递归的定义:程序调用自身的编程技巧称为递归。

递归的两个必要的条件:

1.存在限制条件,当满足这个限制条件的时候,递归便不再继续。

2.每次递归调用之后会越来越接近这个限制条件。

我们以一个代码为例:

输入任意数字,分别打印该数字的每一位。

#include <stdio.h>

int print(int n)

{

if (n > 9)

{

print(n/10);

}

printf("%d\n", n % 10);

}

int main()

{

int num = 0;

scanf("%d", &num);

print(num);

return 0;

}

这段代码中,假设我们输入一个三位数368,那么先打印36和8,然后再次将36调入,打印出3和6。

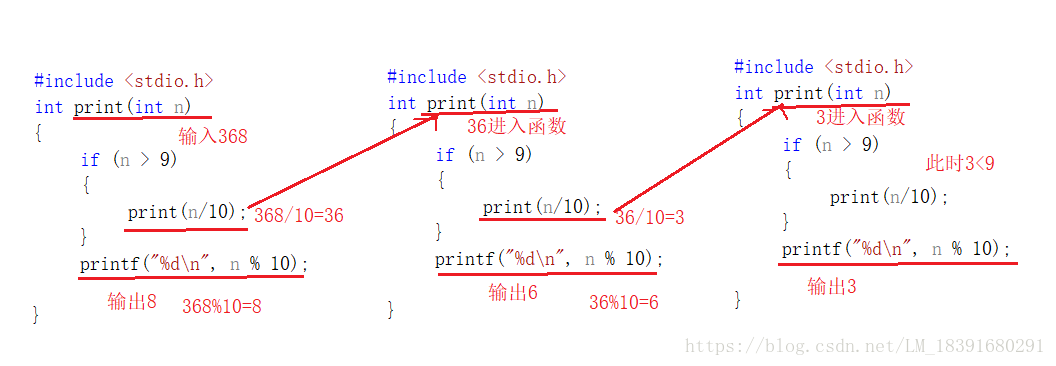

我们用一张图来表达一下这个过程

函数通过多次调用自身,达到单独打印出一个数字每一位的效果。

接下来,我们继续以一些实例来运用递归

不创建临时变量,求字符串的长度(strlen递归写法)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <assert.h>

int my_strlen(const char* str)

{

assert(str != NULL);

if (*str != '\0')

{

return 1 + my_strlen(str + 1);

}

else

{

return 0;

}

}

int main()

{

char *p = "abc";

int len = my_strlen(p);

printf("%d\n", len);

return 0;

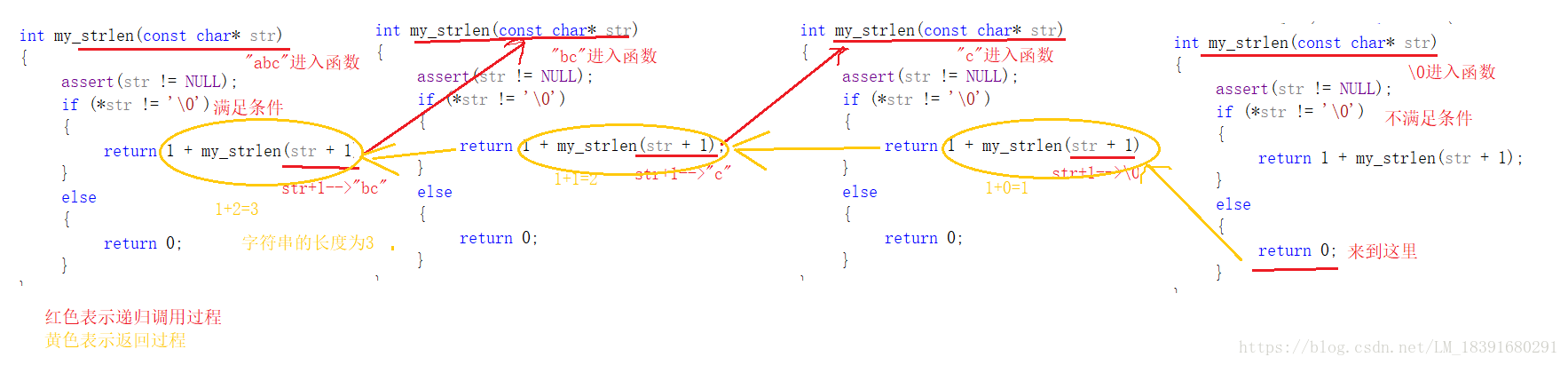

}过程如图:

既然已经说到求字符串长度的问题,那么我们在拓展一下另一种strlen常规写法

#include <stdio.h>

#include <assert.h>

int my_strlen(const char* str)//因为My_strlrn只是求字符串的长度,并不改变它,加上const对他进行简单的保护

{

int count = 0;//定义一个计数器来计算字符串的长度

assert(str != NULL);//str 有可能为空指针,但我们不容许它为空,这里使用断言来限制它不为空

while (*str != '\0')

{//字符串不为零就持续向后计数

count++;

str++;

}

return count;;

}

int main()

{

char *p = "abcdef";

int len = my_strlen(p);

printf("%d\n", len);

return 0;

}递归方法求第n个斐波那契数

#include <stdio.h>

int fib(int n)

{

if (n <= 2)

{

return 1;

}

else

{

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

}

int main()

{

int num = 9;

fib(num);

printf("%d\n", fib(num));

}非递归的方法这样写

#include <stdio.h>

int fib(int n)

{

int a = 1;

int b = 1;

int c = a;

while (n > 2)

{

c = a + b;

a = b;

b = c;

n--;

}

return c;

}

int main()

{

int n = 5;

printf("%d\n", fib(n));

return 0;

}递归求n的阶乘

#include <stdio.h>

int fac(int n)

{

if (n <= 1)

{

return 1;

}

else

{

return n*fac(n - 1);

}

}

int main()

{

int num = 5;

fac(num);

printf("%d\n", fac(num));

}我们在使用递归来计算一个比较大的斐波那切数的时候(均不考虑栈溢出),程序会特别的慢;在用递归计算很大的数时,程序会崩溃。其实是因为函数在频繁调用的过程中,很多计算一直重复,就会导致程序的效率降低。

系统分配给程序的栈空间是有限的,当出现死循环,或者不断的递归,一直开辟栈空间,最终导致栈空间耗尽,这样的现象我们叫做栈溢出

.

1379

1379

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?