意义的术语填满了。

In practice, the curriculum is not even so much a sequence of topics, or ideas, as it is a sequence of notations. Apparently mathematics consists of a secret list of mystical symbols and rules for their manipulation. Young children are given ‘

+

+

+ ’ and ‘

÷

\div

÷ .’ Only later can they be entrusted with ‘

\sqrt{}

,’ and then ‘

x

x

x ’ and ‘

y

y

y ’ and the alchemy of parentheses. Finally, they are indoctrinated in the use of ‘

sin

\sin

sin ,’ ‘

log

\log

log ,’ ‘

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) ,’ and if they are deemed worthy, ‘

d

d

d ’ and ‘

∫

\int

∫ .’ All without having had a single meaningful mathematical experience.

实际上,这个课程体系与其说是一系列主题或思想的集合,不如说是一系列符号的排列。显然,在这种体系里,数学就是一份包含神秘符号和操作规则的秘密清单。小孩子先接触‘

+

+

+ ’和‘

÷

\div

÷ ’;后来才能接触‘

\sqrt{}

’;再之后是‘

x

x

x ’、‘

y

y

y ’和括号的“魔法”;最后,如果他们被认为“够格”,会被灌输‘

sin

\sin

sin ’、‘

log

\log

log ’、‘

f

(

x

)

f(x)

f(x) ’的用法,甚至‘

d

d

d ’和‘

∫

\int

∫ ’。而这一切,都是在他们没有任何一次有意义的数学体验的情况下发生的。

This program is so firmly fixed in place that teachers and textbook authors can reliably predict, years in advance, exactly what students will be doing, down to the very page of exercises. It is not at all uncommon to find second-year algebra students being asked to calculate

[

f

(

x

+

h

)

−

f

(

x

)

]

/

h

[f(x+h)-f(x)] / h

[f(x+h)−f(x)]/h for various functions

f

f

f , so that they will have “seen” this when they take calculus a few years later. Naturally no motivation is given (nor expected) for why such a seemingly random combination of operations would be of interest, although I’m sure there are many teachers who try to explain what such a thing might mean, and think they are doing their students a favor, when in fact to them it is just one more boring math problem to be gotten over with. “What do they want me to do? Oh, just plug it in? OK.”

这个课程体系固定得如此牢固,以至于教师和教科书作者能提前好几年准确预测学生要学什么,甚至精确到练习题的页码。代数二年级的学生被要求计算不同函数

f

f

f 的

[

f

(

x

+

h

)

−

f

(

x

)

]

/

h

[f(x+h)-f(x)] / h

[f(x+h)−f(x)]/h ,美其名曰让他们在几年后学微积分时“有印象”,这种情况非常普遍。当然,没有人会解释(也没人期待解释)为什么这种看似随机的运算组合会有意义——尽管我相信很多教师会试图解释它的含义,并认为这是在帮学生,但实际上,对学生来说,这只是又一道需要应付的无聊数学题。“他们想让我做什么?哦,只是代入计算?行吧。”

Another example is the training of students to express information in an unnecessarily complicated form, merely because at some distant future period it will have meaning. Does any middle school algebra teacher have the slightest clue why he is asking his students to rephrase “the number

x

x

x lies between three and seven” as

∣

x

−

5

∣

<

2

|x-5|<2

∣x−5∣<2 ? Do these hopelessly inept textbook authors really believe they are helping students by preparing them for a possible day, years hence, when they might be operating within the context of a higher-dimensional geometry or an abstract metric space? I doubt it. I expect they are simply copying each other decade after decade, maybe changing the fonts or the highlight colors, and beaming with pride when a school system adopts their book, and becomes their unwitting accomplice.

另一个例子是,训练学生用不必要的复杂形式表达信息,仅仅因为在遥远的未来,这种形式可能会有意义。有哪个初中代数老师清楚,为什么要让学生把“数

x

x

x 在 3 和 7 之间”重新表述成

∣

x

−

5

∣

<

2

|x-5|<2

∣x−5∣<2 ?这些极其无能的教科书作者,真的认为让学生为多年后可能接触的高维几何或抽象度量空间做准备,是在帮助他们吗?我对此表示怀疑。我猜他们只是在十年又十年地互相抄袭,或许改改字体或高亮颜色,然后在某个学校系统采用他们的书、无意中成为他们的帮凶时,便沾沾自喜。

Mathematics is about problems, and problems must be made the focus of a student’s mathematical life. Painful and creatively frustrating as it may be, students and their teachers should at all times be engaged in the process- having ideas, not having ideas, discovering patterns, making conjectures, constructing examples and counterexamples, devising arguments, and critiquing each other’s work. Specific techniques and methods will arise naturally out of this process, as they did historically: not isolated from, but organically connected to, and as an outgrowth of, their problem-background.

数学是关于问题的,问题必须成为学生数学学习的核心。尽管这个过程可能充满痛苦和创造性挫折,但学生和教师都应该始终投入其中——产生想法、毫无头绪、发现规律、提出猜想、构建例子与反例、设计论证、批判彼此的工作。特定的技巧和方法会从这个过程中自然产生,就像它们在历史上那样:不是孤立存在的,而是与问题背景有机相连、作为其产物而出现的。

English teachers know that spelling and pronunciation are best learned in a context of reading and writing. History teachers know that names and dates are uninteresting when removed from the unfolding backstory of events. Why does mathematics education remain stuck in the nineteenth century? Compare your own experience of learning algebra with Bertrand Russell’s recollection:

英语教师知道,拼写和发音在读写语境中学习效果最好。历史教师知道,脱离事件发展的背景故事,人名和日期会变得毫无趣味。为什么数学教育还停留在19世纪?把你自己学习代数的经历,和伯特兰·罗素的回忆对比一下:

“I was made to learn by heart: ‘The square of the sum of two numbers is equal to the sum of their squares increased by twice their product.’ I had not the vaguest idea what this meant and when I could not remember the words, my tutor threw the book at my head, which did not stimulate my intellect in any way.”

“我被迫背诵:‘两个数的和的平方,等于它们的平方和加上它们乘积的两倍。’我完全不知道这是什么意思,当我记不住这句话时,我的导师就把书扔到我头上,这对我的智力毫无启发。”

Are things really any different today?

如今的情况真的有任何不同吗?

SIMPLICIO: I don’t think that’s very fair. Surely teaching methods have improved since then.

辛普利西奥:我觉得这不太公平。从那以后,教学方法肯定已经改进了。

SALVIATI:

You mean training methods. Teaching is a messy human relationship; it does not require a method. Or rather I should say, if you need a method you’re probably not a very good teacher. If you don’t have enough of a feeling for your subject to be able to talk about it in your own voice, in a natural and spontaneous way, how well could you understand it? And speaking of being stuck in the nineteenth century, isn’t it shocking how the curriculum itself is stuck in the seventeenth? To think of all the amazing discoveries and profound revolutions in mathematical thought that have occurred in the last three centuries! There is no more mention of these than if they had never happened.

萨尔维亚蒂:

你说的是“训练方法”。教学是一种复杂的人际互动,不需要什么“方法”。或者更准确地说,如果你需要靠“方法”教学,那你可能不是一个好老师。如果你对你的学科没有足够的感悟,无法用自己的声音、自然自发地谈论它,那你对它的理解能有多深?说到停留在19世纪,课程体系本身停留在17世纪,难道不更令人震惊吗?想想过去三个世纪里,数学思想领域出现了多少惊人的发现和深刻的变革!但课程体系对这些内容的提及,就好像它们从未发生过一样。

SIMPLICIO:

But aren’t you asking an awful lot from our math teachers? You expect them to provide individual attention to dozens of students, guiding them on their own paths toward discovery and enlightenment, and to be up on recent mathematical history as well?

辛普利西奥:

但你对我们的数学教师要求是不是太高了?你期望他们给几十个学生提供个性化关注,引导他们沿着各自的路径去发现和领悟,同时还要了解最新的数学史?

SALVIATI:

Do you expect your art teacher to be able to give you individualized, knowledgeable advice about your painting? Do you expect her to know anything about the last three hundred years of art history? But seriously, I don’t expect anything of the kind, I only wish it were so.

萨尔维亚蒂:

你难道不期望你的美术老师能就你的画作,给出个性化、有见识的建议吗?你不期望她了解过去三百年的艺术史吗?但说真的,我并没有期望数学教师能做到这些,我只是希望情况能如此。

SIMPLICIO:

So you blame the math teachers?

辛普利西奥:

所以你在责怪数学教师?

SALVIATI:

No, I blame the culture that produces them. The poor devils are trying their best, and are only doing what they’ve been trained to do. I’m sure most of them love their students and hate what they are being forced to put them through. They know in their hearts that it is meaningless and degrading. They can sense that they have been made cogs in a great soul-crushing machine, but they lack the perspective needed to understand it, or to fight against it. They only know they have to get the students “ready for next year.”

萨尔维亚蒂:

不,我责怪的是培养他们的文化。这些可怜的人已经在尽最大努力了,他们只是在做自己被训练去做的事。我相信他们大多数人都爱自己的学生,也痛恨自己被迫让学生经历这些。他们内心深处知道这一切是无意义且有辱人格的。他们能感觉到自己成了一台摧残心灵的巨大机器上的齿轮,却缺乏理解或反抗这台机器所需的视角。他们只知道,必须让学生“为明年做好准备”。

SIMPLICIO:

Do you really think that most students are capable of operating on such a high level as to create their own mathematics?

辛普利西奥:

你真的认为大多数学生都能达到自己创造数学的高水平吗?

SALVIATI:

If we honestly believe that creative reasoning is too “high” for our students, and that they can’t handle it, why do we allow them to write history papers or essays about Shakespeare? The problem is not that the students can’t handle it, it’s that none of the teachers can. They’ve never proved anything themselves, so how could they possibly advise a student? In any case, there would obviously be a range of student interest and ability, as there is in any subject, but at least students would like or dislike mathematics for what it really is, and not for this perverse mockery of it.

萨尔维亚蒂:

如果我们真的认为创造性推理对学生来说太“高深”,他们无法应对,那为什么我们允许他们写历史论文或关于莎士比亚的文章呢?问题不在于学生无法应对,而在于教师们都做不到。他们自己从未证明过任何东西,怎么可能给学生提供建议?无论如何,和任何学科一样,学生的兴趣和能力显然会有差异,但至少学生喜欢或讨厌数学,是因为数学本身,而不是因为这种对数学的扭曲模仿。

SIMPLICIO:

But surely we want all of our students to learn a basic set of facts and skills. That’s what a curriculum is for, and that’s why it is so uniform- there are certain timeless, cold hard facts we need our students to know: one plus one is two, and the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees. These are not opinions, or mushy artistic feelings.

辛普利西奥:

但我们肯定希望所有学生都学到一套基本的事实和技能。这就是课程体系的目的,也是它如此统一的原因——有些永恒、确凿的事实,我们需要学生了解:1加1等于2,三角形的内角和是180度。这些不是观点,也不是模糊的艺术感受。

SALVIATI:

On the contrary. Mathematical structures, useful or not, are invented and developed within a problem context, and derive their meaning from that context. Sometimes we want one plus one to equal zero (as in so-called ‘mod 2’ arithmetic) and on the surface of a sphere the angles of a triangle add up to more than 180 degrees. There are no “facts” per se; everything is relative and relational. It is the story that matters, not just the ending.

萨尔维亚蒂:

恰恰相反。无论是否有用,数学结构都是在问题情境中被发明和发展的,其意义也源于这个情境。有时候,我们会让1加1等于0(比如在所谓的“模2算术”中);而在球面上,三角形的内角和会大于180度。根本不存在所谓的“绝对事实”,一切都是相对的、相关的。重要的是过程和背景,而不仅仅是结果。

SIMPLICIO:

I’m getting tired of all your mystical mumbo-jumbo! Basic arithmetic, all right? Do you or do you not agree that students should learn it?

辛普利西奥:

我已经听腻了你这些神秘的胡言乱语!就说基础算术,好吗?你到底同不同意学生应该学基础算术?

SALVIATI:

That depends on what you mean by “it.” If you mean having an appreciation for the problems of counting and arranging, the advantages of grouping and naming, the distinction between a representation and the thing itself, and some idea of the historical development of number systems, then yes, I do think our students should be exposed to such things. If you mean the rote memorization of arithmetic facts without any underlying conceptual framework, then no. If you mean exploring the not at all obvious fact that five groups of seven is the same as seven groups of five, then yes. If you mean making a rule that

5

×

7

=

7

×

5

5 ×7=7 ×5

5×7=7×5 , then no. Doing mathematics should always mean discovering patterns and crafting beautiful and meaningful explanations.

萨尔维亚蒂:

这取决于你说的“基础算术”是什么意思。如果你指的是理解计数和排列的问题、分组和命名的优势、符号与事物本身的区别,以及对数字系统历史发展的一些了解,那么是的,我认为学生应该接触这些内容。如果你指的是在没有任何底层概念框架的情况下,死记硬背算术事实,那么不。如果你指的是探索“5个7相加”和“7个5相加”相等这个并非显而易见的事实,那么是的。如果你指的是制定一条“

5

×

7

=

7

×

5

5 ×7=7 ×5

5×7=7×5 ”的规则,那么不。做数学,永远应该意味着发现规律,并构建优美且有意义的解释。

SIMPLICIO:

What about geometry? Don’t students prove things there? Isn’t High School Geometry a perfect example of what you want math classes to be?

辛普利西奥:

那几何呢?学生不是在几何课上证明东西吗?高中几何难道不是你理想中数学课的完美例子吗?

High School Geometry: Instrument of the Devil

高中几何:魔鬼的工具

There is nothing quite so vexing to the author of a scathing indictment as having the primary target of his venom offered up in his support. And never was a wolf in sheep’s clothing as insidious, nor a false friend as treacherous, as High School Geometry. It is precisely because it is school’s attempt to introduce students to the art of argument that makes it so very dangerous.

对于一篇尖锐控诉文的作者来说,最令人恼火的莫过于自己主要抨击的对象,反而被当作支持自己观点的例子。而高中几何,就是这样一只披着羊皮、阴险狡诈的狼,一个背信弃义的假朋友。正是因为它试图向学生介绍论证的艺术,才使得它如此危险。

Posing as the arena in which students will finally get to engage in true mathematical reasoning, this virus attacks mathematics at its heart, destroying the very essence of creative rational argument, poisoning the students’ enjoyment of this fascinating and beautiful subject, and permanently disabling them from thinking about math in a natural and intuitive way.

它伪装成一个让学生终于能进行真正数学推理的舞台,却像病毒一样攻击数学的核心,摧毁创造性理性论证的本质,扼杀学生对这门迷人而美丽学科的热爱,并永久地让他们无法以自然、直观的方式思考数学。

The mechanism behind this is subtle and devious. The student-victim is first stunned and paralyzed by an onslaught of pointless definitions, propositions, and notations, and is then slowly and painstakingly weaned away from any natural curiosity or intuition about shapes and their patterns by a systematic indoctrination into the stilted language and artificial format of so-called “formal geometric proof.”

这背后的机制微妙而阴险。受害的学生首先被大量无意义的定义、命题和符号冲击得不知所措,然后通过系统灌输所谓“正式几何证明”的生硬语言和人为格式,逐渐、痛苦地失去对形状及其规律的自然好奇心和直觉。

All metaphor aside, geometry class is by far the most mentally and emotionally destructive component of the entire K-12 mathematics curriculum. Other math courses may hide the beautiful bird, or put it in a cage, but in geometry class it is openly and cruelly tortured. (Apparently I am incapable of putting all metaphor aside.)

抛开所有比喻不谈,几何课是整个K-12数学课程体系中,对学生心智和情感最具破坏性的部分。其他数学课程可能只是把美丽的鸟儿藏起来,或者关进笼子,但在几何课上,这只鸟被公然、残忍地折磨。(显然,我还是忍不住要用比喻。)

What is happening is the systematic undermining of the student’s intuition. A proof, that is, a mathematical argument, is a work of fiction, a poem. Its goal is to satisfy. A beautiful proof should explain, and it should explain clearly, deeply, and elegantly. A well-written, well-crafted argument should feel like a splash of cool water, and be a beacon of light— it should refresh the spirit and illuminate the mind. And it should be charming.

实际发生的事情,是对学生直觉的系统性破坏。证明,也就是数学论证,是一部虚构作品,一首诗。它的目标是让人信服。一个优美的证明应该能解释问题,而且解释得清晰、深刻、优雅。一篇写得好、构思精妙的论证,应该像一阵清凉的水花,像一盏明灯——它能振奋精神,启迪心灵,而且应该富有魅力。

There is nothing charming about what passes for proof in geometry class. Students are presented a rigid and dogmatic format in which their so-called “proofs” are to be conducted— a format as unnecessary and inappropriate as insisting that children who wish to plant a garden refer to their flowers by genus and species.

几何课上所谓的“证明”,毫无魅力可言。学生们被要求用一种僵化、教条的格式来完成他们的“证明”——这种格式的不必要和不合时宜,就好比强迫想种花的孩子用属名和种名来称呼他们的花。

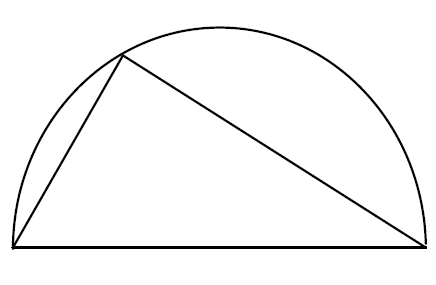

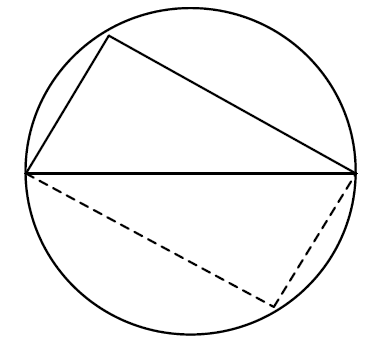

Let’s look at some specific instances of this insanity. We’ll begin with the example of two crossed lines:

让我们看看这种荒谬的具体例子。先从两条相交的直线说起: